Recommended

As Lao Tsu put it a couple of thousand years ago, “A journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step.” One of those single steps in the journey towards a quality education—the goal of the fourth Sustainable Development Goal—is children simply attending school. While attending school regularly isn’t enough for children to learn and flourish, it’s hard to imagine them succeeding without it. Lots of studies back this up: students with lower rates of school attendance have worse academic outcomes in Chile, India (and more from India), Kenya, Mexico, Saudi Arabia, the UK, and the US. Absences are also linked to abilities less often measured in tests, like children’s executive function.

But lots of kids aren’t taking that crucial step. Student absences from school are high in many countries. When visitors took attendance at schools in Madagascar, Nigeria, and Uganda, one in every four students was missing. In Mozambique, more than half of students were missing. And that’s when the schools knew the visitors were coming! When students learn only half as much in a year of education in some countries as they do in others, just getting students to school regularly seems like one of the first things to fix. (Making sure teachers are at school consistently is another important fix, but that’s for another blog.)

Measuring student attendance accurately certainly isn’t the solution to widespread absenteeism, but it’s an essential part of any solution. You can’t identify the pupils who are consistently missing school and so are at risk of dropping out without measurement. And researchers can’t test whether interventions to boost student attendance have worked without measurement.

How to measure student attendance

So how do you measure student school attendance (or its inverse, absenteeism)? In our new study in the Economics of Education Review, we looked at dozens of recent studies that measure student absenteeism. They do it lots of different ways (Table 1): sometimes they just rely on school records (you know, where a teacher notes down whether a student is present or absent). Other times they send an enumerator to a school unannounced so that the school can’t make a special effort to get kids there (i.e., spot checks). Sometimes they just ask parents or students. Unannounced spot checks are likely the most accurate measures, but they’re also among the most expensive to do.

Table 1. Seven ways that recent studies measure student school attendance (no judgment until the next section)

|

Use existing school records |

|

Have enumerators take attendance during unannounced visits (i.e., spot checks) |

|

Schedule visits to measure absenteeism |

|

Ask students |

|

Ask parents |

|

Scan students’ fingerprints |

|

Ask teachers or principals for their impression of attendance trends |

Next level: how to measure student attendance accurately

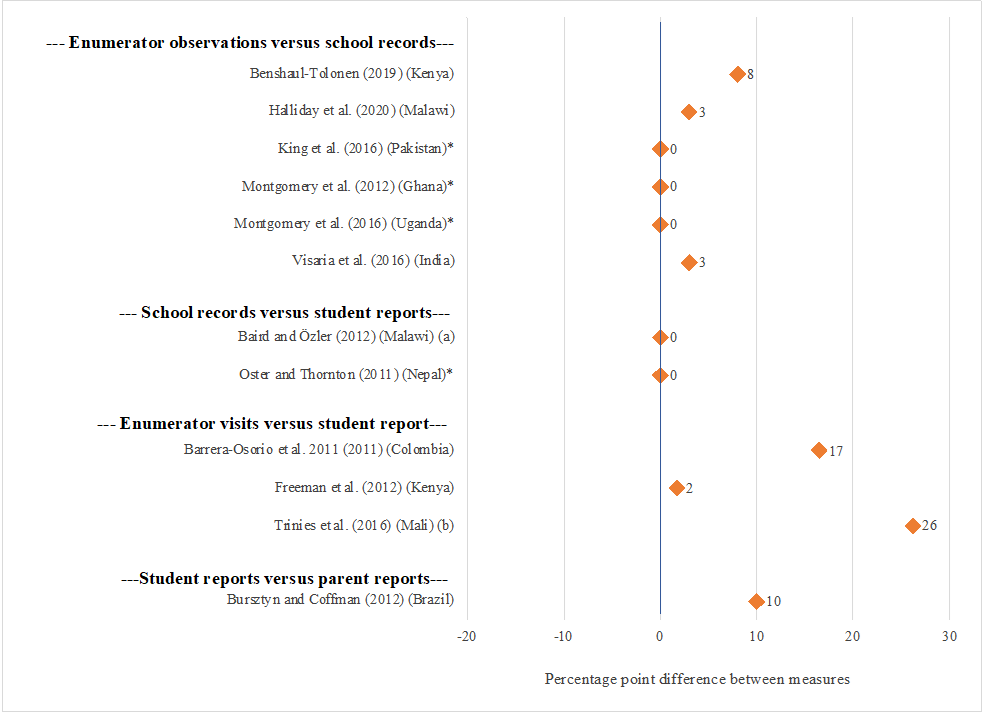

We also look at dozens of (okay, a dozen and a half—17) studies that compare different methods of measuring student absenteeism. So in the same study, they measure absenteeism at least a couple of different ways and look at the differences in results. Here’s what we learned (Figure 1).

-

Unannounced spot checks tend to reveal the highest levels of absenteeism. But in five of the six studies that compare unannounced spot checks to school records, five of them gave estimates of within five percentage points of each other. In other words, school records are often (but not always) accurate. You just may need to do a few spot checks at the beginning of the year to see. In Malawi, researchers discontinued spot checks after they confirmed that school records were doing the trick.

-

Students understate their absences from school. It may not come as a shock that students don’t want to admit the degree to which they miss school. But that means that relying on their reports of their school attendance can muck up measurement. In Colombia, student reported attendance was 17 percentage points higher than what enumerators visiting school found. If researchers had relied on student reports, the estimated impact of the program on reducing absenteeism would have been half its actual size. (Since school attendance is capped at 100 percent, big overreporting compressed the difference between the program participants and the comparison group.)

-

Parents understate their children’s absences from school even more than children do. In another surprising twist, parents don’t always know what their children are doing. In Brazil, parents’ estimates of their children’s school attendance were ten percentage points lower than their child’s estimates.

Figure 1: How much more absenteeism does this method measure than that method?

This isn’t all the estimates from the paper, but it’s all the ones we could figure out how to put on a plot.

But wait: there’s more to keep track of!

If you’re measuring absenteeism, here are other issues to keep in mind:

-

How much will it cost? Existing school records are cheaper than enumerator spot checks, but in places where school records are of poor quality or where teachers have an incentive to understate absenteeism, it may not be worth the tradeoff. (One research team in Uganda invested in training schools on how to improve their recordkeeping.)

-

Why are the pupils missing school? To take action on reducing student absences, you have to know why they’re absent. Is it because the teachers aren’t showing up? Or because they’re helping with the harvest? But be careful: people aren’t any more likely to be honest about the reasons for missing school than they are about missing school in the first place.

-

If it’s a survey, how do you frame the question? Do you ask about attendance or absence? Do you ask about absences in the last week or the last month? Do you record absences by full day or half day (to capture the kids who don’t come back after lunch, as captured in one study in Nigeria).

-

Beware the days of the week and the seasons! In some cases, pupils miss school most during the harvest season. In others, they miss school on market days. Measure of absenteeism have to be spread across the week and across the school year to capture an accurate picture.

-

Are lots of students missing a little or are a few students missing a lot? If the goal of the measurement is to evaluate the impact of a program, then class or school-level absenteeism measures may suffice. But if the objective is to use the attendance data to intervene with youth who may be struggling, then student-level measures are important to capture which kids are consistently missing and so are at greatest risk of dropout.

We explore all of these issues and others in more detail in the paper.

Measuring student absenteeism isn’t simple. But it’s a crucial first step—just the first step—in making sure every child enjoys the benefits of consistent school attendance.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.

Image credit for social media/web: nuttapon / Adobe Stock