Recommended

Health aid in its current form is fragmented, burdensome, and lacks country ownership in how it is allocated. COVID-19 stalled or set-back progress on health gains; there are tightening fiscal pressures on health for countries and donors; and there are increasing calls to rebalance power dynamics in global health. Gavi’s next strategic period, known as “Gavi 6.0”, offers an opportunity to redefine the Alliance’s financing modalities and respond to the challenges for the future of global health; particularly as it leads into the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals deadline.

This CGD Note outlines a proposal for a New Compact between Gavi and partner countries. We outline a package of policy shifts for Gavi to consider, in line with the core approach of prioritising country ownership and financing of the highest priority vaccines while health aid is provided at the margin. The set of related policy shifts centre on reworking health service financing, and are complemented by adapting pooled procurement, strengthening market shaping, ensuring comprehensive coverage, and advancing donor harmonisation. As part of this, we offer next steps for how Gavi can act on transitioning to the New Compact approach.

Challenges facing Gavi and its partner countries

At a macro-level, countries continue to recover from the pandemic and respond to an evolving global landscape—growing conflict and fragility, the polycrisis involving climate change, and deteriorating macroeconomic conditions. Public budgets are under pressure due to increasing demands, economic slowdowns, and increased debt repaymentsdue to higher interest rates. Moreover, ministries of health in Gavi-eligible countries face their own challenges: evolving demands from health systems, an increasingly complex burden of disease, vaccine innovation that requires new immunisation platforms, and a fragmented aid ecosystem which works against efficient and joined up policymaking at the national level. This challenging political and economic context make it difficult for health aid to be delivered effectively.

Development assistance can help fill important gaps in health service delivery, but there are several key issues with current practices that undermine country efforts towards effective, sustainable health systems. These have been described more completely in previous CGD papers, but in brief include: funding volatility, aid fragmentation, the displacement of domestic finance, ineffective prioritization, the lack of transition planning, and the lack of country ownership.

Gavi itself faces multiple related challenges: funders with new priorities (e.g., a shift from acute to chronic disease financing, tightening fiscal space post-COVID-19, redirecting finances to address increasing global threats outside of health); expensive new vaccine technologies that may require life-course approaches to immunisation; and a client base which faces limited opportunities for strong and sustained economic growth. New strategies for addressing the outlined challenges for global development and health financing are critical to maintain social and economic progress. Of note, the Future of Global Health Initiatives process had proposed the need for significant shifts in current operating models towards more sustainable, country-centred efforts to delivering universal health coverage, especially for Global Health Initiatives (GHI) such as Gavi. As a result of this, the Lusaka Agenda outlined key shifts that need to be accelerated to shape the evolution of GHIs. CGD has also proposed policy recommendations for Gavi to advance equitable and sustainable immunisation in an evolving global landscape and rethink countries’ transition trajectories and eligibility prospects, given the fiscal challenges countries face.

Despite demonstrating its ability to improve health outcomes through leveraging vaccine introductions, coverage, and country eligibility, Gavi’s approach needs adapting to meet the demands of the challenges mentioned above. Gavi’s current model includes co-financing policy which incentivises countries to incrementally increase domestic financing for immunisation, setting countries on a time-bound path to transition away from Gavi support. Under the proposed recommendations for global initiatives, Gavi would need to rethink this model of health service financing to drive improvements in equitable coverage and long-term systems strengthening in countries. Gavi is also guided by health system and immunisation policy that could adapt to better realise Gavi’s principles of country-driven, equity-focused, tailored-to-context health system strengthening with additive and complementary support for countries

A New Compact for financing health services

CGD has previously outlined the possibility of a New Compact to address current global health challenges comprising three pillars:

- Locally led evidence-informed prioritisation. Country institutions are supported to set health priorities, drawing on relevant available evidence.

- Domestic-first resource allocation. Country ownership, including financing, of the core package of high priority services.

- Consolidated supplementary aid. Donors work together and with country leaders to design a top-up package, both in terms of additional health services and other cross-cutting support.

