The COVID-19 pandemic presents decision makers worldwide with unenviable policy choices. In many high-income countries, so-called non-pharmaceutical interventions—including lockdown and social distancing measures—have been implemented to buy time so that hospital intensive care unit (ICU) capacity can be rapidly built up to meet the anticipated rise in numbers of very sick patients. There will be major challenges in implementing equivalent measures in low-resource settings (LRS), where the sustainability of society-wide lockdown is questionable and intensive care bed capacity is generally limited to a few specialised centres in each country. This blog focuses on hospital treatment for COVID-19 patients in LRS, considering what we know about the spectrum of COVID-19 illness and what this tells us about where resources might best be focused in LRS. As elsewhere, decision makers, global and local, must prioritise resourcing and capacity development for the ward-level care and simple oxygen therapy that most hospitalised COVID-19 patients will need—not the high-end clinical care that may well be impossible to scale-up in time in countries with limited resources.

Prioritising resources is especially relevant as countries look to mobilise domestic and external support for the COVID-19 response within the important healthcare constraints present in LRS. The World Bank Group is expected to deploy an unprecedented $160 billion over the next 15 months, whilst the Global Fund has agreed to repurpose 5 percent of new allocations, as well as grant savings and underutilised assets, toward COVID-19 for the time being. It is important that these resources are spent wisely to maximise lives saved and minimise disruption to health services for non-COVID patients.

What do we know about the spectrum of illness and healthcare needs in people who contract COVID-19?

Data from countries at the leading edge of the pandemic (China, France, Italy, Spain, the UK, and the US) paint a grim picture of what’s to come for developing countries. The data tell us that (1) the pace of spread is accelerating and many low-income countries will unavoidably face rapid rises COVID-19 caseloads in the coming weeks and months as community transmission takes hold, but also that (2) clinical need for inpatient care is still limited to a fairly small number of infected patients.

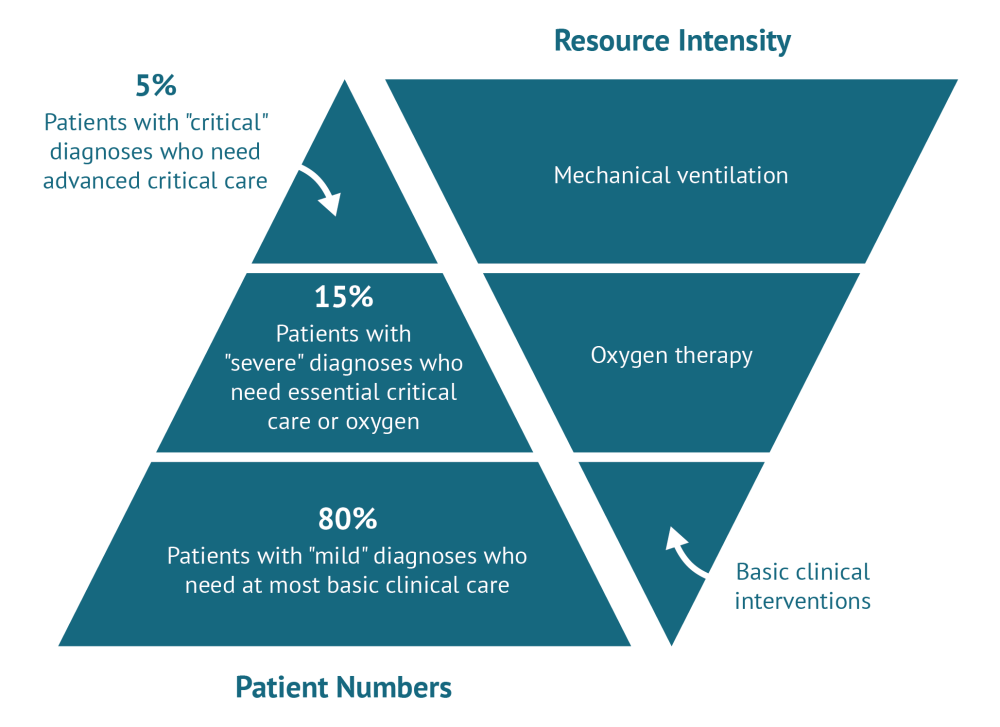

The figure below summarises the spectrum of clinical support available for COVID-19 patients in LRS. Among COVID-19 patients who are identified (the majority of those infected develop no or mild symptoms), about 80 percent experience mild illness up to and including mild pneumonia that can mostly be managed in the community. The remaining 20 percent includes a minority (5 percent of those who exhibit symptoms overall) who are the most critically unwell, typically because of severe breathing difficulties and/or underlying conditions such as heart failure or poorly controlled diabetes that COVID-19 appears to exacerbate. This 5 percent of the symptomatic patients have been treated with invasive mechanical ventilation in ICUs in high-resource settings.

Breakdown of patients with identified COVID-19 (left) and the spectrum of clinical intervention options focusing on breathing support (right).

Why models of care from high-income settings are likely to be inappropriate where resources are scarce

There are good reasons to question whether it is appropriate and feasible to scale up ICU capacity in low-resource settings to meet the demands outlined above:

-

On clinical effectiveness, we know that clinical outcomes for patients treated in ICUs in HIC settings in the pandemic so far have been poor, partly reflecting that this is where the sickest patients go. A study published in 2019 found that anywhere between 36 and 72 percent of patients on ventilators also die in low- and middle-income countries. Furthermore, mechanical ventilation is complex to administer and many COVID patients who receive it will require additional intensive clinical intervention during or after ventilation. Finally, we know that blanket adoption of practices used in high-income settings can be detrimental to clinical outcomes in LRS where the ability to discriminate clinically between conditions that have very different management approaches is more difficult, and where health workers trained to deliver ICU care safely simply are not available in the numbers needed.

