Recommended

Food insecurity is again a major topic of global concern. Decades of progress are under threat from the effects of climate change on agriculture along with supply chain dislocations linked to the pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. An estimated 333 million people worldwide are now experiencing acute food insecurity—more than double 2019 levels.

The Biden administration has put significant emphasis on addressing these challenges, but much of its focus is on crisis relief. The US has channeled considerable humanitarian support through the World Food Program, outpacing other donor contributions. But the current situation also calls for significant longer-term development investments to help countries adopt agriculture systems that are more able to withstand climate change and less vulnerable to international supply shocks. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen outlined as much in her remarks at a Global Food Security side event at this year’s UN General Assembly, where she called on countries to “collectively do more than respond in moments of crisis. We must build resilience to them.” Yellen’s call for resilience has been echoed by other policymakers in the international community, and COP28, which kicked off on Thursday, is set to spotlight food systems as a key theme. Officials should look to the organizations that are making the greatest impact on this front and help scale up their financial firepower. In this context, the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) stands out as a particularly important vehicle for advancing a sustainable global food security agenda.

What is IFAD?

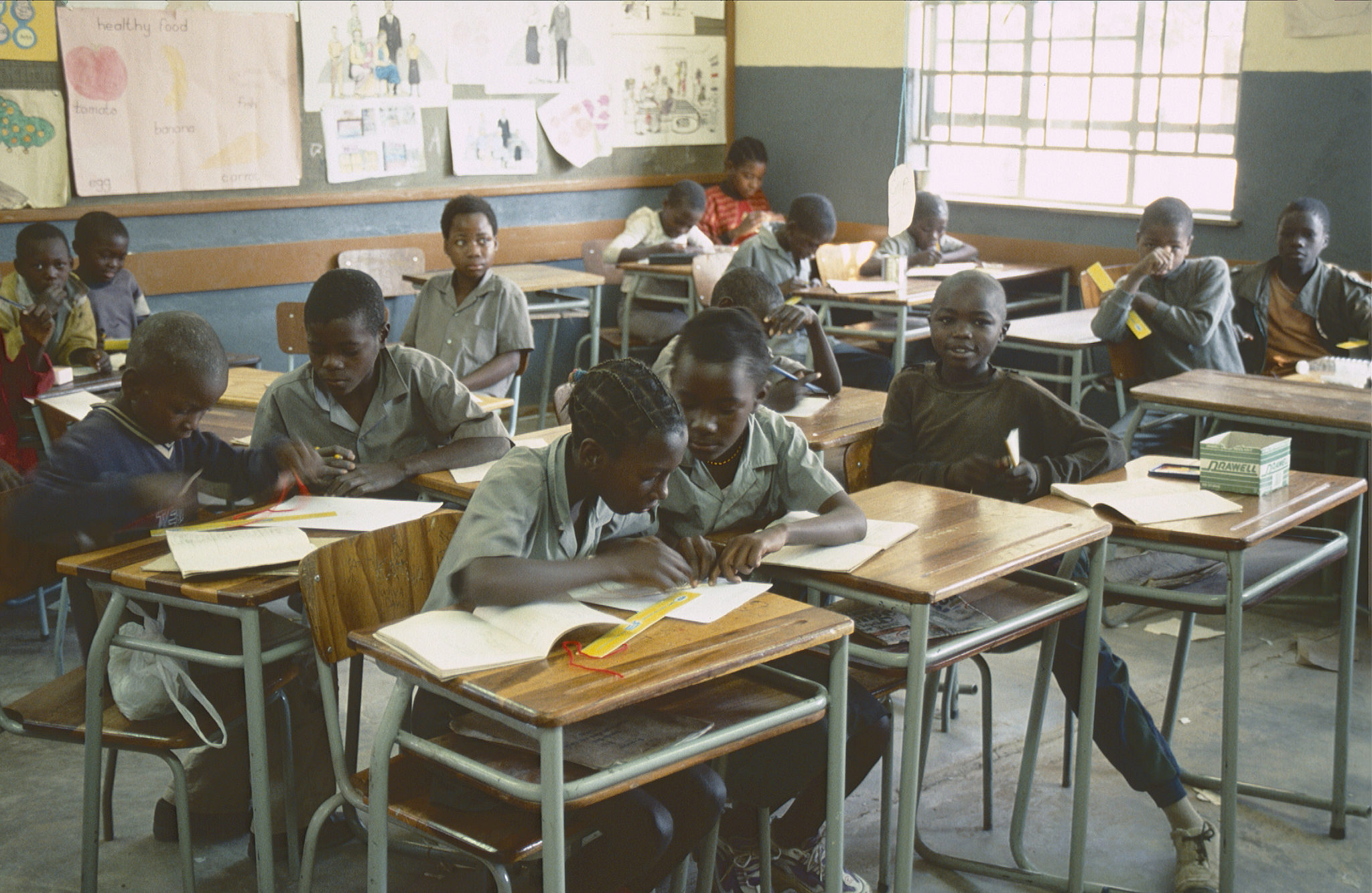

Born out of the global food crises of the early 1970s, IFAD was established in 1977 as an international financial institution to finance agriculture projects in rural areas of the world’s poorest countries. Sitting alongside the other two Rome-based UN food agencies—the World Food Program and the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO)—IFAD is unique in that it functions more like a development finance institution. It finances projects that are country-owned, meaning the projects it invests in are embedded in the government’s national strategy and run through government systems. Other organizations invest in agriculture, but IFAD works exclusively with small-scale farmers, who are responsible for roughly one-third of the world’s food production and requires that its programs focus on the poorest regions in the countries where it operates.

