The UN reckons that more than 11 million Syrians have fled their homes, nearly 5 million of whom are now in Turkey, Lebanon, Jordan, and Iraq. More broadly, UNHCR estimates that there are about 65 million forcibly displaced people around the world, including more than 21 million refugees. That’s about the same as the population of England and Wales, or the population of Italy.

We all want to fix this problem. Affected families endure a double burden of poverty and uncertainty. Displacement can threaten regional stability. And it fuels divisive politics in countries that perceive themselves to be at risk of large inflows of refugees. So why is displacement still a tough, unchecked challenge?

One major reason is that displacement isn’t—yet—a development problem.

That sounds odd. There are tens of millions of people on the ‘displacement caseload.’ Moving people off the caseload is incredibly slow. And people stay displaced for more than 10 years on average: we need sustainable solutions, not short-term fixes. So it feels like displacement—a big, slow-moving, large-scale, long-term problem—is clearly a development issue.

But displacement falls between the cracks of how we traditionally tackle these challenges. The usual toolkit of cheap financing (like World Bank IDA lending) and technical assistance focuses on lower-income countries. That’s a bad match for a caseload that is now mainly in middle-income states. As a result, we’ve relied on annual humanitarian appeals to tackle displacement instead of the long-term development finance that is a better match for these long-term problems.

One of CGD’s newest work streams, a study group co-convened with the International Rescue Committee, is finding ways to address the mismatch.

Why do we need a toolkit of longer-term instruments and programmes to deal with displacement?

Reason #1: It’s big and slow

Sixty-five million is a big number.

It helps to frame the pieces of this challenge to say that the number of asylum seekers is a population roughly the size of Puerto Rico’s. The number of refugees is a population roughly the size of Sri Lanka’s. The largest share of displacement is actually families who cannot leave their countries—the number of IDPs is roughly the population of the Ukraine.

Yet the pathways to shrink these numbers and get people into “durable solutions”—resettlement, repatriation, or local integration—are painfully slow. In 2014, there were about 95,000 successful resettlement applications, most of which were accepted, with another 127,000 repatriated to their home countries. (Official statistics aren’t kept for local integration, which can lead to naturalization.)

So available figures suggest roughly 1 in 300 displaced people had a durable solution. At that rate, it would take well over 200 years to move everyone off the caseload—and only if no new people were displaced.

Reason #2: It’s long-term

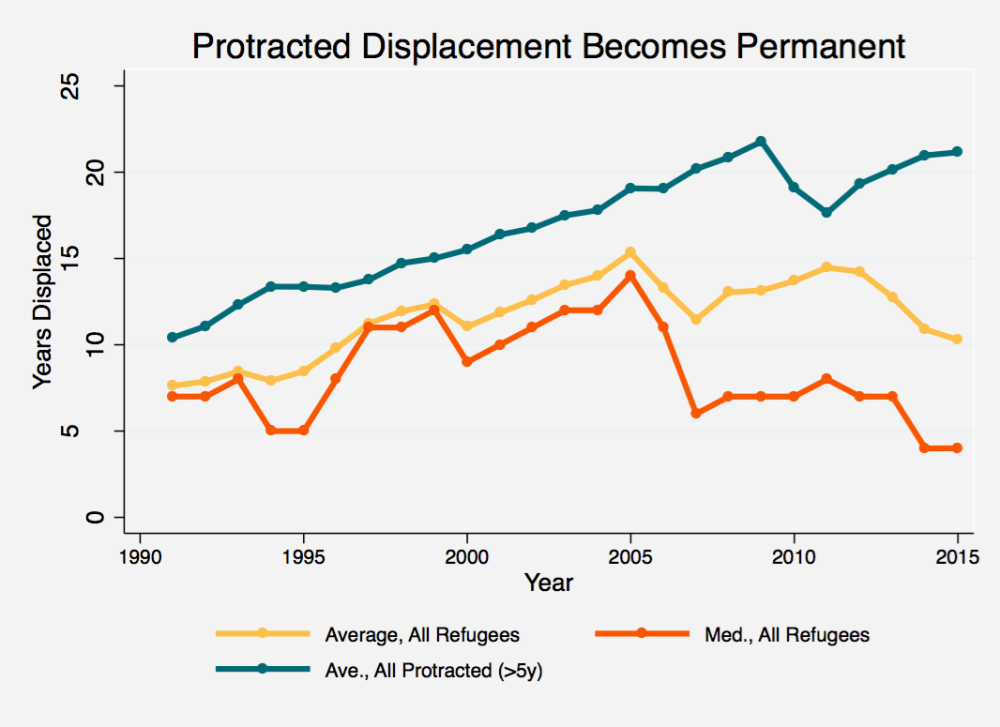

These figures help get a fix on the problem, but ‘headcount’ statistics alone aren’t very helpful. It’s total time displaced, not only the number of displaced, that matters. People have often claimed that the average duration of refugee displacement is about 17 years. That turns out to be a zombie statistic, accepted mainly by dint of repetition.