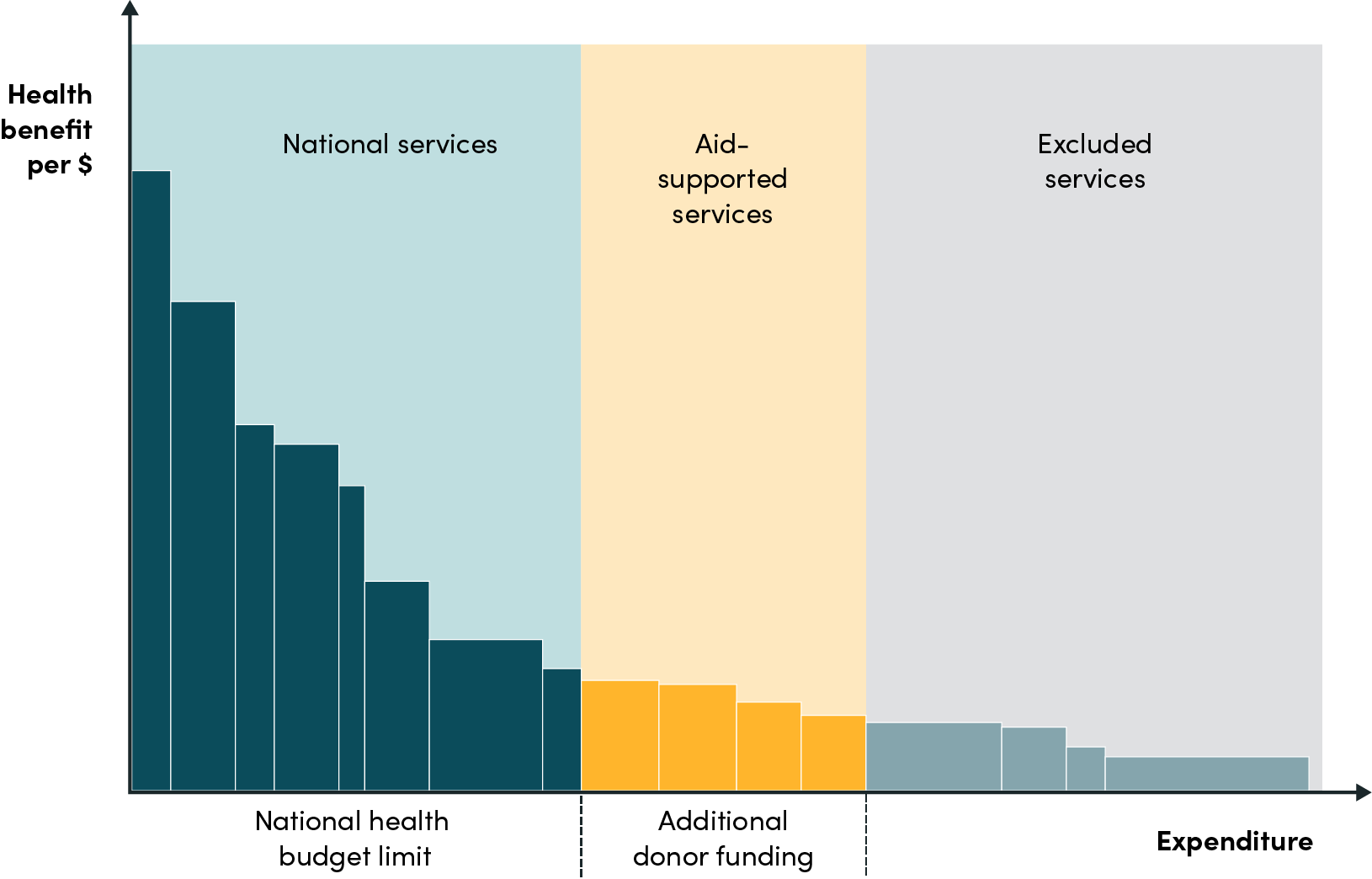

In the New Compact domestic finances should support essential health services and health aid should primarily be used to expand the package of affordable services at the margin (see Figure 1). Instead of targeting the most cost-effective interventions, donors should support countries to have strong and effective prioritisation processes and direct any additional financial support for health services to those that would otherwise not be covered by domestic funds.

Figure 1. Illustration of prioritised health benefits package with aid investment at the margin

This New Compact would address challenges to health aid mentioned above, and encourage better planning and prioritisation by countries and donors, leading to more overall health for the money. As countries’ health financing improves, health aid focused at the margin is naturally crowded out, offering a seamless aid exit strategy for thriving countries and ensuring the sustainability of financing for countries that continue to need support. Perhaps most fundamentally, the approach empowers national decisionmakers and national policy processes.

How a New Compact between Gavi and partner countries could work

While the above concept frames a New Compact at the country level, with a single country and multiple donors. In this brief we focus on outlining a corresponding set of policy shifts but from a single donor perspective, in this case Gavi. Here, the New Compact would prioritise country delivery and financing of the highest priority vaccination programmes, as determined through a country led evidence-informed prioritisation process (see Figure 2 for an illustration of cost-effectiveness-based prioritisation). Alongside, Gavi would provide tailored technical assistance to ensure high coverage and quality, and adapt pooled procurement platforms to sustain value for money and consistency of supply.