Much like an MDB concessional window, IFAD provides concessional loans and grants—i.e., funds much cheaper than the country could get from the private sector—to governments. As a result, IFAD’s coffer must be replenished every three years to maintain lending capacity. This year IFAD launched IFAD13, its 13th replenishment, and donor governments will come together in Paris in the coming weeks to pledge new funding that will determine IFAD’s financing capacity for the next three years.

IFAD’s most recent past replenishment, IFAD12, marked the first time since 2009 that the institution was able to significantly bolster its financial capacity. The 2009 bump came at a time that many poor countries were grappling with skyrocketing food prices against the backdrop of the global financial crisis, and donors—led by the US—stepped up their contributions in response.

The case for IFAD

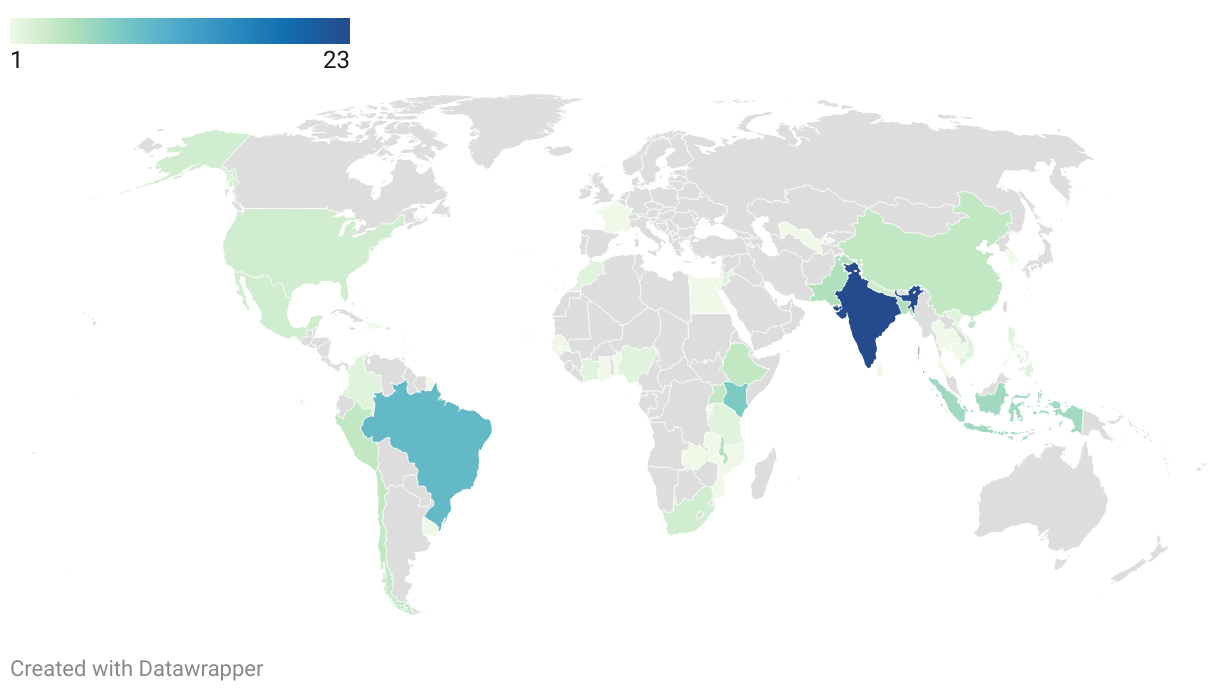

As the IFAD13 pledging session approaches, donors should give serious consideration to another increase. The case is strong: by focusing on smallholder farmers and helping them adopt more sustainable practices in the face of climate change, IFAD is addressing some of the defining development challenges of our time. And as global supply chains become more complex, and often unreliable, IFAD is helping to bolster local and regional agricultural systems, making countries less prone to external supply shocks. But it’s also pretty good bang for buck: last year, as part of its IFAD12 pledge, the United States provided $43 million for IFAD—and the institution disbursed more than $880 million. Finally, a CGD-designed tool for comparing development agency effectiveness across multiple indicators ranked IFAD 1st overall among 49 aid providers. In a world awash in multiple food security institutions, but where grants are scarce, donors should focus on bolstering organizations that are delivering.

Current state of play

Early indications point to donor ambition for IFAD13. Several member countries—France, the Netherlands, Norway, and Spain—have already announced significant increases to their contributions, with French President Emmanuel Macron notably announcing a record $150 million pledge to IFAD in September (a 60 percent increase from the country’s IFAD12 contribution), which the Netherlands matched with its own $150 million pledge at COP (an 80 percent increase from the country’s IFAD12 contribution) and a handful of developing countries, often on the receiving end of loans from IFAD, stepped up their support for the Fund with early pledges.

US role

The US has historically been the largest contributor to IFAD and has considerably shaped the institution’s policy direction. Over the years, IFAD has enjoyed strong bipartisan support from Capitol Hill: Lawmakers even stepped in to support the institution when the last administration walked away from the pledging table. But while holding the mantle as the largest donor, US contributions to IFAD have remained relatively modest at a projected $129 million over the three-year cycle. The administration has already signaled a strong interest in seeing IFAD do more. The president’s FY24 budget request, which covers the last year of the IFAD12 replenishment cycle, included an ask for additional money for the IFAD’s ASAP+ program (focused on climate adaptation) and to pay down past unmet commitments.

A bipartisan coalition of senators hopes to bolster global food systems by establishing a new institution designed to mobilize private sector investment in target countries. We appreciate the drive but hope lawmakers won’t sleep on the opportunity to get more out of a high-performing institution already in the game. IFAD13 is a perfect vehicle for that ambition.

Thanks to Erin Collinson for helpful comments.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.

Image credit for social media/web: sulit.photos / Adobe Stock