Boquillas del Carmen is a tiny village just over the Rio Grande from Big Bend National Park in Texas that experienced a tremendous decline when US authorities closed the border in 2002. For decades, the town’s economy depended on tourists crossing over to enjoy spectacular views of the Chisos Mountains while eating homemade enchiladas at the one or two restaurants in town. Many would also buy beautiful wire sculptures of scorpions, road runners, or other local handicrafts. You had to pay a couple of dollars to someone to row you across the river, known as the Rio Bravo in Mexico, because there is no bridge there. And if you didn’t want to walk, or just preferred the fun of it, you could pay someone else to take you up the hill to the village on a burro. My brother and I made that trip with our parents when we were small and on a spring break camping trip to Big Bend.

The Rio Grande River from Boquillas del Carmen, Mexico

The Rio Grande River from Boquillas del Carmen, Mexico

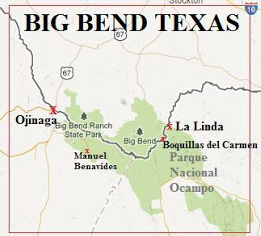

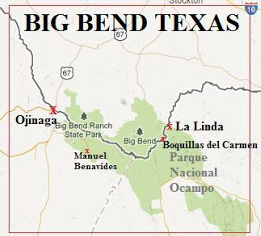

Then, some months after the attacks of September 11, 2001, the US government shut down all unofficial, unmanned border crossings with Mexico, including the one at Boquillas. Suddenly there were no more tourists. And local residents could no longer cross into the United States to buy groceries and other supplies. The closest legal crossing after 2002 was at Ojinaga, some 200 miles of punishing, mostly dirt, roads away. The population of Boquillas shrank from around 300 to roughly 100 and the restaurants and bars closed. Many, like Lilia Falcon, who succeeded her father in running the family restaurant overlooking the river, left and came to the United States to find work.

US/Mexico border

US/Mexico border

Under pressure from locals on both sides of the border, as well as park officials who wanted to make crossing easier for scientists and the elite Mexican firefighting team stationed in Boquillas, US authorities reopened the crossing in 2013. The rowboat is back, as are the donkeys, and the tourists are coming back as well. My husband and I recently visited Boquillas and had lunch at the reopened Falcon’s restaurant. The January weather was spectacular, as were the views. And on our way back, we saw a man returning from the US side with piles of groceries that would have been far more difficult to get to Boquillas without the new crossing.

The re-opening has been a win-win for people on both sides of the border. A broader cooperation agreement on temporary labor movement could do even more to enhance prosperity on both sides of the border. The details are in this report written by Michael Clemens and based on the deliberations of a CGD working group chaired by former Mexican President Ernesto Zedillo and former US Commerce Secretary Carlos Gutierrez.

And, despite criticism and President Trump’s threat to withdraw from the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) if Mexico does not agree to unspecified changes, that agreement has also been a win-win for most people in both countries. According to one back of the envelop calculation, the United States is $127 billion richer and Mexico is $170 billion richer as a result of the additional trade spurred by NAFTA. The agreement is not without warts—improvements in working conditions in Mexico, including narrowing of the wage gap with the United States, have not been as broad or deep as expected. But a recent empirical study estimates NAFTA increased overall Mexican welfare by 1.3 percent and 0.08 percent for the United States. Some might take these statistics as evidence that it is a bad deal for the United States. But the disparity in benefits reflects key differences in the two economies. First, total merchandise trade in Mexico, most of it with the United States, adds up to nearly 70 percent of the economy there, versus just 20 percent in the United States. Second, average Mexican tariffs were twice as high as the already low average US tariffs prior to NAFTA.

Shortly after my return to Washington, President Trump issued an executive order calling for construction of the border wall that he had promised to build during the campaign. Imagine the view from Boquillas with a wall in the foreground. Imagine what that policy would do to the people of Boquillas, and to so many others throughout the hemisphere.

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise.

CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.