Recommended

Blog Post

With more than 1.5 billion students are out of school, COVID-19 school closures could exacerbate existing inequities. In this post we analyse what we know (so far) about some of the drivers of inequity—and measures taken to address them—in different countries, using our open-access database. The database is a work-in-progress and comments and corrections are very welcome to shares@cgdev.org and lcrawfurd@cgdev.org.

Poorer students are likely to be less able to access distance learning opportunities

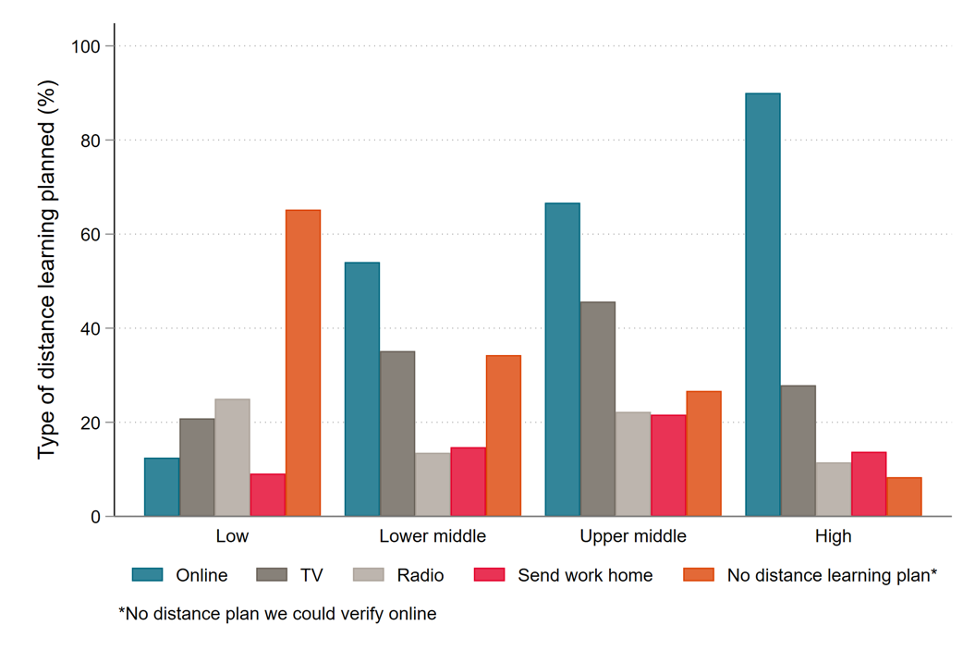

In a previous post, we showed that richer countries are more likely to offer distance learning programs—90 percent of high-income countries are providing some kind of distance learning program for their students while only 29 percent of low income countries are. At the same time, poorer children in countries that do have distance learning programs—in both high- and low-income countries—tend to be less able to access them and may fall further behind if additional support is not made available.

Figure 1. Type of announced distance learning measure (updated from previous post)

Source: authors’ analysis of CGD database

Online learning programs may be most likely to drive inequity

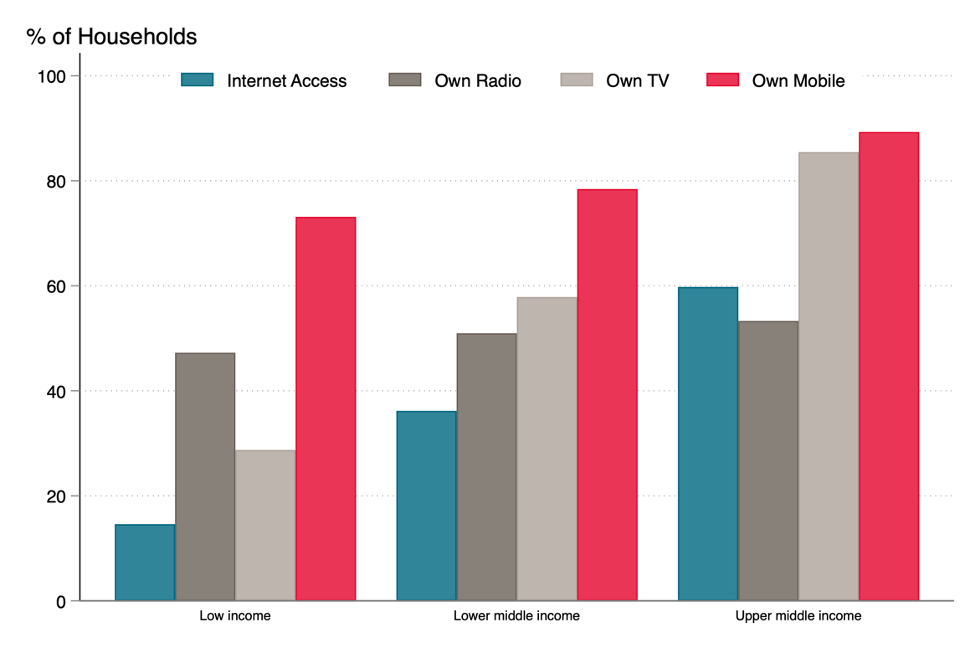

Online learning is the most common form of distance learning emerging as countries transition to remote strategies. Yet in low- and lower-middle income countries, less than 40 percent of households have access to the internet. And this is a challenge in rich countries too: around 12 percent of households in the US are not connected to the internet, with some US counties reporting household broadband access under 40 percent (US Census, 2019).

