Recommended

Key Recommendations

The White House should:

- Nominate a USAID administrator who will champion evidence-based policymaking.

USAID should:

- Establish a consolidated evidence and evaluation unit that reports directly to the administrator.

- Strengthen evaluation skills within missions by separating monitoring and evaluation functions.

- Use the procurement and program design processes to ensure interventions are based in evidence or integrate opportunities for experimentation and testing.

- Develop an impact evaluation strategy for each sector that prioritizes key questions.

- Invest in faster, less expensive data sources and impact evaluation methods.

- Advance efforts to analyze comparative cost-effectiveness.

US foreign assistance can and does deliver results.[1] There is documented evidence of aid programs saving lives and improving well-being across developing countries.[2] But in assessing whether federally funded international aid programs are achieving results and delivering value for money, the US government faces gaps in its understanding. Investments in evaluation can help provide answers that guide funding toward more effective programs and away from less effective approaches.

As the world’s largest bilateral donor responsible for managing around $20 billion in annual funding, the US Agency for International Development (USAID) has a particular responsibility to take an evidence-informed approach to its work. It also has a congressional mandate to do so. The Foundations for Evidence-Based Policy Act (“Evidence Act”), signed into law in early 2019, requires federal agencies to evaluate the impact of their programs; scale the use of data, evidence, and evaluation in the policymaking process; and increase public access to federally held data.[3] Across these standards, USAID already outperforms many federal agencies, suggesting a solid base upon which to build.[4]

About 10 years ago, USAID reinvigorated its commitment to evidence-based programming and policymaking and set out to build a culture of evaluation and learning. Key steps included establishing a new evaluation policy; creating the Bureau for Policy, Planning and Learning (PPL) and within it the Office of Learning, Evaluation and Research (LER); launching Development Innovation Ventures (DIV), a unit within the Global Development Lab which identifies and rigorously tests new solutions to development problems and helps scale those with strong evidence of impact and cost-effectiveness; and initiating a new research program to benchmark the cost effectiveness of USAID’s traditional programming against that of cash transfers. Still, there remains significant scope for improvement. USAID’s program decisions are not systematically informed by evidence, and while the agency produces more evaluations of its own work than it did a decade ago, relatively few are rigorous or high quality.

Over the last four years, however, momentum on evidence and evaluation has stalled at USAID. The Trump administration regularly demonstrated its skepticism of—even opposition to—development assistance by proposing huge budget cuts, attempting to rescind appropriated funds, and taking a transactional view of aid by frequently seeking to tie disbursements to foreign policy priorities.[5] In this environment, evidence and evaluation fell down the priority list.

Meanwhile, the need for evidence-based policymaking and programming has only grown. The COVID-19 pandemic has magnified hardship for many around the world, and the Biden administration will confront almost unprecedented development challenges.[6] Strengthening global health security and supporting global economic recovery will almost certainly be top priorities. But for these efforts to be as effective as possible, they must be underpinned by evidence. Furthermore, with the pandemic’s fiscal impact likely to squeeze future aid budgets, identifying and pursuing approaches that deliver value for money will be more important than ever.

USAID needs to recommit to advancing evidence-based policy and programming. Key objectives for the agency should include: increasing the proportion of USAID-funded programming that is grounded in evidence; investing in research on the effectiveness of interventions for which evidence is mixed or limited; and advancing efforts to understand more about the cost-effectiveness of the agency’s programs. This brief provides a set of targeted recommendations to pursue those goals.

The state of evidence-based decision-making at USAID: Progress and constraints

Types of evidence and their uses

USAID invests in and uses a range of different kinds of evidence. Understanding their differences is key for knowing what each can say about “results.”

“Monitoring and evaluation” (M&E)—and increasingly “monitoring, evaluation, and learning” (MEL)—refer to efforts to gather information about program results.

Performance monitoring is the ongoing collection of quantitative data (performance indicators) to gain insight into whether implementation is on track and whether basic objectives are being achieved. Performance indicators typically include outputs (e.g., farmers trained) and outcomes (e.g., hectares under improved cultivation).

Evaluation is, according to USAID’s evaluation policy, “the systematic collection and analysis of information about the characteristics and outcomes of strategies, projects, and activities as a basis for judgments to improve effectiveness, and timed to inform decisions about current and future programming.”[1] Evaluation has two main purposes: accountability and learning.

