The Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC), an independent US foreign assistance agency, was established with broad bipartisan support in January 2004. The agency was designed to deliver aid differently, with a mission and model reflecting key principles of aid effectiveness.

MCC has a single objective—reducing poverty through economic growth—which allows it to pursue development objectives in a targeted way. There are three key pillars that underpin MCC’s model:

-

Policies matter: MCC partners only with countries that demonstrate commitment to good governance on the premise that aid should build on those practices and reward countries already pursuing policies conducive to private investment and poverty-reducing growth.

-

Results matter: MCC seeks to increase the effectiveness of its programs by identifying cost-effective projects and investing only in those that promise to deliver positive development returns. MCC tracks the progress of its investments and has committed to measuring project impact through rigorous evaluations.

-

Country ownership matters: MCC works in partnership with eligible countries to develop and implement an aid program on the premise that investments are more likely to be effective and sustained if they reflect the country’s own priorities and strengthen the partner government’s accountability to its citizens.

MCC in Perspective

Annual Appropriations ($millions)

| FY04 | FY05 | FY06 | FY07 | FY08 | FY09 | |

| Request | 1,300 | 2,500 | 3,000 | 3,000 | 3,000 | 2,225 |

| Enacted | 994 | 1,488 | 1,752 | 1,752 | 1,544 | 875 |

| FY10 | FY11 | FY12 | FY13 | FY14 | FY15 | |

| Request | 1,425 | 1,280 | 1,125 | 898 | 898 | 1,000 |

| Enacted | 1,105 | 900 | 898 | 898 | 898 | TBD |

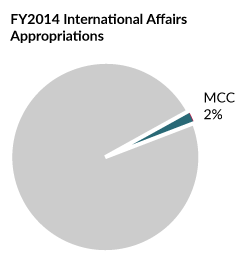

Though MCC is an important tool in the US government’s foreign aid toolbox and the only one designed to focus exclusively on development assistance, it is a relatively small agency.

Other includes Department of Health and Human Services (2%), Department of Energy (2%), Department of Defense (2%), Peace Corps (1%), and Department of the Interior (1%).

Picking MCC’s Partners

MCC partners only with low- and lower-middle-income countries that demonstrate commitment to good governance. [1] MCC determines country eligibility through a series of quantitative, third-party indicators that assess policy performance. These indicators fall into the three broad areas: ruling justly, investing in people, and economic freedom. MCC compiles these indicators into country “scorecards,” that the agency’s board of directors uses to inform its annual eligibility decisions. [2] In particular, the board considers countries that score better than half of their income-based peer group on the majority of the indicators. Most of MCC’s money goes to low-income countries (LICs), but MCC is allowed to dedicate up to 25 percent of its funds for lower-middle-income countries (LMICs) (see table 1).

The scorecards are the transparent, public face of the selection process, and MCC and its board weigh these quantitative assessments heavily. However, the indicators are incomplete and imperfect proxies for actual policy performance, so the board relies also on supplemental information to get a more complete understanding of candidate countries’ actual policy performance.

Table 1. MCC compacts (both number of programs and funds allocated) correspond roughly with the distribution of world’s low- and lower-middle-income countries, with the exception of South and Central Asia.

|

Share of Current LIC/LMIC Countries |

Share of LIC/LMIC Population |

Share of LIC/LMIC Poor ($2 a Day) |

Share of MCC Programs (# of compacts) |

Share of MCC Program Funds |

|

|

Africa (sub-Saharan) |

49% |

25% |

33% |

52% |

56% |

|

Asia / Pacific |

18 |

16 |

9 |

16 |

14 |

|

Europe / Eurasia |

6 |

2 |

1 |

12 |

10 |

|

Latin America / Caribbean |

10 |

2 |

1 |

12 |

11 |

|

Middle East / North Africa |

5 |

5 |

1 |

8 |

10 |

|

South / Central Asia |

12 |

50 |

55 |

0 |

0 |

Note: Data in this table refer to those countries that have signed a compact with MCC. The list of low- and lower-middle-income countries changes somewhat each year as countries’ incomes change. This table reflects the list as of FY2015, according to 2013 data on gross national income per capita, Atlas method (Source: World Bank). Twenty-three of the 83 candidate countries do not have recent poverty estimates (2005 or later). Of these, two-thirds are low-income countries (Burma, North Korea, and Solomon Islands in Asia/Pacific; Haiti in Latin America/Caribbean; Afghanistan and Uzbekistan in South/Central Asia; Comoros, Djibouti, Eritrea, the Gambia, Guinea-Bissau, Somalia, South Sudan, and Zimbabwe in sub-Saharan Africa) and one-third are lower-middle-income countries (Kiribati, Micronesia, Mongolia, Papua New Guinea, Samoa, and Vanuatu in Asia/Pacific; Kosovo in Europe/Eurasia; Guyana in Latin America / Caribbean; Syria in Middle East / North Africa). These countries were excluded from the “percent of LIC/LMIC poor” calculation, so these figures should be considered imprecise estimates. The high percentage of population and poverty rates in South/Central Asia is driven largely by India.

