Recommended

As sub-Saharan Africa grapples with the COVID-19 pandemic and its economic fallout, policymakers in Nigeria—Africa’s largest economy and home to about half of West Africa’s population—are increasingly recognizing a need for localised solutions driven by relevant evidence and local actors. But poor data infrastructures and significant undertesting severely hamper their efforts to attain this goal. The international community can play a key—and urgent—role in helping address these problems. As Nigeria begins to relax stay-at-home orders, Nigerian policymakers, with support from its development partners, should adjust restrictions in line with local circumstances and re-focus on the essential building blocks of health system strengthening.

A snapshot of the economic and health system context

About half of Nigeria’s 202 million people live in extreme poverty, and only three in ten have safe drinking water and sanitation. Seven in ten urban residents live in slum conditions, and more than 90 percent of the workforce are in the informal sector. Nigeria has the world’s largest malaria burden, and any progress in alleviating that burden is now under threat by the disruption to services caused by COVID-19.

Even before COVID-19, Nigeria’s economy was severely impacted by the recent collapse in international oil prices and demand for oil products. It is Africa’s biggest oil exporter, with the continent’s largest reserves of gas. However, oil and gas exports, 84 percent of all Nigerian exports, are expected to fall by US$26.5 billion as a result of the pandemic, with ensuing reductions in government revenues. The IMF approved US$3.4 billion in emergency financial assistance in response to the fiscal shock.

The Nigerian government has committed to achieving universal health coverage (UHC) by strengthening primary health care services through the creation of a US$114.7 million Basic Healthcare Provision Fund. Unfortunately, progress has been slow and services rely on many patients paying out-of-pocket fees. Notably, 5 percent of the fund was allocated for national health emergencies and responses to epidemics. The new “Primary Care Under One Roof” policy was paving the way for UHC. The authorities are now working with the private sector to establish a COVID-19 crisis intervention fund (N500 billion, US$1.3 billion) to upgrade healthcare facilities and administration.

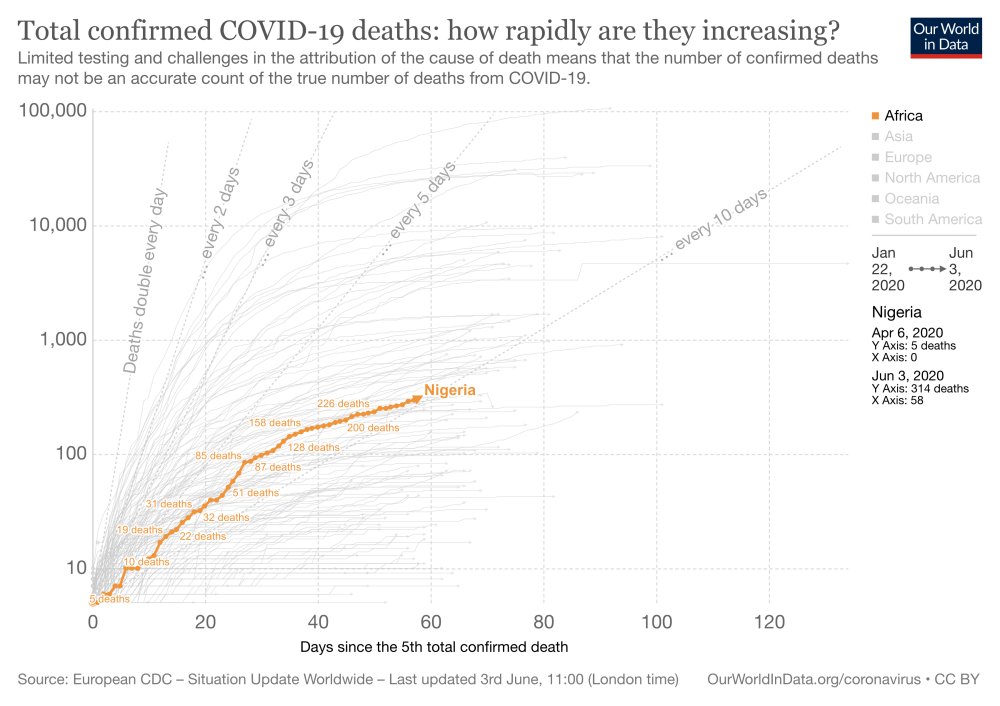

Figure 1. Total confirmed COVID-19 deaths in Nigeria: how rapidly are they increasing?

The spread of COVID-19 in Nigeria: low burden or low levels of testing?

