The UK will have a general election by January 2025, most likely in autumn 2024, perhaps close to the US presidential election.

The polls suggest a potential wipe-out for the ruling Conservative party, who have been in government since 2010. A majority in the House of Commons looks likely for the Labour Party, though it can’t be taken for granted and may be much smaller than the polls suggest. Although some kind of Labour majority seems the most likely outcome, it is important not to dismiss the potential for a coalition (e.g. Labour-Liberal Democrat) government if there isn’t a majority for any party.

If there is a new government, things couldn’t look much more different to 1997 when Labour was elected, and the UK’s Department for International Development (DFID) was launched.

Domestically, the incoming government faces a country falling to bits, in some cases literally (crumbling concrete in schools, hospitals, universities, airports, and other public buildings); a Brexit process only just about to be fully implemented with knock-on impacts on food prices coming soon.

Crucially, the fiscal situation looks bleak but is little discussed—leading institutes argue no parties are being open with the public about what is to come.

In the UK context the main discussion of UK development policy amid all of these headwinds has been around the current government’s new ‘white paper’, which seeks to set UK development policy to 2030 and tried to be cross-party. That said, it could have a very short shelf life as presumably any incoming government, especially one with a reasonable majority, would want to set out its own brand or agenda.

So, what has changed since 1997 when DFID was established by the new Labour government and what will the incoming government inherit in terms of UK development policy?

What’s changed since 1997?

In 1997, the incoming government faced a benign context, both fiscally and globally. The global context for development cooperation post-pandemic is the exact opposite.

Globally, there is the new geopolitics dynamics of conflict in Ukraine and the Middle East. The rise of populist nationalism, rolling back of democracy in some countries as well as declining public support for democracy in some regions. Possibly a second Trump presidency. Weak support for multilateralism. And the window for smoother transitions to adapt to climate change that is already ‘baked in’ is narrowing.

In short, the post-pandemic world presents a challenging environment for development cooperation. Most urgently, post-pandemic debt servicing is offsetting a significant portion of Official Development Assistance (ODA), with the ratio of debt servicing to ODA reaching a third or more in some of the world’s poorest countries, judging by a quick look at World Bank data.

The real debt crisis isn’t only the potential for financial crises though that is there, but the silent crisis of debt repayments and austerity measures squeezing out social and productive expenditures.

At the same time economic growth in many developing countries is weak and economic development stalled or proceeding at snail’s pace, with the real possibility of the end of the manufacturing pathway to development. Further, the poverty-related SDGs will not be met on current trends.

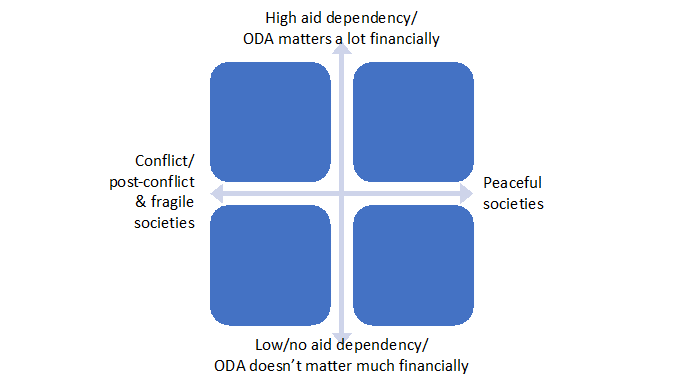

What has really changed though, in the Global South over the last 30-40 years is the emergence of a dual polarisation, first between countries where aid is essential for the government to function and deliver basic services and many countries where traditional aid just doesn’t matter anymore, due to expanding domestic resources. Then there is a second, off-cited polarisation between conflict/post-conflict and peaceful countries.

That makes four contexts (see figure below):

- countries where ODA does matter a lot and are in conflict/post-conflict situations.

- countries where ODA does matter a lot and are not in conflict/post-conflict situations.