MCC Programs

MCC’s flagship program is the country compact. A compact is an agreement with a partner country in which MCC provides large-scale grant financing (around $350 million, on average) over five years for projects targeted at reducing poverty through economic growth (see table 2).

Table 2. MCC has signed 29 compacts with 25 countries.

|

Year of Signing |

Country |

Compact Total

|

Year Completed* |

|

2005 |

Madagascar |

110 |

2009 |

|

Honduras |

215 |

2010 |

|

|

Cape Verde |

110 |

2010 |

|

|

Nicaragua |

175 |

2011 |

|

|

Georgia |

395 |

2011 |

|

|

2006 |

Benin |

307 |

2011 |

|

Vanuatu |

66 |

2011 |

|

|

Armenia |

236 |

2011 |

|

|

Ghana |

547 |

2012 |

|

|

Mali |

461 |

2012 |

|

|

El Salvador |

461 |

2012 |

|

|

2007 |

Mozambique |

507 |

2013 |

|

Lesotho |

363 |

2013 |

|

|

Morocco |

698 |

2013 |

|

|

Mongolia |

285 |

2013 |

|

|

2008 |

Tanzania |

698 |

2013 |

|

Burkina Faso |

481 |

2014 |

|

|

Namibia |

305 |

2014 |

|

|

2009 |

Senegal |

540 |

|

|

2010 |

Moldova |

262 |

|

|

Philippines |

434 |

||

|

Jordan |

275 |

||

|

2011 |

Malawi |

351 |

|

|

Indonesia |

600 |

||

|

2012 |

Cape Verde II |

66 |

|

|

Zambia |

355 |

||

|

2013 |

Georgia II |

140 |

|

|

2014 |

Ghana II |

498 |

|

|

El Salvador II |

277 |

||

|

TOTAL |

10,216 |

Note: Current as of December 2014.

* Italicized completion dates indicate a compact that was terminated before its scheduled closure due to a military coup in the country.

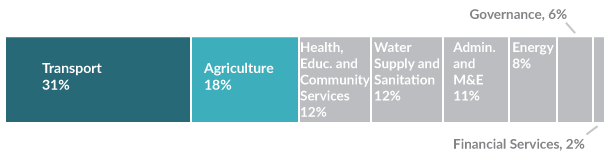

Figure 1. MCC compacts invest in a broad range of sectors, though countries often prioritize transportation infrastructure and agricultural development.

Source: MCC’s 2013 Annual Report, with FY2013 figures adjusted to include the Ghana II compact signed in August 2014 ($260 million added to Energy, $48 million added to Administration and M&E).

MCC also has a threshold program that supports targeted policy reform activities to help a country achieve compact eligibility. The threshold program is much smaller, accounting for only five percent of MCC’s total program spending since 2004. Countries typically complete threshold programs in two to three years. The average cost of a program is around $20 million. Approximately three-quarters of threshold programs have supported anticorruption policy reforms. Threshold program funds have also funded activities in other policy areas, including primary education, public health (immunization), business regulatory policy, and fiscal policy.

Table 3. MCC has signed 24 threshold programs with 22 countries.

|

Year of Signing |

Country |

Program Total

|

|

2005 |

Burkina Faso |

13 |

|

Malawi |

21 |

|

|

2006 |

Albania |

14 |

|

Tanzania |

11 |

|

|

Paraguay |

35 |

|

|

Zambia |

23 |

|

|

Philippines |

21 |

|

|

Jordan |

25 |

|

|

Indonesia |

55 |

|

|

Ukraine |

45 |

|

|

Moldova |

25 |

|

|

2007 |

Kenya |

13 |

|

Uganda |

10 |

|

|

Guyana |

7 |

|

|

São Tomé and Príncipe |

9 |

|

|

2008 |

Kyrgyz Republic |

16 |

|

Niger |

23 |

|

|

Peru |

36 |

|

|

Rwanda |

25 |

|

|

Albania II |

16 |

|

|

2009 |

Paraguay II |

30 |

|

2010 |

Liberia |

15 |

|

Timor-Leste |

11 |

|

|

2013 |

Honduras |

16 |

|

TOTAL |

512 |

Note: Current as of December 2014

MCC’s Model Incorporates Key Principles of Aid Effectiveness

When the MCC was created the international community was coming to consensus on principles that would make foreign aid more effective. A number of these principles are included in MCC’s model:

- ="" p="">

-

Have a clear, single objective. MCC has one, defined goal: achieving poverty reduction through economic growth. With this focus, the MCC pursues growth outcomes in a more targeted and more effective way than when development goals are blended with other objectives such as promoting stability, security, or nation-building. These are all important and reasonable objectives of US foreign assistance, but the multiplicity of goals can create ambiguity and undermine the effectiveness of development efforts.

