Recommended

School meal programmes are among the few social sector initiatives that generate equally high enthusiasm from governments in both the poorest and the richest nations. Even in these times of turbulence and uncertainty, most governments are highly protective of their national school meal programmes. However, this enthusiasm is not shared by everyone. Mention school meals in low- and middle-income countries to an international development expert, and they’re likely to raise sceptical questions about whether such investments are good value for money to improve test scores. But raising test scores has rarely been the driving motivation for landmark decisions to institute or significantly scale up school feeding programmes–which has been happening since the beginning of the 20th century. Neither is it the only, nor even the main consideration for most governments that are currently starting or expanding national school meals programmes in many parts of the world.

To mark this year’s international school meals day, I have reviewed some of the key moments and milestones for school meals around the world over the past century or so (see Fig 1). These experiences show the extent to which school meals interventions have been interwoven in the policy choices countries had to make at some critical junctures in their modern history. My hope is that providing this historical perspective will counteract the reductionist tendencies that are common in contemporary international development discourses on school meals today.

Figure 1: Main motivations for decisions to establish or expand national school meal programmes around the world

School feeding was a key part of modern nation building in Western Europe

School feeding programmes in many industrialised countries emerged over a century ago as part of broader social transformation following economic development and democratic consolidation. The emergence of school feeding programmes largely overlapped with the expansion of public education in Europe and America in the latter half of the 19th and early 20th centuries. As such, the responsibility of providing meals to needy pupils began shifting from non-state actors or local organisations to the state.

In many western societies, school feeding schemes evolved organically, roughly following the same pattern as the rest of the modern welfare state. This means private charities, religious organisations and local municipalities which generally provided social assistance to fill the gap created by the weakening of traditional forms of solidarity were also the pioneers of school feeding in the 19th century. Typically, these schemes sought to address locally identified problems of child poverty and malnutrition observed among the expanding school population.

Germany was one of the first countries to attempt to nationally institutionalise school feeding programmes that had flourished across cities in a fragmented manner. However, a bill that was introduced in the Reichstag in 1897 to provide school meals in all cities was defeated on the grounds that its passage would cause an influx of people to the large cities. A few years later, Holland became the first country to enact a national legislation authorising municipalities to supply food and clothing to children who might fail to enrol into school for lack of resources.

In Britain, the school feeding agenda received a boost from an unusual source, following a series of reports on the physical deterioration among young British men issued in the aftermath of the Boer war. The commission recommended school meals be provided to needy children, creating a peculiar precedent in which the national security implications of nutrition gave impetus to school feeding. The recommendations of the commission coincided with grassroots advocacy of education activists such as Margaret McMillan who insisted compulsory education should be accompanied by school feeding schemes. The British experience offers further examples as to how broader reform of public education, for instance the reorganisation of education management into Local Education Authorities, was coupled with the introduction of school meals.

Similarly, in the US, the push for institutionalising school feeding at the federal level gained momentum with the introduction of compulsory education which some considered to be “an utter folly” without the requisite sustenance to facilitate learning. Generally, the need for school meals must have been amplified by the confluence of a significant increase in income inequality and the political drive to invest in public education as a nation building tool in the early 20th century. At least in the UK, the political impetus for state-sponsored school meals is difficult to separate from the groundswell of support for other social policy measures such as the old age pension, which was driven by the organised labour movement.

We can see the role large-scale systemic shocks have played in increasing the momentum for school meal programmes through examples like the rapid rollout of federal assistance for school feeding in the US as part of the recovery programme during the Great Depression. As well as supplying meals to school children in the midst of an economic slump, the programme also created employment for 7442 women in 1933-34 and was used to mop up excess supply of agricultural output caused by the depression, protecting farmers’ incomes. The provision of school meals in Germany in the aftermath of World War II (which was spearheaded by former US president Herbert Hoover) represents an early example of the use of school feeding in large-scale reconstruction and rehabilitation efforts after a major war.

Emerging countries have applied a more progressive interpretation of development to implement school meals.

Developing countries embarked on the twin agenda of fighting poverty and investing in education following decolonization, in the case of former colonies, or the rise of modernising regimes. Although there has been an element of gradual organic growth in some countries, the lessons of industrialised countries and the guidance of international organisations such UN agencies played a significant role in the emergence of school feeding in many developing countries. In Brazil, where school feeding had been in place in some of the more disadvantaged regions earlier, it was not until a proposal by UNICEF was put forward in 1946 that the programme was institutionalised at the national level.

The increasing recognition of “second generation human rights” in the decades following World War II has influenced the conception of school feeding as a versatile tool to promote education and prevent child hunger in developing countries. As such, some countries adopted a rights-based approach in introducing or further institutionalising school feeding programmes at a national level. The ruling of India’s Supreme Court in 2001, directing the government to fully implement its scheme of providing cooked meals to all children in primary schools, stands out as the most famous example of this approach. Additionally, India’s case is notable for the role the Supreme Court plays in ensuring compliance via the appointment of independent Commissioners.