Performance evaluations seek to answer questions like what has the program achieved? How was it implemented? And how was it perceived? These evaluations often compare outcomes before and after the program but don’t include a counterfactual to attribute observable changes to the specific intervention. Done well, their findings can be valuable for program management and design.

Impact evaluations measure the change in outcomes that are directly attributable to a particular intervention. Impact evaluations use experimental methods (randomized control trials or RCTs) or quasi-experimental designs to construct a counterfactual that controls for other factors that might have affected outcomes in addition to the program.

USAID’s evaluation policy remains an industry gold standard. When introduced in early 2011, it gave new momentum to evaluation at USAID. In the years that followed, the number and quality of USAID evaluations increased.[7] Hundreds of USAID staff have been trained in evaluation concepts and processes, underscoring the idea that USAID staff are responsible for adding to the body of development evidence and learning from it.

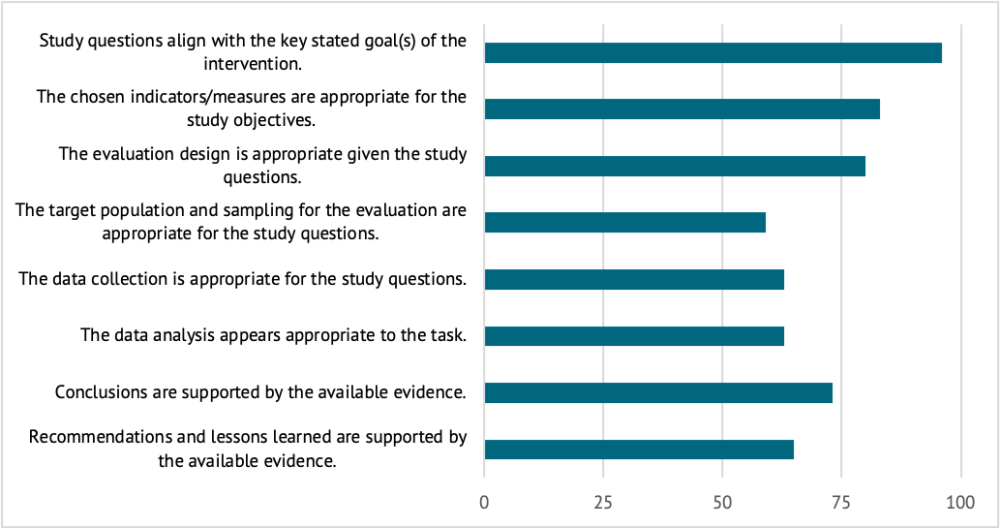

Despite these advances, there is considerable scope for improvement. First, evaluation quality remains mixed.[8] Average evaluation quality improved in the years after the evaluation policy was instituted, but improvement was uneven across studies and modest overall.[9] GAO studied a sample of USAID evaluations from FY2015 and found that only a quarter met all their quality criteria.[10] The most common deficiencies were in sampling, data collection and analysis, and ensuring that findings and recommendations were based on the data (figure 1). Quality problems affected both performance and impact evaluations but were more commonly found with performance evaluations.[11]

Figure 1. Percent of sampled USAID evaluations that met each of GAO’s evaluation quality criteria

Source: US Government Accountability Office, 2017. “Foreign Assistance: Agencies Can Improve the Quality and Dissemination of Program Evaluations.”

In addition, despite higher numbers of evaluations overall, impact evaluations—studies that can measure results attributable to a USAID program—remain rare.[12] While some parts of the agency—notably, parts of the Bureau for Economic Growth, Education, and Environment and the Democracy, Rights and Governance Center—have had periods of intentional investment in impact evaluations, they’ve been a low priority for much of the agency. Of course, impact evaluations aren’t always appropriate or feasible,[13] but they offer valuable learning opportunities for interventions where the evidence base is limited or mixed.