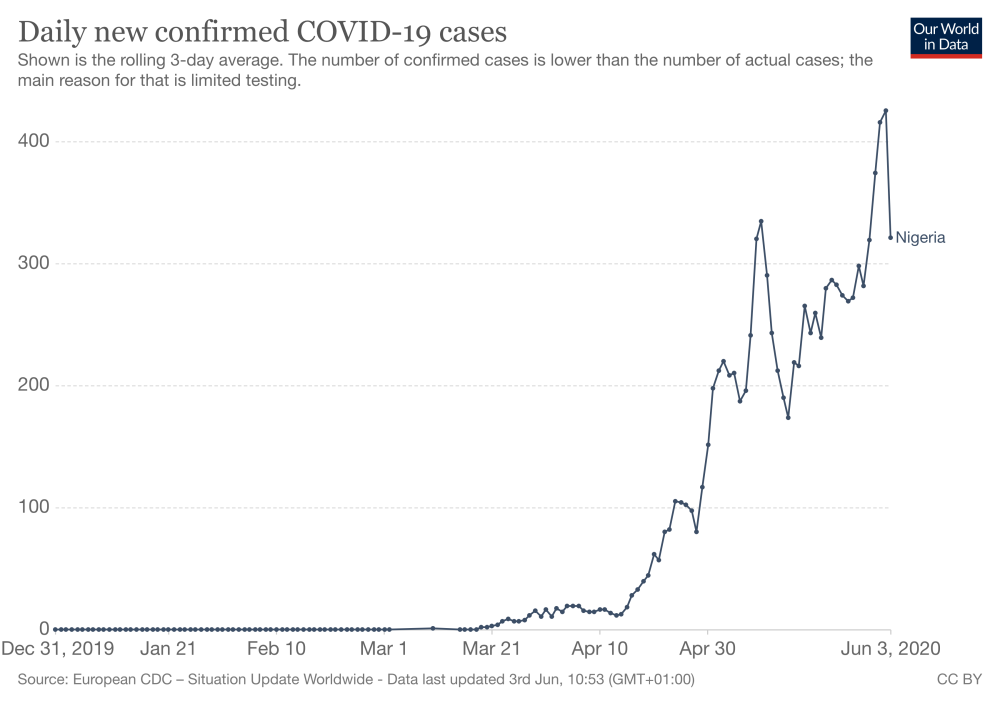

The epicentres of Nigeria’s COVID-19 infection are Lagos, Kano, and Abuja. As of 3 June, the Nigerian CDC reported 10,819 positive cases and 314 deaths. (See also Charts 1 and 2.) But there is no coordinated community testing to estimate prevalence, so the seemingly low rates for such a large country may in fact reflect very low levels of testing, and that only symptomatic testing is being conducted. (This is by no means a Nigeria-only problem: only about 0.1 percent of Africa’s population has been tested for COVID-19.)

Most identified COVID-19 cases in Nigeria have been in active people between 31 and 40 years old, with most presumably related to travel outside and within Nigeria. Initially senior government officials were the most affected, but infection has now become widespread through community transmission. Unmitigated, projections suggest the total number of symptomatic cases will be between 60 and 76 million within a year.

Nigeria’s public health response to COVID-19: national lockdowns and collateral harm

Nigerian president Muhammadu Buhari formed a presidential task force on COVID-19 and has adopted an official strategy to test, treat, trace, and isolate. But testing and tracing aren’t working as they should. There are too few test kits, and contact tracing has been limited because there are not enough workers to do it. This is an unfortunate contrast, since stringent contract tracing with the speedy isolation of potentially infectious contacts has been credited as key to Nigeria’s successful Ebola response.

State governments, influenced by similar moves by other governments, imposed stay at home orders so that only those providing essential services and transporting food items were allowed to move around. Unsurprisingly, some individuals defied the restrictions, especially those who lead a hand-to-mouth existence, for whom lockdowns mean a real risk of starvation. Beyond this, people living in low-density areas are better able to maintain physical distancing than those who live in poorer areas and in urban slums.

Kano, Nigeria’s second largest city, has been severely affected by COVID-19. The reported spike in deaths could reflect both the direct effects of infection and indirect effects from the “crowding out” of other health services, including those provided in private facilities. Unfortunately, however, there is little information to fully understand the situation on the ground, since there are no records on the socioeconomic status of cases and deaths.

On 1 May, about five weeks into lockdown, President Buhari set a goal for easing the restrictions, noting that the measures have imposed “a very heavy economic cost.” Several restrictions remain and the easing will be phased; still, some fear that any easing is premature given concerns about new cases, testing levels, and insufficient resources to handle a significant increase in symptomatic infections.

