Recommended

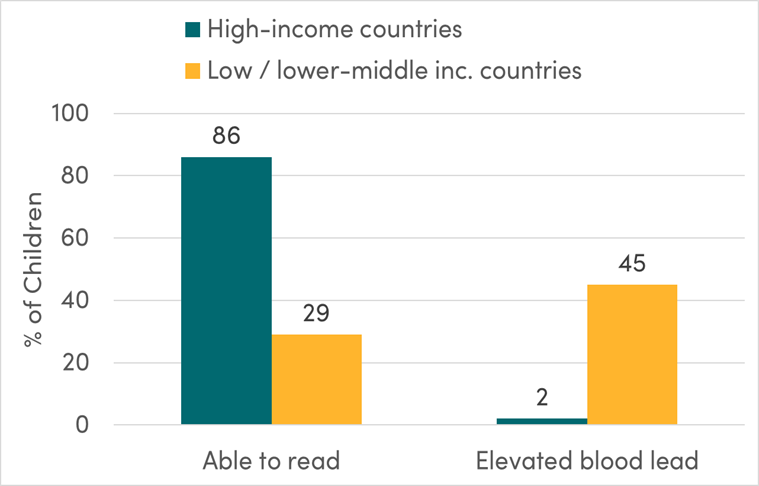

Readers of this blog have heard us talk for years about the “global learning crisis.” In 2021, the World Bank and the UNESCO Institute for Statistics estimated that fewer than half of 10-year-olds in low-income countries can read and comprehend a simple text. Foreign aid donors often attribute these low scores to poor quality teaching, and prescribe remedies focused on improving pedagogy and teacher accountability. But what if something else altogether, outside of the control of teachers and schools, is preventing children in poor countries from learning?

In a new paper, we examine the connection between exposure to lead—a dangerous but prevalent neurotoxicant—and children’s learning outcomes. We find that lead poisoning alone could account for more than 20 percent of the learning gap between rich and poor countries. Given the comparative ease of, say, banning lead paint compared to comprehensive education reform, policymakers interested in improving children’s learning outcomes may want to consider lead exposure as fairly low-hanging fruit.

Hundreds of millions of children are still poisoned by lead

In the United States, the share of children with elevated blood lead levels (>5 mcg/dL) fell from roughly 100 percent around 1980 to small single-digit percentages today, thanks in part to the phase out of leaded gasoline. Most of the rich world has similarly low levels of lead exposure.

Figure 1. Reading proficiency is low in developing countries, and lead exposure is high

Note: The share of children able to read is the World Bank estimate for minimum reading proficiency at the end of primary school. The share of children lead poisoned is calculated from the numerator in the IHME/UNICEF “Toxic Truth” report and the denominator in UN population estimates.

Progress hasn’t been universal though. While developing countries also phased out leaded gasoline, they didn’t reap the same benefits. Exposure from a variety of sources—like leaded paint, cookware, cosmetics, adulterated spices, and leakage from backyard battery recycling—means half of children in low- and lower-middle income countries still have elevated blood lead levels.

The effect of lead on learning outcomes

Almost all estimates of the effect of lead poisoning on cognition are observational rather than experimental. Since correlation is not causation, genuine questions remain about the causal link here.

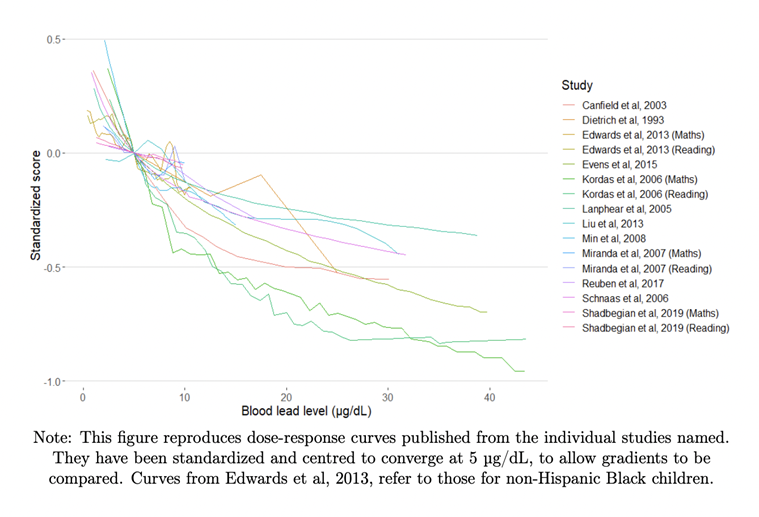

In a new CGD paper, we present a systematic review of 47 papers estimating the relationship between lead exposure and learning outcomes. While most of this literature has focused on IQ as the outcome, we included 15 studies measuring reading and/or mathematics test scores as well. A few points bear emphasis:

First, we take some reassurance that effects are causal due to the consistency of the effects across dozens of studies, author teams, and countries. Lead is pretty robustly correlated with low learning. There’s also a pretty consistent pattern in the shape of this relationship, with bigger effects on cognition from the first several micrograms of lead in a child’s blood, as shown in the lines below which start off steep and eventually flatten out.

