When US Treasury Under Secretary David Malpass appeared before Congress just five months ago, he indicated that the World Bank “currently has the resources it needs to fulfill its mission” and went on to characterize the bank and other multilateral institutions as inefficient, “often corrupt in their lending practices,” and ultimately only benefitting their own employees who “fly in on first-class airplane tickets to give advice to government officials.”

From that standpoint, it would be hard to imagine US support for a significant injection of new capital into the World Bank’s main lending arm, the IBRD, as well as the bank’s private sector lender, the IFC.

And yet, that’s exactly the surprising outcome just announced at the World Bank’s spring meeting of governors. Not only is the Trump administration supporting a $7.5 billion capital increase for the IBRD (and at that, one that is 50 percent larger than the capital increase supported by the Obama administration in 2010), it has also signed on to a policy framework for the new money that makes a good deal of sense.

Here are the highlights:

-

The capital increase package will better enable the institution to deliver on its commitment to be a leader on climate finance and more broadly in support of global public goods, aligning with key recommendations from CGD’s 2016 High Level Panel on the Future of Multilateral Development Banking. Under the agreement, the climate-related share of the IBRD’s portfolio will rise from the current 21 percent to 30 percent. The IFC’s share will rise even higher to 35 percent. New ambition on the climate agenda also includes commitments to screen all bank projects for climate risks and incorporate a carbon shadow price into the economic analysis of projects in emissions-producing sectors. For global public goods more generally, the agreement newly commits a (very modest) share of IBRD annual income to global public goods.

-

The package introduces the principle of price differentiation based on country income status, with higher income countries paying more than the bank’s other borrowers. This proposal, which was also put forward by CGD’s High Level Panel in 2016, will generate additional revenues for the bank and asks more of countries that have less financing need. While the introduction of the principle marks an important step forward, the actual price differentiation is extremely modest—at most, the spread between high income borrowers will be just 45 basis points on IBRD lending rates of about 4 percent.

-

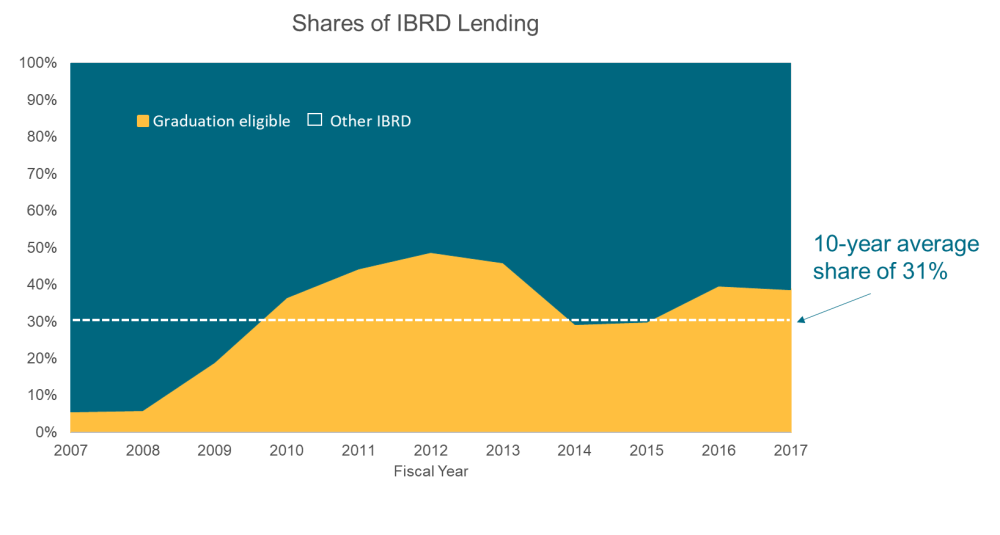

The package assigns new guidelines for the IBRD’s overall lending portfolio to channel 70 percent of the bank’s resources to countries with per capita incomes below $6,895 and 30 percent to countries above this so-called “graduation threshold.” These targets would not be binding when it comes to crisis lending. In practice, these new guidelines seem to align with the existing pattern of IBRD lending, as indicated in the figure. In this sense, the idea that these guidelines amount to cutting China's access to World Bank loans appears exaggerated, though over time, as more countries join the higher income category, the 30 percent share will be allocated across more borrowers.

-

The package also attempts to identify a new financial framework that requires greater discipline when it comes to tradeoffs between lending volumes, loan pricing, and the bank’s administrative budget. This framework, which reportedly was a priority for the US government, may not ensure that this will be the last ever capital increase for the World Bank (as an unnamed US official promises), but it does appear to introduce a greater level of coherence around financial/budgetary decisions that have historically proceeded in a disjointed fashion within the institution.

-

Finally, even as the agreement seeks greater differentiation among countries, it reaffirms the World Bank’s commitments to stay engaged with all its client countries, including China. In fact, given US rhetoric, it’s surprising that the agreement does not stake out any new ground on the subject of country graduation. In fact, it seems to go out of its way to reassure all current bank borrowers that they are still welcome and that the decision to graduate from assistance is theirs to make. In the end, as much as ending China’s borrowing from the bank would have been a political prize for the Trump administration, US officials appear to have taken a sensible policy path that favors good incentives over polarizing fiats.

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise.

CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.