Recommended

Aid-financed climate finance investments account for around a quarter of global aid—but we still know very little about how effective this spend is. Today we publish a policy paper in which we analyse the only systematically reported impact data for climate mitigation projects reported from two of the largest climate finance multilaterals. These projects demonstrate a wide variation in the cost of mitigating a tonne of carbon—with half of projects doing so for less than $41 but some projects costing several hundreds of dollars per tonne.

Our analysis suggests improvements need to be made to ensure mitigation funding has the intended impact. We estimate that a focus on effectiveness could plausibly reduce emissions by an amount equivalent to a year of the UK’s emissions. Here, we draw out three reforms that should accompany any new finance commitments.

The concessional climate finance spend is large, but impacts are unclear and uneven

Governments’ international climate investments are now almost $80bn per year according to the OECD’s analysis, of which over half is aid; and most is on climate mitigation. But there is very little evaluation evidence on what impact that spend is having.

In our new policy paper, we analyse $6.9bn of investment across 120 projects, 40 from the Green Climate Fund and 80 from the Clean Technology Fund, demonstrating that project cost-effectiveness differs by orders of magnitude both within and between sectors, whether co-financing is included or not. These funds lead their peers in transparency by publishing these results, with most funds and all development agencies only publishing headline figures on impact, but no complete set of project-by-project cost-effectiveness data. Here we propose that agencies supporting mitigation projects with concessional finance adopt three reforms to ensure climate finance effectiveness.

First, report expected and actual climate impacts

The GCF and CTF deserve credit for assessing and publishing the expected climate impacts of their projects. Other multilaterals like the Global Environment Facility, as well as bilateral funders and development banks that are financing climate mitigation, should also be systematically reporting their project-level expected and actual emissions mitigation performance. Even the UK—who is traditionally strong on transparency, and has committed over £2bn per year for its International Climate Finance funding vehicle for years beginning 2021 to 2025—doesn’t publish a dataset of the project-level impacts of that now 10-year-old bilateral effort.

This is particularly important for projects whose primary aim is climate mitigation, where the goal of emissions reduction is a shared undertaking globally. Indeed, given this common goal, these results should be reported to a common standard. Below, we set out a proposal for that standard, and also suggest a role for a body—a climate impact observatory—to collate evaluations and results of climate impact and identify learning in the approach.

Second, incorporate transformational benefits

As the world works towards net zero emissions, all finance will need to become consistent with that goal. If public money is used, it should be focused where it can have the greatest effect. In many cases, funders and projects are rightly pursuing “transformational” impacts—that is, leading to wider reduced emissions in the sector or region beyond the scope of the funded project. A good example might be the first use of a particular renewable technology, like wind power, whose demonstration in a particular context leads to wider uptake.

However, in the projects we reviewed, whilst potential for transformational change was often claimed as a core aim, quantification of the likely impact was sometimes absent from project documents, and never reported in the headline dataset of expected results. Furthermore, the estimates we did find didn’t include any measures of uncertainty, like the probability of success. One good-practice example in the CTF portfolio includes a scenario where a 100MW geothermal project in Chile “could” demonstrate the potential of geothermal energy in the region and lead to a further 800MW installed capacity in the medium term, resulting in further mitigation. This gets halfway there, but to be fully useful for decision making the probability must be quantified, as well as the possible effect.

Climate mitigation project planning must consider any potential transformational impacts in the regional or sectoral greenhouse gas performance. However, the possibility of such impacts should not serve as a vague fig leaf for poor cost-effectiveness in the short term. Rather, it must be quantified, and should be included in summary data across projects.

Climate impact reporting

Agencies undertaking projects with the main aim of climate mitigation should ensure every project quantifies seven distinct elements:

1. estimated (ex ante) emissions averted - from approved proposals

2. actual (ex post) emissions averted to date - from management information

3. final (ex post) emissions averted - from rigorous impact evaluation

4. cost of mitigation measures and full project cost

In addition, as the primary aim of this finance is to catalyse transformations in the sector and recipient country’s wider emissions pathway, projects should

5. estimate averted emissions the project could catalyse, and

6. assign a probability to create an ‘expected’ value.

Finally, in projects that include private sector participation,

7. the size and grant element of agency finance and other public finance.

