Recommended

With all the attention to impact investment and blended finance in Davos last week, development impact bonds (DIBs) should be center stage. In 2013, CGD’s own working group on DIBs highlighted the important benefits of these innovative financing models, and worked through some of the “how-to” of their design and implementation.

Yet five years later, only three development impact bonds have launched (see Brookings’ nice summary here). Why is this the case? Why is it so hard to get DIBs off the ground? What can we learn from the structuring and financing of DIBs to date to ease the way for future efforts?

To learn more, CGD will host the coalition that recently finalized a DIB to reduce preventable blindness from cataracts in Cameroon and neighboring countries. Cataracts cause about half the world’s blindness; a 20-minute surgical repair can save a life-year for US$ 13-17 in a typical country in sub-Saharan Africa. And there is evidence of demand and willingness to pay, even in very poor countries, given the huge economic impact that blindness can have on a family’s income and labor. The very poorest still require subsidy, but while people wait around for more comprehensive health coverage from governments, a private sector offer is likely to be highly demanded.

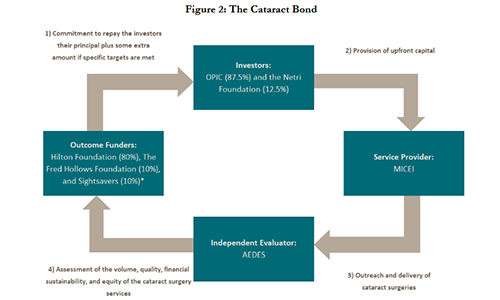

The DIB is centered around a for-profit service provider—the newly built Magrabi ICO Cameroon Eye Institute (MICEI). MICEI is implementing a model of eye care first popularized in India by the Aravind Eye Care System, and better known to many as a “bottom of the pyramid” private sector initiative—delivering “low price, low margin, high volume” cataract surgeries with big reductions in blindness. The DIB’s structure is shown in the figure below.

This DIB is relatively small in financial terms—$2 million—and the upfront costs associated with preparing the DIB have been significant (~800k). The main hurdle for this DIB was not identifying an outcome funder, but instead, finding the private investors to make the upfront commitments to the project. In the final iteration of the term sheet, the returns for private investors are excellent—8 percent interest if targets are met versus 4 percent if they are not met, and 100 percent of the principal is repaid by the outcome funders if the targets are not met, though the timing of the repayment is extended. This is quite different from the riskier terms that were proposed in CGD’s earlier work on DIBs.

What’s going on? Based on interviews and input from coalition members and lessons from elsewhere, our new paper with Lachlan MacDonald sets out some initial thoughts. Among these, there are two underlying features that have affected investor appetite for the DIB, and that may well be affecting many of the DIB proposals under preparation.

First, the absence of a performance and revenues track record for MICEI meant that there was little data on which to form a confident assessment of future performance and therefore the financial risks facing any investor (though data from other hospitals run by MICEI’s parent organization exist). The intervention—cataract surgery using the Aravind model—is well-established, but how was anyone to know whether it could be done at a reasonable price and within the expected timeframe in Cameroon specifically? This is a quite common starting point for DIBs, and it suggests that the market might be more attractive if systematic efforts were made to generate better data on service delivery and costs in the private sector.

Second, prospective investors lacked much familiarity with the country, the sector, and the service provider(s). The Cameroon bond handled this primarily through the stellar reputations of its partner organizations and, in retrospect, some of the partners felt that these reputational assurances could have been marketed to potential investors more aggressively.

The DIB has many good features—it is leveraging upfront money alongside, hopefully, some private sector discipline on performance. Its evaluation metrics are much stronger than those seen in standard IFC loans; the DIB measures and rewards the number and outcomes of cataract surgery and adds a bonus for equity in provision, while previous IFC loans have reported on numbers of patients reached. The DIB is also bringing in some new funders to an important and underserved area of global health. But the experience has also signaled that there is much work to do to ready health providers for private investment, and to familiarize and negotiate strategically with prospective investors.

RSVP to attend the event here to learn about the Coalition’s experience and insights.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.