Online learning also raises questions about disability and gender equity. Globally, nearly 25 percent fewer women have access to the internet than men, and in sub-Saharan Africa, women are 50 percent less likely to use the internet than men (World Bank, 2016). We have not identified any country with specific gender-based concerns or considerations in their online learning plans.

While creating distance learning programs that are accessible for children across all disabilities may be almost impossible, particularly in the short-term, only a few countries have noted any plans for ensuring accessibility for students with special needs. A handful of countries have announced special measures for children with disabilities who are not able to access online learning. For example, in Qatar, lessons will be broadcast in sign language, and in Latvia and Ireland, special education institutions are developing their own plans for distance learning. Ten other countries have also announced plans to virtually address the needs of students with disabilities.

Additionally, in Latvia and Lithuania, governments are actively seeking ways to provide students with technology and connectivity they may lack to ensure that disadvantaged students don’t miss out on learning during school closures. Others, like Malaysia, have suggested students who are unable to access distance learning rely on their textbooks. It is unclear what the implications of assigning alternate, and potentially lower-quality, work to already marginalized students will be in the long term.

Many countries are making efforts to reach a broad range of learners through multiple modalities.

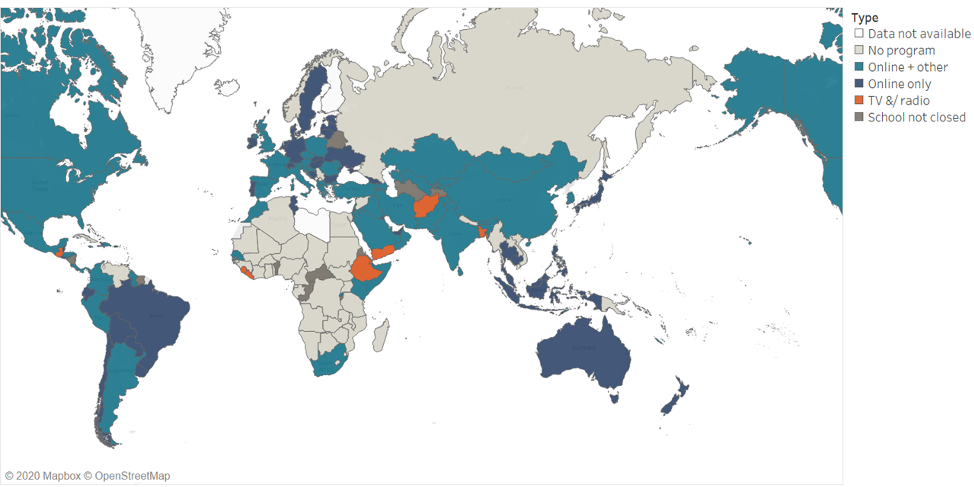

About 60 countries have announced plans to use multiple forms of media. By offering learning opportunities through radio and television in addition to online strategies, countries may increase the likelihood that they’ll be able to reach a broad and diverse constituency of students. But as the map below shows, there is a striking absence of plans to pursue any form of distance learning across sub-Saharan Africa, much less the multiple channels needed to reach the greatest number of students.

Figure 2. Mode of distance learning delivery by country

Source: authors’ analysis of CGD database

* Some countries coded as ‘Online+’, including Canada, the UK, and US do not have centralised distance learning strategies. Whether and how students have access to distance learning in these countries can vary substantially by location.

Language and parent literacy rates may further drive inequities

In most cases, distance learning materials are available in a country’s national language. In countries like South Africa, which has 11 official languages, children in homes which do not speak the national language will be less likely to access learning during school closures. We identified just 15 countries—including Kenya—that are offering radio or television instruction in more than one language. It is challenging for governments to produce materials in multiple languages, particularly in a crisis situation. Yet the longer schools remain closed, the more important it is that strategies are implemented to reach all children in linguistically diverse contexts.

Nearly all countries have called on parents to support home-based learning, and at least 55 countries are providing guides for parents to support their children while they are learning at home. Parents’ ability to provide support will of course be shaped by their own educational attainment, literacy, language, and work obligations. The Government of Ethiopia, for example, has informed parents that they are expected to support their children to learn from home. This will be particularly challenging for the nearly 50 percent of adults who are illiterate.

