This week marks the International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women —a day to recognize violence against women (VAW) as a persistent and pervasive human rights and development issue. Since the start of the pandemic, I have been collaborating with Amber Peterman and other researchers to improve understanding of how pandemics and other crises increase the likelihood of violence against women, track a growing evidence base focused on rates of VAW in the COVID context, and propose solutions for how donor institutions and policymakers should respond to this shadow pandemic and prevent a return to a pre-COVID-19 “normal”—a state in which one in three women already experienced some form of violence. Here I summarize our efforts to date and outline plans to build on initial research.

Did VAW increase in past pandemics and crises?

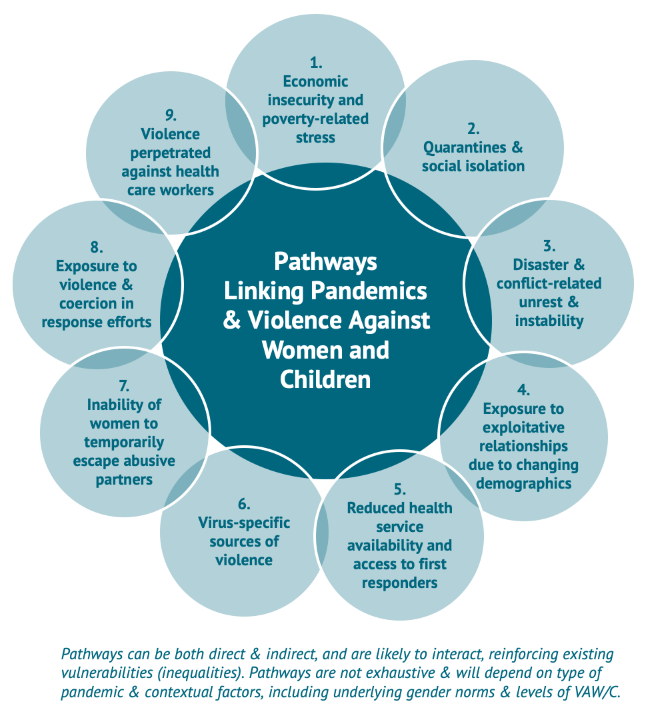

At the beginning of April, soon after COVID-19 had gone global in its reach and the WHO declared it a pandemic, media reports of intimate partner violence began to increase. But at that early stage, researchers had not yet had the chance to employ rigorous methods to confirm this reported uptick in violence, the reasons behind it, and the extent to which it was applicable across country contexts. In the interim, we drew upon historical data from other pandemics and public health emergencies—such as Ebola, Zika, SARS—and other crises. We traced pathways through which violence against women and children can increase in pandemics and other crisis contexts. As is reflected below, we ordered these roughly in terms of estimates of the population that may be affected by each pathway—anticipating that on the whole, more women and children will be present in households experiencing economic strain during a crisis like COVID-19 than, for example, the number of healthcare workers experiencing violence while at work, just based on relative population size.

These pathways to possible violence include stay-at-home orders and other lockdown measures that increase the amount of time potential victims of violence spend in close contact with potential perpetrators, as well as impose limitations on their ability to leave a violent situation, seek help from health, legal, or other frontline services, or turn to their friends and family for support or intervention. The pathways also account for the heightened financial strain that many households face as a result of economic downtown in pandemic contexts, causing mass unemployment and lost income, and resulting stress and tension leading to violence within households.

We also traced pathways related to school closures, seeing evidence from the Ebola outbreak of 2014 that out-of-school girls were more likely to spend time with older men and get pregnant, suggesting a potential increase in coerced, transactional sex. We see the risk of coerced sex increase as some humanitarian workers may take advantage of their position of power, whether distributing food or vaccines, to demand sex in exchange for these essential items. We see that frontline health workers, who are disproportionately women, may be increasingly subject to violence at the hands of those seeking medical attention or more broadly within their work contexts.

Do these historical pathways for increased VAW play out during COVID-19?