There are a number of constraints to producing more and higher quality evaluations at USAID. Time-strapped field staff are under pressure to execute programming, manage contracts, and fulfill reporting requirements. This can leave limited time to pursue evaluations and compress evaluation timelines, which can compromise their quality, especially the quality of sampling and data collection.[14]

Capacity constraints also play a role. Since 2011, USAID has hired more staff with evaluation expertise.[15] Nevertheless, many M&E staff, who spend most of their time on performance monitoring tasks, have limited evaluation experience or expertise. And when staff have limited time, incentive, or technical background, even strong evaluation training and guidance from PPL can only go so far. At USAID’s headquarters in Washington, both PPL and the pillar bureaus have in-house evaluation experts who can provide support to the field, but these resources are available by request, and opportunities to request support—both for identifying evaluation opportunities and planning for quality studies—can easily be overlooked.

Another challenge that plagues evaluation is one of timeliness. Evaluation, especially impact evaluation, is perceived as slow and expensive—and that is frequently a fair assessment. Program managers are reluctant to conduct evaluations if it will slow program implementation. And if evaluation results won’t be available until years after a program has concluded, program managers have little incentive to pursue them. Partly in response to questions of timeliness, there’s growing interest—including at USAID—in new, more rapid evaluation methodologies.[16] The agency is also exploring opportunities to use administrative data and other data sources (e.g., satellite or geospatial data) in places of slower, more costly, and sometimes duplicative specialized surveys.[17] But these remain somewhat rare.

While all these constraints apply to evaluations across the board, they are more acute for impact evaluations, which typically require more time and specialized knowledge.

Evidence informs policy and program decisions more episodically than systematically

The value of evaluation lies largely in its use. Indeed, basing funding decisions on analyses and evidence is a core principle of USAID’s Program Cycle.[18] But its implementation is inconsistent in practice. While the vast majority of USAID evaluations are used to inform some kind of decision making (usually just within the unit that commissioned the study), it’s not clear how well the broader universe of evidence—including evaluations conducted by other donors and organizations—is brought to bear.[19] In at least one documented case, an incomplete review of evidence led USAID to solicit bids for a program with a disproven theory of change.[20] As this example demonstrates, failure to examine the evidence case for an approach can lead to inefficient spending. It can also miss opportunities to pursue more effective approaches, or—where proposed approaches are untested (or undertested)—to plan an accompanying evaluation, as required by policy. USAID seeks to avoid this for large programs by requiring senior leadership to review proposals; as part of this process, staff are asked to include the evidence case for the selected approach.[22] But while this can be a helpful prompt, it’s unclear how heavily the evidence case is weighted relative to the other criteria under review, how the strength and comprehensiveness of the evidence presented is evaluated, or even what expectations for remediation—if warranted—would be at such a late stage in the design process.

There are several barriers to greater uptake of evidence in program design.[22] Again, time and capacity constraints loom large. Where evidence exists it’s often inaccessible to busy staff with little time to conduct a full evidence review and limited expertise in concepts relevant to understanding econometric research.[23] Summarizing and synthesizing evidence can help, and USAID and other organizations like 3ie have several tools and processes (e.g., evidence gap maps, synthesis reports, newsletters, knowledge sharing platforms, evidence summits) to help missions learn from evaluation findings, but these are not always widely used.[24]

Another barrier to evidence use is skepticism of its relevance. This is partially related to quality but not exclusively. Certainly, low-quality evaluations—those without a valid methodology or credible findings— won’t convey useful information. But questions of relevance can also surround high-quality studies. Because the results of an individual evaluation may not always be generalizable to other contexts, staff may (sometimes rightly) feel its findings are irrelevant to the project they are designing. Multiple evaluations of similar interventions in different contexts can strengthen the evidence base for a given approach, but the kind of replication and synthesis needed to achieve this type of meta-analysis has been rare. Evaluation resources are often spread broadly, and researchers tend to have professional incentives to pursue “cutting edge” questions.

