Recommended

The European Union (EU)’s arsenal of development finance instruments comprises grants, budget support, blends of grants and loans, guarantees, and trust funds. But little attention has been paid to its macro-financial assistance (MFA) tool. Since the 1990s, it has been deployed to help countries in the EU neighbourhood that face balance-of-payment crises. Recently, a special MFA+ instrument of EUR18 billion was deployed in the form of highly concessional loans with long maturities to provide immediate finance assistance to Ukraine.

But why is this instrument confined to the EU’s neighbourhood, particularly when multiple low- and middle-income countries are suffering from extensive financial gaps exacerbated by the economic shocks of the pandemic and the war in Ukraine, and many are unable to finance immediate needs? We set out to explore the potential for the instrument to be expanded to countries beyond the EU neighbourhood.

What is MFA?

The MFA instrument was created in 1990 to help prospective EU Member States from the eastern European blocs to overcome balance of payment issues. Since then, it has expanded to counties covered by the European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP)—16 countries to the South and East of the EU’s borders—with the objective of “restoring a sustainable external financial situation, while encouraging economic adjustments and structural reforms.” The instrument usually consists of medium to long-term concessional loans but can also take the form of grants. It requires the approval of both European Parliament and the Council on a case-by-case basis following a proposal by the European Commission.

There are strict criteria for countries to be able to benefit from MFA:

- The country must have a previous credit arrangement in place with the IMF to alleviate short-term balance of payment difficulties and implement adjustment measures.

- There must be a significant and residual external financing gap over and above the resources provided by the IMF and other multilateral institutions, despite the implementation of strong economic stabilisation and reform programmes by the relevant country.

- The country must respect effective democratic mechanisms, including a multi-party parliamentary system and the rule of law, and guarantee respect for human rights.

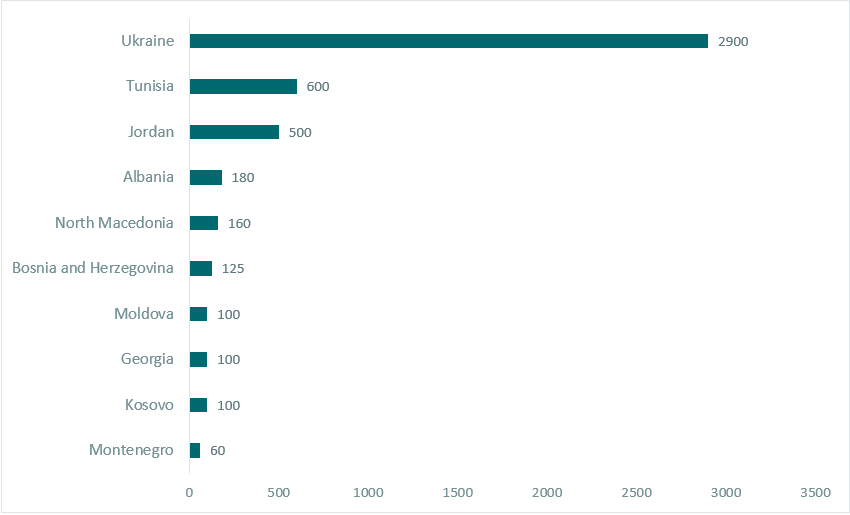

As illustrated in Figure 1, MFA has been concentrated in three regions at the borders of the EU: the Western Balkans and the Eastern and Southern neighbourhoods. Between 2020 and 2022, 10 countries have benefited from MFA disbursements of a total of EUR4.8 billion. In 2020, the EU adopted a special package to support countries in dealing with the economic consequences of the pandemic. Although the European Parliament and Council stated that MFA “should be an exceptional financial instrument […] of short-term nature,” in practice the programmes are often rolled over. Jordan and Georgia received three successive MFA programmes over the last ten years, while Ukraine benefited from four before Russia’s invasion in 2022.

Regarding its financing, the MFA is provided through the EU using its high-rating profile to borrow from the financial markets at favourable terms to then lend on to partner countries. The loans are guaranteed by the External Action Guarantee (EAG) with a provisioning rate of nine percent. The EAG, of a maximum amount of EUR 10 billion between 2021-2017, is also used to support operations under the European Fund for Sustainable Development Plus (EFSD+).

Figure 1: Disbursements under EU Macro-Financial Assistance, 2020-2022, EUR Million

Source: European Commission.

Note: Figure 1 includes disbursements until the end of 2022. In November 2022, the EU adopted the MFA + for Ukraine of a total of EUR18 billion. Under this package, EUR9 billion have already been disbursed. In 2023, the EU adopted an additional EUR145 million MFA for Moldova to be disbursed this year.

Acute global economic situation

Today, macro-economic issues are by no means limited to the immediate vicinity of the EU. The succession of shocks—the pandemic, supply constraints, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, soaring inflation and tightening monetary and financial conditions—have adversely affected dozens of low- and middle-income countries. Countries such as Sri Lanka, Ghana and Pakistan are all facing acute balance of payment crises and are negotiating with the IMF to avoid default. With rising interest rates across the globe, other will undoubtedly follow.

In response, IMF lending has sharply increased over the last three years, with the total rising from SDR73 billion (USD 96 billion) in 2019 to an all-time high of SDR113 billion (USD 149 billion) in April 2023. Currently, 94 countries have credit arrangements with the IMF. Funding through the Poverty Reduction and Growth Trust (PRGT) for low-income countries has more than doubled over the last three years. However, given the urgency of immediate needs, current resources for the PRGT remain insufficient.

MFA to the rescue?

Can the EU expand the geographical scope of the MFA? In fact, there are precedents of expanding the tool to countries outside of the EU neighbourhood. Between 2005 and 2007, the EU provided MFA to Tajikistan and between 2015 and 2016, to the Kyrgyz Republic, both of which were not covered by the ENP. The ex-ante evaluation of the MFA to the Kyrgyz Republic justified the provision of MFA by the “the strength of the political and economic reform momentum in the country and by its position in a region of strategic economic and political importance for the EU.”

In table 1, we identify 23 low- and lower-middle income countries which would currently meet the eligibility criteria for MFA. Each has agreed IMF programme resulting from a balance-of-payment crisis, and each meets the standards of human rights and democracy of MFA-eligible countries.

Table 1: Low- and lower-middle income countries under an IMF program and considered at least “partly free” by the Freedom House Index

|

Cabo Verde |

Liberia |

Sao Tome & Principe |

|

Cote d'Ivoire |

Madagascar |

Senegal |

|

El Salvador |

Malawi |

Sierra Leone |

|

The Gambia |

Mongolia |

Solomon Islands |

|

Ghana |

Nepal |

Sri Lanka |

|

Honduras |

Niger |

Vanuatu |

|

Kenya |

Papua New Guinea |

Zambia |

|

Lesotho |

Samoa |

|

Source: Author’s elaboration based IMF data and Freedom House.

Note: With the exception of Jordan, all countries currently benefiting from MFA are classified as “partly free” in 2023 by the Freedom House Index. Ukraine and Bosnia and Herzegovina ranked the lowest in political rights and civil liberties with a score of 4 for each indicator. These scores were used as a “minimum floor” of tolerance to establish the list in table 1.

MFA is a tool that has proven to be efficient in both fostering macroeconomic stabilisation and promoting structural reforms. With a constrained EU development budget combined with spiralling needs across the globe, and to avoid a cascade of defaults in low- and middle-income countries, the EU could consider expanding the use of MFA to a select number of countries outside of its neighbourhood.

The tool is there. All that’s needed now is the political will.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.

Image credit for social media/web: EwaStudio/Adobe Stock