Of the 30 studies we have reviewed to date that measure violence against women, as well as children, during COVID-19, 13 studies (43 percent) show increases, in addition to 8 studies (27 percent) showing mixed findings, indicating increases in at least one measure. This group of studies is increasingly diverse in its geographic representation. We now have papers from a growing number of low- and middle-income countries, including Bangladesh, India, Mexico, Peru, and Uganda, in addition to those from the United States, the United Kingdom, Australia, and elsewhere.

With more evidence to draw upon, we can start to say with increased confidence based on rigorous data analysis that COVID-19 and associated policy response measures are driving increases in violence against women and children across contexts. And where mixed or decreasing trends appear, there is emerging evidence to suggest underreporting may in part account for results.

What should governments and donors do in response?

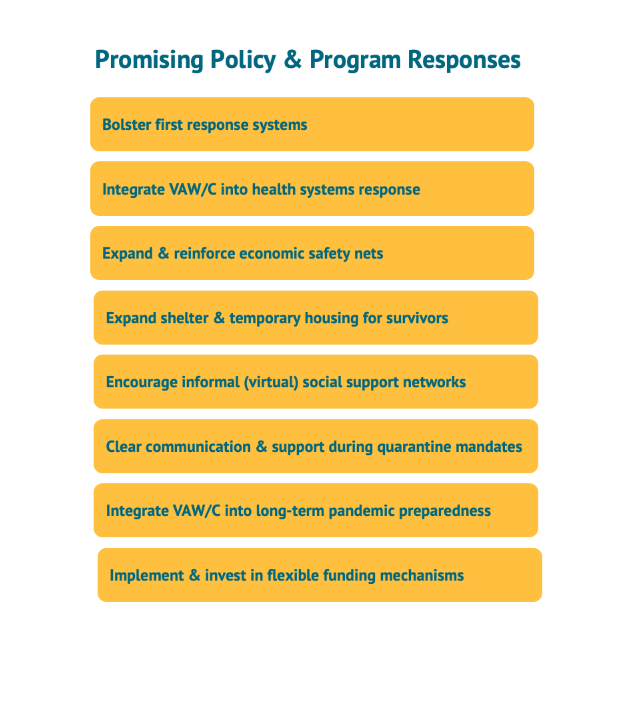

The second part of our initial working paper focused on potential policy responses: what national and subnational governments, as well as donor institutions and others, can do to mitigate risk of violence in the first place, and support survivors when it does occur.

Now, other organizations, including UNDP and UN Women, are working to document the policy responses that governments are announcing to respond to the pandemic. But there is still little evidence linking these responses with the research on “what works” to reduce violence and support survivors. The focus on “what works” has not yet measured up to the focus on just tracking whether violence is increasing or decreasing in light of COVID-19.

To complement the efforts of those tracking policy responses in real time, researchers with expertise on VAW now need to shift from asking “What’s happening” to “What should we do about it?” This shift in focus will support the efforts of policymakers and practitioners, and ensure their decisions are grounded in rigorous evidence.

Over the coming months, we will be working with the Lancet Commission on Gender-Based Violence and the Maltreatment of Young People, including researchers at the University of Miami, the UN University International Institute for Global Health, and the German Institute for Global and Area Studies, to explore the following questions:

- How do current policy responses (including those reflected in the UNDP tracker, as well as sub-national responses from select country contexts) align with evidence on “best practice” to reduce VAW and support survivors?

- What are the gaps to fill? What would be needed (in terms of government/donor financing, policy decision-making) to close those gaps?

From historical (pre-COVID-19) evidence, for example, evidence shows that cash transfers can play a role in easing the financial stresses within households leading to increased violence. With many governments mobilizing to provide these kinds of support in light of COVID, there will be opportunities to confirm this finding, as well as explore complementary interventions that can work at scale to reduce violence and support survivors.

To ensure we don’t risk returning to normal, donors and policymakers will need to increase the attention and investment they currently allocate to violence prevention and survivor support. And as researchers, we can contribute to ensuring any new or increased investments are grounded in reliable evidence. If you are a researcher with expertise on VAW and are interested in contributing to the project I mentioned above, please reach out to me at modonnell@cgdev.org.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.

Image credit for social media/web: International Monetary Fund/Raphael Alves