Recommended

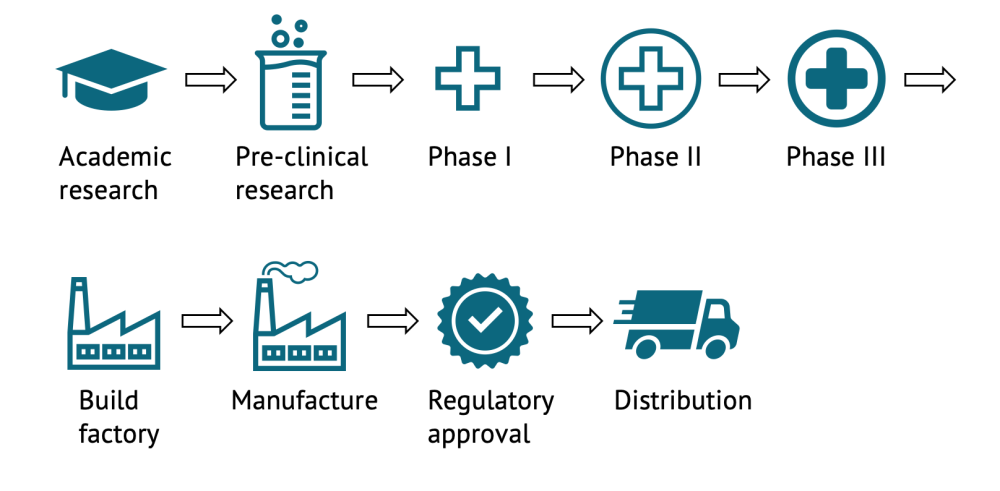

Much of the discussion around society’s ability to return to “normality” after the COVID-19 pandemic has centered on the development of a vaccine. This has led to unprecedented collaboration and investment. Vaccine candidate development for COVID-19 is progressing faster than for any other pathogen in history. Governments, pharma, and foundations are all pouring hundreds of billions into the science, which has hastened discovery and development. There are currently more than 200 vaccine candidates being pursued, in 30 different countries, mostly based on one of seven different development approaches (though there are a few complete outliers). Each candidate is scientifically unique and could potentially play an important role in battling this deadly disease. As vaccines complete the different phases of development (pre-clinical, phase I, phase II, phase III, regulatory review, and license), results will be published in the scientific literature and announced to the public through the media and press releases. We are currently working as part of a larger group to interview experts and give better guidance on the timelines and probabilities of success for a vaccine against COVID-19. In the meantime, it is important not to read too much into early stage results—this is why.

Phase I is too early to tell—especially with a disease we still know so little about

After a phase I trial, we really know very little about a candidate. The early phase I and II trials tend to enrol healthy adults and the numbers are quite small (often hundreds for a phase I only in young adults, compared to the 30,000 representative population expected for a phase III trial). They are intended to see if the vaccine can elicit an immune response and some basic information about what the response looks like, to test different dose sizes or dosing regimens, to ensure that the vaccine is well tolerated, and at what level it is generally safe. Failure to produce an immune response or any severe adverse reactions tell us the candidate is not likely to be of use. But positive results do not tell us anything about adverse events that are rare in healthy young adults.

We also don’t know very much about the vaccine’s effectiveness based on phase I and II trials: a vaccine that fails to generate an immune response will not make people immune to COVID-19, but the reverse is not necessarily true. We need much larger and differently designed trials to know if the response created by these vaccines will protect us against infection. This is difficult for all diseases, but much more so for COVID-19 as we still know comparatively little about it. In a disease that has been in the human populations for a while, or ideally where we already have an imperfect vaccine, we already know the characteristics we would expect in the immune system of someone who had acquired immunity, known as the “correlates of protection.” For COVID-19 we really don’t know what these correlates look like, making interpreting phase I trials near impossible. Even if this does confer immunity, we do not know how long this immunity will last. We can only confirm immunity lasts and how responses relate to various protection levels for as long as the trial tracks participants

Results can be slanted

People tend to work on projects they believe in, both because it is unusual to commit large amounts of time and energy to projects that they think are doomed to fail and because optimism bias leads people to believe that their projects are more likely to be successful than is actually the case. This means if you ask people how likely their product is to succeed, they will likely earnestly overestimate their chances of success.

This optimism is compounded by strong incentives to release promising results. Companies are not obliged to announce interim results. They do so usually to impress shareholders and investors. This is true for all research but particularly right now as investors and governments make huge decisions quickly, such as the very recent $2 billion dollar funding announcement for Pfizer by the US government. This leads companies to tend to accentuate the positive. Governments right now are also under incredible pressure to convince their citizens that they are doing all they can to end this crisis and that the hundreds of millions invested in select candidates were worth it; they are thus incentivised to promise results. Indeed the media are biased towards definitive, headline-grabbing clarity, not the incremental, caveat-laden reality of scientific progress.

