Funding for overseas aid is under fire. And more shots are sure to come. Politicians will be questioning aid’s effectiveness and value, perhaps reshaping aid to stress domestic interests.

So it’s a good moment to remember: Development cooperation goes way beyond sending money. Aid is important. But we have barely explored the potential for innovative, non-aid cooperation to offer mutual benefits for richer and poorer countries.

Here’s exactly what we mean: a small pilot project between the US and Haiti showed that the US could directly and effectively assist Haitian families to earn dignified livelihoods—at negative cost to US taxpayers. That is, the two countries could cooperate for development in a way that actually adds value to the US economy. It did this with short-term work visas.

In 2010, one of us (Clemens) proposed a new idea to help Haitians recover from that year’s devastating earthquake: open up limited new channels for lawful mobility between the two countries. Over the course of five years, this idea became a reality: first when the US Department of State made Haitians eligible for temporary work visas with bipartisan support, and next with a pilot project matching Haitian farmers with unfilled agricultural jobs in the United States.

Watch a US farmer and a Haitian farmer describe in their own words how this program has benefited both of them, and both countries:

We recently conducted an impact evaluation to assess the project’s impact on both the Haitian and US economies, now forthcoming in the peer-reviewed IZA Journal of Labor and Development. A recent piece by The Economist explains what we found:

A new study by Michael Clemens and Hannah Postel of the Centre for Global Development compares those Haitians who secured visas through the project with unsuccessful applicants left behind. The benefits were mind-boggling: the temporary migrants earned a monthly income 1,400 percent higher than those back in Haiti. Most of their earnings flowed back home in the form of remittances. For comparison, a 10–30 percent raise would normally be cause for celebration.

The sample for the study was small. But its findings match those for a similar scheme that offered temporary agricultural work in New Zealand to people from Tonga and Vanuatu. That policy was assessed by economists at the World Bank as “among the most effective development policies evaluated to date”.

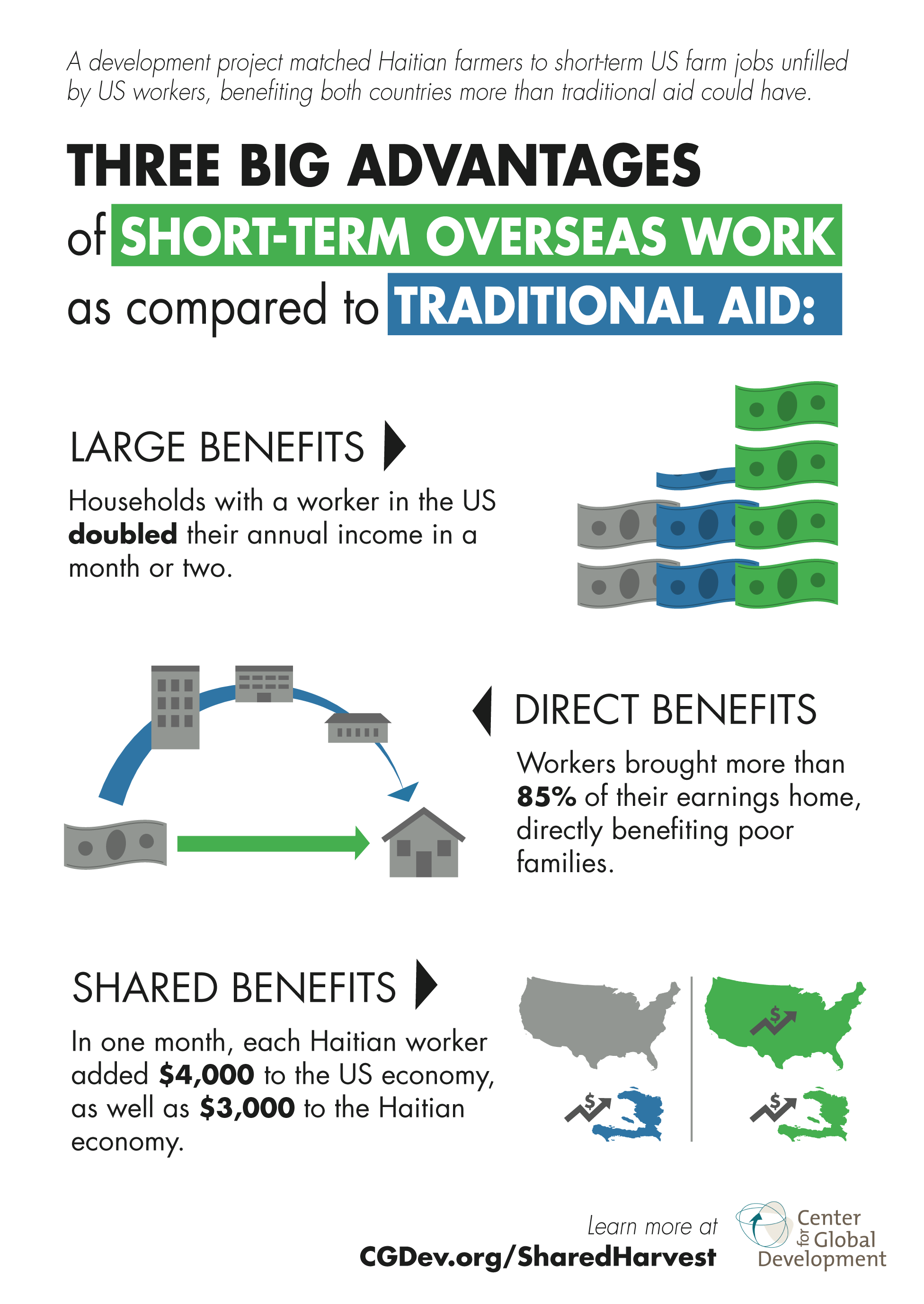

But that effectiveness for Haitians is just the beginning. We find that granting temporary work visas to people from developing countries has three major benefits compared to traditional foreign aid. It is larger: Haitian households with a worker who traveled to the US doubled their annual income in just a few months. It is more direct: workers brought more than 85 percent of their earnings home. And it also benefits the United States: in one month, each Haitian worker added $4000 to the US economy.