- countries where ODA does not really matter and are in conflict/post-conflict situations.

- countries where ODA does not really matter and are not in conflict/post-conflict situations.

Traditional ODA caters for 2 of the 4 places—the ODA matters onesbut that is home to half of global extreme poverty. So, what about the places where ODA doesn’t really matter and the other half of global extreme poverty? There is much that development cooperation can do and does do in places where ODA matters less, and it is not necessarily about spending large sums of money. Potential avenues are policy coherence (e.g. trade policies or supporting new global tax rules), or supporting more open policy processes (though this can look like political meddling); or widening the evidence base in policy making, bringing evidence from other contexts and supporting national think tanks, technical assistance (though note the loss of UK expertise in FCDO that was reported by the Independent Commission on Aid Impact) and co-financing global and regional public goods.

Figure 1. Four contexts for development cooperation

Second, what will the new government inherit?

The UK’s development policy has been marked by large cuts in the ODA budget, causing ‘real pain’ (according to the World Bank’s number 2) and resulting in one-third of what is counted by the UK as ODA being spent within the UK, not in developing countries.

The aftermath of Brexit and the withdrawal from EU development policy, along with the Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO) ‘merger’ (actually a takeover) of DFID in 2020 (apparently without any planning ahead of time), have, according to the Independent Commission on Aid Impact (ICAI), led to a dominant foreign policy culture, and a loss of DFID expertise, a decline in transparency, less focus on evidence, a reduced culture of internal challenge, and the risk of a large-scale loss of institutional memory.

In short, that is the legacy that a new government would inherit. Maybe the White Paper tries to tidy it up a bit, but it’s a lot to turn around. The White Paper does re-establish poverty reduction as a key aim though the White Paper is not as ambitious overall as it might have been.

The billion-dollar question: Will there be a DFID 2.0?

So, is DFID coming back? The short answer it seems is probably not, at least not in the sense of a new ministry. The shadow Labour team is conducting an internal review before the election. The big strategic questions will be: will the new government focus attention closely on poverty and poverty in the poorest countries or something else? Is there to be a strong emphasis on ODA or ODA-plus’ (i.e. policies as well as spending)? And how will climate change be integrated?

There are four options at least, each with different degrees of upheaval versus gains:

First, the ‘DFID 2.0’ model: A new ministry would involve significant cost and upheaval for an incoming and inexperienced government and could attract much public and media attention to spending overseas amid likely austerity at home. Global trends are also heading in a different direction given the context of the geopolitical turn in development policies. It is though more likely with a coalition government as there is clear support for a new ministry from the Liberal Democrats.

Second, the ‘FCDO-does-development’ model: This would maintain the FCDO and incorporate a stronger development angle within it, such as coherence and cross-government ownership. The White Paper seemed to be heading in this direction. In short, this is the easiest option politically, but it wouldn’t change much.

Third, the ‘DFID-within’ model: This is a step further and would establish an independent development agency with policy and implementation but within the FCDO. So, some freedom but not too much from foreign policy. And at least a voice in cabinet albeit through the Foreign Secretary.

Fourth, a USAID Model: This would create a new development agency outside FCDO, but policy would stay with the FDCO, and implementation would be with the new agency. Again, some freedom but not too much from foreign policy. However, this could relegate development policy politically if there were no cabinet voice.

Which option you see as the best option depends on how important you see a cabinet voice and your appetite for upheaval, but also the level of risk that is implied in drawing attention to ODA at a fiscally constrained and thus politically sensitive moment (which might undermine public support for ODA in the longer term).

Will there be a return to 0.7 percent in UK aid spending?

The short answer seems to be a resounding ‘no’, at least not for a (long) while. There is again an internal review planned by the Shadow Labour team, which will set out the ‘economic tests’ for return to 0.7 percent of gross national income.