Important to challenge statements

Of the 1,838 industry sponsored vaccine candidates that completed a Phase I trials in the first two decades of this century, 1,517 (82.5 percent) continued on to Phase II, but of those that cleared phase I, less than 40 percent were eventually approved. Progression to the next round of research and development should not be a surprise. Yet when on the 20th of July Oxford and AstraZeneca released early stage results from their phase I trial, more than half the UK’s national newspapers ran the story as their lead article the following day. Only one did not declare it a breakthrough, with several stating with confidence that we were likely to have a vaccine by Christmas. Similar fanfare has happened when other candidates have released interim findings, like when Moderna released findings on the 14th of July.

Leaders, governments, pharmaceutical companies, and the media are not only overstating likely scientific success, they’re also overstating what success means.

The stock market has also reacted positively to phase 1 results, with share prices rise for the company involved, but the market as a whole lifts on the slightest positive vaccine news. This is probably symptomatic of wider optimism from non-vaccine experts, and may impact how phase I results are reported in media and other non-peer reviewed outlets.

Leaders, governments, pharmaceutical companies, and the media are not only overstating likely scientific success, they’re also overstating what success means. First-generation vaccines are usually replaced by better second-generation vaccines because the unknowns are too great to create a highly effective vaccine on the first attempt. It is for this reason that the US Food and Drug Administration is only requiring that a vaccine be 50 percent efficacious in order to be approved, meaning that it halves the chances of contracting the infection, but likely more than halves the chances of dying from it. Indeed, many experts we have spoken to suggest that this is likely as good as we will get for a first-generation vaccine. While there would be benefits to a vaccine with 50 percent efficacy, it's a far cry from the 70-80 percent efficacy that it is thought we need to obviate the need for social distancing. The value of such a vaccine would be further lowered by the fact that many people will likely refuse to take it. Also left out of much of the news coverage, is the fact that if we find a vaccine by December, it could be a long time before we have enough of it to adequately dose the global population. That brings us to another challenge: how to think about allocating vaccine during the ramp-up interval when there is insufficient supply. We will tackle that puzzle in a future post.

When leading vaccine candidates start to fail (and some almost certainly will), it has the potential to undermine credible science. Worse still, there’s a chance that in our haste to develop a vaccine, we buy and administer a suboptimal or even unsafe candidate. We are deeply worried that this would augment distrust in vaccines that has long been increasing in high-income countries.

This pandemic has impacted most people’s lives, and the decisions that we all make on how to deal with this crisis going forward will be profoundly shaped by estimates of how long the crisis will last. If overly optimistic, people could be deterred from making decisions or investments needed to sustain some social distancing effort over time. Finally, as governments make unprecedented investments in late-stage pharmaceutical research, we worry that the optimistic press reduces scrutiny of what are some of the most important research and development (R&D) decisions made in our lifetime.

We need greater clarity and better reporting standards

With roughly 200 candidates in the pipeline, we believe we need a standardised reporting template all journal editors and manufacturers agree on, and ideally an independent process for reviewing the data as they come out. At the moment it is very difficult for policymakers, investors, and the general public to understand what’s going on. This is a case where regulators and payers ought to come together with scientists to follow and comment on results and set reporting standards in the process. Regulators must demand standardisation in trial design and reporting, in testing protocols/thresholds, and reagents. This would help give everyone a better sense of what is going on. We also need better clarity on how governments assess where to put their money, based on some sort of scientific committee to evaluate probability of success.

Modelling timelines and probabilities of success

We are all working as part of a wider group to better answer some of these questions. Our first aim is to give independent probabilistic estimates about when a vaccine might be rolled out, to help improve decision-making. If, for example, there is an 80 percent chance of rolling out a vaccine in 2021, investment decisions that firms, hospitals, and schools ought to make will be very different to if there’s an 80 percent chance we won’t. Secondly, by analysing the R&D pipeline and the manufacturing capabilities, we hope to identify if there are areas where we’ve underdiversified our risk, or potential blockages in the manufacturing chain that can be rectified. This would help to improve policy in this area and, ideally, help avoid future bottlenecks.

We are interviewing vaccine experts from academia, industry, and government in order to generate estimates for the probabilities of success and timelines around COVID-19 vaccines. We will aggregate these inputs and release them in a paper that we hope to publish in August. These will be used as inputs into a model we are creating that we hope can estimate timelines for success as well as identify bottlenecks in both R&D and manufacturing. We will build this model so that people can test these assumptions with their own inputs.

This should make it easier for governments to make investment decisions through objective and rigorous probability of success estimates. It will help to correct for optimism bias, which is simply part of human nature. It will also provide objectivity, which will lead the market to set rational expectations. Otherwise the downsides in the stock market when they realize they overestimated probabilities of success will be larger than the upswing.

We are only halfway through the interview process, so it is too early for us to release any preliminary results. But what we can say at this point is that the interviews thus far suggest that the best vaccine candidates have at best a 50 percent chance of success. Many interviewees have flagged the risk that these candidates may take longer to approve and manufacture than anticipated—R&D projects rarely finish ahead of schedule but often overrun. Considering the global disruption to the health and livelihoods of all nations, the imperative to end transmission of this novel virus and distribute safe and effective vaccines is indisputable. So while we desperately hope that the world has a vaccine by the end of the year, we should all continue to study the trials and make sure we have backup social distance holiday plans in case the picture is not quite as rosy as some newspapers, scientific journals, and politicians would have you believe.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.