Recommended

POLICY PAPERS

Development agencies are spending unprecedented levels of development finance on climate-related objectives—but how much impact is that finance having? As negotiations towards a new climate finance target progress at the UN, we hope to add to the number of voices urging that the new goal encompasses not just quantity but also quality of climate finance.

Building on our previous work, which identified six challenges to ensuring climate finance effectiveness, this ongoing blog series will delve deeper into issues related to the quality of climate finance.

In this blog, we highlight how a persisting climate-related “evidence gap” is currently leaving providers ill-equipped to design and deliver programmes effectively—especially within climate change mitigation. Despite over $38bn-worth of Official Development Assistance (ODA) projects citing climate mitigation as an objective in 2022, we find that providers currently have access to just 31 mitigation-related impact evaluations.(This ratio is much lower than for most other policy priorities where ODA is channelled.) On top of this, we find that a lack of standardised metrics and outcome indicators used in climate-related impact evaluations is further reducing opportunities for mutual learning and complicating cross-provider comparability. We argue that providers must do more, and work together, to comparably measure, assess and learn about the impact of the billions of tax-payer funds invested in international climate action.

“So before spending all of your climate budget …. you might want to know whether that is going to work or not.” Esther Duflo , 2019 Nobel Prize Winner in Economics

The climate evaluation gap in the context of other development priorities

In order to assess global efforts on evaluating the more than $73bn of public finance from bilateral and multilateral agencies in “developed countries” which is spent annually on international climate objectives, we analysed over 14,000 evidence-based studies collected by the International Initiative for Impact Evaluation (3ie). 3ie’s Development Evidence Portal is the largest international repository of its type, collecting high-quality evidence—including impact evaluations, systematic reviews, and evidence gap maps—across a broad range of interventions in low- and middle-income countries, covering all sectors.

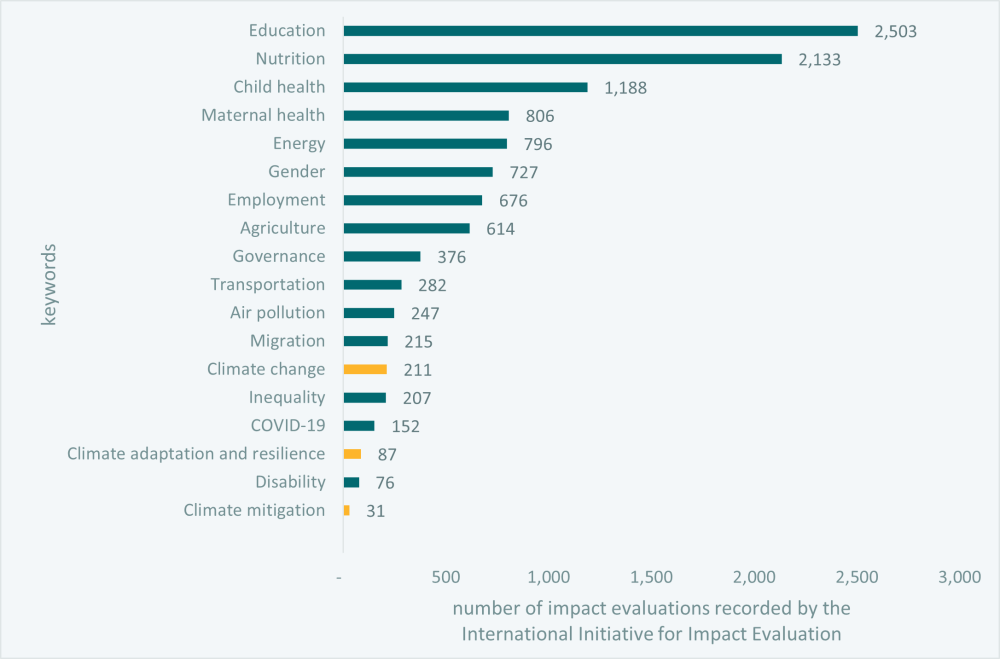

We found that climate change is very poorly covered in high quality impact assessments. Of over 13,000 impact evaluations, we found just 211 which mention “climate change” at all. Only 87 evaluations have been tagged as relating to climate change “adaptation” or “resilience”, while even fewer—just 31—are tagged with climate change “mitigation” (Figure 1). This not only compares poorly with the numbers of evaluations tagged with keywords related to other cross-sectoral priorities and sectors—including, for instance, 2,133 for “nutrition”, 727 for “gender”, or 247 for “air pollution” —but also remains out of sync with the substantial and increasing shares of Official Development Assistance (ODA) which providers claim target climate-related objectives.

