Recommended

Girls’ education remains a high priority for international organizations and for governments and non-government organizations in low- and middle-income countries, as it should be! There are many countries in the world where girls lag behind boys in either access or performance, and gender discrimination in the labor market may nudge policymakers to boost girls’ education even after parity in educational access has been achieved, in order to get closer to gender equality in later life outcomes.

There is also increasing evidence on effective interventions to expand girls’ access to education and improve their learning outcomes when they are in school. At this point, reviews of “what works” in education are a literature all their own. (We even wrote one ourselves; oh yeah, and part of another one!)

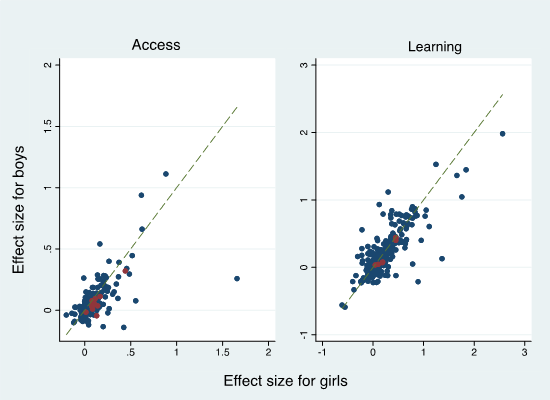

Yet much of the research evaluating the impact of programs draws conclusions from pilot programs implemented with a few hundred or a few thousand girls, often through nongovernment agencies. While we gain important insights from those pilots, they don’t tell us what’s possible to implement at large scale. In our new working paper—“Girls’ Education at Scale”—we review almost 100 studies from around 40 countries on programs and policies that reach at least 10,000 students and also report on final school outcomes such as completion and student learning (Figure 1). We focus on those outcomes, not because they’re the only ones that matter (they aren’t!) but because completing school and learning in school both deliver returns in girls’ lives. Here’s what we learned.

Figure 1. Map of the countries where the large-scale interventions to improve girls’ education have been implemented

What has worked for girls’ education at scale?

1. Making school cheaper (i.e., eliminate fees, provide scholarships, feed children, or provide cash transfers)

Many countries have eliminated school fees especially for primary schools, but school materials, transportation, mandatory school “contributions”, and opportunity costs (e.g., the need to provide care for younger siblings) still keep girls from attending school. Large-scale programs that provide scholarships and vouchers or eliminate fees (with some programs benefitting more than 100,000 girls) all increased test scores, improved secondary school completion rates, reduced dropouts, and also reduced pregnancies in female students. Large-scale school meal programs in 32 African countries boosted enrollment, while similar programs in Ghana (now integrated into the government budget) and India improved test scores, with the biggest effects on girls. Cash transfers have been effective in boosting enrollment, but less so in boosting test scores.

2. Making schools more accessible

Building schools close to where girls live in Burkina Faso improved enrollment (predictably!) and test scores. Ten years later, girls’ completion rates in beneficiary villages were twice as high as in comparison villages, and marriage rates were much lower. And we know these effects persist even longer. A school construction program in the 1970s in Indonesia built over 60,000 schools: more than four decades later, not only are women in the target areas more likely to complete primary school, but their children are also more likely to complete secondary and even tertiary schooling (with slightly bigger effects for daughters!).

3. Teaching better

General improvements in the quality of instruction carried out by providing detailed teachers’ guides, reading materials for students, and coaching teachers in Kenya, in Pakistan, in Laos and Zambia, and in India all led to improvements in numeracy and literacy, although some programs experienced challenges as they scaled up nationally, such as teachers receiving less coaching during scale-up than initially planned. Remedial programs that target children who fall behind, such as programs that hire young women or teaching assistants with no previous experience as tutors, summer reading camps, grouping leaners by ability instead of grade levels, and combinations of these interventions, led to significant gains in student learning. Large-scale teacher performance incentives were also generally effective in raising test scores, sometimes with gains larger for girls than boys. Both large-scale teacher professional development programs and ed-tech interventions designed to improve instruction have a more mixed record, with some interventions more successful than others.

4. What about explicitly addressing gender barriers?

Some interventions focus on barriers inherently affecting girls, but most of these interventions have not been evaluated for final educational outcomes like school completion or learning. That doesn’t mean they aren’t important. Their primary goals—to protect girls, to boost their overall well-being, or to prepare them for life after school—are important both on their own merits, and as necessary steps in getting girls to benefit from schooling. A national school latrine construction program in India led to strong enrollment impacts that endured at least three years after. Gender-sensitization trainings in several countries led to improved reported views on gender norms, some self-reported behaviors, and measures of leadership and self-confidence. Large-scale programs that provided safe spaces and mentoring for girls (one of the programs reached almost 100,000 girls in nine countries) led to positive outcomes such as reduced adolescent pregnancy and improved re-enrollment rates after disruption in schooling.

Where do we need to know more?

One of the most frustrating limitations of reviewing the evidence is realizing how much we still don’t know! Some interventions have been implemented at scale but have only been evaluated in a few settings, such as providing eyeglasses to students or improving mothers’ literacy. Other interventions have more limited or mixed evidence of effectiveness for girls’ education specifically, such as providing information on returns to education or facilitating community monitoring and school accountability. In our paper, we compare the conclusions across five different reviews of what works for girls’ education and far too many categories (including some crucial to girls’ well-being, like menstrual hygiene management and school-related gender-based violence) simply have “not enough studies,” and that’s even more true when we’re talking about studies carried out at scale and including longer run educational outcomes.

Takeaways

There are proven ways to expand girls’ access to education and to improve its quality at scale. Some of these are relatively simple (but not cheap) interventions, like making school cheaper and making school more accessible. Others involve lots of moving parts, like improving the quality of instruction, but we have examples of countries that have pulled it off.

Any broad, international view of the evidence—like this one—should be the beginning (or in this case, the middle) of a conversation, not the end of it. Girls in different countries and at different levels of education face different obstacles. For example, absenteeism due to menstruation may be high in Bangladesh and India but low in Kenya and Nepal. In some countries, the cost of schooling may not be a major obstacle in primary but a major obstacle in secondary. Every country will need to choose its best bets for helping girls to succeed.

But evidence of what has worked at scale in a variety of settings can provide an essential starting point for that discussion, pointing both to possible interventions and to where countries can innovate and test, providing the next generation of evidence for girls’ education.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.

Image credit for social media/web: Center for Global Development