It is also important to note that the primary objective of a significant portion of USAID funds is advancing US foreign policy interests—even if the investments are nominally about development. When development objectives are ancillary to the program’s core goals, staff may have less scope—or less time—to bring evidence to bear on program design.[25]

Costing and cost-effectiveness are understudied, though nascent efforts are encouraging

With aid budgets under pressure, USAID’s value for money will likely come under increased scrutiny. To be well positioned to defend development spending, USAID and foreign aid advocates would benefit from a robust understanding not only of program results (i.e., was the program better than nothing) but also answers to questions about opportunity cost: did a project work well enough to justify spending money on it compared to using those funds for something else? Is a project’s impact per dollar greater than that of an alternative?[26]

But while impact evaluations have been rare, impact evaluations that include the kind of cost analysis necessary to understand impact per dollar are rarer still.[27] And where cost analysis has been done, the underlying cost data has been of mixed quality and methodologies have often varied, limiting their comparability across studies.[28]

USAID has started to tackle the question of cost effectiveness. It funds and participates in the Costing Community of Practice, run out of the University of California, Berkeley’s Center for Effective Global Action, and the Office of Education established a cost measurement initiative to analyze program costs and link them to outcomes.[29] In addition, DIV has launched a series of costed impact evaluations that attempt to compare the per-dollar results of several “traditional” aid programs with those of cash transfers. The premise of this exercise, known as cash benchmarking, is that since cash transfers have a demonstrated ability to shift individual or household outcomes and are among the lowest cost interventions, they make a useful benchmark to determine whether a “traditional” program adds any value.[30] But while these efforts are promising, they are relatively new and niche and will require a champion for cost effectiveness to advance them.

Responsibilities for promoting evidence remain fragmented and reach to missions is limited

USAID made a number of bureaucratic changes to better implement its new focus on evidence. In 2010, the agency established the Bureau for Policy, Planning and Learning (PPL) and within that, the Office of Learning, Evaluation, and Research (LER) which sets operational policy and provides agency-wide guidance on monitoring, evaluation, and learning. The same year, USAID launched DIV, a unique program that identifies and rigorously tests new solutions to development problems and helps scale those that prove successful. In 2014, the agency created the Global Development Lab, which became the bureaucratic home for DIV, along with (among other units) the Center for Development Research (CDR), which supports the creation of scientific knowledge and evidence around USAID’s development priorities, and the Office of Evaluation and Impact Assessment (EIA), which supports evaluations of innovative approaches, especially related to science and technology.

These have been important structural advances to help refocus the agency on evidence and evaluation. But the configuration also has limitations. Responsibility for evidence and learning ends up fragmented across the agency, not only across the aforementioned units but also across pillar bureaus whose evaluation points of contact have a significant role in supporting evaluations and disseminating evidence. This may make it harder for mission staff to know where to turn for what type of support. And some functions, like capacity building around evidence and dissemination of evidence-based learning, may be duplicated. In addition, LER and DIV have had limited reach to missions where most evaluation efforts are managed. And because they are small units sitting within much larger bureaus, they—and their focus on evidence—can be overshadowed by their respective bureaus’ other activities.[31]

USAID’s impending restructuring provides an opportunity—and underscores the need to—ensure evidence and evaluation functions are elevated rather than sidelined in the shift. In response to a Trump administration call for agency reorganization, USAID put forward an agency-wide transformation plan, which includes several shifts in bureaucratic structure. Under the proposed reorganization, DIV will move into the new Bureau of Development, Democracy and Innovation, and LER and EIA will be combined into a new Office of Learning and Evaluation within a proposed new Bureau for Policy, Resources and Performance—though the latter still awaits congressional approval .[32] A core goal of the next phase of restructuring should be to elevate and consolidate the agency’s evidence, evaluation, and learning functions and extend their reach to better support missions.[33]

Policy recommendations

USAID has an opportunity to be a leader in evidence-based foreign aid. To elevate an evidence-oriented agenda at USAID and overcome barriers that undermine the generation of high-quality evidence and its systematic use, the next administration should prioritize the following actions. Some of these would involve the creation of new staff positions with corresponding resource implications. The next administration should make the case for increased hiring to fill these positions in an early budget request to Congress—highlighting their role in improving the effectiveness and efficiency of appropriated funds, as well as the decline in US direct hires over the past five years.[34]

The White House should:

- Nominate a USAID administrator who will champion evidence and commit to advancing evidence-based policymaking. High-level political support is critical for shifting agency practice and culture.[35] The nominee for USAID administrator should have a track record as an evidence champion who is clearly committed to advancing evidence-based policymaking at USAID. The nominees to head PPL (or the proposed new Bureau for Policy, Resources and Performance) and the pillar bureaus must be similarly committed to evidence, but administrator-level support will be critical for other senior leaders to be effective in their pursuit of evidence-based policymaking.

