Thirty national governments and over 235 organisations from more than 60 countries have signed the Girl Summit Charter (PDF) advocating for an end to female genital mutilation (FGM) and child, early, and forced marriage “within a generation.” The charter was launched on July 22nd as part of the Girl Summit jointly hosted by the British government and Unicef.

It’s not controversial to argue against early marriage purely on child rights grounds, but of course the phenomenon has broader development implications. Research suggests that early marriage is associated with a raft of negative effects on children and their communities, in part by making girls less healthy and less educated.

One of the charter’s several aims is for countries to curb underage marriage by legislating against it. In a speech opening the summit, British Prime Minister David Cameron argued that child marriage needs to be outlawed “everywhere, for everyone.” While the 1964 UN Convention on Consent to Marriage pushed governments to set and enforce minimum age restrictions, it did not specify a minimum age.

So will new legislation actually be an effective way to battle child marriage? Mr. Cameron himself acknowledged that laws on their own won’t work unless cultural practices and social mores change, too. The efficacy of a spate of new child marriage bans ultimately depends on how willing national governments are to enforce their own laws.

We would like to believe that legislative change is enough, but as the American statistician William Deming put it: “In God we trust; all others bring data.” If the minimum marriage-age laws currently on countries’ books don’t work, we should be pretty skeptical that new ones will.

Taking the question to the data

To put some structure on this problem, we used data from the Demographic and Health Surveys, filtering for the most recent survey round available for any country that had a survey in the last decade, giving us a total of 50 countries. We extracted responses from married women under 30 about their age at marriage and added in information from the UN about the legal age of marriage.

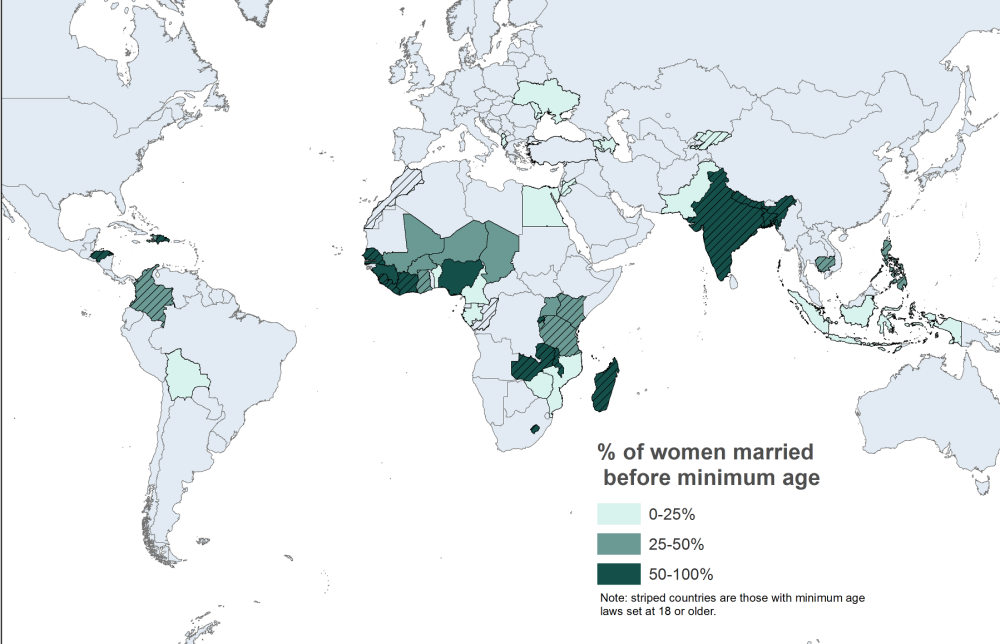

A useful way to visualise this is a map of the share of women in each country who report being married below the legal age. (Child and early marriage also affects boys and men, but we focus on girls and women here because they are much more frequently victims of these practices).

In 32 of the 50 countries we map, more than 25 percent of married survey respondents report being married before their country’s legal limit. Put simply, current laws aren’t working.

