Even before he took office, USAID Administrator Mark Green made clear his vision that the objective of foreign assistance “should be ending its need to exist.” While his predecessors espoused similar convictions, Administrator Green’s pledge to make “working itself out of a job” central to USAID’s approach has focused renewed attention on the question of how to responsibly and sustainably transition countries away from traditional, grant-based development assistance.

In recent months, USAID has been working diligently to craft its approach to “strategic transitions,” framing the principles it will follow, the benchmarks that will help inform transition decisions, and the programs and tools it can bring to bear. This Thursday, in a public discussion with the agency’s Advisory Committee on Voluntary Foreign Aid (ACVFA), USAID will outline its initial thinking about strategic transitions.*

Our recent paper, Working Itself Out of a Job: USAID and Smart Strategic Transitions, offers some advice to the agency as it charts the course ahead. Here are the main takeaways.

Lessons learned from past transitions

In formulating its approach to strategic transitions, USAID should draw on the following 10 lessons that emerge from its own history and that of other bilateral donors:

- Define transition goals, while recognizing broader US foreign policy objectives. Country transition plans should include both the development results and policy objectives USAID hopes to sustain as well as the actions required to achieve them, while taking into account the nature of the bilateral relationship.

- Consider options short of complete aid exit. While complete withdrawal may be prudent in some circumstances, USAID should have leeway to pursue other options—such as approaching transition on a sector-by-sector basis, maintaining a development representative in country to support limited programming, or funding programs from Washington or a regional mission.

- Recognize that coordination is crucial for effective transition planning. Close collaboration between USAID Washington and the field mission, as well as with other US government agencies, Congress, partner country stakeholders, implementing partners, and other bilateral and multilateral donors, is critical for transition success.

- Assess and mitigate risks to sustaining development results (i.e., know who will fill the vacuum). USAID should protect the value of its past investments and seek to sustain its results by collaboratively identifying priority areas to be advanced by local actors (or other donors) and considering how to prepare the designated actors to take on new managerial or financial responsibilities.

- Prioritize evaluation and costing of assistance activities that will be wound down. Critical to ensuring USAID-supported development results are sustained is understanding what (and whether) results have been achieved; costing exercises are similarly important for determining the appropriate actors—and the capacity of those actors—to take on additional obligations.

- Transparently monitor progress on the transition plan. Monitoring progress toward the agency’s goals of ensuring sustained results can help USAID understand whether a transition approach is on track, and, if not, explore opportunities to adjust plans.

- Ensure sufficient time for the above steps to occur. Sufficient time—at least 3-5 years—is necessary to meaningfully implement good transition practices; in contrast, overly compressed timelines can compromise US interests by hurting bilateral relations, undermining past development results, and/or leaving a void for competing powers to exploit.

- Balance clarity and flexibility in the transition strategy. While it is important for USAID to define and clearly communicate its objectives, timeline, plans, etc., there should be enough flexibility to accommodate new information (e.g., from consultations) and contextual shifts (e.g., natural disasters, economic shocks) that emerge during the transition process.

- Plan for mission staffing adjustments as part of the transition. USAID should recognize that transitions may require specific managerial skills and expertise that may not already exist within all missions; in addition, any staff downsizing must be sensitive to the need to preserve important relationships throughout the transition and support local staff in moving to new employment.

- Learn and capture lessons. USAID should expand knowledge around common challenges and pitfalls by building into each transition process opportunities for real-time learning through experience sharing, as well as formal ex-post evaluation.

The pros and cons of using quantitative benchmarks to identify countries for transition—and an idea for how to do it

USAID has signaled interest in using quantitative benchmarks to evaluate a country’s readiness for transition. Using quantitative metrics ensures evidence is brought to bear on an important determination and can lend greater transparency, credibility, and accountability to the process. However, quantitative indicators will never provide a comprehensive picture of a country’s transition readiness, nor will they easily quantify broader US foreign policy and national security interests. Furthermore, data often carry some imprecision and are reported with a time lag. For these and other reasons, it is important that USAID not adopt a rigid or overly prescriptive interpretation of the quantitative criteria it develops.

We recommend a two-stage assessment for determining which countries might be ready for transition. The first stage would employ quantitative indicators to measure factors such as country need, fragility, good governance, business and economic environment, and financing capacity. The set of countries that show high performance across these measures would be analyzed further in the second-stage analysis that would employ both quantitative and qualitative information to assess whether national-level performance masks important subnational, gender-based, or other disparities, as well as a wider range of policy, institutional, and capacity issues most relevant to the sectors USAID funds.

Defining US engagement through the transition process and beyond

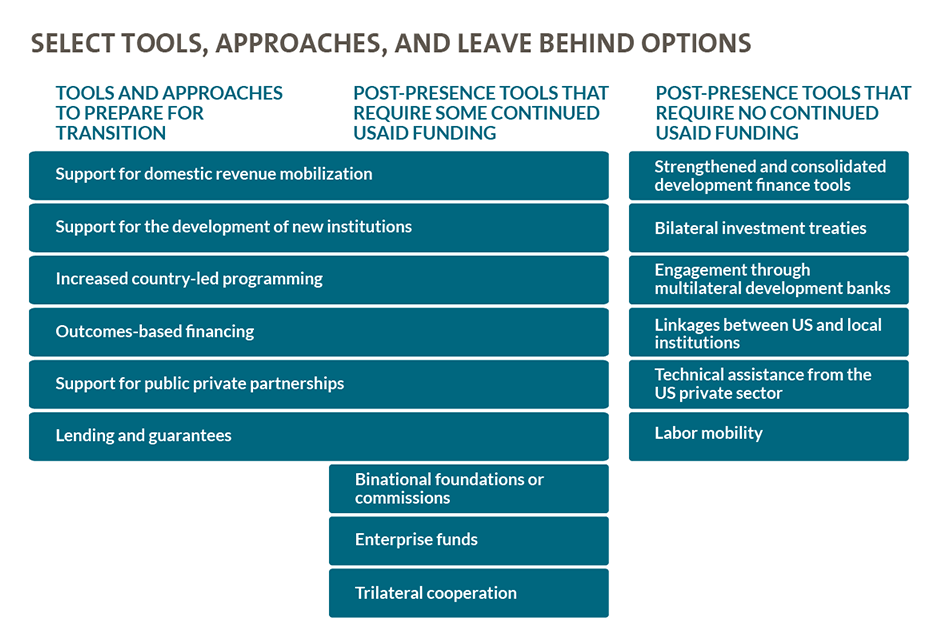

As USAID seeks to define a path for sustained partnership with transitioning countries, the agency should explore a full range of tools, some of which go beyond traditional, grant-based assistance.

The avenues of engagement that USAID pursues and the legacy structures it seeks to put in place will vary by country, depending on the nature of the agency’s existing investments, capacity and financing gaps in the partner country, the priorities of the partner country government, and the character of the broader bilateral relationship, among other things.

*Sarah Rose participated in an ACVFA working group focused on strategic transitions.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.