USAID should:

- Create a new, consolidated evidence and evaluation unit with leadership that reports directly to the administrator. Such a unit would consolidate and expand the evidence, evaluation, and learning functions—currently housed across PPL, the remnants of the Global Development Lab, and what’s now the Bureau of Development, Democracy and Innovation—under a new senior leadership position empowered, through its direct link to the administrator, to push forward an evidence-oriented agenda.[36] The unit’s structure would highlight and elevate evidence, evaluation, and learning functions rather than subsuming them under multiple larger bureaus. It would also reduce duplication and allow a more streamlined evidence and evaluation strategy. Two of the new or expanded functions of this unit should include:

- Stronger, centralized impact evaluation services: USAID should establish a team of impact evaluation support specialists who would proactively work with missions to identify opportunities to pursue impact evaluation, to ensure methods and sampling are adequate to the questions being asked, and to manage the implementation and dissemination of the evaluations. It is unrealistic for specialized impact evaluation skills to be diffused across missions, especially when this type of evaluation is often a small part of a typical mission M&E officer’s portfolio. Managed by the centralized evidence and evaluation unit, these staff could reside in Washington (with linkages to the pillar bureaus) and/or regional missions in order to serve multiple missions and be deployed, as needed, to embed within operational teams.[37] While this function could be partially covered by existing staff, it may require budget for additional staff salaries.

- “Evidence broker” functions: For communication about evidence to be relevant to policy and program decision makers, it must be tailored to their immediate needs.[38] Establishing a cadre of evidence broker staff—employing a hybrid set of analytical, policy, and communications skills—can, from a central or embedded position, socialize the results of new studies and translate relevant findings into targeted recommendations for program design.[39] Evidence brokers can also play a central role in the review and approval of the evidence case presented for new programs. This recommendation would entail creating new staff positions.

- Strengthen evaluation skills within missions. Even with centralized impact evaluation services, some mission-level evaluation functions will remain important to identifying opportunities for impact evaluation, to work with a centralized impact evaluation support team, and to ensure high quality performance evaluations. Given the amount of time M&E staff spend on performance monitoring and fulfilling reporting requirements, USAID should separate monitoring and evaluation functions into two staff roles at the mission level.[40] In selecting evaluation staff, they should weigh heavily a familiarity and experience with quantitative and qualitative evaluation methods. This recommendation would entail creating new field staff positions.

- Build evidence use and generation into the procurement and program design processes. USAID should frame its award solicitations around evidence generation and use.[41] This would come with no additional budget requirements.

- Where the evidence base is weak or contradictory, USAID is less able to provide strict technical guidance about implementation and the agency should pursue more flexible award types that allow for experimentation and testing and should evaluate bids, in part, on how well the proposal would accommodate evaluation. Awards for untested approaches should start small with opportunities to expand depending on evidence of effect.

- Where there is a stronger evidence base, either a (more prescriptive) contract or (more flexible) cooperative agreement may be used, but solicitations for either type of award should adequately reflect the state of evidence. In a solicitation for a contract, USAID should summarize the body of evidence upon which its proposal is built. For cooperative agreements, the solicitation should require bidders to summarize the relevant evidence that motivates their proposed approach and bids should be scored, drawing on the expertise of evidence brokers or other M&E staff, on how well the proposed approach demonstrates an understanding of the existing evidence.

- For co-creation processes, evidence brokers or other M&E staff should be involved in early convenings to lay out the evidence base, discuss theories of change, and outline expectations for building evidence.

- Focus impact evaluation resources more strategically. To improve the utility and relevance of its evaluations, LER (or its successor), in partnership with the pillar bureaus, should create a strategy for each sector that serves to focus impact evaluation resources on a limited set of key questions.[42] Narrower than a typical learning agenda—which, in the name of consensus, tends to encompass too many questions without meaningful prioritization[43]—the strategy should emphasize questions about common or highly funded USAID approaches and include space for replication rather than exclusively focusing on “cutting edge” research. While strategy development itself carries no budget implications, implementing it will require bureaus and missions to set aside program funds on the order of three to five percent to finance evaluations.

