Recommended

POLICY PAPERS

Ten years ago, only six out of every hundred people living in low-income and lower-middle-income countries had access to the internet. Today, nearly one out of every three does. Efforts by the world’s largest internet companies—particularly Facebook and Google—to reach the “next billion users” have been a key driver of this transformation.

The “next billion users” moniker gained popularity in 2005 as the number of people online crossed the one billion threshold. Since then, it has become convenient shorthand for people who can’t access the internet, an increasing share of whom live in the developing world. Today, more than 65 percent of the roughly four billion people in the world without internet access live in countries with a per capita GDP of less than $3,895 a year (the cut-off point between lower-middle and upper-middle-income countries, according to the World Bank’s classification scheme).

Sources: ITU (2018) ICT Indicators Database, Pathways For Prosperity Commission Analysis

Despite their low average income, the next billion users have become an increasingly important target for US internet companies seeking to expand their footprint outside of rich world markets where the number of potential customers not already online has dwindled.

To reach the next billion users, tech companies have tailored their products to a more difficult operating environment and a different set of user needs. This includes developing applications that work well on mobile phones and in areas where connectivity is often slow and the cost of data can be prohibitively high (e.g., a phone and data plan cost the average customer in 15 African countries more than 20 percent of their monthly income).

Facebook and Google stand out from their competitors in both the amount of resources they’ve dedicated to wooing the next billion users and the success they’ve had:

-

Over 70 percent of Facebook’s 2.3 billion monthly active users live in Africa and Asia, and India recently surpassed the United States as the country with the most users (250 million). WhatsApp, which Facebook acquired in 2014, now boasts more than 1.5 billion monthly active users, making it the most popular messaging app in the world.

-

Google operates domains in roughly 200 countries and territories and offers services in over 100 languages. Some estimates of the company’s market share in online search are as high as 92 percent, and its Android operating system powers more than two billion devices worldwide.

Reflecting their commercial imperative, both companies have focused their efforts in the developing world on populous countries with growing middle classes, such as India, Nigeria, Indonesia, and Brazil (for the moment, China remains off-limits). But their map of engagement continues to grow: for example, both Facebook and Google are working with partners to lay hundreds of miles of fiber optic cable in Uganda, Africa’s 10th most populous country.

Challenges ahead

The rapid expansion of internet use throughout the developing world is welcome news. But it raises the same concerns about society’s growing reliance on big tech companies that rich countries are just beginning to address. These include the challenge of protecting consumers in the digital age, the role of social media platforms in promoting disinformation, and the risk that market concentration will stifle innovation.

In a new paper coauthored with my colleague John Polcari, we use these three areas of concern as a frame for exploring what the rapid growth of Big Tech in the developing world means for policymakers there grappling with how to maximize the economic and social benefits internet platforms provide while minimizing their risks.

While there is a risk in lumping together countries with starkly different socioeconomic characteristics into a single “developing world” bucket, we believe doing so is useful for several reasons. First, with notable exceptions like China and India, most developing countries have limited, if any, leverage over large internet companies, given their small size and low-income per capita. Second, because many people in the developing world often have fewer tools at their disposal to cross-check information, they may be more easily exploited by efforts to misuse their personal data and more susceptible to propaganda campaigns conducted online.

Finally, although developing countries are equally if not more vulnerable to some of the risks raised by digital platforms, little work has been done to consider how policymakers there should approach these challenges. And while there is broad agreement in the development community on the importance of getting digital policy “right,” too little attention has been paid to how policymakers can best engage with the companies who dominate the digital landscape. It is therefore not surprising that, as the Pathways for Prosperity Commission has emphasized, “few developing countries have a clear approach to [the] foundational question of digital governance and even fewer, if any, have a clear approach to regulating digital design and user protection.”

Breaking up is easy to do

Today, a growing number of governments are reassessing how they engage with internet companies with an eye towards gaining more control over how the data generated by their citizens is used. Recent examples of such “data localization” policies include India’s draft data privacy bill, which recommends forcing firms to store a copy of all personal data provided by Indian consumers in the country, and Vietnam’s cybersecurity law, which requires internet companies to open representative offices in Vietnam and provide user data to the government when requested (which critics argue will be used to stifle online dissent).

While more research is needed to understand the economic impact of data localization policies—and while the impulse to capture some of the value attached to data produced within a country’s borders is understandable—most of the economic arguments made in favor of these policies appear unconvincing. Simply put, forcing companies to store data on local servers will not change where value-added processing takes place, but it will raise the cost of doing cross-border business. The cyber security justifications for data localization also seem doubtful.

A more pressing concern is that an increasing number of governments have shown an interest in adopting China’s authoritarian model, which uses digital tools to support surveillance and stifle dissent—and Chinese officials appear eager to share their expertise. According to Freedom House’s Freedom on the Net 2018 report, “[last] year, Beijing took steps to propagate its model abroad by conducting large-scale trainings of foreign officials [from at least 36 countries], providing technology to authoritarian governments, and demanding that international companies abide by its content regulations even when operating outside of China.”

