In 2017, the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) released a new Strategy for Accelerating HIV/AIDS Epidemic Control (2017-2020). The strategy identified 13 “priority high-burdened countries” where PEPFAR would focus on accelerating progress toward “epidemic control”—a point at which the annual number of new HIV infections falls below the number of annual deaths among HIV-positive individuals, implying a decrease in the total population living with HIV. (My colleague Mead Over defined this point as the “AIDS transition” in 2010.) Yet the strategy did not explicitly promise that these countries would receive additional funding, and the administration’s overall budget request for FY2018 constituted a decrease from prior levels. For outside observers, the extent and likelihood of consequent funding reallocations among PEPFAR countries—and the implications for the countries left off the prioritized list—remained open questions.

Now, with the release of PEPFAR’s FY2018 and FY2019 budget requests, we have our first signals: without congressional intervention, the “acceleration” strategy appears intended to involve meaningful reallocations of funding between countries. Of course, budget requests are not the final word; Congress has already rejected proposed budget cuts to PEPFAR for FY2018, for example, and is widely expected to do the same for FY2019. Nonetheless, the request offers some initial insight into the thinking of PEPFAR leadership—and what the “acceleration” strategy might mean in dollars and cents, at least if overall budget cuts actually came to pass.

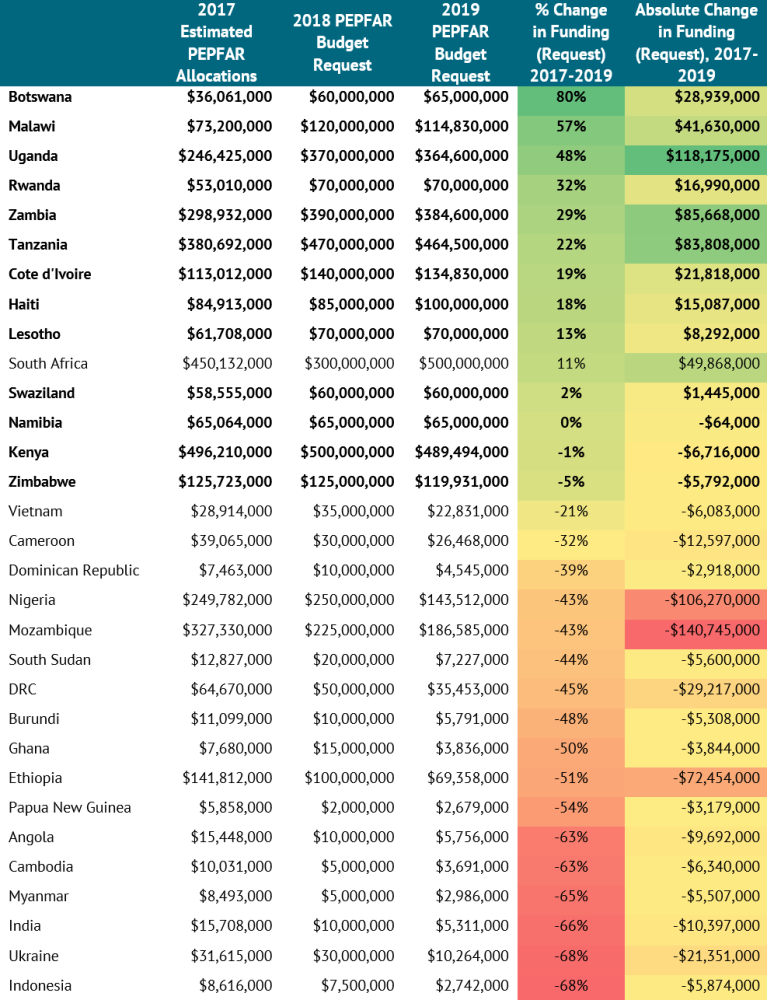

The table below shows indicative funding changes in PEPFAR’s bilateral country programs between FY2017 (estimated actuals) and FY2019 (budget request); the 13 PEPFAR “acceleration” countries are indicated in bold. With the singular exception of South Africa, designation as an “acceleration” country tracks perfectly to changes in the budget request over this period. The average “acceleration” country received an FY2019 budget request that is $31.5 million (24 percent) higher than its FY2017 allocation; requests for Namibia, Kenya, and Zimbabwe saw modest decreases, but generally maintained their high baseline levels.

Change in PEPFAR allocations, FY2017-2019, based on FY2018-2019 budget requests

Sources: State FY2019 Congressional Budget Justification; PEPFAR FY2018 Congressional Budget Justification Supplement.

Note: Totals were manually extracted from PDFs. Any errors in extraction are my own.

On the flip side, those countries left off the prioritized list received budget requests that would correspond to significant funding reductions if realized. Apart from South Africa (again), every non-prioritized country saw its PEPFAR budget request decrease by at least 20 percent relative to FY2017 actuals, and almost all by 40 percent or more. The average non-“acceleration” country saw a funding request corresponding to a 47 percent cut from FY2017 actuals—$23.7 million in absolute terms. In Nigeria and Mozambique, the budget request would imply a funding decrease of more than $100 million between FY2017 and FY2019.

Dramatic numbers aside, there are still several open questions:

-

As already discussed, the FY2017 funding levels are estimated actuals, while the FY2018 and FY2019 figures are just requests. PEPFAR ultimately received an additional $800 million (21 percent) above its budget request in the FY2018 Omnibus; much will depend on how PEPFAR distributes this additional funding across countries. Will it use the extra money to double down on its acceleration strategy, channeling even more additional funding toward the 13 priority countries? Will it reverse proposed cuts to the Global Fund or central programs? Or will it instead plug the holes in the bilateral country programs that would otherwise see cuts? Notably, although the overall PEPFAR budget request would represent a cut from FY2017 levels, the request for bilateral country programs is just barely budget positive, representing an increase of $11.8 million from the 2017 baseline. Even if the proposed PEPFAR cuts go unrealized (as most expect), the reallocation between countries might still take place.

-

Almost all PEPFAR money is channeled through contractors and grantees for specific programs versus directly to country governments as on-budget aid. Which programs and activities are getting scaled up—and are others on the chopping block? Cuts to technical assistance or training budgets might not be a big deal, but service delivery scale down could be more worrisome.

-

How do these potential PEPFAR cuts in some countries fit within the broader health financing environment? Is Global Fund support also declining, stable, or rising? What about domestic financing for HIV programs? Have PEPFAR leaders clearly and directly engaged country-level policymakers about possible consequences for service delivery?

I’m eagerly awaiting release of the next round of Country Operational Plans for further clarity on some of these points; I plan to update this table as soon as we have firm numbers. For now, however, it’s clear that money talks—and these figures demonstrate that PEPFAR’s “acceleration” strategy is a serious endeavor, backed up by the potential for large reallocations between its target countries.

Thanks to Erin Collinson, Sarah Rose, Amanda Glassman, Kalipso Chalkidou, Jen Kates, and Roxanne Oroxom for helpful comments.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.