- Invest in faster, less expensive impact evaluation methods. To reduce barriers to pursuing impact evaluation, PPL (or its successor) should encourage and incentivize methods that lower the cost of impact evaluation and yield more timely results. These should include prioritizing the use of administrative data where possible, accompanied, as relevant, by support to improve administrative data quality; expanding efforts to use other non-survey data sources, like satellite or geospatial data; and experimenting with new rapid evaluation methodologies.

- Advance cost-effectiveness analysis, both internally and industry wide. USAID should redouble its efforts to understand comparative cost-effectiveness. USAID’s next steps—which can be accomplished at minimal additional cost—should include expanding its support for and leadership in multi-stakeholder efforts to establish a common costing methodology to enable more consistent and available cost evidence.[44] Since each organization benefits from the generation of evidence by others, a coordinated effort is critical. The agency should then adopt a commonly accepted costing methodology and ensure impact evaluations begin to include cost data.[45] USAID should also expand its cash benchmarking work by prioritizing questions for costed impact evaluation and synthesizing findings on the range of per-dollar results of different interventions.[46] This effort should also include external coordination. As a pioneering donor in cash benchmarking, USAID should seek to convene other donors interested in costed impact evaluation and/or cash benchmarking to join forces to identify gaps and address them in a strategic and intentional way.

Additional reading

Sarah Rose and Amanda Glassman, 2017. “Advancing the Evidence Agenda at USAID.” CGD Note. Center for Global Development.

Sarah Rose, 2018. “As USAID Thinks about Procurement and Program Design, It Should Keep Evidence in Mind.” CGD Blog. Center for Global Development.

Sarah Rose and Amanda Glassman, 2018. “Committing to Cost-Effectiveness: USAID's New Effort to Benchmark for Greater Impact.” CGD Note. Center for Global Development.

Center for Global Development Evaluation Gap Working Group, 2006. When Will We Ever Learn: Improving Lives through Impact Evaluation. Center for Global Development.

The Lugar Center and The Modernizing Foreign Assistance Network, 2017. From Evidence to Learning: Recommendations to Improve U.S. Foreign Assistance Evaluation.

Thanks to Annette Brown, Anne Healy, Rebecca Wolfe, and many others for useful conversations that helped inform the work.

[1] Sarah Rose, 2017. Some Answers to the Perpetual Question: Does US Foreign Aid Work—and How Should the US Government Move Forward with What We Know? CGD Blog. Center for Global Development.

[2] Amanda Glassman and Miriam Temin, 2016. Millions Saved: New Cases of Proven Success in Global Health. Center for Global Development; Eran Bendavid, Charles Holmes, Jay Bhattacharya, and Grant Miller. 2012. “HIV Development Assistance and Adult Mortality in Africa.” JAMA. 2012;307(19):2060–2067; Michael Clemens, Steven Radelet, Rikhil R. Bhavnani, and Samuel Bazzi, 2011. Counting Chickens When They Hatch: Timing and the Effects of Aid on Growth. CGD Working Paper 44. Center for Global Development; Jonathan Glennie and Andy Sumner, 2014. The $138.5 Billion Question: When Does Foreign Aid Work (and When Doesn’t It)? CGD Policy Paper 049. Center for Global Development.

[3] Foundations for Evidence-Based Policymaking Act of 2018. 2019. Pub. L. No. 115–435. https://www.congress.gov/115/plaws/publ435/PLAW-115publ435.pdf.

[4] Results for America, 2019. “Results for America Recognizes Leading Federal Agencies for Using Evidence and Data to Improve Lives.” Press Release, October 29, 2019. Results for America

[5] Erin Collinson and Jocilyn Estes, 2020. Cutting Aid is Still A Big Deal: Why We Should Pay Attention to the FY21 Budget Request. CGD Blog. Center for Global Development, Michael Igoe, 2019. Trump Administration Resurrects 'Rescission' Proposal in Latest Attack on US Aid Spending. August 7, 2019. Devex; Michael Igoe, 2020. Disrupt and compete: How Trump changed US foreign aid. August 21, 2020. Devex.

[6] Christoph Lanker, Nishant Yonzan, Daniel Gerszon Mahler, R. Andres Castaneda Aguilar, Haoyu Wu, and Melina Feury, 2020. Updated Estimates of the Impact of COVID-19 on Global Poverty: The Effect of New Data. October 7, 2020. World Bank Blog.

