-

What if you realized your true potential? One intervention to improve students’ performance is to show them that with hard work, they can “grow” their intelligence, just like athletes can grow their muscles. Ganimian tested this in 200+ public high schools in Argentina. The result? No impact: no impact on student effort, no impact on student test scores, no impact on dropout rates, no impact on repetition rates, and no impact on plans to continue studying after high school. (With so many negatives, the paper begins to sound like a familiar children’s book.) Another evaluation tried this in 800 secondary schools in Peru: they did find an effect in math achievement in at least some schools. A third evaluated it in 65 secondary schools in the US and demonstrated an improvement in grades, principally for low-performers. (It also led high-performers to take more challenging classes.) Ganimian’s study also gives a comprehensive rundown of the 25 total previous studies to examine growth mindset across six countries. (También hay un resumen del estudio en la Argentina en español.)

-

When do countries with more effective education systems pull away from the pack? Singh compares children’s learning over time in Ethiopia, India, Peru, and Vietnam in a newly published paper. The big gaps in achievement open up in the first two to three years of school. Vietnam leaps ahead by the time kids are age 8, and the cross-country rankings then remain constant through age 15. If you want a successful education system, get those initial years right. (For the author’s quick take, check out his Twitter thread. Here’s an open-access version of the final paper.)

-

Is education the key to women’s health? Maybe a small key on a door with lots of locks. In two recently published reviews, researchers examine the links in low- and middle-income countries. Psaki and others examine the impact of education on sexual and reproductive health. Across 35 studies, they find do find effects, most consistently on women having fewer children and remaining HIV negative. But the effects tends to be small in size. A small, positive effect is still an effect, and education hopefully achieves other goals, but education is not the principal solution for sexual health outcomes. In another review, Mensch and others question one of the most popular pieces of conventional wisdom in international development: the link between women’s education and the health of their children. Lots of studies find a correlation, but few correct for the fact that women who get an education are often different from women who don’t for other reasons. For example, women who get an education often had more income to start with, which could obviously affect their children’s health. Studies that seek to examine the causal link find much more mixed results: Only 18 out of 46 estimates show a positive, statistically, significant impact. There’s something there, but it’s not as big or as consistent as most people have claimed.

-

Financial literacy, now in tablet form. The evidence on financial literacy isn’t promising, as Tim Ogden recounted a couple of months ago. A new study by Attanasio and others proposes that classroom-style settings are part of the problem, particularly for low-income recipients. A tablet-based financial education program in Colombia helped female recipients of a cash transfer program expand their financial knowledge, improve attitudes toward financial services, and it even increased their savings. Two years later, the savings results remain, but not so much the impact on knowledge. The effects were largest for poorer and less educated users.

-

A primer in global girls’ education in seven stunning charts. Jakiela and Hares lay out five key facts about girls’ education with seven charts. They find that (1) women are more educated today than ever before in history, (2) gender gaps almost never persist in highly educated countries, (3) in many countries, gender gaps worsen before they improve, (4) the way most people measure gender gaps in test scores is wrong, and (5) closing gender gaps in education won’t get you gender equality. (We should still close gender gaps in education!)

In case you missed it, last week I wrote about 10 school-related interventions where just providing information led to improved educational or health outcomes.

This week, on Wednesday and Thursday, is the Research on Improving Systems of Education—RISE—conference. You can check out the program and then watch the entire conference online.

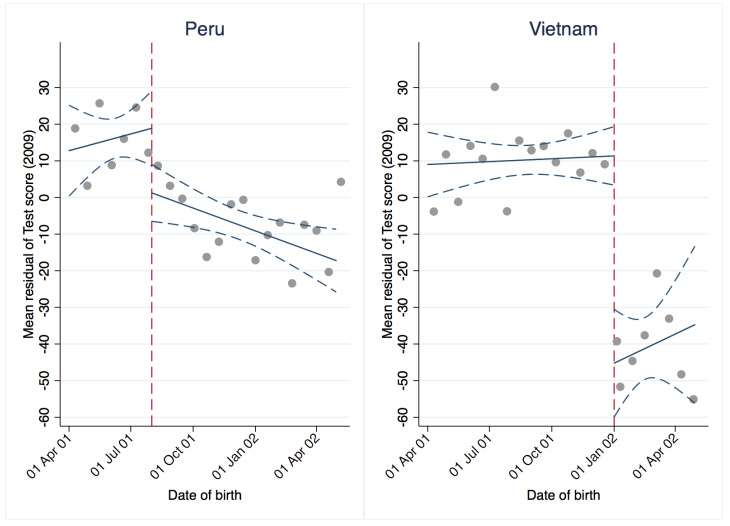

Chart of the week: What’s the impact of one more year of schooling on learning? In Vietnam, it’s pretty high!

Students to the left of the dotted line have one more year of schooling because they were born after the deadline. This is from Singh 2019.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.