Acknowledgement: This policy note was originally prepared at the request of the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH (Sector Project Global Public Goods and Multilateral Development Banks) in support of their advisory work for the German government. The note benefits from substantial dialogue with staff at GIZ and BMZ, as well as a German government roundtable in Berlin in January 2020. The note is reprinted as a CGD note with the permission of GIZ and BMZ. All opinions are the author’s alone.

Introduction

The World Bank’s non-concessional borrowing (NCBP) policy for IDA countries was introduced in 2006 following major rounds of debt relief and debt cancellation for a large subset of these countries through the Heavily Indebted Poor Country Initiative and the Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative. The aim of the NCBP was to preserve the gains for the debt relief recipients as part of a broader strategy of assistance focused on better debt monitoring and management of external borrowing.[1]

The World Bank now moves toward implementation of the successor to the NCBP in the form of a Sustainable Development Financing Policy (SDFP) in a much different context from 2006. At the time, global economic conditions were favorable, and the fiscal space and access to external credit (along with, arguably, the policy reforms implemented as part of debt relief conditionality) all served to spur significant and sustained economic gains for these countries. Importantly, the NCBP itself, which intended to restrict IDA country access to financing on non-concessional terms under certain circumstances, was rolled out amidst these favorable conditions for IDA countries and the global economy. That is, the policy was aimed at managing a generally favorable situation: increased access to a broader range of financing options for lower income countries.

This situation stands in dramatic contrast to the current picture. Uncertainties around the global outlook due to the COVID-19 pandemic are amplified in low income countries. The World Bank is projecting the first recession for Sub-Saharan Africa in 25 years; private finance will likely pull back from developing country markets in the months ahead; and the behavior of bilateral official creditors from countries that are now on the front lines of the pandemic is highly uncertain. Multilateral creditors will almost certainly scale up crisis financing, but the overall picture for external financing for developing countries is very troubling.

In this crisis environment, the first order concern for policymakers may not be too much access to non-concessional finance. Hence, the NCBP and new SDFP might seem largely irrelevant during this crisis period. But it is important to recognize the salient features of the basic architecture of the new SDFP: enhanced engagement with IDA countries to improve debt management (Pillar 1), and better coordination among official creditors to help IDA countries manage debt risks (Pillar 2).[2] While the new policy itself may not be the main driver of these activities during the crisis, its long-term success will depend on the ability of the World Bank to manage both sets of activities as well as possible in the months ahead.

The salience of the SDFP’s key features is reflected in the recent G20 agreement on a bilateral debt standstill for IDA countries. The announcement itself reflects a step forward on coordination among Paris Club and non-Paris Club creditors, and one of the terms of the agreement is adherence to the NCBP, which presumably carries overto the SDFP as adopted by the World Bank board.[3]

Overview of debt landscape and risks

If we are in fact entering a widescale debt crisis across developing countries, one that engulfs low income countries as well, it is important to recognize the degree to which non-concessional borrowing by these countries has been an exacerbating factor. Prior to the current crisis, the share of low-income countries in debt distress or at high risk of distress had grown significantly, from 23% in 2013 to 51% by the end of last year (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Debt risk ratings for low-income coutnries

Source: World Bank LIC DSA Database, 2019.

Rising debt risks have coincided with a shift in the composition of external creditors to these countries.[4] Just prior to the global financial crisis, multilateral institutions accounted for a clear majority of lending flows to low income countries. Ten years later, multilateral creditors account for less than one-third, with commercial and bilateral creditors accounting for about two-thirds. Among bilateral creditors, traditional government lenders (the “Paris Club” of creditors) have been eclipsed by non-traditional lenders. And among these non-Paris Club creditors, China is the dominant actor, though a lack of lending transparency makes precise estimates difficult. World Bank estimates of debt stocks suggest that the Chinese government accounts for about 75% of the growth in non-Paris club lending over the past decade.