[7] Molly Hageboeck, Micah Frumkin, and Stephanie Monschein, 2013. Meta-Evaluation of Quality and Coverage of USAID Evaluations 2009-2012. Management Systems International.

[8] Julia Goldberg Raifman, Felix Lam, Janeen Madan Keller, Alexander Radunsky, and William Savedoff, 2017. Evaluating Evaluations: Assessing the Quality of Aid Agency Evaluations in Global Health. CGD Working Paper 461. Center for Global Development.

[9] Hageboeck et al., 2013. See page 156 for more details on how MSI constructed its composite quality score

[10] US Government Accountability Office, 2017. “Foreign Assistance: Agencies Can Improve the Quality and Dissemination of Program Evaluations.” US Government Accountability Office, March 2017.

[11] US Government Accountability Office, 2017; Goldberg Raifman, et al., 2017.

[12] Hageboeck, et al.; US Government Accountability Office, 2017; Goldberg Raifman, et al., 2017.

[13] Mary Kay Gugerty and Dean Karlan, 2018. “Ten Reasons Not to Measure Impact—and What to Do Instead.” Stanford Social Innovation Review.

[14] The Lugar Center and the Modernizing Foreign Assistance Network, 2017. From Evidence to Learning: Recommendations to Improve U.S. Foreign Assistance Evaluation.

[15] The Lugar Center and the Modernizing Foreign Assistance Network, 2017.

[16] International Initiative for Impact Evaluation, 2020. “Big Data Systematic Map.” https://gapmaps.3ieimpact.org/node/24092/about; USAID. n.d. “Rapid Feedback Monitoring, Evaluation, Research and Learning (Rapid Feedback MERL).”

[17] For example, the College of William and Mary’s AidData, with funding from USAID, has conducted innovative RCTs using geospatial data (https://www.aiddata.org/gie), including of USAID programs (Ariel BenYishay, Rachel Trichler, Dan Runfola, and Seth Goodman, 2018. A Quiet Revolution in Impact Evaluation at USAID. Future Development Blog. Brookings Institution). And USAID’s own GeoCenter is a strong resource that can help missions apply geospatial data for monitoring and evaluation purposes (https://www.usaid.gov/digital-development/advanced-geographic-and-data-analysis). See also the brief in this series on US global health leadership, which recommends US support to partner countries to strengthen the accuracy of routinely reported administrative data to help enable more real-time analytics to inform health policy and programming.

[18] USAID, 2020. ADS Chapter 201: Program Cycle Operational Policy. https://www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/documents/1870/201.pdf.

[19] Molly Hageboeck, Micah Frumkin, Jenna L. Heavenrich, Lala Kasimova, Melvin Mark, and Aníbal Pérez-Liñán, 2016. “Evaluation Utilization at USAID.” Management Systems International; USAID, 2020. “Evaluation.” https://www.usaid.gov/evaluation.

[20] USAID/Ukraine issued a solicitation for bids to implement a community driven development program with the goal of creating greater acceptance of shared culture and increasing participation to improve governance and resolve community problems. However, a synthesis done by the International Initiative for Impact Evaluation (3ie) of 25 impact evaluations of community driven development programs found that they have little or no impact on social cohesion and governance outcomes (Sarah Rose, 2018. As USAID Thinks about Procurement and Program Design, It Should Keep Evidence in Mind. CGD Blog. Center for Global Development.

[21]This refers to the Senior Obligation Alignment Review (SOAR).

[22] Sarah Rose and Amanda Glassman, 2017. Advancing the Evidence Agenda at USAID. CGD Note. Center for Global Development.

[23] Even USAID’s own online evaluation repository is a challenge to navigate (The Lugar Center and the Modernizing Foreign Assistance Network, 2017).

[24] International Initiative for Impact Evaluation. Evidence Gap Maps. https://www.3ieimpact.org/evidence-hub/evidence-gap-maps; Hageboeck, et al., 2016.

[25] Rose, 2017.