Third, assess cost-effectiveness and beware “weak synergies”

We identified some evidence (though very little of high quality) that pursuing mitigation alongside air pollution reduction, public health, and biodiversity outcomes can lead to what we call “strong synergies.” These synergies are improvements in the effectiveness of one or both outcomes, relative to projects addressing only one.

But we also identify projects with “weak synergies”—that is, those which imply a large reduction in cost-effectiveness on one outcome to achieve results on the other outcome. For climate, this is where the costs of unlocking mitigation were disproportionate to the mitigation gained. In one example, for a project that cost $244m for solar mini-grids in rural Senegal, the Green Climate Fund provided $92.5m of finance. Based on the lifetime carbon emissions mitigated by that project and attributing it all to the GCF funding, the cost per tonne was $84, relative to a median cost of under $10 per tonne in the wider renewable energy generation portfolio. Although a fairly cost-effective project if viewed against the outcome of expanded energy access, the mitigation outcome of the project was clearly minor and only weakly synergistic with the energy access aim. Precisely tracking where mitigation outcomes of projects are minor and secondary is essential to ensuring that they do not attract a disproportionate amount of mitigation financing.

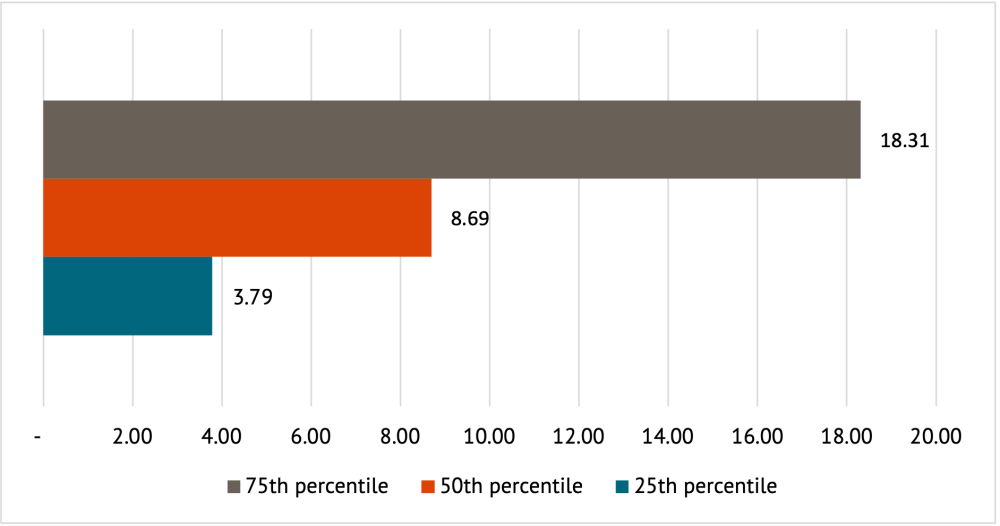

At a portfolio level, these impacts can be very substantial. In our paper, we show that if the combined $4.3bn CTF and GCF renewable energy portfolios' future climate effectiveness were equivalent to its current top quartile performance in that sector, for the same investment the increased climate gains would be the equivalent to avoiding emissions equal to the total for the UK in 2018.

Figure 1. Cost-effectiveness percentiles for CTF and GCF renewable energy projects weighted by fund financing ($ per tonne CO2 equivalent)

In the next phase of mitigation investment, a renewed focus on cost-effectiveness is necessary. Funds and development agencies should focus on cost-effectiveness in their use of climate finance to yield substantially more mitigation from the same investment, compared to business as usual.

Moving faster towards net zero at lower cost

As ministers and development agencies renew and extend their commitments on climate finance, they should require agencies to commit to provide the seven pieces of information we highlight in the box. The board members of these agencies will need to scrutinise this information and agency management will need to make certain that, if they are to ensure the most progress on climate and development, they focus on the effectiveness of these investments.

Finally, given the sums being invested and the paucity of good evaluations, and because all agencies will need to mainstream climate into their programmes, there is also a strong case for a new body. We call for a climate finance impact observatory to bring together evaluation of results, and to share lessons between bilateral and multilateral funders. Where that body should be housed is an open question, and we plan to say more in the coming weeks and months.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.

Image credit for social media/web: Adobe Stock