The truth is more complicated. Some top-shelf new analysis by Xavier Devictor and Quy-Toan Do, two World Bank economists, applies some minimal assumptions to UNHCR’s data to back out what durations look like.

Source: Devictor, Xavier, and Quy-Toan Do. "How many years have refugees been in exile?." World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 7810 (2016). CGD Analysis. Data requested from authors.

The results suggest that the average time (the yellow line) for refugee displacement peaked in 2005, and has declined since then to about a decade. But it also corroborates the intuition that displacement is driven by large ‘episodes,’ some of which create groups that remain displaced without an end in sight. The teal line is the average time of displacement among people who have been displaced for five years or longer.

The Syrian crisis helps illustrate both trends, and the fact that shorter average lengths of displacement don’t always reflect progress. The recent large outflow of Syrian refugees (now nearly a quarter of the world’s refugee population) has pulled down the median and mean length of displacement because they have not been displaced for very long. But even in optimistic scenarios, these families are likely join the ranks of those living in protracted displacement for many years to come.

Reason #3: It’s mismatched

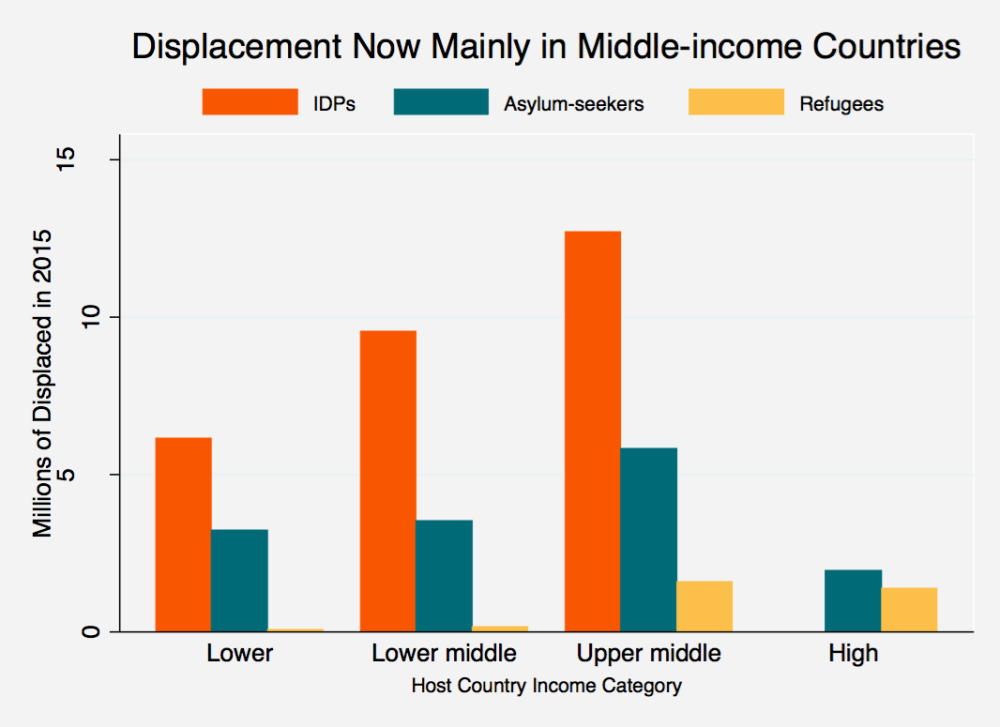

Another misconception is that displacement is a ‘poor-country problem.’

This chart shows the different categories of displaced people based on the income category of the countries they’re living in, using 2016 World Bank income classifications. Most of the caseload is in the world’s middle-income countries. Lebanon, for example, is an upper middle-income country. But close to 20 percent of its population—every fifth person—is a Syrian refugee.

Notes: UNHCR Population Statistics. CGD analysis. Headcounts only include ‘Asylum-seekers’, ‘Internally displaced persons’ and ‘Refugees (incl. refugee-like situations).’

Generally, when problems are long-term and concentrated in countries with cash-strapped public services, we tackle them using longer-term, subsidized lending (and policy advice for reforms that are attached to the cheap loans). World Bank lending is a primary example of this.