Figure 2. Illustration of an example of vaccine prioritisation and financing based on cost-effectiveness

Data sources: DALYs averted per 1000 vaccinated individuals in LMICs between 2000 and 2030; total vaccinated individuals per country; and total costs for Gavi and country financing arrangements were gathered from Gavi’s website from decision letters and partnership agreements for each country. Note while this figure draws on real data, it is for illustration only, since prioritisation would need to be done at the country level.

Building on the three principles underpinning the New Compact concept, outlined above, Figure 3 summarises a set of policy shifts grouped into five themes that Gavi and partner countries could pursue. These are ‘building blocks’, where the core of the New Compact is the top block; Rework Health Service Financing. Ensuring comprehensive coverage, advancing donor harmonisation, adapting pooled procurement, and strengthening market shaping are complementary policy shifts that are not strictly necessary to implement the New Compact financing changes, but would support effective implementation and mitigate potential risks. The policy shifts are described in more detail—including their specific benefits, challenges, and risks—in Appendix 1.

Rework health service financing. The core element of the New Compact is to reorganise vaccine financing by focusing country ownership of the most-cost-effective, high-priority vaccines and shifting Gavi financing towards the next most cost-effective services, including new vaccine introductions, as well as other supporting activities. Countries would progressively take over funding responsibilities informed by local priority-setting processes, drawing on cost-effectiveness and other kinds of evidence, according to their preferences. This shift is would be a natural extension to Gavi’s Full Portfolio Planning (FPP) model, adopted as part of the Gavi 5.0 strategy, which aims to ensure that Gavi support is catalytic, built upon country co-financing commitments, and aligned with national immunisation priorities. More specifically, countries would have firmly embedded financing arrangements for core services while Gavi would finance or co-finance marginally cost-effective services. Gavi could offer technical assistance for this transition, including strengthening evidence-to-policy processes, integration of vaccine policy functions with the wider health system and support to improve public financial management. To complement increased domestic financing, Gavi resources may be redirected to other priorities to strengthen country health systems. These savings can be reinvested domestically, allowing for the inclusion of previously excluded services, expanding the scope of protection.

Ensure comprehensive coverage. Equity is an organising principle for Gavi and a key feature of the New Compact. Countries and Gavi might agree that implementing high coverage immunisation, including underserved or hard to reach populations, is a priority and Gavi could provide technical and political assistance to countries throughout the New Compact transition for achieving universal coverage, including identifying, prioritising, and monitoring marginalised communities. Where necessary, Gavi could support targeted vertical vaccination to populations which public services are unable to reach (e.g., refugees).

Advance donor harmonisation. The New Compact emphasises countries taking the lead in shaping their health system's development, challenging the donor community to adjust. To address duplication and conflicts among donors, aligning funding cycles and streamlining requirements could reduce burden on countries. Country-level multi-donor committees could enhance coordination locally. While Gavi alone cannot implement this agenda, it can play a prominent role due to its credibility and importance in the global health landscape. Gavi’s alignment to country-level progress and leadership would benefit from countries clearly communicating local demands and funding cycles.

Adapt pooled procurement. Under the current model, countries benefit from Gavi’s buying power and procurement expertise to access fair prices and reliable vaccine supply. New procurement models may be needed to sustain these benefits. This could mean an adaptation of Gavi’s current procurement practices enabling the use of recipient country commitments in addition to donor funds to facilitate pooled procurement or the nascent initiative from Africa Center for Disease Control and Prevention could step in to support countries with vaccine procurement. Notably, adapted Gavi procurement mechanisms could also mean that former or never-Gavi eligible countries could benefit widening the support Gavi can provide.

Strengthen market shaping. The New Compact maintains and potentially creates more space for Gavi to step up its role in market shaping and ensure sufficient resourcing for its Vaccine Investment Strategy. As existing cost-effective vaccines transition to country responsibility, Gavi may focus more on ensuring access to innovative vaccines, for example through carefully designed “pull” financing such as value-based Advance Market Commitments (AMCs). However, Gavi's role in innovation must align with country priorities and actions. Countries could clearly communicate their national needs and readiness for innovative technologies and design conducive regulatory environments to support their uptake.

Figure 3. Policy shifts from Gavi and partner countries if adopting the New Compact

Potential benefits – Why do this?

