Recommended

When Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, was founded in 2001, it logically targeted its support to the poorest countries—with GNI per capita under a pre-defined eligibility threshold—that also had the highest shares of the world’s undervaccinated children. Fast-forward almost 25 years, and the situation has changed significantly. Today, middle-income countries (MICs)—including former Gavi-eligible and never Gavi-eligible countries—are increasingly becoming ground-zero for undervaccination challenges.

While Gavi offers modest financial and technical support to select MICs, including through its MICs Approach, this support remains ad-hoc and insufficient to meaningfully address the scale and scope of the challenges they face.

As it crafts its next strategy for the 2026–2030 period (known as “Gavi 6.0”), Gavi should reassess its engagement with MICs, which will be critical to continue to advance its core mission and contribute to global vaccination goals.

In a new policy paper released today, we offer recommendations for Gavi to operationalize broader engagement with MICs in its next strategic period—and beyond. Acknowledging the complex challenges that MICs face alongside the reality of budgetary headwinds, we argue that Gavi should focus on opportunities that best leverage its comparative advantage in market shaping to drive maximum impact for global vaccination efforts within limited resources.

Why MICs are becoming “ground zero” for global undervaccination

First, non-Gavi MICs—including former Gavi-eligible and never Gavi-eligible countries—now account for an increasingly large proportion of the world’s undervaccinated population. Some larger MICs that have transitioned from Gavi still contain significant pockets of undervaccination since Gavi’s eligibility and transition policy is based on income rather than programmatic readiness or coverage rates. And some formerly eligible MICs have seen coverage rates for certain vaccines erode as they have transitioned to fully self-financing. Further, coverage for routine immunization remains unacceptably low in some never Gavi-eligible MICs. Most notably, a growing proportion of zero-dose children live in MICs, with nearly a quarter of the global population in just five countries that do not meet Gavi’s standard eligibility criteria: India, Angola, Indonesia, the Philippines, and Brazil.

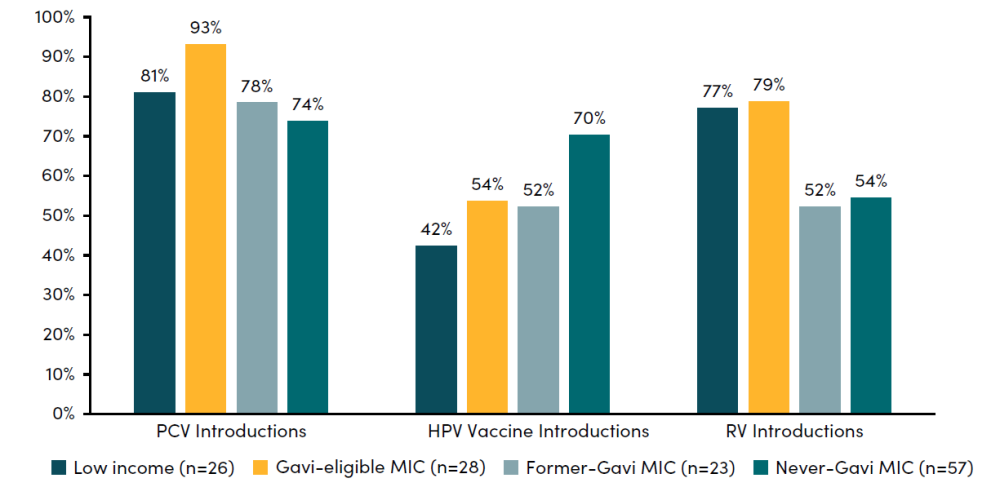

Second, MICs are getting less for more with their immunization expenditure. Notably, many non-Gavi MICs have not introduced newer WHO-recommended vaccines, such as the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV), human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine, and rotavirus vaccine (RV) due in large part to affordability and cost-effectiveness challenges. Non-Gavi countries sometimes face higher vaccine prices than those that are made available to Gavi-eligible peers, which is a key driver of slow introduction.