The effect of this shift in creditor composition on debt risks is clear. Commercial creditors do not offer concessionality in their lending, pricing according to country risk. Bilateral creditors in turn offer very little concessionality, in comparison to multilateral lenders (see Table 1). Since 2007, multilateral lenders like the World Bank have offered mostly concessional terms to their low-income borrowers, while bilateral creditors have offered mostly non-concessional terms. As a result, the shift away from multilateral borrowing by low income country governments has meant a hardening in terms facing low income countries.

Table 1. Concessional lending as a percent of total lending

| Concessional Lending as Percent of Total Lending, Average of 2007-2018 | Concessional Lending as Percent of Total Lending, Average of 2016-2018 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Debt Stocks | Bilateral | 28% | 27% |

| Multilateral | 81% | 80% | |

| Debt Service | Bilateral | 18% | 14% |

| Multilateral | 55% | 58% |

Source: World Bank International Debt Statistics (IDS). Concessional debt is defined as loans with an original grant element of 35 percent or more.

With harder terms have come higher debt service costs, which have been a key driver of debt risks in recent years. Although multilateral creditors continue to account for the largest share of debt stock for low income countries, they have been a declining share of debt service costs due to non-concessional terms from other creditors (see Figure 2).

With rising debt risks among IDA countries prior to the current crisis, these countries are in a particularly vulnerable position as they confront the massive economic shocks associated with the pandemic. It would be unreasonable to expect adequate planning for this once-in-a-century event. But it is also clear that the World Bank’s NCBP had already failed to help guard against debt risks in these countries even prior to this crisis. It is important, then, to assess how well the new policy is likely to perform amidst the crisis and beyond.

Figure 2. IDA debt service by creditor type 2007-2022 (USD Billion)

Source: World Bank IDS.

Assessment of NCBP performance

As with the NCBP, the primary objective of the SDFP appears to be to affect the behavior of IDA countries and their creditors when it comes to non-concessional borrowing decisions and thereby avoid debt distress situations for these countries. From this basic standpoint, the evidence on performance of the NCBP is discouraging. It seems clear in practice that the NCBP has sought to be the “tail wagging the dog” when it comes to affecting borrowing country behavior. IDA’s resources have proved to be too small relative to those of other creditors to significantly affect borrower behavior through the NCBP’s disciplinary tools. And the creditors themselves have not proved to be sufficiently attentive to the goals of the NCBP to adjust their lending practices accordingly.

The changes under the new SDFP do not appear to fundamentally change the weaknesses of the existing policy in this regard, pointing to significant risk that the new policy will not have a measurable effect on borrowing and lending decisions across IDA countries. The SDFP primarily entails a broadening of country coverage, the inclusion of domestic debt as well as more attentiveness to other features of non-concessional borrowing (e.g., collateralization and contingent liabilities), a shift to a “set aside” model to incentivize Performance and Policy Actions (PPAs), and a commitment to more World Bank-led coordination among IDA country creditors.[5]

Each of these elements is well considered and has merit, but they all bear the same risks of failure as has the existing NCBP policy: that the World Bank and its financing simply isn’t powerful enough to affect significant change among borrowing countries and their full array of creditors. It is important to have a clear view of the evidence on NCBP performance to properly assess these risks.

The evidence presented by the World Bank suggests that countries covered under the NCBP and their creditors showed little responsiveness to the policy or even awareness of it.[6] In the most recent assessment of DeMPA scores among 65 countries, the World Bank reports that a simple majority of countries met minimum scores in just 3 of the 14 benchmarks (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. DeMPA minimum scores by percentage of countries

Source: World Bank DeMPA results, end-2018. Percentage of low income countries accessing market-based financing. 65 countries surveyed.

Of course, these are broad measure of country debt management performance and can not be attributed directly to the NCBP itself. But these performance assessments point the low level of capacity overall in borrowing countries, and more direct measures of NCBP performance suggest modest effects on the overall picture. For example, a bank comparison of countries subject to NCBP with other IDA countries concludes that the NCBP countries did not perform better on debt sustainability than their comparators.[7] Further, the World Bank’s annual capacity assessment under the NCBP has identified a deterioration in performance as overall debt risk have increased: between 2018 and 2019, the number of countries identified as weak when it comes to the quality of debt monitoring grew from 32 to 38, representing more than half of the assessed countries.[8]

To some degree, declining performance could reflect the growing complexity of the tasks. The new policy identifies the more complex features of non-concessional debt today, and the more varied behavior of IDA country creditors, with greater reliance on collateral requirements, as well as public-private partnerships that entail contingent liabilities for the government. The emergence of these lending practices increases the burden on IDA country governments to perform basic tasks around debt reporting and management.