-

On feasibility of implementation, an ICU-focused care model will be practically and economically impossible to implement in LRS on the timeline needed to support the COVID response, even with the “delaying of the curve” brought about through social distancing and shutdowns. Although ICU capacity metrics are unreliable and there are big variations in baseline capacity across countries, we know that availability is restricted to a handful of major care centres often located in urban areas. Reliable electricity, oxygen supply, ECG and vital sign monitoring, advanced supporting equipment and medications, ideally negative pressure rooms and high-specification protective equipment for medical staff are all prerequisites for appropriate use. Many are unattainable in LRS. Crucially, the commodity and human resource needs to manage COVID-19 patients are considerable. Safe delivery of mechanical ventilation in ICU settings depends on a long list of equipment and infrastructure requirements as well as on large numbers of specialised staff (often three or four full-time equivalents per bed). Although novel programmes for capacity development in intensive care are emerging in LRS, safe care depends on availability and/or upskilling of trained human resources for health, which cannot be met on the timescales required to respond to COVID-19.

What options may be open to decision makers in low resource settings—and how can the global health community help?

If a majority of hospitalised COVID patients can be safely managed on general wards, what models can we look to? Critical care is a specialism in its infancy in many LRS, but there is a growing body of evidence on essential interventions that can be applied to help manage the anticipated influx of COVID-19 cases. This evidence points to some key actions for decision makers and service managers in LICs to consider. Given the rapidly accelerated spread of COVID-19, the priority is to identify interventions that can be implemented at pace and maximise lives saved.

-

Prioritise simple hospital interventions to save the most lives. Decision makers at the country and the global levels should prioritise investments that deliver the most value at the lowest cost in LRS. Despite general uncertainty about alternative options, we do know that some interventions, contingent on available human and physical resources, could make a real difference. These include:

-

Emphasising essential emergency and critical care where appropriate for those patients in LRS who do become critically unwell. Basic interventions such as delivering oxygen to patients lying on their front (“proning”), suction, chest physiotherapy, and appropriate use of antibiotics for bacterial infections will help improve outcomes.

-

Providing personal protective equipment (PPE) to protect frontline staff and prevent infections acquired in hospital. Decision makers should prioritise testing and PPE for frontline staff in tandem with better management of existing facilities and equipment to ensure adequate spaces for delivery of essential care and to reduce the risk of infections spreading in hospitals. Protecting both patients and the healthcare workers looking after them is essential in LRS where healthcare professionals and hospitals are in short supply.

-

Using locally appropriate tools to guide effective care. Effective triage procedures will be key to identifying how best to stratify care for suspected COVID patients. Indicative evidence from countries such as Uganda using clinical criteria at presentation shows that triage tools can be developed and evaluated at pace. Guidelines will also be needed to govern how and when clinical interventions that seem to be showing promise elsewhere are used to best effect in LRS. And whilst guidance on best care for COVID-19 in LRS is still emergent, there is indicative evidence that decision makers can draw on.

-

Shifting some tasks related to the care of COVID patients to less specialized health workers. These protocols can also drive task shifting, which has been shown to be an effective strategy for broadening access to HIV care in LRS but for which evaluation in emergency care settings is limited. Task shifting will not be a panacea however; it will support provision of essential emergency and critical care but cannot be a replacement for qualified specialists in delivering advanced care, such as mechanical ventilation.

-

-

Align global-development-partner-supported commodity procurement with country realities to enable delivery of the highest value interventions. Purchasing decisions for critical care equipment should be context sensitive and made in consultation with frontline clinicians, emergency care specialists, anaesthesiologists, and intensive care specialists working in countries. HIC-driven models of epidemic progression matched against stated capacity to identify shortages (e.g., here and here) are useful inputs in the decision-making process but we must remember that scaling up (or setting up) ICUs in LRS have few if any parallels with models forecasting demand for malaria, HIV, or tuberculosis commodities. Knowledge on human resources for health, auxiliary equipment, existing (and upgradeable) infrastructure, all matter critically. Procurement would do well to focus on oxygen supplies, suction, and vital delivery and monitoring systems, such as pulse oximetry, as well as the provision of PPE for healthcare workers, which can be deployed and save lives.

-

Carry out pragmatic research to understand what works in LRS in support of a learning healthcare system. There is an urgent need to understand clearly the likely burden of infection requiring hospital care and to develop locally appropriate triage and clinical care guidance based on ground-level data on what works (and what doesn’t) in LRS. Decision makers should prioritise support for rapid and pragmatic research to help guide prioritisation and spending decisions on a continuous basis to support a learning healthcare system.

The COVID-19 pandemic demands rapid system resilience strengthening measures in LRS to help health providers cope with anticipated increases in demand. This is not going to be health system strengthening in the usual sense of the term, nor can it be achieved through high tech fixes—time is very short, and it is unlikely that human and infrastructure resources can be mobilised or indeed created at scale quickly enough to ramp up intensive care to clinically effective levels given the complex care requirements involved. Instead, decision makers should focus on scaling-up resourcing and capacity development for ward-level care for the much larger proportion of patients that are likely to need it.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.