Figure 1. Number of impact evaluations recorded by key words

Source: 3ie

Note: The relevant key words were searched for with 3ie’s query tool, and included mentions of the relevant words within the impact evaluations’ title, abstract, or “keywords” functions. Specific search queries and links to results available on request.

Climate finance providers are also challenged by the paucity of climate-related "systematic reviews". These are vital as through synthesizing findings across multiple interventions, they provide insights across a variety of geographical, sectoral, or financial contexts, giving more clues on the pre-conditions for global climate project success. Yet, of over 1,100 systematic reviews in the 3ie database, we found only seven climate-related systematic reviews , of which only two met 3ie’s methodological criteria of a “high confidence” level.

While, to some extent, this scarcity of climate-related publications may partly stem from the fact that climate finance is still a relatively new type of flow as compared to other types of development interventions, it’s also notable that other newer development challenges—like COVID-19—have already garnered nearly as much evaluative insight, despite their relative novelty. There has been an uptick in the publication of climate-related studies over the past decade—growing at roughly double the average rate, or 35 percent annually between 2013-23, compared to 17 percent across all 3ie publication records—but it's crucial to recognize the significant gap that still exists. Even if current growth trends continue, climate change-related evidence will not match the volume of nutrition-related evidence for another 16 years—or until 2039!

Dollars without direction—quantifying the evidence gap

We find that each billion of climate-related ODA committed can only rely on only a handful of evaluations to inform projects’ planning and delivery. For every $1bn of ODA channelled towards adaptation to climate change in 2022, we estimate that fewer than 3 relevant evaluations were available, and this ratio was even lower for mitigation finance, with fewer than one study published for every $1bn committed. By contrast, in other “cross-cutting” priorities tracked through the OECD’s marker system, such as nutrition or gender, providers were able to draw on a relatively more substantial evidence base (Table 1), with each billion of ODA targeting nutrition able to draw on over 100 previous studies, and each billion of gender-related spending being able to rely on 11 evaluations.

Table 1. Ratio of available studies in 3ie database to 2022 ODA, by cross-cutting priority

|

Cross-cutting policy objective |

Relevant evaluations per $1bn of ODA |

Relevant impact evaluations |

Commitments in 2022 ($mn) |

Principal |

Significant |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Nutrition |

136 |

2,133 |

15,695 |

1,770 |

13,924 |

|

Gender |

11 |

727 |

65,226 |

5,274 |

59,952 |

|

Disability |

5 |

76 |

16,001 |

328 |

15,673 |

|

Governance |

9 |

376 |

40,198 |

18,146 |

22,051 |

|

Biodiversity |

4 |

44 |

11,022 |

3,204 |

7,818 |

|

Climate Change Adaptation |

2.5 |

87 |

34,498 |

5,936 |

28,562 |

|

Climate Change Mitigation |

0.8 |

31 |

38,709 |

18,448 |

20,262 |

Source: OECD and 3ie

Note: Based on DAC providers’ ODA commitments. A cross-cutting policy objective is based on the OECD’s marker system which denotes where a project (within any sector) has a ‘principal’ or ‘significant’ objective in one of these areas. Multiple markers may apply to the same project.

