Another week, another steady stream of new evidence and analysis in education. Here are five sets of findings that struck me this week on a wide array of education topics—nutrition, accountability, violence, financing, and coherence in education systems.

-

Surprise! School meals help kids grow and learn for the kids who need it the most. It may seem obvious, but it’s worth pointing out a good study that contributes to this important field. In Ghana, a program that provided one hot meal per day for children age 5-15 (so the first 10 years of school, give or take) increased height and weight, but only for the youngest kids (age 5-8), for girls, and particularly for children living under the poverty line. Some of the same researchers subsequently found that test scores increased, particularly for girls and poor children.

A recent review of education interventions finds that “school-feeding and community based monitoring interventions are among the few programmes that are promising for improving school enrolment as well as learning.” And Sandefur and Wadhwa argue that “Fixing…schools is an intellectual and political juggernaut. Feeding kids isn't.”

-

Stay in school and don’t fight! Inviting students in violent communities of El Salvador to join an after-school club twice a week increased grades, reduced repetition, reduced absenteeism, improved attitudes towards school, and reduced both violence and misbehavior in school. At the clubs, a tutor teaches students how to solve problems and reduce violence behaviors, followed by games, science experiments, and art projects. Earlier work by one of the authors on the same after-school clubs found that “integrating students with different propensities for violence is better than segregating them,” both for the really violent kids and the less violent kids.

-

Money continues to matter in education. In the latest piece of evidence showing that resources do affect learning outcomes, a 10 percent increase in expenditures in rural, spread out schools in Texas increases reading and math scores. The benefits seem to accrue over time: “Benefits are largely concentrated among later grades, after students have had longer exposure to increased funding.” Gains are also highest in the poorest school districts. Add this to Jackson’s review of the literature on school finance in the U.S. from last year, or my quick summary of it (which comes with thoughts on how it might translate to lower income countries).

-

It's hard to do one thing well, much less two. Teachers often face two key demands: cover the curriculum and get your students to pass a test. In many countries, the curriculum and the test may be developed by different people, which puts teachers in a bind. A new analysis from Uganda shows that the curriculum and the exams emphasize “different topics and different depths of knowledge for those topics.” In a blog post, Atuhurra & Kaffenberger highlight that many school systems have coherent systems in place for enrollment, but not for learning.

-

Accountability in education: It might not mean what you think it means. Honig and Pritchett argue that there are two types of accountability. The first reports “what can be observed, verified, quantified”—think of cameras that monitor teacher attendance. The second focuses on giving an account of your performance. The former is one element in the latter. I work, for example, at an organization that cares about my attendance, but it cares much more about my overall performance, measured in ways not amenable to simple quantification. H & P argue that education is a clear example of a job where we need people to do a complex task not easy to quantify, and education technology interventions to boost accountability in education usually focus on very simple things like attendance. As Honig puts it in his summary blog post, “teachers that are likely to produce high levels of student learning and growth are likely to be repelled by a system that focuses on accounting-based accountability [the first kind I talked about] and top-down control and observation.”

Bonus reading: Here are two additional pieces of analysis, both partly by me.

-

Are female teachers better for girls? Le Nestour and I survey the evidence. In several places, female teachers do improve learning outcomes for girls (Korean middle schools; Chilean middle schools; Chinese middle schools; Indian primary schools); and in others they don’t have an effect (primary schools in Ecuador). But they often increase aspirations to go into science and math-related fields. There is little to no evidence on the impact on sexual violence in schools, but it’s an important, difficult-to-measure area and hopefully we’ll see work on this (and other ways to ensure kids’ safety) in the future.

-

How can we best help girls to succeed in school? Yuan and I discuss education challenges that are specific to girls, others that aren’t, and what it means for girls’ education investments.

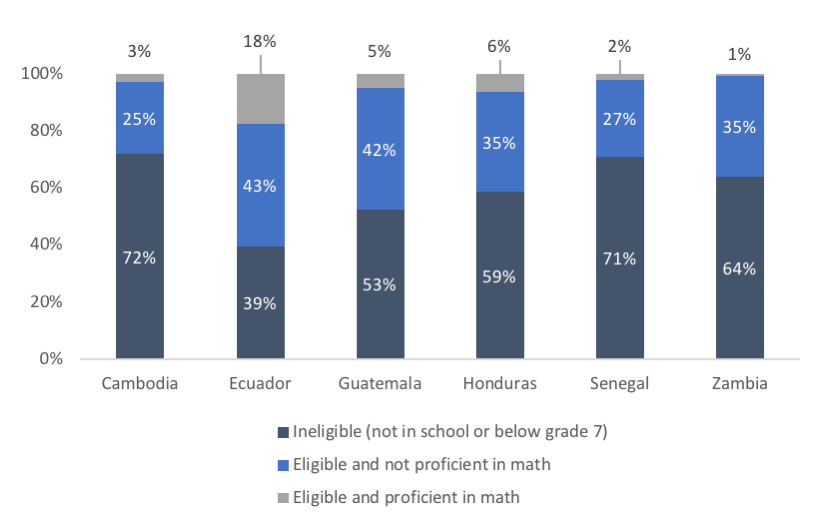

Chart of the Week: All countries that participated in the international exam “PISA for Development…fall far short of universal minimum proficiency in mathematics.”

Source: Kaffenberger 2019

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.