When it comes to the behavior of other creditors in relation to the NCBP, the World Bank assesses its NCBP engagements with non-MDB and non-Paris Club creditors as “sporadic” even though these have been the fastest-growing groups of creditors and now outpace MDBs in overall lending. Perhaps even more damning, the bank’s survey of 18 peer MDBs regarding the NCBP delivered only 10 responses. The bank reports that “more than half” were familiar with the NCBP and factored it into their lending decisions. That suggests that nearly half the MDB respondents were unaware and/or did not factor the NCBP into their decision making, with eight MDBs remaining unaccounted for.[9] Given the basic similarities and common governance arrangements across the MDBs, the paucity of evidence of meaningful coordination on NCBP issues is particularly discouraging.

In sum, assessments of the NCBP and country performance under the NCBP point the acute challenges facing the World Bank’s efforts to support debt sustainability in its client countries. This sober assessment is an important starting point for considering implementation of the new SDFP.

Risks and opportunities for SDFP: Assessing accountability for key actors

The SDFP does not adequately justify how or why an expansion of coverage to all IDA countries, the coverage of domestic debt, or the commitment to more creditor outreach efforts will improve this picture. The implied aim is that the new set aside model will entail deeper engagement in all IDA countries, which will improve the delivery of country commitments on effective debt management practices. In principle, this may be possible, but the policy will need to be closely monitored as it is operationalized. We can think of SDFP accountability in three categories: IDA countries; the World Bank, and IDA country creditors.

IDA Countries

The core conditionality of the SDFP’s first pillar poses a dilemma during the crisis period. As noted earlier, IDA country adherence to the NCBP/SDFP is a condition on the terms for the 2020 G20 debt standstill arrangement. But conditions within the SDFP itself could run counter to crisis response, depending on the depth and length of the crisis period. As the bank seeks to front load IDA assistance to meet IDA country needs during this uncertain period, it is not clear how a set aside arrangement will function over an extended crisis period. It is questionable whether any specific performance criteria are advisable across the full range of debt management issues when there is an overriding imperative for fast disbursing assistance.[10]

The revised SDFP paper addresses this dilemma, indicating a narrower PPA focus on transparency issue and limited debt management issues during the first year.[11]Further, the set asides will not be employed until the second year of IDA19, though PPAs during the first year will guide second year decisions.

The G20 agreement also conditions the debt standstill on full debt transparency among IDA borrowers seeking a standstill arrangement. The G20 announcement calls for MDB technical assistance to support this condition. Given this framework, the transparency condition might serve best as the primary, if not sole, basis for SDFP conditionality for 2020 country programs, consistent with the revised policy’s call for a narrow PPA focus.

Beyond the crisis period, a more nuanced and tailored approach to performance targets, in line with the SDFP proposal, makes sense. The SDFP intends to tailor performance targets to the circumstances of each country, which is sound given the variations in country capacities. It also intends for targets to be simple, rather than composite, indicators focused on key vulnerabilities in each country case. Again, this appears sound in providing the right incentives for IDA countries. However, there remains a question of overall rigor: how high a bar will each country face? This is ultimately a subjective question and will require scrutiny by the board on a country by country basis. There are also questions about equitable treatment across countries when it comes to PPAs, which will be the responsibility of bank management, something we address in the next section.

