Recommended

By the end of primary school, students in Bangladesh are expected to have acquired foundational skills such as basic reading, writing, and numeracy. However, recent assessments conducted by various government institutes reveal that the proportion of Bangladeshi students not meeting grade-level reading comprehension and mathematics standards is extremely low – more than half of children in grades 3 and older lacked required competence in maths and Bangla in 2022.

Even before the pandemic, children in Bangladesh performed poorly on both foundational and grade-level assessments of competency. There is a dearth of representative data that effectively compares pre- and post-pandemic learning outcomes for these children, which makes it difficult to identify the extent of learning loss that can be attributed to pandemic-related school closures. We conducted a two-phase study that aims to plug this gap—collecting data on students' learning levels across 61 districts in Bangladesh (excluding CHT districts) to track their progress between January and July 2023 (details on sample and test can be accessed here). This blog provides an overview of the findings from both phases and their implications for policymakers.

Children are typically more proficient in Bangla than in English and Maths.

For this study, we used the ASER tool, which tests students on competencies in Bangla (till Grade 1), English, and Maths (till Grade 3). To observe differences in the learning outcomes of children across two rounds, we classified their test performance into four distinct categories:

-

Children who initially performed at or above grade level in Round 1 but performed below grade level in Round 2 are classified as having declined in terms of their learning levels.

-

Similarly, children who demonstrated below-grade-level proficiency in Round 1 but grade-level proficiency or higher in Round 2 were categorized as improved.

-

In cases where a child's proficiency level remains unchanged between both periods, we divide them into two categories:

-

those whose performance remains below grade level in both rounds ("Remains below grade-level") and

-

those whose performance remains at or above grade level ("Remains at/above grade-level").

-

In our sample, most children (62 percent) have basic literacy skills in Bangla. Children demonstrated the lowest proficiency in English across both rounds; in Round 2, 64 percent of them continued to lack expected literacy skills. More than half of the children in our sample exhibit gaps in foundational numeracy skills---specifically, 33 percent of the children fail to develop these skills over the two rounds, and 18 percent fail to retain them in Round 2. Although timely identification of these gaps is critical for potential remedial measures, a three-month observation period might be insufficient to detect any considerable progress, particularly in subjects where children don’t excel.

Figure 1: Changes in foundational literacy and numeracy levels between survey rounds 1 and 2

Note: Overall: N: 2417. Gender, region, food insecurity, and poverty are associated with lower performance in foundational tests.

Round 1 findings indicated that girls outperformed boys on assessments of foundational skills, especially in Bangla. However, in Round 2, fewer girls than boys showed improvement, with girls showing the least progress in English and Maths. We find that rural, economically disadvantaged (as measured by the Poverty Probability Index (PPI)) and food-insecure children are more likely than their peers to demonstrate below-grade-level literacy and numeracy skills (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Changes in foundational literacy and numeracy by gender, rural/urban, poverty likelihood, and food security

Panel A (left): Changes in foundational literacy and numeracy levels (R1 and R2), disaggregated by gender.

Overall N: 2,417. Males: 1,146, Females: 1,271

Panel B (right): Changes in foundational literacy and numeracy levels (R1 and R2), disaggregated by strata.

Overall: N Rural: 1,268; N Urban: 1,149

Panel A (left): Changes in foundational literacy and numeracy levels (R1 and R2), disaggregated by poverty likelihood.

Panel B (right): Changes in foundational literacy and numeracy levels (R1 and R2), disaggregated by household's state of food security.

Panel A note: Children from households that are less likely to be poor- Above the median: 1,238; Children from households that are more likely to be poor- Below the median: 1,171, Overall children: 2,409. Since not all households responded to the household module, the sample of children with poverty likelihoods varies from the overall sample.

Panel B note: Note: Children from households that are food secure: 1,655; Children from households that are food insecure: 753, Overall: 2,408

Rural children exhibit lower performance levels than their urban peers across all three literacy and numeracy assessments. Similar trends can be observed in the case of children coming from economically disadvantaged and food insecure households; a greater proportion of these children demonstrate foundational skills below the grade level in comparison to their peers. A plausible explanation could be that children from privileged families are more likely to have access to a diverse array of learning resources and mentors, both of which can assist them in bridging these foundational gaps.

A substantial portion of students in classes 4 and above have below-grade-level English literacy and numeracy skills

We also administered the ASER to students in higher grades to assess the foundational capacities of children in higher grades.

Figure 3: Grade-level competency trends, as measured by ASER

Panel A (left): Share of students who have below grade-level English proficiency (R1 and R2), disaggregated by grade.

Panel B (right): Share of students who have below grade-level numeracy (R1 and R2), disaggregated by grade.