Figure 2: The dose-response curve between individual blood and test scores

Second, the tendency for low-income, low-education households to have higher lead levels is real, but doesn’t seem to explain the whole effect. It is true that studies which control for things like parental income and IQ produce a smaller relationship between lead and learning outcomes. And there’s some evidence of publication bias: when looking at the distribution of statistical results there are anomalies suggesting insignificant results don’t get published, or get nudged over the line into significance.

But adjusting for these biases doesn’t appear to kill the result. And our confidence is reinforced by the handful of studies exploiting natural experiments – like the banning of leaded gasoline – to get closer to causality. These too tend to produce fairly robust negative impacts of lead on learning.

In our meta-analysis, we focus on estimates which include parental controls, and we adjust for the potential effect of publication bias as best we can. The end result is an effect that remains pretty big in educational terms: a doubling of blood lead levels (more precisely: 1 natural log point increase) implies a 0.12 standard deviation reduction in learning outcomes.

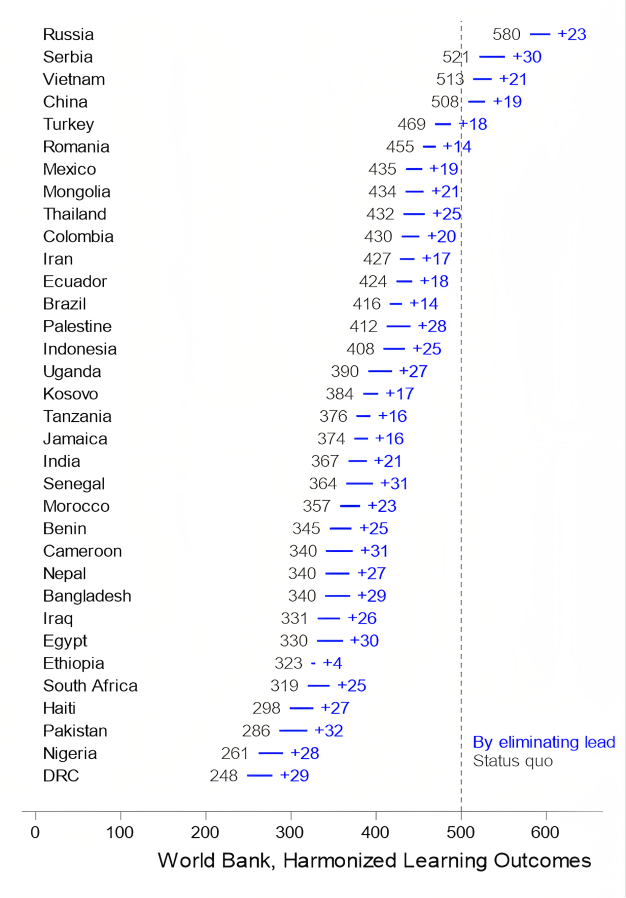

Policy simulation 1: Eliminating lead in developing countries

The good news is that lead exposure is a problem which can be solved. It should be possible to eliminate lead poisoning among children—most high-income countries have almost already done so. But to do this, we need to get serious about addressing the problem, and the first step is to better understand the impact lead poisoning has. Our paper includes two policy simulations to do just that.

We simulated the effect on test scores if blood lead levels in developing countries were reduced to the levels found in the United States. We used the World Bank’s harmonised learning outcomes scale, where the mean in rich countries is around 500 points with most developing countries scoring well below this (figure 3). Reducing blood lead levels would have a significant improvement in scores for the countries in our sample: ranging from four to 31 points on the scale. As an example, the lowest scoring country, the Democratic Republic of Congo, lies 250 points below the mean of 500, and reducing blood lead levels would improve scores by 29 points. These findings suggest that lead exposure plays a significant role in explaining learning gaps between rich and poor countries.

Figure 3. The effect of eliminating blood lead levels on national learning outcomes

Note: This figure shows the simulated effect on Harmonized Learning Outcomes for each country of reducing average blood lead levels to US levels (0.5 mcg/dl).