Mitigation-heavy sectors, such as energy, are especially under-evaluated

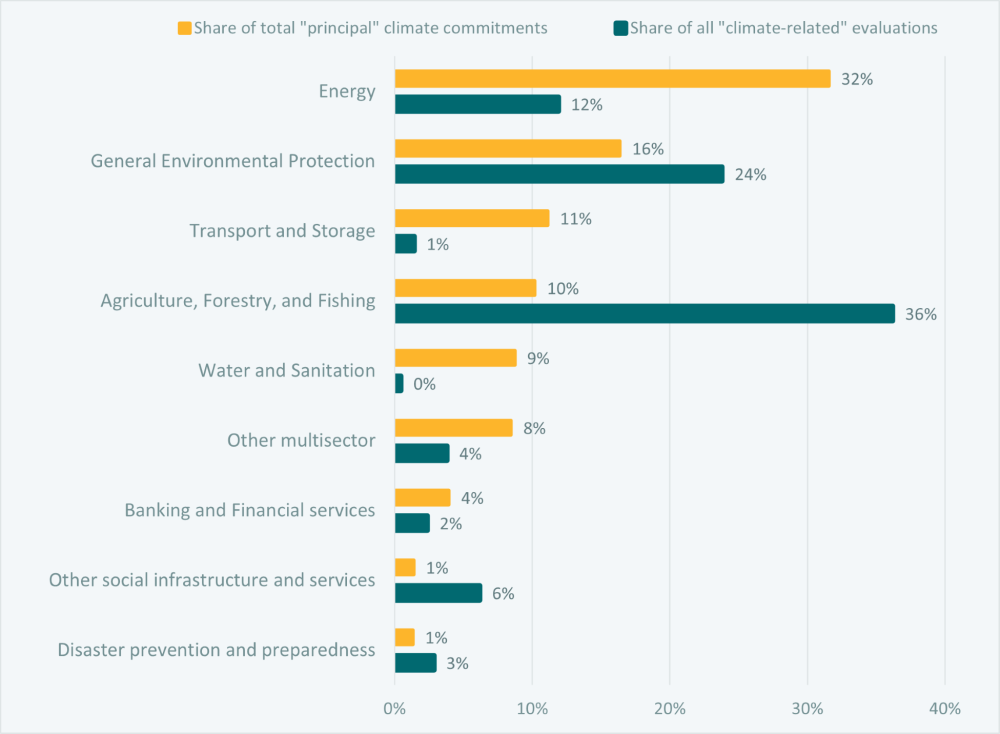

Within the already relatively small pool of climate-related studies, evaluation effort varies significantly by sector. Just three sectors—energy, transport, and water sanitation and hygiene—account for over half of the financial volume of ODA tagged as having a principal climate objective, yet, collectively, projects within these sectors only accounted for 13 percent of all climate-related evaluations recorded in the 3ie database. Meanwhile, climate projects within the agriculture and “general environmental protection” sectors can draw guidance from a relatively larger evidence base —especially when compared to the levels of finance spent.

Figure 2. Climate-relevant sectors, as a share of concessional climate finance, and as a share of climate-relevant impact evaluations since 2016

Sources: OECD and 3ie

Note: Only data since 2016 is considered, both for financial volumes, and for evaluations. This is because, as the 3ie notes, filters for impact evaluations recorded in the 3ie database which were published before 2016 may be incomplete. Sectors which represent less than 2% of total climate-relevant impact evaluations as well as less than 2% of the principal climate spending since 2016 are not shown.