Decision-making: national authorities seeking expertise and better evidence

Initially, federal and state officials appeared to be making decisions with little or no expert advice, but physician-led initiatives have supported knowledge-sharing across states to implement control strategies on more micro levels. The Association of Public Health Physicians of Nigeria (APHPN), which has members in all states who are part of rapid-response teams and emergency operation centres at federal and state levels, has argued that locally tailored measures are needed. They say that simply adopting wholesale approaches, taken by other countries, will not suit Nigeria.

In early May, coinciding with plans to ease lockdowns, the federal Ministry of Health established the ministerial expert advisory committee on COVID-19 Health Sector Response, consisting of eminent Nigerian scientists in public health, virology and infectious disease, to assist decision-making within the ministry. The committee has been challenged to use scientific expertise and seek necessary evidence in order to “flatten the curve” without flattening the economy.

Furthermore, the new National Health Research Committee (inaugurated 8 May) could help ease the concerns that health research in the country has been uncoordinated and lacks adequate regard to policy priorities. The Committee, which includes health economics experts, will have to hit the ground running. The Minister of Health has urged them to rapidly develop a COVID-19 research agenda and identify funding sources with short-term deliverables.

Figure 2. Daily new confirmed COVID-19 cases in Nigeria (rolling 3-day average)

What next?

As Nigeria moves out of lockdown, it needs to balance controlling the spread of the disease with avoiding the worst outcomes of the response, like school closures and the crowding out of non-COVID essential health services. Adjustments to restrictions should be guided by local circumstances and supported by local actors.

Nigerian policymakers and development partners should target four areas as the country moves out of lockdown:

1. Strengthen primary health care services

As Nigeria relaxes lockdowns, community transmission might increase. Health authorities and state governors (and the international community) have a critical role in strengthening primary health care services. Their responsibilities are not only to manage the disease, but also to communicate risks and advise on individual behaviours, like social distancing and face covering, to local communities. Primary health centres are generally located in rural communities where most Nigerians live.

Existing networks of community health workers, local health centres, and community leaders should engage communities and communicate risks; structures are also needed to prevent and control infections.

2. Engage communities

Health professional organisations like the APHPN should be actively involved in guiding the response by:

- leveraging existing community structures to include (a) rapid training of health education and health promotion officers to support communication to local communities; and (b) securing the buy-in of traditional and religious leaders and other local influencers who can act as “champions” of key messages

- creating and strengthening links between the communities and local health facilities to allay community fears and ensure ongoing delivery of essential services.

3. Protecting the health workforce

Health facilities and workers need to create safe environments to manage symptomatic cases, and that means addressing shortages and supply of personal protective equipment (PPE) shortages. Unfortunately, there is not yet any coordinated mechanism to ensure supply to health facilities even though more than 800 health workers have already tested positive. Health workers need clearer guidance on how they can protect themselves. Testing and PPE (basic and N95 masks for invasive procedures) should be prioritised for frontline healthcare staff.

4. Better decisions and better data

Nigerian policymakers should ensure that COVID-19 mitigation policies that account for context specific trade-offs continue, rather than attempting to replicate models of care from high-income countries.

Careful priority-setting that incorporates cost-effectiveness evidence will be critical to ensure that limited health resources are effectively used while mitigating the risks to non-COVID-19 patients and other health system users.

The inauguration of two committees to develop the research base for COVID-19 and translate such evidence into policy recommendations are welcome initiatives. Nigerian leaders should quickly set out how these committees will interact with each other, decision makers, and other stakeholders such as local communities. Transparency should be a guiding principle.

The international community can support Nigerian policymakers and healthcare professionals by providing access to, and understanding of, the main modelling approaches informing decision making around the world, and can help provide a mechanism by which these models can be tailored to settings such as Nigeria.

Still, modelling, and international evidence more generally, will be of limited use unless supplemented and validated by local and reliable data. In its absence, community testing, combined with data on basic demographic and socioeconomic characteristics, should be implemented immediately to guide and prioritise context-specific responses.

Reliable data will be critical in ensuring that the current crisis will be managed more effectively and crucial in supporting post-COVID-19 recovery. Poor data hampering policymaking in Nigeria and elsewhere in Africa has been a longstanding issue. Countries working with international development partners should prioritise efforts to strengthen the health information infrastructure, an essential component of UHC and future pandemic preparedness.

Professor Benjamin Uzochukwu is the national chairman of the Association of Public Health Physicians of Nigeria and a member of the Ministerial Expert Advisory Committee on COVID-19 Health Sector Response.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.

Image credit for social media/web: Our World in Data