These trends endanger the (mostly) global and open nature of the internet. And while it may be naïve to think that governments attracted to the idea of using internet policy for repression could be persuaded to choose a more liberal path, this is the task at hand for those who seek to preserve an open internet that supports democratic rights.

A better path

Concerns about the internet’s drift towards fragmentation can be traced back to the mid-2000s (see for example Tim Wu’s 2004 blog) but the trend appears to have accelerated in recent years. The best way to confront this shift is to address head-on the challenges that a free and open internet presents. This will require a comprehensive approach that includes the following elements:

-

Greater leadership by the United States. Because the United States is home to the world’s largest internet companies, it benefits more than any other country from an open internet and finds itself in a natural position of authority. To date, however, it has ceded this authority by taking a hands-off approach towards regulating data-driven tech companies.

While the European Union has pursued a tougher regulatory stance on competitiveness and data privacy, the absence of effective regulation by the United States has allowed its internet companies to operate with less regard for these concerns in most countries and undermined the ability of other governments to address them.

Now that attitudes on Capitol Hill about regulating internet companies appear to be shifting, US policymakers should recognize that the choices they make will affect how these companies operate abroad and shape the set of regulatory options available to policymakers in other countries, particularly lower-income ones that lack the economic heft necessary to influence large tech firms on their own.

-

Building an evidence base. One possible reason for the lack of consensus around how governments should engage on these issues is the absence of a conceptual framework around the value of data, as reflected by the ongoing debate about whether oil or labor is the more useful historical analogue for data’s role in the digital economy.

A more coherent theory of data’s economic value and a means to measure that value would help governments design more effective digital strategies. Developing such a framework will not be easy, however, as it will require finding ways to (1) estimate the worth of disparate pieces of personal data whose value depends on being combined with other data to produce useful information, and (2) track the value of data across multiple uses.

The good news is that technologists are now exploring new ways to enhance the transparency of this combinatorial process and give internet users more control over how their personal data is used. If successful, these efforts could make it easier to track how individual pieces of data flow through the digital economy and to measure their value. Ultimately, it may even be possible to develop input-output tables for data like those used to account for value-added production in global value chains (h/t to Toby Philips for this idea). This analysis could serve as the basis for better-informed negotiation between governments and internet companies.

-

Better global coordination. Global internet governance is usually associated with the multistakeholder approach that evolved out of the communities that created the internet and later the web. While that approach has been successful in dealing with matters related to the internet’s technical architecture, such as ICANN’s handling of domain names, it has been unable to address socially contested issues.

In the absence of better mechanisms for global coordination, sovereign nations have asserted control of internet regulation with little heed to the cross-border implications of their actions. But the increasingly political and social nature of the debates around internet policy argue in favor of considering when global solutions may be appropriate. For that reason, the recent announcement by Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe that Japan will develop a data governance track for this year’s G20 Summit was encouraging.

The rationale for global coordination over digital policy will be strongest in areas where cross-border spillovers are more immediate or where the efficiency gains from coordination are greater. Data privacy arguably falls into the latter category because harmonizing privacy standards could reduce the cost of compliance for globally active companies. While a government’s approach to data privacy will necessarily reflect how it prioritizes values like transparency and freedom of speech, economic considerations will also be a factor, increasing the potential for global coordination.

An open internet is a global public good that provides myriad social and economic benefits for its users. For that reason, preserving it should be a policy priority for the development community as well as policymakers in the developed world. While there is no guarantee that taking the steps outlined above would slow the trend towards a fragmented internet, they are necessary conditions for success.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.

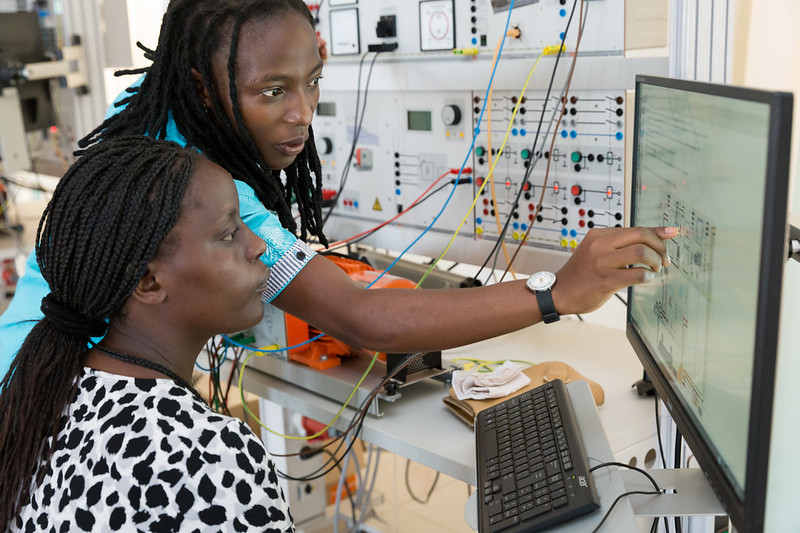

Image credit for social media/web: Torrenegra/Flickr