World Bank

Low conditionality for IDA countries during the crisis period does not mean low effort when it comes to areas of debt management capacity that have direct bearing on crisis response. One element of the World Bank’s agenda should be adequate provision of technical assistance on core elements of debt management. This applies to the range of core debt management issues assessed in the earlier section and addressed later in the key recommendations. It should also pertain to ancillary activities associated with the SDFP. For example, there is too frequently inadequate information about projects that IDA countries would like to pursue through non-concessional borrowing, which makes it difficult for country teams to assess around key dimensions like project rates of return.[12]

The integration of the new SDFP into IDA’s results framework is modest. The Tier 2 indicators on Governance include a single relevant measure: “the number of IDA countries publishing annual and timely public debt reports.” As stated, this represents a low bar, with no qualitative assessment implied. For example, how will the bank seek to assess the comprehensiveness of debt coverage (guarantees, SOEs, etc), an issue that it identifies as increasingly important?

More generally, the new policy relies on the bank’s commitment to prioritize debt sustainability issues in country programs through existing systems—namely through better prioritization by country teams. But it is difficult to evaluate how this will appear in practice. It’s not clear that the new policy will have a significant effect on underlying incentives at the country team level, where country relationships and a front line commitment to the pursuit of development projects may outweigh any willingness to take a tougher stance on debt issues. Given the new policy’s emphasis on efforts by country teams (including on creditor outreach issues addressed in the next section), it will be important for Bank management to offer more detail over the course of policy implementation on how the SDFP is being incorporated by these teams, how the teams are incentivized to prioritize SDFP issues, and how the work is being supported by additional resources.

Finally, the SDFP’s tailored, country-by-country approach appropriately recognizes the different circumstances of IDA borrowers—some may have strong transparency standards but are weak in other areas of debt management. That said, a tailored approach runs the risk of inequitable treatment across countries, with more (or less) aggressive approaches that may depend more on the behavior of country teams than the broad objectives of the SDFP. The current policy does not identify a clear framework or set of rules to ensure consistent treatment across countries. Some areas of focus for PPAs may lend themselves to uniform rules across countries. For example, if tax to GDP is below a certain threshold, tax policy and administration would automatically be triggered as an area focus. Clearer articulation of such rules and triggers would be useful going forward.

Creditor Community

In general, proposed Pillar 2 efforts to improve creditor outreach under the SDFP are vague, and the level of ambition suggested by “outreach” (the stated objective of Pillar 2) versus “coordination” or “commitments” is low. The policy identifies a new SDFP website for creditors’ use, and in fact, the IDA country pages do provide a useful presentation of country debt issues and countries’ positions in relation to SDFP. The question is the degree to which the website becomes a meaningful information platform, one that directly informs decision making, for the broader community of creditors. This will depend on a more aggressive stance from the Bank, one that is strategic and seeks to move beyond education and outreach.

The World Bank should have two objectives with regard to other creditors. First, maximizing coordination with like-minded creditors (other MDBs, the IMF, etc.) to strengthen the incentives/disincentives that borrower face. Second, imposing greater discipline on the behavior of other creditors who currently appear to act with indifference to the goals of the NCBP/SDFP.

Both objectives require a more detailed engagement plan that goes well beyond educating these creditors to ensure awareness of World Bank policies. The policy offers a framework for outreach to categories of creditors, but there is a lack of prioritization or realism about what the Bank can credibly achieve through dialogue and education.