Panel A note: Grade 1: 121, Grade 2: 188, Grade 3: 270, Grade 4: 231, Grade 5: 286, Grade 6: 241, Grade 7: 217, Grade 8: 214, This graph displays both currently enrolled grade levels and the last grade a student attended before dropping out. Data on their last grade level was obtained from the Back-to-school survey.

Panel B note: Grade 1: 121, Grade 2: 188, Grade 3: 270, Grade 4: 231, Grade 5: 286, Grade 6: 241, Grade 7: 217, Grade 8: 214, This graph displays both currently enrolled grade levels and the last grade a student attended before dropping out. Data on their last grade level was obtained from the Back-to-school survey.

The gaps in English literacy do not appear to diminish as children advance grade levels, with the majority of upper primary and junior secondary students performing below grade-level expectations (see Figure 3). It appears that students' foundational numeracy skills increase as they advance through grade levels, but not at the expected rate, given that children still failed to solve simple subtraction and division problems.

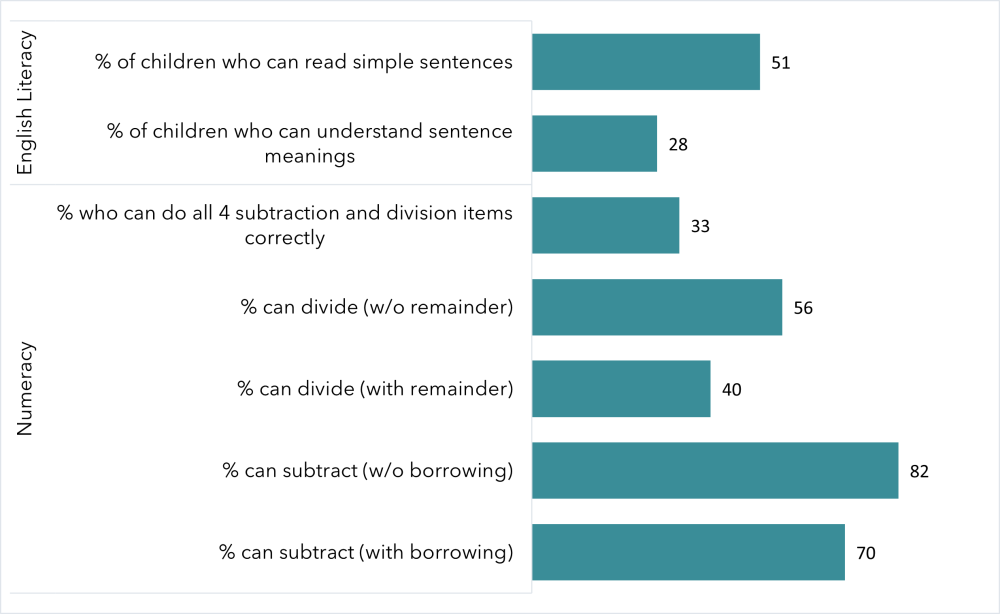

Observing the performance of children on selected English and numeracy test items reveals that less than half of older children (between grades 6 and 12) can read simple sentences, with even fewer being able to correctly interpret their meanings (see Figure 4). Only one-third of older children in grades 6 and above could solve all four elementary maths problems correctly. We also see that fewer older children can correctly solve division and subtraction problems requiring carryover and remainders.

Figure 4: Children’s performance on selected English and maths test items (only for children in grades 6-12)

Note: N of students in grades 6-12: 1322. Note: The percentages depicted for English literacy are for the overall sample i.e. the sample is not restricted to only children who were given sentence-related tasks.

What can we learn from this?

The findings obtained from this study do not present a novel issue: students performed poorly in Maths and English even prior to the pandemic, and post-pandemic assessments have only served to underscore this. Nevertheless, foundational gaps do not necessarily indicate a lack of learning. Instead, they signal that these gaps in understanding, which may have developed in earlier grades, can persist given that sixth graders cannot perform subtraction or division operations at the third-grade level. Differences between groups still exist even at young ages. Recent evidence, however, indicates that merely narrowing the learning divide between the rich and the poor is insufficient to ensure universal literacy and numeracy in low-performing nations.

Monitoring children's learning outcomes permits early identification of existing learning gaps and makes it possible for education policymakers to take the necessary steps to prevent their deepening. The recurring existence of foundational-level learning gaps in children, as evidenced by a series of assessments conducted over time, should prompt policymakers to consider the incorporation of Teaching at the Right Level (TARL) strategies into existing pedagogical approaches. Further research is needed to determine whether this approach would be effective for Bangladeshi children, but it’s high time that we get started.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.

Image credit for social media/web: Popi / Adobe Stock