The New Compact has the potential to create space for country-led development of comprehensive immunisation systems fit for the long-term. It aligns with Gavi’s key priorities and may yield various benefits in line with current and upcoming organisational strategy. First, the centring of country ownership and systems—including evidence-informed prioritisation and financial management—creates space for institutional strengthening while expanding immunisation programmes. In other words, it allows a dual focus on both short and long-term health goals. Improved prioritisation should result in more health for the money. Similarly, a reduced role for aid in core services should ameliorate risks of transition out of Gavi support. Second, with core interventions being financed through domestic avenues, the approach potentially frees up resources and opportunities for Gavi to accelerate new vaccine introductions, further support health system strengthening of new and existing architecture, step-up market shaping activities and expand a lighter footprint of services to a wider base of countries. Third, the complementary shifts towards adapted pooled procurement and strengthened market shaping are less resource intensive to scale than vaccine financing and could allow Gavi to serve a much wider base of partner countries than it currently does. This could include countries not currently eligible for Gavi support. Notably these are also areas where Gavi has a clear advantage in being able to fulfil a function that countries are less able to.

Challenges and risks

While there are significant potential benefits to the policy reforms outlined here, there are important challenges and risks. Perhaps the most salient is the risk that transitioning high-value vaccines out of direct Gavi financing results in reduced health outcomes or immunisation of at-risk populations and vulnerable groups in particular. This could manifest in multiple ways from inadequate budgeting or political will, to supply chain interruption, to delivery failures. Capabilities of country-level institutions and processes for evidence informed priority-setting will vary and it may be a challenge to correctly know which vaccines are most cost-effective where. Moreover, it will be practically challenging for Gavi to make bespoke agreements based on this information with each partner country. While many challenges will be technical or operational, some could arise as the result of differences in priorities between Gavi and its partner countries and deliberate policy decisions. For example, countries may decide to introduce an out-of-pocket payment for vaccines, ameliorating budget impact and averting trade-offs with other public services, but likely reducing uptake in lower-income groups. Lastly, Gavi relies on narratives of the provision of highly cost-effective services for advocacy and fundraising. With a different model for impact more nuanced narratives will need to be developed.

Next steps

Stakeholders including decision-makers in low- and middle-income countries, academics, researchers, global health donors, and multilateral organisations all have a role to play in realising a New Compact for global health financing. For Gavi specifically, we identify the following potential areas for action.

1. Develop a New Compact policy framework

This brief does not offer an implementable policy framework and further work is needed to develop policy specifics with close consultation between Gavi and partner countries. A policy framework would need to articulate how country-led evidence-informed prioritisation would inform vaccine financing and be clear about links to current frameworks—such as the Vaccine Funding Guidelines and the health systems and immunisation strengthening policy—to ensure that sufficient technical assistance and other kinds of support beyond vaccine financing are available.

2. Pilot financing reforms with partner countries

Following a process of engagement with partner countries, Gavi could pilot a New Compact approach with a small number of interested counties. Countries nearing transition away from Gavi support and with strong existing functions for evidence-informed priority-setting are likely to be good candidates. This will require detailed jointly owned transition plans, tailored technical assistance and perhaps temporary arrangements for procurement support. An outline of the potential stages of the pilot process is in Figure 4. Success of the pilot is likely to be assessed through an adapted version of the evaluation framework in Gavi’s Vaccine Investment Strategy and in terms of stakeholder perceptions

Figure 4. Illustrative stages towards piloting financing transition with partner countries

3. Refine strategies for multilateral approaches to support vaccine procurement and catalyse new vaccine innovation

To secure the benefit of pooled procurement under the New Compact, Gavi may explore flexible options for continued participation to pooled procurement for countries after transition or Gavi-ineligible countries. Notably, middle-income countries (MICs) and target populations for innovative vaccines (i.e., adolescents or adults for diseases such as malaria and tuberculosis), may benefit from Gavi support. Gavi’s MICs Approach could particularly benefit by using the New Compact as a mechanism for sustainable vaccine introductions and prevention of backsliding in vaccine coverage. Alternatively, Gavi may consider supporting regional pooled purchasing consortia such as the one led by Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, linking plans to the nascent African Vaccine Manufacturing Accelerator (AVMA).

4. Champion rebalancing country-donor dynamics in multilateral forums and high-level political engagement

Policy reform of the kind outlined in this brief would require significant operational change for Gavi. However, for systemic change, the response to calls from countries to rebalance power dynamics and rework complex financing arrangements must entail coordinated action from donors. As a prominent multilateral Global Health Initiative, with broad-based support and a strong reputation for effective global health leadership, Gavi has the opportunity to address its own ways of working while also championing and leading wider donor harmonisation efforts.