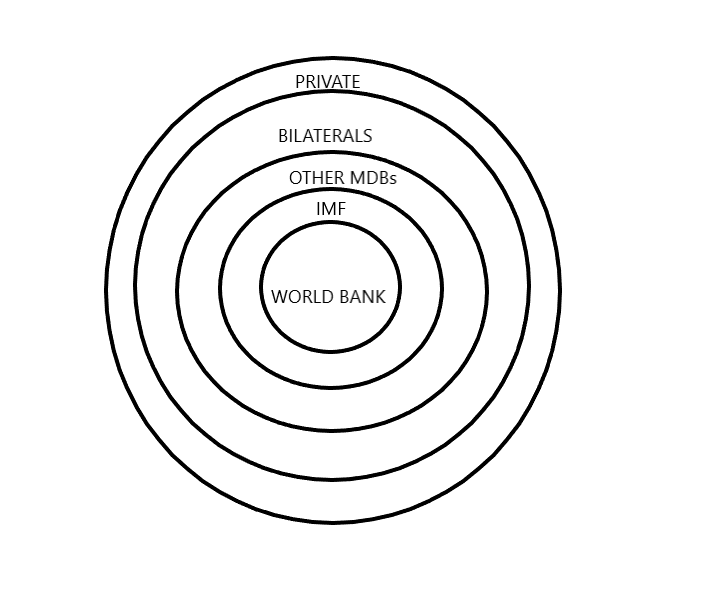

When it comes to the World Bank’s ability to achieve greater creditor coordination around the SDFP, it would be useful to think of concentric circles of engagement (see Figure 4). This reflects both priority of engagement for the bank and realism about what can be achieved among groups of creditors.

Figure 4. Creditor coordination under SDFP requires creditor prioritization

The IMF represents the inner circle of engagement, representing existing practice under the NCBP and debt policy issues more generally. There are some areas of needed improvement in this relationship, however.

First, there is a case for more World Bank leadership under the SDFP to provide an “early warning” about country cases in World Bank-IMF dialogues. This need reflects the fact that IMF is necessarily engaged in high risk countries, those seeking IMF financing due to balance of payments problems, whereas the World Bank is working with the full array of developing country partners. In principle, this means the bank is in a stronger position to identify debt risks early.

Second, the NCBP review indicates “when the IMF grants waivers under the DLP, the NCBP committee typically followed suit to maintain consistency with the IMF.”[13] This ex-post approach seems sub-optimal compared to active coordination during the decision-making process. It also may reflect a broader set of tensions between the two institutions around NCB issues—for example, the IMF’s use of general external debt limits on present value terms versus strictly NCB limits and how these inform the application of conditionality. Though the general working relationship and coordination appears to be strong, reflected in staff interviews in both institutions, there remains room for better coordination.

Though not yet public, it will be telling to see the degree to which coordination issues with the World Bank factor into the IMF’s current review of its Policy on Public Debt Limits (DLP). In order to be effective, both the World Bank’s SDFP and the IMF’s DLP will need to be well coordinated on key questions—for example, assessing proposed non-concessional projects for development impact; or, taking a consistent approach to assessing the effects of project collateralization on loan concessionality;

The next circle of engagement pertains to peer multilateral lenders. Here, there is little evidence of harmonization and coordination of effort around SDFP issues. Of course, there is policy diversity on a large number of issues (procurement rules, safeguards issues, etc.) across these institutions, but debt sustainability ought to be an area of commonality. Even on issues that accommodate some variation in practice, such as procurement policy, the underlying principles are shared to a degree that variations do not undermine common development objectives, and there are some joint elements to the policies. For example, the MDBs’ anti-corruption policies include a shared “cross-debarment” agreement which stipulates that firms debarred from one MDB is debarred from all.[14]

The survey evidence from the NCBP review offers little to suggest that even a core set of principles, let alone binding joint actions, are widely shared across the MDBs. If there is scope for rapid progress on SDFP creditor coordination, it is surely among these institutions.

The next circle of engagement pertains to bilateral creditors. Here, the current crisis may present an opportunity for strengthening SDFP objectives. As of this writing, the G20 agreement on a debt standstill arrangement among bilateral creditors represents progress when it comes to coordination but also points to deepening engagement among these creditors in the months ahead to sort out the need for debt forgiveness among IDA countries. The outcome may point to a new arrangement building on the long-standing Paris Club, this time with China and other non-traditional creditors at the table. In a crisis context of widespread IMF programs, it is likely the Fund will take a leading role in engaging with bilateral creditors, but it will be important that the World Bank also play an anchor role on behalf of the SDFP.

Whatever emerges from the current crisis on debt forgiveness also has potential for better coordination with private creditors. At present, this element of the G20’s action plan is the least defined, reflecting long standing challenges of coordinating different types of private creditors (bond holders, commercial banks, other private lenders). A status quo outcome points to a wave of defaults on commercial debts, with debt write downs proceeding country-by-country in the context of IMF programs, with the risk of “hold-out” creditors pursuing legal claims long after the crisis is over. More robust official action could point to enforced coordination mechanisms through UN resolutions and legal actions in key jurisdictions.[15] To the degree a new coordinating architecture emerges for these creditors, the World Bank should make full use of it when it comes to the SDFP.