Figure 1. Introductions of new or underutilized vaccines by country income group and Gavi eligibility status

Note: Data reflect introductions into national immunization programs as of February 20, 2024, using FY 2024 World Bank income groups and 2024 Gavi eligibility. Sources: International Vaccine Access Center, “VIEW-hub,” Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, last accessed February 20, 2024, https://view-hub.org/; “World Bank Country and Lending Groups,” World Bank, last accessed March 22, 2024, https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups; “Eligibility,” Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, last accessed March 22, 2024, https://www.gavi.org/types-support/sustainability/eligibility.

Lastly, MICs were hit particularly hard by pandemic-related disruptions to routine immunization systems. Even while recent coverage data indicates rebounding, many MICs are witnessing acute budgetary pressures amidst fiscal tightening. Notably, government expenditure for health is projected to stagnate in 34 percent (27/80) and contract in 25 percent (20/80) of non-Gavi MICs, respectively. These realities could have implications for future spending by self-financing MICs on essential health services, including immunization.

Where Gavi’s current support to MICs falls short

Gavi provides a range of support modalities to countries that are not eligible for traditional support in the form of targeted financing, technical assistance, and access to sustainable pricing for newer vaccines. For example, Gavi’s MICs Approach aims to prevent backsliding in vaccine coverage and support the introduction of key missing vaccines in 46 former and never Gavi-eligible countries, including some MICs that are classified as fragile and conflict-affected. Gavi has also worked closely with UNICEF Supply Division to operationalize an innovative financing mechanism and facilitate sustainable prices for vaccines like PCV, HPV vaccine, and RV.

The MICs Approach provides $300 million in targeted “catalytic” funding that is tailored to country-specific needs—a meaningful but relatively modest amount. COVID-19 delayed operationalization of Gavi’s programmatic support to MICs, which means there is little information to assess progress and impact under the MICs Approach to date. Still, the support remains small-scale and insufficient to address the multifaceted and complex challenges MICs face.

How Gavi can operationalize broader engagement with MICs

We offer three recommendations for Gavi to operationalize broader engagement with MICs in its next strategic period, “Gavi 6.0,” and beyond. We urge Gavi’s board to empower the Secretariat with the requisite authorities, resources, and mandate to enable the successful operationalization of these recommendations.

1. For newer and costlier vaccines, facilitate opt-in framework agreements with centrally negotiated tiered pricing for an expanded cohort of MICs. Gavi should dramatically expand existing efforts by working with UNICEF to negotiate tiered pricing framework agreements with manufacturers. These framework agreements should be available to all MICs on an opt-in basis, with priority placed upon the newest and costliest vaccines. The use of tiered pricing—differential pricing offered to different categories of countries based on ability to pay—may attract additional manufacturers who would oppose expanding the Gavi preferential prices to most or all MICs, which would undercut existing sales and erode profit margins in those markets. Given the lower uptake of newer vaccines across Gavi-ineligible MICs, there is a meaningful win-win opportunity: manufacturers can attain higher volumes and reach additional markets at profitable prices, while also offering locally affordable prices to countries that have not yet introduced a new vaccine.

2. For future vaccines, facilitate opt-in market entry framework agreements with centrally negotiated tiered pricing for an expanded cohort of MICs. Building on the proposed framework agreements for newer vaccines (see #1), Gavi is uniquely positioned to lead a more proactive approach for future vaccines to market entry for all MICs. Specifically, we recommend that Gavi facilitate opt-in market entry agreements with centrally negotiated tiered pricing for an expanded cohort of MICs. These framework agreements could help facilitate broad, equitable, and affordable access on a far more rapid timeline.

3. Support a global Coordinating Hub for the Immunization Innovation Agenda (CHIIA). Gavi should consider an expanded role as founder and host of a new Coordinating Hub for the Immunization Innovation Agenda, broadly targeting vaccine innovations that would be helpful or in-demand across national income levels. The proposed Hub would require only relatively modest Secretariat resources and would be supported by Gavi alongside other partners like the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI). It would welcome membership from all countries but focus on the collective needs of the broad low- and middle-income country cohort, helping to cement Gavi’s role as an advocate and facilitator of the global vaccine agenda.

The global landscape of undervaccination will likely look vastly different in the post-Sustainable Development Goals era. Gavi’s board and leadership should use the next five-year strategic period to operationalize broader engagement with MICs and advance global vaccination goals, leveraging Gavi’s comparative advantage and staying realistic within constrained resources.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.

Image credit for social media/web: IMF/ Raphael Alves