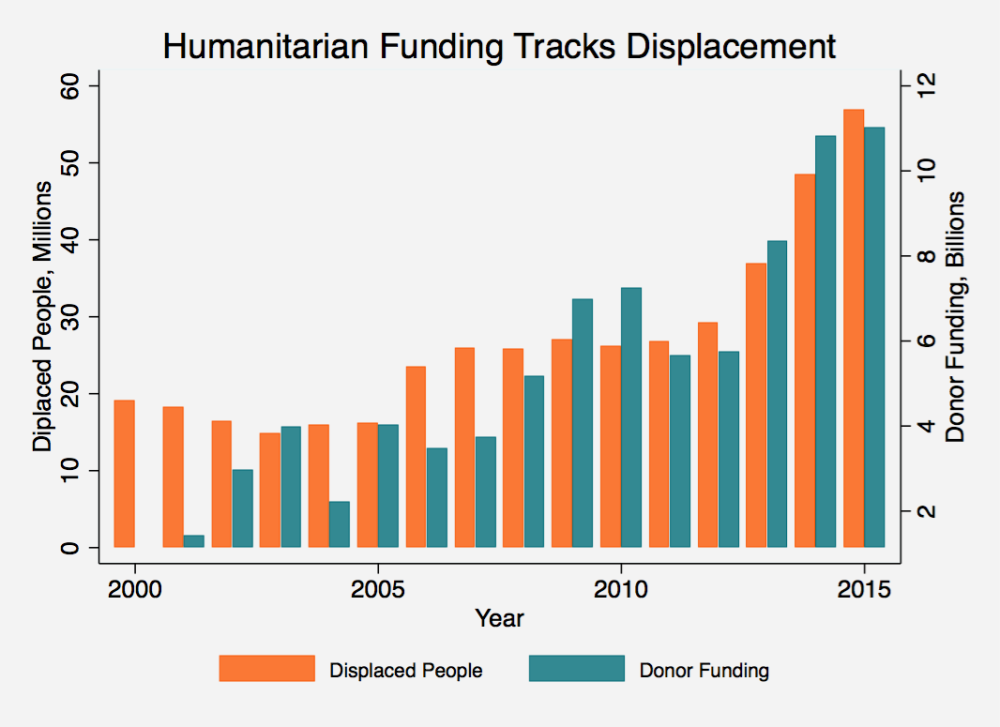

Displacement falls between the cracks of that model. Even though a significant portion of the caseload is long-term and requires different solutions, we are still largely using the same short-term humanitarian funds and approaches. The chart below shows the amount of funding donors have paid the humanitarian response plan process: the level of short-term humanitarian funding has grown in perfect lockstep with the number of displaced people.

Source: UNHCR Population Statistics and UNOCHA Financial Tracking System. CGD analysis. Headcounts only include ‘Asylum-seekers’, ‘Internally displaced persons’ and ‘Refugees (incl. refugee-like situations).’

That means we’re relying on the short-term financing of appeals, rather than the long-term development finance tools that might be a better match for protracted displacement. That’s a fundamental mismatch of financing tools and purpose—like trying to buy a house using a credit card instead of a mortgage.

Bridging the divide

Recent global summits have significantly increased awareness of the mismatch between the changed nature of displacement and legacy approaches. This includes innovations that bring together the expertise, resources and leverage of development and humanitarian actors.

For example, the World Bank’s Global Concessional Financing Facility now offers loans at cheaper rates to middle-income countries to address the needs of refugees and host communities. The broader Global Response Crisis Platform addresses prevention, preparedness, and response. And the Grand Bargain launched at the World Humanitarian Summit in Istanbul in May this year promises to increase humanitarian-development collaboration, in part through more joint analysis and planning.

There’s a lot of work left to do. We need to ensure that development solutions stay laser-focused on the well-being of both displaced people and the communities in which they live. And there are difficult questions about how to protect civilians while engaging governments. For example, IDPs are often beholden to the governments that displaced them.

Tackling these challenges means accepting that they’re tough, long-term, and mismatched to our legacy financing rules. Of course, getting the diagnosis right doesn't mean that the patient will get better. But it does mean that a combination of smart, brave political leadership and better-tailored financing can deliver the sustainable solutions that displaced people need—and deserve.

Thanks to Janeen Madan and Caitlin McKee at CGD and to Madeleine Gleave and Lauren Post at IRC for great comments and edits on an earlier draft. Naturally, all remaining errors are totally their fault.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.