Slow economic growth also means the absolute value of UK ODA won’t rise much either. That said, the current £13 bn/year is 0.5 percent reduced from the legal requirement of 0.7 as a ‘temporary measure’. That said, it is still high relative to others. It is above the OECD DAC average and EU average.

The thorny issue will be what is included in that amount. What is counted by donors as ODA is an issue for all donors. Currently approaching £4bn of refugee housing costs within the UK is included as UK ODA or about 30 percent of all UK ODA. This is mainly for Ukrainian refugees (incidentally, Ukraine is also now the second largest recipient of bilateral UK aid, just behind Afghanistan’s).

One question is whether a new government would ever go below the 0.5 which is set as a minimum by the current government. There hasn’t been a public commitment by Labour to stay at 0.5 that I have seen though maybe it is implicit. It seems unlikely as changes would need a parliamentary vote at least, possibly repeal of the 0.7 legislation.

Here's the rub: does a new government continue to allow overseas aid to meet the cost of hosting refugees in the UK? If this is not counted UK ODA falls to 0.36 percent of GNI (£9b/year). Or does a new government continue to count it, despite criticising such accounting, in order that UK ODA remains (but not really) at 0.5 percent of GNI? And it matters a lot as the extra cost of really going back to 0.7 is doubled if the refugee housing cost were to be replaced with new spending. In fact, an extra £8.5bn a year is needed and the chances of £8.5bn/year extra for ODA really seems light years away.

As money is tight there are significant implications for policy. Whether that means a focus on the poorest countries (the politically easy answer, though aid absorption is an issue for aid effectiveness) or more attention to policy coherence (the much tougher thing to do) where ODA will and won’t matter isn’t clear.

What are the signals so far on what a new government might do in terms of policy focus?

If one looks at the keywords in pamphlets, and conference and other speeches from senior Labour figures in the FDCO-related shadow posts, the keywords used seem to resonate well with UK NGO briefings and views, though the detail under the keywords is often limited. Take for a representative example:

The UK will…

- be a development superpower/convenor.

- focus on respect not charity.

- pursue locally led development.

- ensure cross-government thinking.

- integrate development and climate.

- focus on women and girls.

All great in principle, but what the modalities or actions will be to make these concrete is not yet clear. There are certainly ideas emerging from the think tanks. And there are some old faces and behind-the-scenes folks from the 2000s likely to be returning to UK politics from the Blair/Brown years. Many special advisors from the 2000s may well be MPs after the next election.

Other flagship policies include: the five ‘missions’ for UK (do they apply to development cooperation?), a new GB Energy Company (would it have investments in the Global South?), the Green Prosperity Plan and a planned Supply Chain Commission.

In conclusion, what can we see in the crystal ball?

First, the prospect of a DFID 2.0 as a new ministry seems unlikely. A second best is the ‘DFID-within’ which is probably best of the alternatives given the political importance of retaining of a cabinet voice of some kind.

Second, the immediate return to the 0.7 percent commitment won’t happen for some considerable time, and so the future of UK development hinges on presumably maintaining at 0.5 percent of GNI (a public commitment on that would be good) and spending differently, and ideally not including in ODA counting things that aren’t really ODA. The fiscal constraints could also mean UK policy has a greater emphasis on only very poor countries or policy measures beyond ODA spending.

Third, while Labour’s oft-repeated keywords and phrases align well with statements from UK NGOs, their level of generality raises questions about what would really change compared to the conservative government. And there is too little attention at least in public on the immediate crisis of debt servicing, which will get worse and likely be acute over 2025/2026.

Finally, there’s the wild card. If the UK election is in mid/late November, it’s possible the new government would establish itself in a world where Donald Trump has won re-election to the White House and his threats to leave international institutions may become real. That would make the UK’s international and development cooperation policies as important as ever. With the world looking for global leadership outside the US, a new UK government and like-minded other governments will need to decide if they want to become the keepers of the multilateral flame.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.

Image credit for social media/web: Horváth Botond / Adobe Stock