Searching for spikes

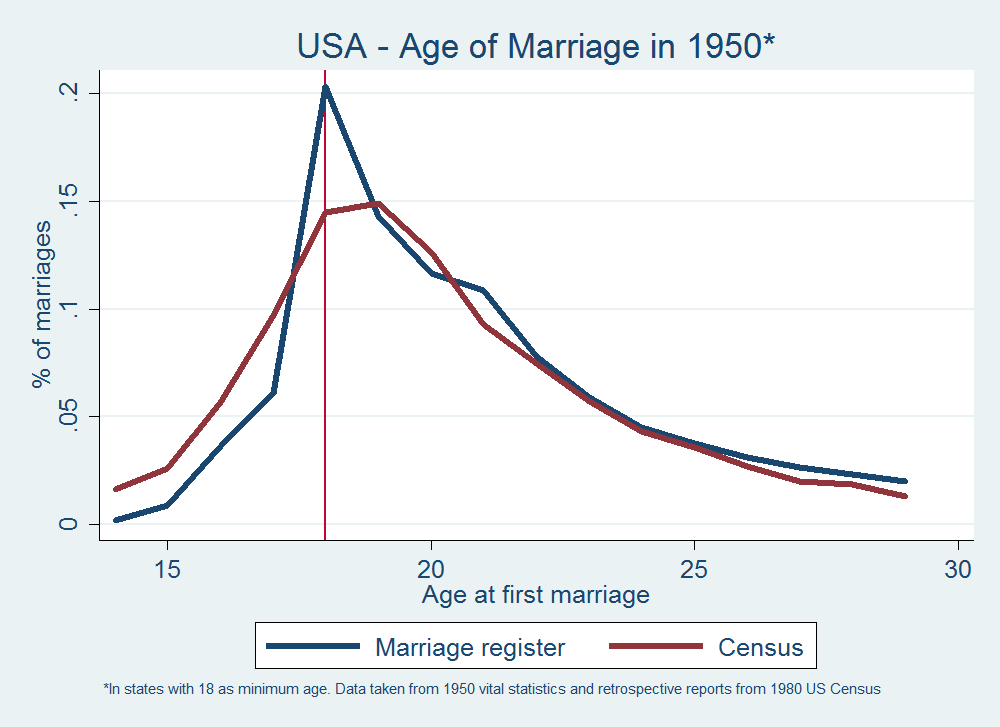

What should we see if those laws were enforced? The economist Rebecca Blank (now the Chancellor of the University of Madison–Wisconsin) and her co-authors provide an elegant answer in a recent paper: if minimum-age laws make people wait to tie the knot, the distribution of women’s marriage ages should show a “spike” around the legal cut-off. Their paper uses US data to show that while these spikes show up in official marriage registrars in the 1950’s, they don’t appear in census data. As our replication of one of their key graphics shows, Americans were ducking minimum-age laws in large numbers in the none-too-distant past.

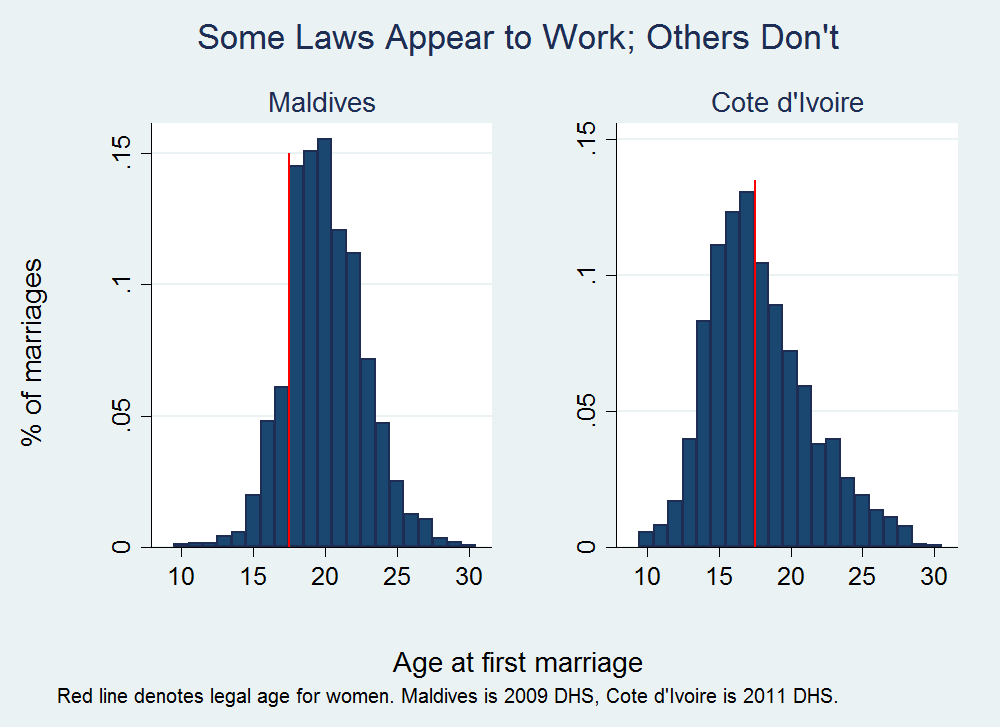

With Blank et al.’s way of checking for the effectiveness of marriage laws in mind, we would like countries to be like the Maldives, on the left, where we see a striking discontinuity around the age of marriage, denoted by the red line — too many girls are being married too young, but it looks like some people are waiting until they reach legal age.

Unfortunately, our world map and the vast majority of the country-level graphs show that most are like Cote d'Ivoire on the right. (The legal age happens to be 18 in both countries). Not only do we see no jump at the legal age of marriage, we see a decline. (Interested readers can click through here for a PDF of the age-at-marriage distributions for countries in our sample).

We haven’t presented any formal statistical tests of these spikes around marriage ages, and such tests couldn’t tell us whether laws were effective compared to what might have happened in their absence. Minimum-age rules could also have longer-term effects social mores and cultural norms, and agitating for legal change can focus attention on the broader issues at stake.

But as the charter itself puts it, “legislation alone is not enough.” We couldn’t agree more. In a world where women and girls face violence, discrimination, and forced marriage, taking the question of legal efficacy to the data confirms our suspicion: a global ban can only be the starting point of our collective push for change.

The Stata code and data we used to produce the figures in this post are available here.

Update: The original version of this blog post mistakenly indicated the minimum age-of-marriage in Burkina Faso to be 18, when it is actually 17. This updated version uses Cote d'Ivoire as an example instead (as the minimum there is 18). The Burkina Faso graph is still available in the PDF linked above.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.