Finally, when it comes to bilateral commercial creditors together, the World Bank has raised concerns in recent years about the erosion of the bank’s preferred creditor treatment due to borrower violations of the negative pledge clause contained in IBRD and IDA loan contracts. Preferred creditor treatment is fundamental to the institution’s financial model and particularly the ability to lend at low cost in high risk environments, so any erosion is a significant cause for concern. Among other things, erosion could take the form of non-pari passu repayments by creditors in arrears; emergence of new creditors; increased use of collateral by bilateral and commercial creditors; and increased risk-sharing by MDBs with market creditors. Among these, the World Bank and IMF have begun to document the use of collateral provisions in loan contracts among non-traditional creditors, pointing to the complications and risks of these provisions when it comes to debt workouts and the ability of the Bank and Fund to provide appropriate crisis response.[16] Depending on the post-crisis architecture, the SDFP could play an organizing role in seeking new commitments among creditor groups to constrain activities and loan provisions that disrupt the goals of sustainable finance and the ability of preferred creditors like the Bank and Fund to operate effectively.

Key recommendations for implementation of the SDFP

1. Clear Delineation of Crisis and Post-Crisis Implementation

Crisis demands in 2020 and potentially beyond create challenges for full implementation of the SDFP, particularly on Pillar 1 issues. The full suite of engagement measures with IDA countries simply won’t be possible given resource constraints and the need to prioritize crisis measures. And the financial incentives and disincentives encapsulated in the new set aside arrangement is at odds with the need to front load crisis resources, at least for the next year. Given these competing objectives, there is considerable risk that the inaugural SDFP proceeds in a compromised fashion without acknowledgement that this is the case, making it more difficult in the future to assess the degree to which the policy is working as intended. To avoid this problem, it would be best for World Bank management to delineate clearly where departures from the new policy, even upon introduction, are needed for crisis purposes. This will help to protect core principles over time.

2. Early Stage IEG Assessment

There should be an early-stage assessment of the SDFP from the bank’s Independent Evaluation Group (IEG). An assessment of the Program for Results (P4R) lending instrument was conducted by IEG after three years of P4R operations, covering the 2013 to 2015 period.[17] At the time of the P4R assessment, the IEG emphasized certain limitations in its ability to assess outcomes given the preliminary nature of the work. However, the assessment proved useful in scrutinizing P4R project design in country programs, particularly the design and use of disbursement linked indicators. The indicators play a key role in P4R and were the subject of considerable debate and scrutiny when the bank’s board was considering the P4R proposal in 2012.

This experience is relevant for consideration of SDFP, which depends significantly on the use of indicators to determine the release of funds under country programs and prioritization of Bank resources to support the SDFP. The board should request an early stage IEG assessment of the SDFP to be completed as an input for IDA-20 discussions. The IEG will have up to two years of performance of the policy to assess according to three key dimensions.

- First, did the first two rounds of SDFP indicators prove to be rigorous, well targeted, and measurable in their design according to an independent assessment? This dimension is particularly well aligned with the IEG’s P4R work, where concerns from the board suggested that the incentives of P4R borrowers and bank staff could favor weaker standards (ie, low thresholds for lending disbursements).

- Second, did the initial year of country performance demonstrate responsiveness to the objectives of SDFP, as posited through the indicators and more broadly? An early-stage assessment on this dimension is important to allow for a timely course correction in the event there are clear problems with the indicators or the scale of the set asides.

- Finally, the IEG could usefully assess how well the bank has aligned staff resources, budget, and prioritization of SDFP issues within country programs. For example, was there in an increase in budget for the provision of technical assistance to support country capacity? Was there evidence that debt management issues were prioritized in country programs by the country teams? This dimension could be particularly useful, both because it lends itself to measurement (e.g., budgeting inputs) and it is also an area where the SDFP is particularly vague in articulating commitments on an ex ante basis.