Policy simulation 2: The impact of new regulations and remediation

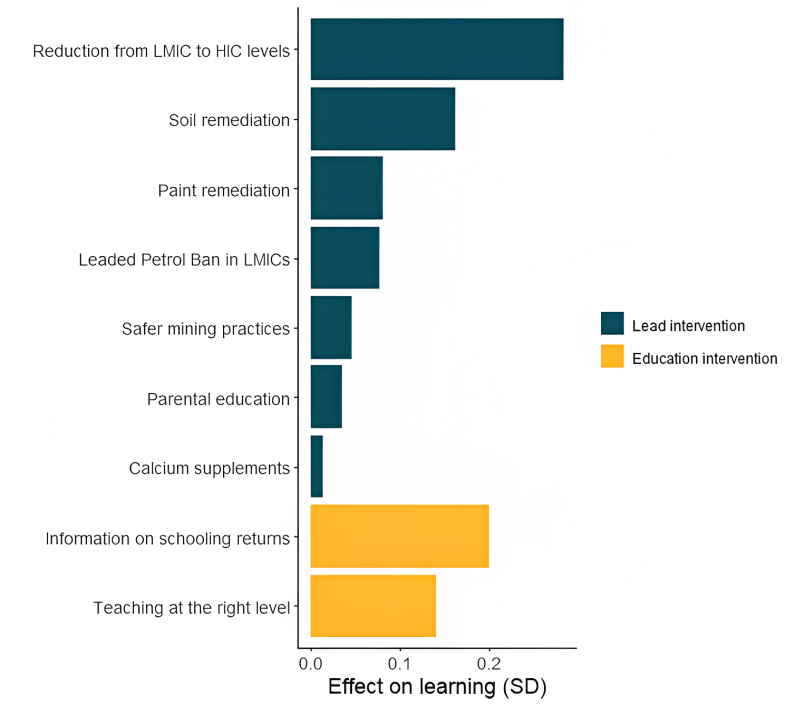

In reality, it’s impossible to eliminate lead poisoning instantaneously, though it is possible to make rapid progress. The most important intervention has already been implemented: banning leaded petrol, which shows that large reductions in blood lead levels are possible in rich and poor countries. We considered which other interventions might successfully reduce childhood lead poisoning and what their impact would be on learning outcomes.

It’s useful to distinguish several categories of policy response: regulatory, educational, medical, and targeted environmental interventions. Targeted environmental interventions, such as soil remediation in highly polluted areas, have shown large reductions in blood lead levels. However, such interventions are costly and we have limited evidence from developing countries. Educational interventions, such as providing information and advice to parents on reducing lead exposure, have led to reasonable reductions in blood lead levels in some countries. Medical interventions, particularly calcium supplementation, have also shown promising results in some contexts.

In short, some of the policy responses with modest effect sizes here—like parental education or calcium supplements—are cheap and potentially applicable to millions of kids at once.

Figure 4. The effect of feasible interventions on learning outcomes

Note: Where we have more than one study for an intervention category, this figure shows the median of effect sizes for those studies.

Eradicating lead poisoning: a neglected education priority

The potential learning gains from the elimination of childhood poisoning are comparable to many popular education reform priorities in the developing world. For instance, experimental evidence on “teaching at the right level” in India (a highly celebrated pedagogical approach pioneered by the NGO Pratham) found learning gains of 0.28 standard deviations. And USAID’s early-grade reading program in Kenya – among the most successful in its entire global portfolio – led to learning gains of 0.4 standard deviations in reading fluency. It doesn’t need to be a question of either/or to improve pedagogy or eradicate lead, but it is notable that the benefits of reducing lead exposure may be on par with the most celebrated educational interventions.

In cost-benefit terms, a focus on lead exposure may be justified solely on education grounds—even ignoring the potentially huge impacts of lead on things like cardiovascular disease— if countries are able to achieve significant reductions in lead exposure through low-cost, large-scale policy reforms such as improved regulation of the lead paint and lead battery industries.

Sometimes, pointing out the obvious fact that things outside the classroom undermine children’s educational outcomes in poor countries sounds a bit like saying, “let’s end global poverty, cure all disease, and achieve world peace, then we can worry about low learning levels.” We think the case for eradicating lead is different. It’s been done. It’s fairly cheap. And a handful of simple policies could go part way to closing the learning gaps between rich and poor countries.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.

Image credit for social media/web: Joanne Dale/ Adobe Stock