Since 2008, programs for Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation Plus (REDD+) have pioneered the use of performance payments to reduce tropical deforestation. While these programs generated hopes of slowing climate change and protecting indigenous peoples’ access to their lands, they also generated fears over misuse of funds, abuses of rights, displacement and commodification of the environment.

In response, international forest agreements have been “aidified”—moving away from their initial “hands-off” approach and adopting detailed implementation plans and preparatory phases. This shift has had consequences for the pace of implementation, for slowing deforestation, and for the status of indigenous peoples living in and near these forests.

A new CGD working paper—“Guyana’s REDD+ Agreement with Norway: Perceptions of and Impacts on Indigenous Communities”—describes how this process unfolded in Guyana. In this case, it seems that neither hopes nor fears were fully realized. But the consequences are still significant, as the imperatives of preserving the forest and securing indigenous rights have entered the country’s political discourse and survived a significant change in government.

The agreement

In 2009, when Norway and Guyana signed a $250 million agreement to preserve tropical forests, the two governments envisioned a financial mechanism that would rapidly channel resources into this nation of 770,000 people—with a forest the size of England—to support low-carbon economic development and preempt pressures that might otherwise lead to deforestation. Adding urgency to this initiative, a government report based on analysis by McKinsey consultants warned that deforestation could rise from less than 0.3% to over 4% annually due to agricultural expansion.

The conditions

The Guyana-Norway agreement was promoted as another “hands-off” agreement, similar to Norway’s previous agreement with Brazil. It established a contribution of $5 per ton of greenhouse gas emissions averted for keeping deforestation below a historical rate—in this case a target of less than 0.275% of Guyana’s standing forests. But in practical terms, the agreement was increasingly “hands-on.” In particular, Guyana had to establish a strategic framework, engage in a national consultation process, improve governance, and channel funds through an intermediary—the World Bank— which added further conditions for disbursements.

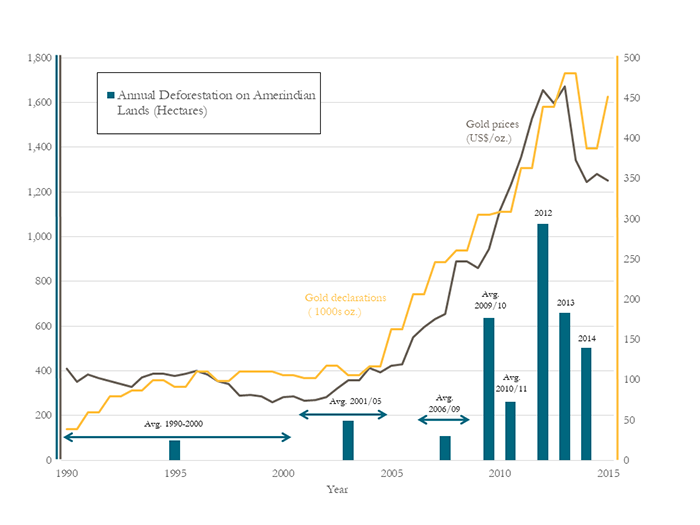

The consequence of this “hands-on” design was to slow implementation and limit adaptability. Norway had disbursed about $125 million in performance payments by 2016, but much of this money was held for investment in the Amaila Hydropower project (which was subsequently cancelled) and most of the rest was held up in the Guyana REDD+ Investment Fund (GRIF). The GRIF is administered by the World Bank, which focused its attention on compliance rather than technical support. As for adaptability, in retrospect, the biggest problem was the program’s failure to anticipate and address the threat posed by gold mining (see Figure 1).

We cannot know if a more “hands-off” REDD+ program would have worked better. It might have been more agile, spending less time on compliance with procedure and more attention on the actual trends which required timely action. However, it could also have stalled if the government failed to exploit this flexibility effectively.

Deforestation on Amerindian Lands, Gold Production, and Gold Prices (1995-2015)

Source: Guyana Forestry Commission (2015); Kitco; and Guyana Geology and Mines Commission

Few harms—or benefits—for Indigenous peoples

Given the slow pace of implementation, it is not surprising that the main fears voiced by indigenous groups have not materialized, nor have their hopes. The Government’s new national strategy did not lead to land seizures or threaten traditional cultivation practices. But it also did not generate many benefits. For example, under the Amerindian Land Titling Project, only 15 certificates of title were issued to Amerindian villages—well below the program’s original goal of 68. The national consultation process was unprecedented, involving 0.5% of the population, but was short-lived and criticized as “one-way.” A key element of the national strategy, the Amaila Falls hydropower project, was ultimately cancelled, eliminating jobs and financing that were supposed to benefit indigenous communities, but also relieving a significant pressure on the forest. At this stage, Amerindian groups seem to have lost interest in REDD+, with leaders skeptical that anything will materialize.

Forest protection and indigenous rights on the agenda

The author of the paper, Tim Laing, argues that the main consequence of the REDD+ agreement in Guyana may have been to secure a place in the national debate for climate change, forest protection, and indigenous rights. The national low-carbon development strategy launched in 2009 was closely associated with President Bharrat Jagdeo, who negotiated and signed the REDD+ agreement. The consultation process was criticized in particular for not engaging opposition members in Parliament. Yet, the government elected in 2015 (and led by parties that were in opposition to Jagdeo) has preserved the main elements of the low-carbon approach in its Green State Development Strategy. Smaller-scale forest conservation projects and efforts to address mining are also underway, but ultimately the biggest impact on Guyana’s forests and indigenous peoples will depend on national policies, not local projects.

Testing the “hands-on” approach

We will never know if a more “hands-off” approach with greater flexibility could have moved faster and with more agility to forestall deforestation—or what impact it would have had on indigenous peoples. However, we will get to see the results of being “hands-on.” The most lasting effects of REDD+ implementation in Guyana over the last nine years are typical of the “preparatory phases” envisioned by the UNFCCC prior to full-scale performance payments. These measures include establishing a forest monitoring system; adopting a low-carbon development strategy; and structuring a multi-stakeholder consultation process. Alone, these measures are unlikely to slow deforestation or protect indigenous peoples. Rather, progress will depend on the government tackling unresolved issues involving land rights and conflicts with extractive industries. In this regard, the interests of REDD+ and indigenous peoples appear closely aligned. Guyana needs REDD+ and rights.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.