[26] Iqbal Dhaliwal, Esther Duflo, Rachel Glennerster, and Caitlin Tulloch, 2013. "Comparative Cost-Effectiveness Analysis to Inform Policy in Developing Countries: A General Framework with Applications for Education." In Education Policy in Developing Countries. Ed. Paul Glewwe. University of Chicago Press; Elizabeth Brown and Jeffrey Tanner, 2019. Integrating Value for Money and Impact Evaluations: Issues, Institutions, and Opportunities. Policy Research Working Paper 9041. World Bank.

[27] David Evans, 2016. Why don’t economists do cost analysis in their impact evaluations? World Bank Blog. World Bank.

[28] University of California, Berkeley Center for Effective Global Action. https://cega.berkeley.edu/costing-community-of-practice-ccop/.

[29] USAID, 2020. “USAID Cost Measurement.” https://www.edu-links.org/resources/usaid-cost-measurement.

[30] Craig McIntosh and Andrew Zeitlin, 2018. Benchmarking a Child Nutrition Program against Cash: Experimental Evidence from Rwanda. Innovations for Poverty Action; Craig McIntosh and Andrew Zeitlin, 2020. Using Household Grants to Benchmark the Cost Effectiveness of a USAID Workforce Readiness Program. Innovations for Poverty Action; Sarah Rose and Amanda Glassman, 2018. Committing to Cost-Effectiveness: USAID's New Effort to Benchmark for Greater Impact. CGD Note. Center for Global Development; Sarah Rose, 2020. The Case for Cash—Beyond COVID—Gains Strength: New Data on Comparative Cost-Effectiveness. CGD Blog. Center for Global Development.

[31] Rose and Glassman, 2017.

[22] USAID Congressional Notifications on the bureaucratic restructuring https://pages.devex.com/rs/685-KBL-765/images/USAID-Congressional-Notifications.pdf.

[33] For example, DIV will be one part of one of nine sub-units that make up the Bureau of Development, Democracy and Innovation.

[34] In FY2019, USAID had 3,551 direct hires, compared with 3,804 in FY2015 (USAID. 2019. “Agency Financial Report Fiscal Year 2019.” https://www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/documents/1868/USAIDFY2019AFR_508R.pdf; USAID. 2016. “USAID Staffing Report to Congress.” https://www.usaid.gov/open/staffing/fy16

[35] Many have pointed out that the key to the success of USAID’s evaluation policy and the creation of PPL and DIV was Administrator Shah’s prioritization of evidence-based policymaking.

[36] The unit’s leadership could fulfill an empowered and expanded version of the chief evaluation officer required in the Evidence Act.

[26] The US General Services Administration’s Office of Evaluation Sciences and the World Bank’s Gender Innovation Lab provide two successful models of this approach.

[38] The Millennium Challenge Corporation, which was founded with evidence-based decision-making at the core of its model, recently created an evidence broker position. It has found that operations staff are engaging with evidence more than in the past thanks to direct conversations with staff whose job it is to make evidence relevant to their work, along with synthesis products that make evaluation findings more accessible and legible (Sarah Rose, 2019. MCC Turns Research into Learning. CGD Blog. Center for Global Development.

[39] A similar recommendation was put forth in the Lugar Center and the Modernizing Foreign Assistance Network (2017).

[40] This could align with the Evidence Act’s provision for a new evaluation specialist job track.

[41] Rose, 2018.

[42] An impact evaluation strategy would contribute, in part, to USAID’s response to the Evidence Act’s requirement to develop an “agency evidence-building plan.” The plan needs to include, among other things, a list of questions for which the agency intends to build the evidence base, a list of data the agency will collect, and the methods the agency will use to develop this evidence.

[43] The Self-Reliance Learning Agenda, for example, contains 13 main questions—but over 50 sub-questions—few of which are rigorously testable.

[44] This could include, for instance, expanding its work with the University of Berkeley’s Center for Effective Global Action’s Costing Community of Practice.

[45] For example, the International Rescue Committee’s Airbel Impact Lab, in partnership with Mercy Corps, Save the Children, Action Against Hunger Spain, and CARE USA, has developed a Systematic Cost Analysis (SCAN) tool to help simplify and systematize cost analysis (https://airbel.rescue.org/projects/scan/).

[46] Rose, 2020.

Rights & Permissions

You may use and disseminate CGD’s publications under these conditions.