On top of 63 million missing women, a new report from the Indian government reveals an even more pervasive pattern of sexism in recent demographic data—hinting at persistent patriarchal preferences impervious to India's economic boom.

Will the rising tide of India's rapid economic development lift all Indians equally, and gradually wash away gender discrimination and patriarchy? That's the question—and clearly the hope—underlying chapter seven of India's 2018 Economic Survey, led by the Chief Economic Advisor Arvind Subramanian (on leave from CGD) and released by the Ministry of Finance on Monday.

Building on Seema Jayachandran's recent review from a global perspective, the Economic Survey finds that on 12 out of 17 indicators measuring women's welfare and agency, India has progressed over the most recent decade for which data are available (2005-6 to 2015-6), and in most of those progress has been roughly at the pace its economic growth would predict.

But there are glaring exceptions. Notably, Indian women have depressingly little agency in their reproductive choices. Sterilization, as opposed to other reversible forms of birth control, is 50 percent more common in India than income would predict, and barely declining overtime. On the purely economic front, women's employment in non-manual work has risen over the last decade, but India remains a (bad) outlier for its level of GDP.

Underlying these failings, the report's diagnosis focuses on stubborn cultural norms: son preference, and the ugly term, "son meta-preference."

How meta-preferences produce "unwanted girls"

Son preference manifests itself in sex-selective abortions and differential treatment of boys and girls. It produces the startling imbalance in gender ratios in India, known as "missing women" in Amartya Sen's famous phrasing. The Economic Survey places the current tally of missing women at 63 million.

But as the report points out, the reality is worse than this. Even where sex ratios are balanced, son preference may be widespread. Couples' decisions to keep having kids until they get a boy—what scholars refer to as “son meta-preference”—create what the report calls "unwanted girls." This neologism refers to a phenomenon that is visible only in the sex ratio imbalances of the last child among women who have completed fertility.

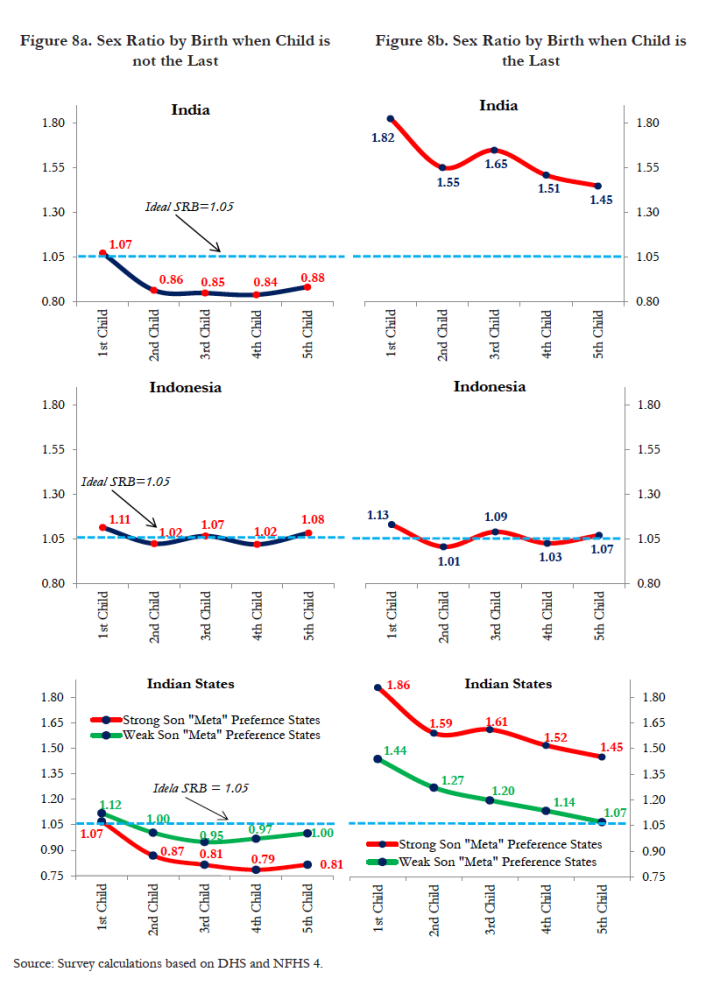

Our chart of the week, pictured above, shows this phenomenon of son meta-preference in stark relief:

For India, the sex ratio of the last child for first-borns is 1.82, heavily skewed in favor of boys compared with the ideal sex ratio of 1.05. This ratio drops to 1.55 for the second child for families that have exactly two children and so on. The striking contrast between the two panels conveys a sense of son meta preference. This contrast is even more stark when seen against the performance of Indonesia (middle panels) where the SRLC is close to the ideal, regardless of the birth order and whether the child is the last or not.

Adding up the gap between the ideal sex ratio of 1.05 and the actual ratio for the last child, the Economic Survey calculates there are 21 million "unwanted girls" among females ages 0-25 in India today.

Without making any strong claims of causation, it is notable that "unwanted girls" are concentrated in Indian states where as adult women they are likely to experience low welfare outcomes and limited agency (see the bottom panel of the figure above). As Seema Jayachandran and Rohini Pande show in their recent article in the American Economic Review, these kinds of preferences can help explain the much higher incidence of malnutrition among Indian children relative to their peers in most African countries.

So is growth alone enough?

The obvious answer is no. America, for instance, is rich, yet women earn only 80 percent of the wages of men, and one in six women report being raped. And families of Indian origin living in Canada still report sex ratio imbalances.

In an extremely thoughtful review of the literature on the reciprocal relationship between economic development and women's economic empowerment, MIT economist Esther Duflo concludes that while causation surely flows in both directions, the relationships are often weaker than we might hope. Her final verdict is that "economic development alone will probably not be enough to bring about equality between women and men in the foreseeable future, and policies will be required to accelerate this process."

The Economic Survey is a bit weak on this last point, listing a handful of government efforts to promote gender equality, without any data on their success. Lest anyone be confused, the Survey's demonstration of deep social norms and preferences underlying India's unequal gender outcomes is no justification for policy quietism—nor is it presented as such. Preferences can be changed, and even when they can't, people with patriarchal preferences still respond to incentives. It's up to policymakers to start providing better ones.

Thanks to Divyanshi Wadhwa for research assistance.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.