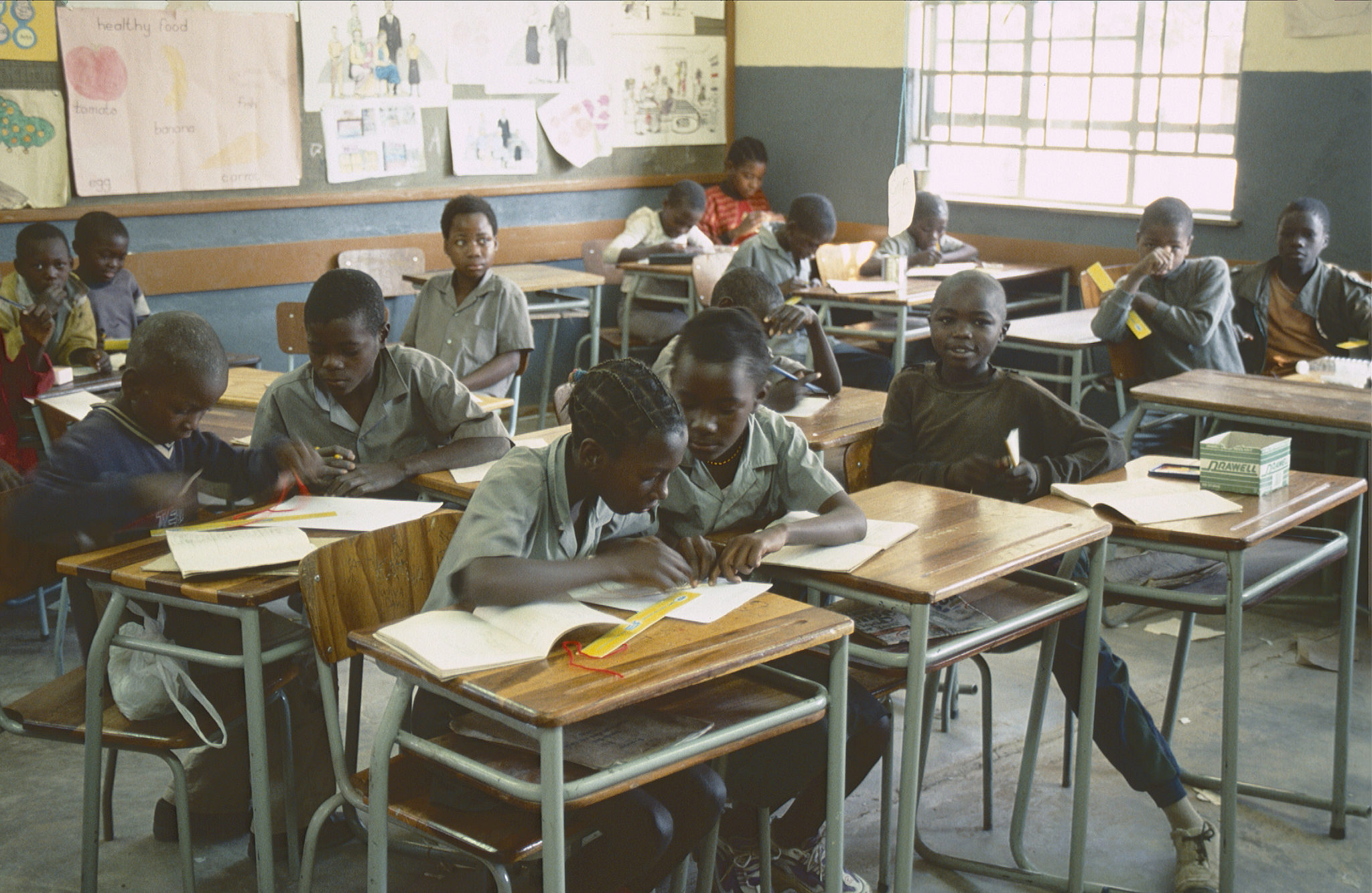

Another variant of the rights-based approach is presented by South Africa, where a progressive constitution designed to address the dramatic injustices and inequities of the recent past laid the foundation for deploying school meals as part of a package of social protection measures following the fall of apartheid. South Africa also represents a case in which school feeding was first introduced as one piece of an integrated nutrition programme, aimed at preventing hunger, before it was later moved to the education ministry.

Compared to the preceding cases of middle-income countries where a distinct legal/political decision or transnational diffusion of best-practice shaped the trajectory of school feeding, China’s experience falls on the gradualist end of the spectrum. The evolution of school feeding in China seems to have tracked the path of development of its economy. Economic transformation provided the fiscal space to finance school feeding programmes which in turn helped to address social needs partly created as a result of the process of economic change. For instance, the comprehensive school health and nutrition interventions introduced since 2011 are especially targeted at children who are left behind in rural areas by parents mostly employed in the manufacturing sector in urban areas.

There has always been more to school meals than test scores

It is no coincidence that school meal programmes often emerge in the wake of significant social change. All of the above episodes in the history of school meals around the world involved policy considerations for broader human development or social protection beyond the narrow metrics of student test scores. This does not mean that school meals cannot be used to improve learning outcomes, nor does it imply that feeding school children can replace other interventions to enhance education quality. But, applying a restrictive lens of effectiveness in a single outcome to determine the social desirability of school meals is not only reductionist but also ahistorical.

If a programme that came of age in the Victorian era remains the most ubiquitous social safety net programme at the dawn of the AI age, there must be something good about it.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.