These results suggest large unexplored potential in fostering temporary labor mobility to benefit rich countries while effectively assisting the poor overseas. Such a program checks all the boxes for politicians expected to prioritize donor-countries’ national interest and cost-effectiveness in setting strategy for development cooperation.

This is not a call to replace aid. It’s a call to innovate, to break the mold and test out new ways of doing development cooperation: new and more effective forms of aid, new and more effective ways to cooperate without aid. Traditional aid may be entering something of a crisis. But crises have an upside if they push us to open up new possibilities.

El financiamiento para la asistencia exterior se encuentra bajo fuego. Y más fuego seguramente vendrá. Los políticos cuestionarán la eficacia y el valor de esta asistencia, tal vez reformulándola para enfatizar intereses nacionales.

Por lo tanto, es un buen momento para recordar: la cooperación al desarrollo va mucho más allá del envío de dinero. La asistencia es importante. Pero apenas hemos explorado el potencial de una cooperación innovadora y sin asistencia para generar beneficios mutuos a los países más ricos y pobres.

Esto es exactamente lo que queremos decir: un pequeño proyecto piloto entre los EE.UU. y Haití mostró que EE.UU. podría asistir de manera directa y efectiva a las familias haitianas a obtener calidades dignas de vida--a un costo negativo para los contribuyentes estadounidenses. Es decir, los dos países podrían cooperar para un mayor desarrollo de una manera que realmente agregue valor a la economía de los EE.UU. Este piloto lo hizo con visas de trabajo Temporales.

En 2010, uno de nosotros (Clemens) propuso una nueva idea para ayudar a los haitianos a recuperarse del devastador terremoto de ese año: abrir nuevos canales limitados para una movilidad legítima entre los dos países. En el transcurso de cinco años, esta idea se convirtió en realidad: primero cuando el Departamento de Estado de EE.UU. hizo que los haitianos tuvieran derecho a visas temporales de trabajo con apoyo bipartidista, y luego un proyecto piloto que ofreció trabajos agrícolas a agricultores haitianos en vacantes en EE.UU.

Observe cómo un agricultor estadounidense y un agricultor haitiano describen en sus propias palabras cómo este programa ha beneficiado a ambos, y a ambos países:

Recientemente realizamos una evaluación de impacto para evaluar el impacto del proyecto en las economías haitiana y estadounidense, el cual se publicará en el IZA Journal of Labour and Development. Un artículo reciente de The Economist explica lo que encontramos:

Un nuevo estudio de Michael Clemens y Hannah Postel del Centro para el Desarrollo Global compara aquellos haitianos que obtuvieron visas a través del proyecto con los solicitantes que no las obtuvieron. Los beneficios fueron increíbles: los inmigrantes temporales ganaron un ingreso mensual 1 400 por ciento más que aquellos en Haití. La mayor parte de sus ingresos retornaron a su país en forma de remesas. Como comparación, un aumento de 10-30 por ciento sería normalmente un motivo de celebración.

La muestra del estudio fue pequeña. Pero sus hallazgos coinciden con los de un esquema similar que ofreció trabajo agrícola temporal en Nueva Zelanda a personas de Tonga y Vanuatu. Esa política fue evaluada por los economistas del Banco Mundial como "entre las políticas de desarrollo más eficaces evaluadas hasta la fecha".

Pero esta eficacia es sólo el comienzo. Encontramos que la concesión de visas temporales de trabajo a personas de países en desarrollo tiene tres beneficios importantes en comparación a la asistencia externa tradicional. Genera más ingresos: los hogares haitianos con un trabajador que viajó a EE.UU. duplicaron sus ingresos anuales en pocos meses. Es más directo: los trabajadores trajeron de regreso más del 85 por ciento de sus ingresos a sus hogares. Y también beneficia a EE.UU.: en un mes, cada trabajador haitiano agregó $4000 a la economía estadounidense.

Estos resultados sugieren un gran potencial inexplorado en el fomento de la movilidad laboral temporal para beneficiar a los países ricos, lo cual al mismo tiempo asiste eficazmente a poblaciones pobres en el extranjero. Tal programa satisfaría a los políticos que priorizarían el interés nacional de los países donantes y la relación costo-efectividad para el establecimiento de una estrategia de cooperación para el desarrollo.

Esto no es una llamada para reemplazar a la asistencia. Es un llamado a innovar, romper el molde y probar nuevas maneras de cooperar para el desarrollo: formas nuevas y más efectivas de asistencia, formas nuevas y más efectivas de cooperar sin asistencia. La asistencia tradicional podría estar entrando en una crisis. Pero las crisis tienen un lado positivo si nos empujan a abrir nuevas posibilidades.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.