-

Use rigorous economic analysis to choose projects. MCC commits to investing in growth-focused programs that will yield benefits—in the form of increased local incomes—that exceed the cost of program implementation. MCC’s partner countries use growth diagnostics to identify their binding constraints to growth, and MCC uses cost benefit analysis to screen for projects that will address those constraints in a cost-effective way. While almost all aid projects yield some benefit to someone, MCC’s processes seek to ensure that its investments generate sufficient benefits to justify the project’s costs. MCC is not the only donor to use these tools, but it is the only one to apply them systematically.

-

Predict, track, and measure results. MCC focuses on results from the outset. It is the only donor to link ex ante cost-benefit analysis of projects to performance targets. It has also set new standards for comprehensiveness, rigor, and transparency around evaluation and learning. Nearly 85 percent of the value of MCC’s portfolio is subject to independent evaluation; nearly half of these will use rigorous impact evaluation methods to identify attributable results (i.e., did MCC’s project actually increase household incomes in a cost-effective way?).

-

Emphasize country ownership. Partner countries develop proposals for how they will use MCC funding and take the lead role in project implementation. MCC’s flexibility to respond to country-led priorities is due largely to its predictable, multiyear funding for country programs and its freedom from Congressional earmarks. Because of these dynamics, MCC investments align far better than those of other US government agencies with what ordinary citizens in partner countries identify as their top priorities. [3]

-

Have time-limited partnerships. Compared to historically open-ended relationships that characterize traditional US foreign assistance, MCC compacts have a fixed five-year timeline. This limit provides incentive for timely implementation by the partner country, creates a clear exit from each compact investment, and forces reassessment of whether or not to continue engagement with a country.

-

Commit to transparency. MCC consistently publishes the tools it uses to inform investment decisions, quarterly updates of how compacts are progressing toward their targets, and the results of evaluations that show the extent to which MCC funds achieved their objective. [4]

Reward good governance. MCC selectively partners with countries based on their policy performance. MCC provides grants only to relatively well-governed countries that meet specific, transparent policy performance criteria. Moreover, it suspends or terminates funds if the quality of governance substantially deteriorates.

Ten years after its creation, MCC remains a compelling example of how foreign assistance can be structured to enhance aid effectiveness. Not surprisingly, the institution’s practices have not always been entirely consistent with its model. The agency has evolved over the past 10 years as rhetoric and best intentions encountered operational realities and political challenges. Consequently, there are a number of ways MCC could strengthen the implementation of certain aspects of its model, as outlined in CGD’s MCC at 10 series. But with 10 years of experience and a track record of more than $10 billion in programs, MCC’s application of aid effectiveness principles clearly and impressively distinguishes the agency from many other donors and provides a sound foundation for continued support of MCC’s operations.

Additional Resources

In the MCC at 10 series, Sarah Rose and Franck Wiebe take an in-depth look at three main pillars of MCC’s model: the agency’s focus on policy performance, results, and country ownership. To what extent has MCC’s model governed its operations in practice? How should MCC strengthen and expand its model and operations during the next 10 years? How is MCC different than other modes of US foreign assistance? Find the papers and more briefs like this one at CGDev.org/page/mcc-ten.

[1] MCC candidate countries are those that have per capita incomes (Atlas method) less than or equal to $4125 (for FY2015) and are not statutorily restricted from receiving US foreign assistance.

[2] MCC’s board is made up of five government representatives—the Secretary of State, the USAID Administrator, the Secretary of the Treasury, the US Trade Representative, and MCC’s CEO—as well as four private representatives suggested by Congress (one each from the majority and minority of both the House of Representatives and the Senate) who serve in their individual capacities.

[3] Benjamin Leo. 2013. “Is Anyone Listening? Does US Foreign Assistances Target People’s Top Priorities?.” CGD Working Paper 348. Washington, DC: Center for Global Development.

[4] For the last two years, MCC has ranked in the top three out of over 65 donors on Publish What You Fund’s Aid Transparency Index. http://ati.publishwhatyoufund.org/

Rights & Permissions

You may use and disseminate CGD’s publications under these conditions.