The Bottom Line

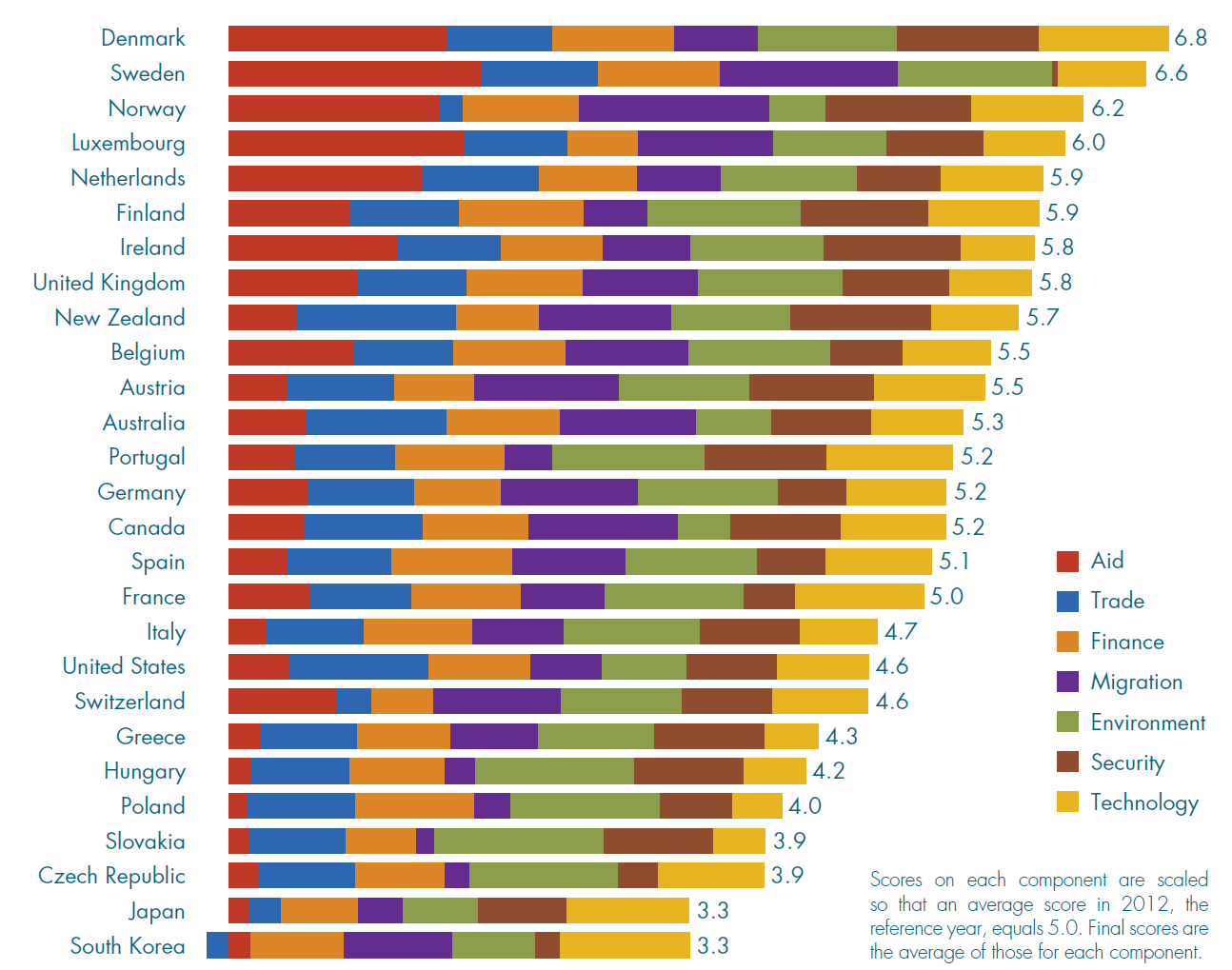

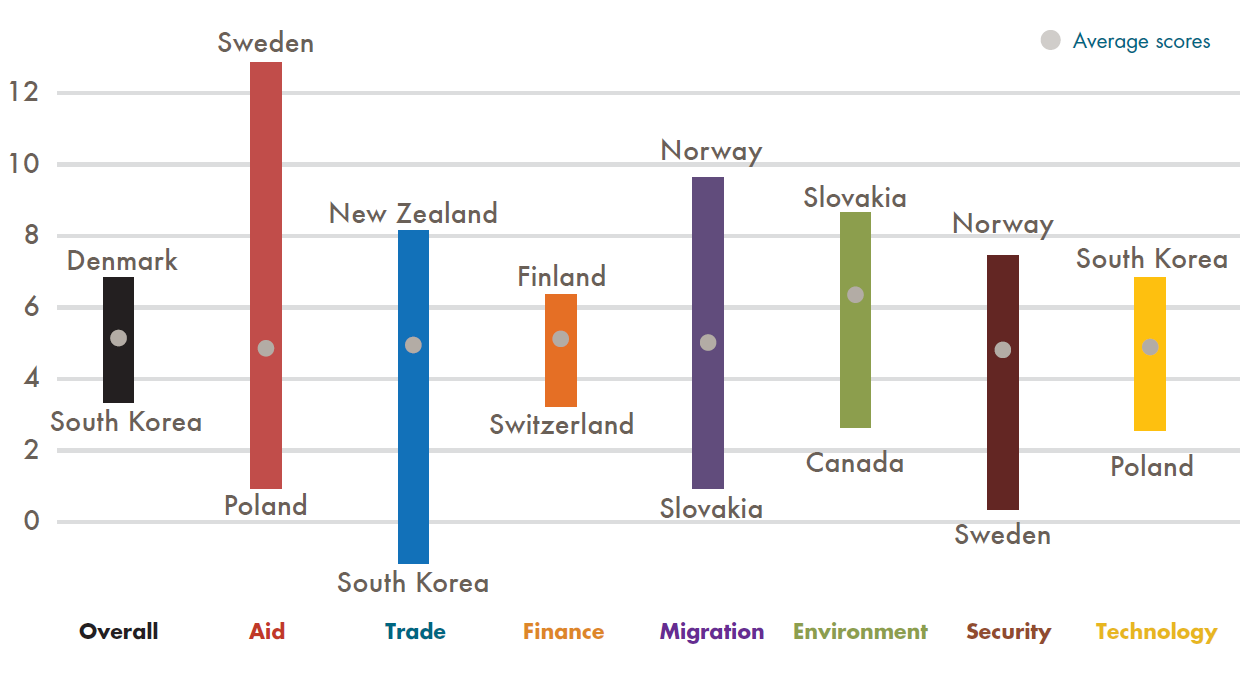

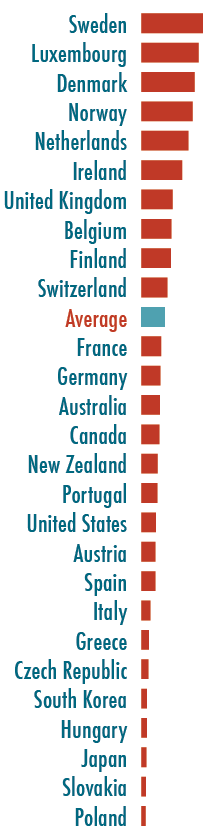

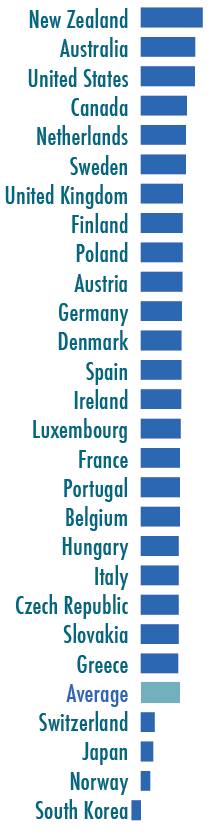

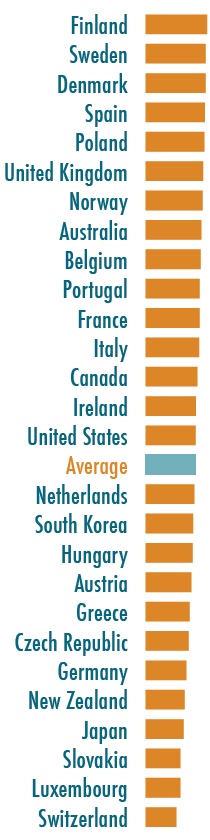

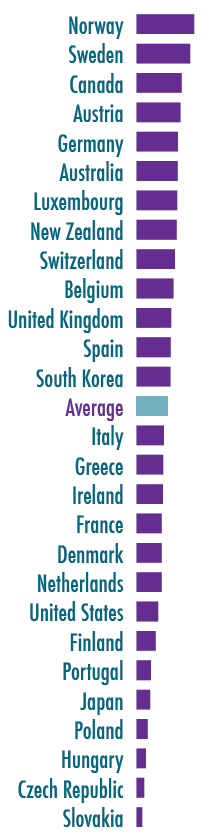

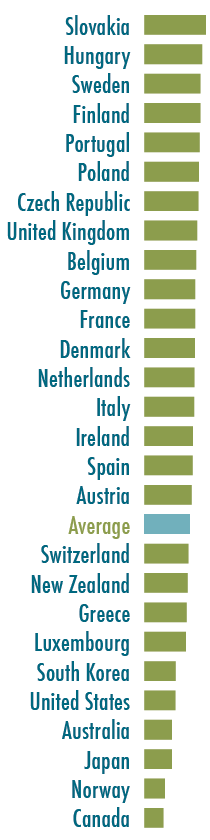

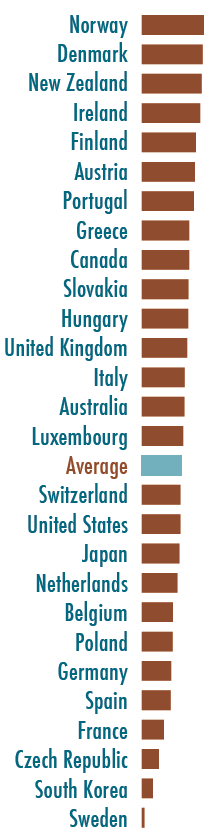

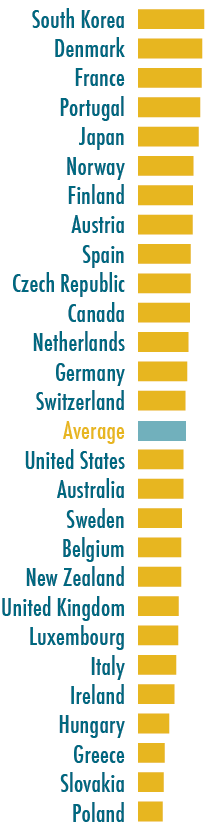

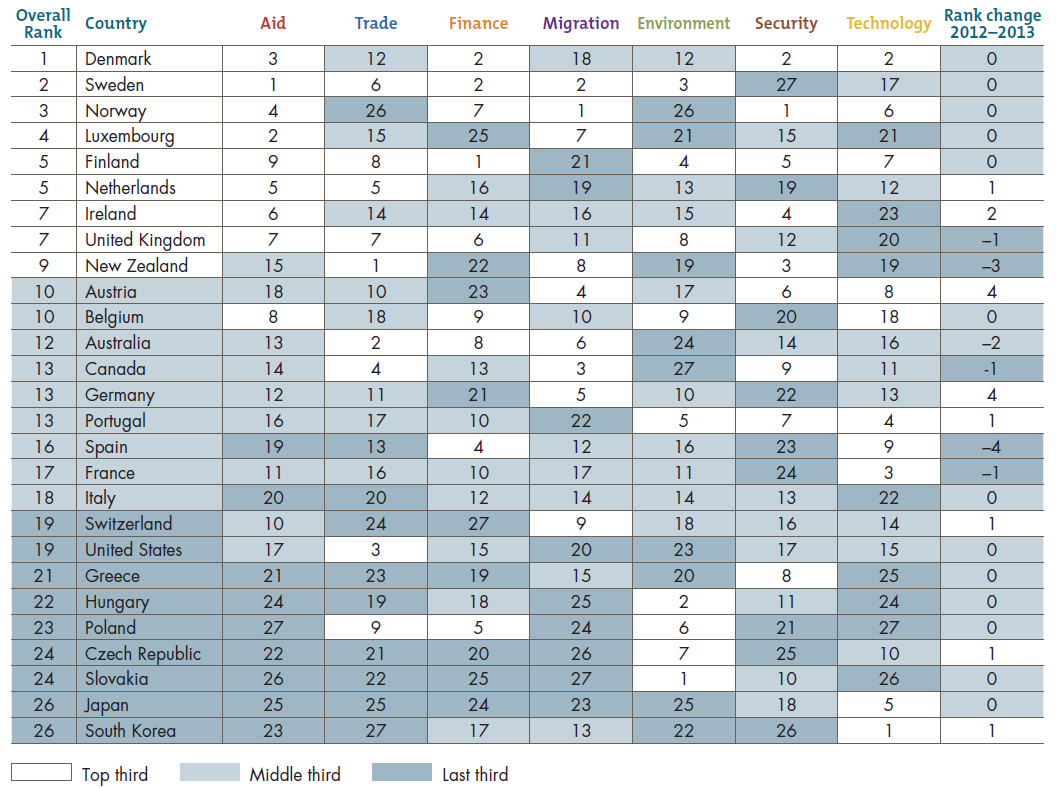

For the second year in a row, Denmark ranks first on the CDI because of its high aid quantity and quality, transparency in its financial sector, and commitment to security in developing countries, and because it spends a significant portion of GDP on developing new technologies. Close behind are Sweden, Norway, and Luxembourg, all top-ranked aid donors with strong migration records. Norway ranks number one in two CDI components—migration and security. New Zealand and Austria place in the top half with very different profiles: both generally score low on aid, but New Zealand is strong on trade and security while Austria is particularly strong on migration. Among the G–7 countries—those that matter most by dint of their economic power—only the United Kingdom places in the top 10. The United States scores below average in all but the trade component. Japan and South Korea finish last with small aid programs for their sizes, tight borders to the entry of goods and people, and limited involvement in peacekeeping. They are joined near the bottom by Hungary, the Czech Republic, Poland, and Slovakia, which rank at or below average in all components except for environment, where they occupy top spots. Still, even the first-place Danes are only average in three of the seven policy areas, but unlike all other CDI countries they have no below-average score.