Greenhouse gas guesswork: lack of common metrics hampers comparability

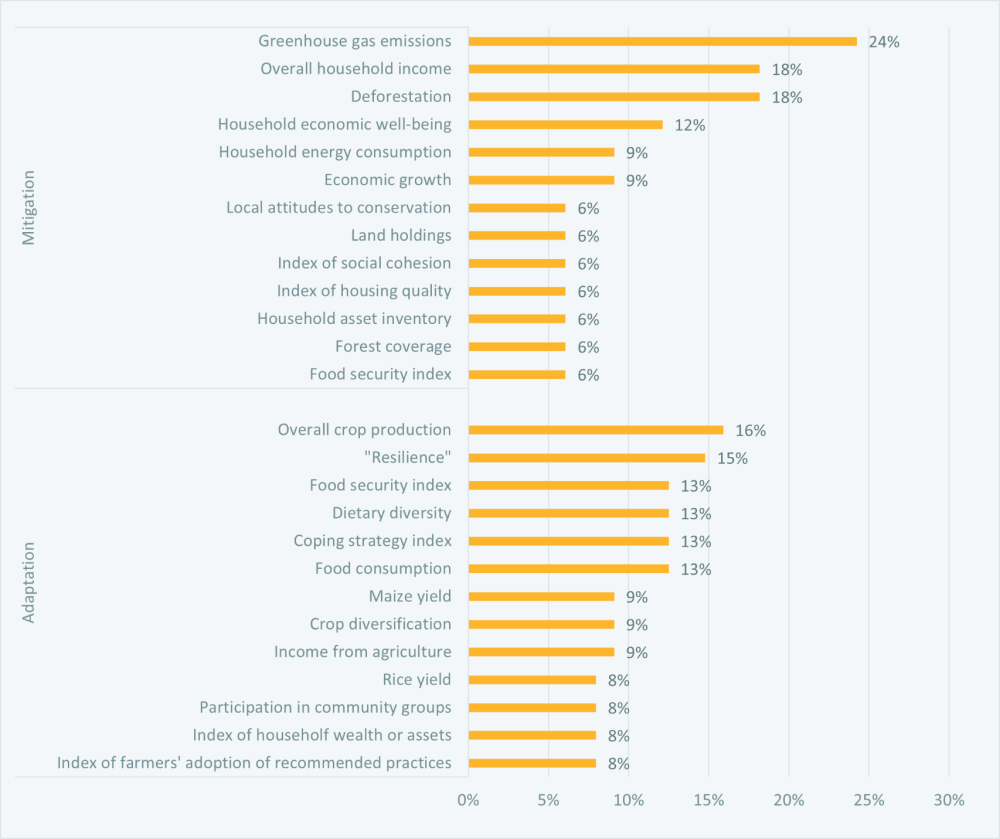

Evaluation efforts are also hampered by a lack of common metrics and methodologies for evaluating climate project success, compounded by a lack of transparency from providers on the expected and achieved results of their climate projects. In our scan of climate-related studies included in the 3ie database, we discovered a wide array of "outcome" measures tracked, with over 100 different measures identified for adaptation-related impact evaluations and over 70 for mitigation-related evaluations.

This diversity of outcome measures assessed is especially perplexing in the mitigation space, where, in theory, one measure could be reported and assessed consistently across all projects—no matter where they take place. While climate change mitigation projects funded by ODA are also likely to be expected to yield other local "co-benefits”, where mitigation is listed as the “principal” goal, the primary measure of success (greenhouse gas emissions reductions) remains inconsistently assessed. Our analysis reveals that just under a quarter of climate mitigation-related impact evaluations in the 3ie database have evaluated greenhouse gas emissions as an outcome measure (Figure 2). The lack of focus on emissions hampers comparability between the cost-effectiveness of mitigation projects, impedes a more optimal allocation of financial resources to deliver on the target to limit global warming to 1.5°C, and also hinders more informed discussions on the balance between “global” and “local” benefits expected from concessional development finance dedicated to delivering global public goods.

Figure 3. Most frequently assessed “outcomes” of climate-related impact evaluations

Source: 3ie

Note: GHG emissions include “emissions from agriculture”. The results in this figure rely on 3ie’s filter function, which 3ie warns may be incomplete for studies conducted before 2016. To minimise the risk of including studies which have not yet been fully coded, we used regular expressions in the advanced query tool to filter out those publications which have no outcome measures recorded.

A need to align standards for reporting and results

Further complicating this issue is the fact that both greenhouse gas accounting methods and reporting standards differ across climate finance providers, and leave a margin of uncertainty when trying to compare between projects from different funders on a like-for-like basis. While the work of 25 International Financial Institutions (IFIs), including 13 Multilateral Development Banks, to harmonise greenhouse gas accounting standards has been promising, no equivalent standard exists for bilateral development agencies, and it remains unclear what—if any—impact their “mitigation” ODA is actually having on emissions. In practice, even providers who are part of this IFI working group still face accounting issues related to establishing emissions baselines and inconsistent criteria in areas like inclusion thresholds or sectoral coverage. What’s more, the significant number of projects funded by these IFIs through intermediaries are not subject to the same monitoring criteria. Also, despite some commitments to do so, few funders make information on the emissions reductions of their individual mitigation projects systematically and publicly available–as we previously noted.

For adaptation-focused projects, where both results are more likely to be specific to each local context as compared to mitigation, defining universal outcome indicators at the global level may be an inherently more thorny issue. However, from the perspective of assessing collective progress and sharing best practices, there is still value in comparing approaches to measuring results and developing common frameworks metrics – in fact, this has already been a focus of ongoing discussions in the lead-up to the NCQG, with work for the Global Goal for Adaptation in 2021 concluding in a technical report mapping the landscape of indicators, approaches, targets and metrics used for adaptation finance. This review revealed a very wide variety of approaches for “tracking adaptation effectiveness” across providers, raising important questions around how and whether indicators used in adaptation projects could be standardised or defined to support reporting at aggregated levels.

Translating intentions to impact

A dearth of climate-related evidence leaves providers without the necessary information to programme climate projects effectively. This means that opportunities for optimizing climate resource allocation, ensuring climate projects’ cost-effectiveness, and maximising overall impact may remain unrealized. Providers should step up their efforts to invest in evaluation, coordinate their efforts to measure results; and ensure they share them and learn the lessons.

With climate finance volumes very likely to rise in the coming years, there remains a substantial risk that any additional resources will still not be able to achieve the desired results at scale. This could leave developing countries to bear the brunt of the impacts and tax-payers within provider countries disappointed.

With the New Collective Quantified Goal (NCQG) to be set by the end of the year, we will continue to offer our insights into the key challenges to ensuring climate finance is programmed and delivered effectively in the next instalments of this blog series.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.

Image credit for social media/web: rolffimages / Adobe Stock