Beyond learning: not going to school every day will have a disproportionately adverse effect on poorer children

We coded posts from the social media pages of ministries of education in our database. Many were filled with advice to families about non-educational issues: sanitation, prevention of transmission, coronavirus-related healthcare, and advice for how to support children’s socioemotional wellbeing during a crisis. Schools play vital roles in community support, social protection, nutrition, and public health, and some countries are planning to implement policies that cater to these needs while schools are closed.

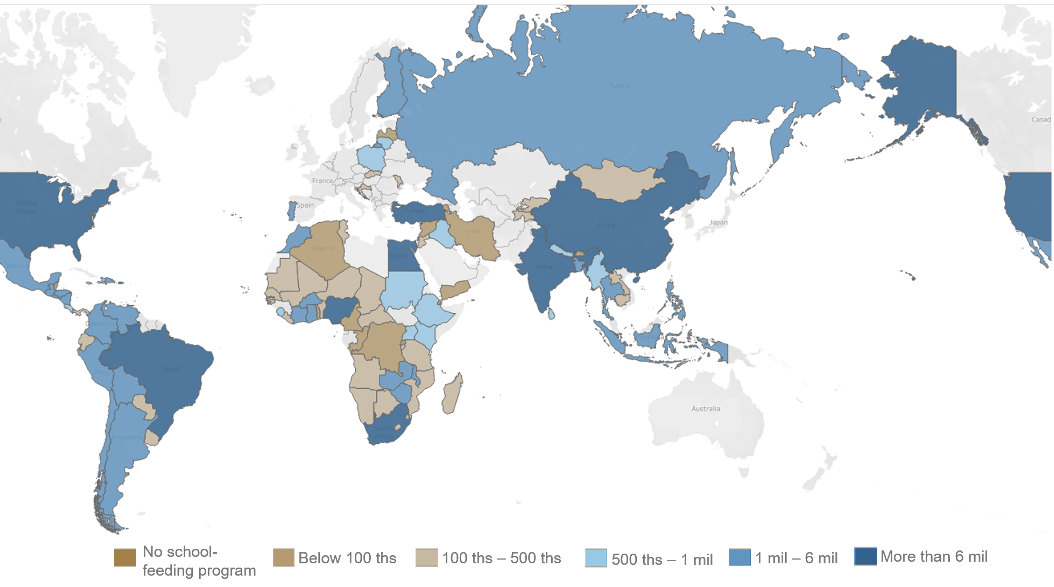

Hundreds of millions of kids get meals at school. While several countries are continuing to provide food for students normally eligible for free school meals, many are not. In Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Lesotho, Hungary, South Africa, and parts of India, school meals will be delivered to those who would have had them at school. In El Salvador, schools were encouraged to send food and school supplies home with families before closing. Some countries are offering food vouchers to families of children who otherwise receive school meals.

As our colleague Dave Evans noted, widespread school closures can pose disproportionate risks for young women and girls. So far, few countries have announced plans for protecting vulnerable girls during closures. South Africa has advertised the provision of “Dignity Packs” including sanitary pads for girls in need. Palestine is offering online psychosocial support to students and families, including covering gender-specific concerns and discrimination.

If you know of other policies in place to protect girls, please do let us know.

For students living in fragile and conflict-affected states, COVID-19 may manifest as a “crisis within a crisis.” Thirteen of the 16 countries classified as experiencing high- or medium-intensity conflict have announced nationwide closures. Of these, only four (Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, and Yemen) have plans for distance learning or other forms of student support. Both boys and girls in fragile and conflict-affected states may face additional risks as schools close, including increased susceptibility to child labour, sexual exploitation, and recruitment to armed groups.

To date, education response plans have generally not addressed additional needs of those living in conflict settings or of refugees. In Bangladesh, makeshift schools serving refugees have been closed. In Lebanon, Syrian refugees are missing out on meals normally provided in schools and nongovernmental organization programs supporting psychological wellbeing have largely been paused. To our knowledge, only Armenia has announced specific provisions for refugees by making in-kind benefits and food vouchers available to Syrian refugees. Failing to address the needs of those living in conflict-affected contexts during a global health crisis—a crisis within a crisis—could have lasting consequences.

Many parents, particularly those who work in hourly or informal jobs, don’t have the option of working from home and—without social protection policies—are likely to face significant economic shocks. Thirty-three middle- and high-income countries are supplementing existing cash transfer programs, while several others are offering one-time cash grants to support families in need. At least 10 countries—but (as far as we know) none in sub-Saharan Africa—are offering cash transfers for those working in the informal sector. Without additional financial and childcare support, the most vulnerable families face increased risk in the midst of school closures and livelihood uncertainty that has the potential to make it more difficult for children to return to school when classes resume.

Moving forward

As this crisis continues, countries need to consider how to mitigate the negative effects of keeping schools closed, particularly for the most vulnerable. The goal must be to help students learn, stay safe, and be adequately fed, whilst keeping them and people around them safe from the virus. It is critical to consider what can be done now and in the future as education systems move toward recovery in order to ensure that most vulnerable are not left behind.

Thanks to Laura Moscoviz for her assistance on this blog post.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.