Appendix 1. Summary of policy shifts for a New Compact Between Gavi and partner countries

|

Policy Shift |

Policy Specifics |

Benefits |

Challenges and Risks* |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Gavi |

Partner Country |

|

|

|

Rework health service financing |

*Agree new co-financing policies to support country-led domestic financing of the most cost-effective or high-priority interventions. *Provide technical assistance to support both domestically- and Gavi-financed vaccines. *Provide additional financing and technical assistance for new vaccine introductions.

|

*Adopt or strengthen an evidence-informed priority-setting processes to define priority national health services. *Progressively assume a greater or full share of financing and delivery of the highest priority vaccines.

|

*Domestic financing for high value vaccines ensures consistent, sustainable support for key vaccination programmes. *Progressive transition toward country-level responsibility. *Locally driven approach to priority setting based on context-specific challenges. *Improved coordination and collaboration in health system strengthening between Gavi and country. |

*Ineffective implementation or insufficient financing from governments, leaves populations under vaccinated and at risk. *Countries choose to implement with some degree of out-of-pocket payment, potentially resulting in reduced uptake particularly in low-income or marginalised groups. *Public financing for vaccines is redirected from other important public services, including non-health services. *Limited institutional capability could mean inadequate planning for the financing transition leads to temporary gaps in vaccination *Pooled procurement is disrupted, resulting in high vaccination costs. |

|

Adapt pooled procurement |

*Reform existing platforms or consider supporting new platforms for pooled procurement to enable domestic financing *Consider inclusion of former or never-Gavi eligible countries to maintain or even increase the pool |

* Reform to address legal, institutional, and administrative barriers and inefficiencies to participate in pooled procurement. |

*Partner countries have access to reliable supply of key vaccines at fair prices. *Former-Gavi eligible countries/ never Gavi eligible countries could potentially also benefit from adapted platforms for pooled procurement. *Reliable demand is established for manufacturers, promoting market efficiency and incentivising innovation. |

*Pooled procurement fails as wealthier countries cut sweetheart deals with industry. |

|

Strengthen market shaping |

*Step up role in incentivising vaccine innovation by creating clear value-based market demand commitments. * Increase support the creation of enabling environments for new vaccine introductions e.g. through supporting regulatory reform |

*Clearly communicate national needs and readiness to uptake innovative technologies. *Consider designing a conducive regulatory environment to support uptake of innovative technologies. |

*Domestic financing of high priority vaccines leads to increased budgetary space for new vaccines in Gavi’s Vaccine Investment Strategy. *Clearer roles for country financing of essential vaccines and multilateral incentivisation of innovation. *Provision of clear return on innovation investment for manufacturers |

*Multilateral procurement facilitation mechanisms (either through Africa CDC or Gavi and its core partners) may struggle with the complexity of securing commitments from partner countries. *Investing in innovation is, in some sense, a gamble on future gains, with an opportunity cost of higher coverage with existing effective technologies. |

|

Ensure comprehensive coverage |

* Enhance technical assistance to ensure continued progress towards reaching zero dose populations (for both domestically- and Gavi-financed vaccines). |

*Develop or strengthen systems for financing and implementing high coverage immunisation with vaccines being transitioned from Gavi to domestic financing, including underserved or hard to reach populations. |

*Equitable prioritisation through the new compact. *Strengthened links between underserved populations and the public health system. *Gavi financing can be better targeted to contexts outside the country's responsibility or control (e.g., refugees or displaced persons). |

*Given the high level of need in marginalised communities, it may be challenging for Gavi to develop robust and defensible prioritisation procedures. *Countries may be unable to incorporate marginalised communities in political decision making and economic development and this inability may be persistent and long-lasting. |

|

Advance donor harmonisation |

* Lead other donors to align funding cycles, unify application and continued reporting requirements to reduce burden on countries, and create country-level multi-donor coordinating committees. |

*Clearly communicate local demands and funding cycles to enable Gavi’s alignment to country-level progress and leadership |

*Better coordinated and nationally relevant financial support for countries. |

*High level leadership from donors is absent, resulting in operational inefficiencies - many meetings but few actual changes. |

*Challenges or risks associated with the policies outlined in this table, which may not be unique to the New Compact.

This note draws on an in-progress policy paper led by Alec Morton, Jamaica Briones, Pete Baker, and Tom Drake. Thanks also to Javier Guzman, Janeen Madan Keller, Morgan Pincombe, and Orin Levine for comments.

Rights & Permissions

You may use and disseminate CGD’s publications under these conditions.