The board should also consider incorporating SDFP Pillar 2 issues in the IEG request. Given the vague nature of the bank’s commitments around creditor outreach, any independent assessment of these activities could prove useful. The IEG could use survey instruments to assess awareness of and responsiveness to the SDFP in the broader creditor community. This information would be a useful supplement to the reporting the board should expect from bank management (eg, use of the lending to LICs mailbox in terms of number and diversity of creditor requests for information).

3. Country Program Assessment Criteria for Board Members

Success of the SDFP will be borne out in country programs. As a result, board oversight of each country program is important. There are basic questions that can serve as useful framing for oversight of Pillar 1 activities for each country:

- What is the evidence that the performance indicator(s) is addressing the leading constraint to better debt mgt practice?

- What is the case for change in the year ahead (theory of change)? Demonstrate evidence of commitment by the IDA partner government.

- How will these efforts be resourced/supported?

- How does this approach compare to efforts in other countries?

4. More Frequent DeMPAs; More Resourcing of Debt Diagnostics and Assistance

The core “set aside” framework of the SDFP’s Pillar 1 rests on the proposition that the World Bank can make progress in assisting its IDA clients in effective debt management practices. But the uses of IDA financial incentives and disincentives alone is unlikely to drive change. In cases where there is significant political will to improve debt management, capacity development requires timely diagnostic exercises and substantial technical assistance. The DeMPAs are a valuable diagnostic tool, but they lack adequate country reach and timeliness. There is only one publicly available DeMPA report for 2019 and other “current” reports date as far back as 2010.[18] As dated as the published reports are, they cover fewer than half of IDA countries. In short, there needs to be a significant push toward greater ambition for the DeMPA exercise, particularly given the debt challenges posed by the current crisis. The bank should work with its shareholders to identify an appropriate funding model to sustain a more robust diagnostic function.

Adequate resourcing pertains more broadly to technical assistance. In the months ahead, donor countries will likely be called upon to financing debt relief through various means. For example, the IMF has already made an appeal to donors to support the Catastrophe Containment and Relief Fund, which provides payment relief to low income IMF borrowers. These donor countries will also be under pressure to relieve their bilateral credits, moving beyond the debt standstill arrangement announced in April 2020. Recognizing the substantial costs of HIPC-style debt relief measures, World Bank shareholders should better appreciate the long-term value of modest contributions to debt management efforts, particularly following a period when the technical complexity has increased significantly.

The multi-donor Debt Management Facility (DMF), which supports the DeMPAs along with other technical assistance activities, is the primary resourcing platform for these activities at the bank and yet has a relatively small donor base. It is debatable whether a donor-dependent trust fund model is appropriate to these core capacity activities, but if this continues to be the model, it should be broadly supported and adequately financed. Existing donors like the German government, along with World Bank and IMF management, should appeal to a wider array of potential donors in the months ahead.

5. Convening by World Bank of SDFP Official Creditors Forum

One uncertain effect of the current crisis is the degree to which it will force a new alignment of creditors, either building on current arrangements anchored by the IMF, World Bank, and Paris Club, or by some new alternative architecture. It is also possible that no formalized arrangement will emerge, and the crisis drives further deterioration in the capacity of current arrangements to manage debt problems. Either way, it remains the case that Pillar 2 of the SDFP lacks clarity and ambition when it comes to navigating a fractured and uncoordinated creditor landscape. It takes a passive approach in key respects, hoping for example, that non-Paris Club countries like China would simply join the Club.

Given the uncertainties ahead, the World Bank should be proactive on behalf SDFP objectives, recognizing the window of opportunity afforded by the crisis. Together with the IMF, the World Bank will see its influence increase during the crisis period. IDA borrowers will be more reliant on the Bank and IMF as other sources of financing become scarcer. And the creditor community will be more engaged with the World Bank and IMF as these institutions seek to facilitate coordination around a complex array of distressed situations.

The G20 bilateral creditor actions in support of a debt payment standstills represents a tentative step toward coordination, but it is fragile and risks the lack of further momentum toward more comprehensive efforts. It seems unlikely that the composition problems of the Paris Club, or the tentativeness of the G20 generally, will shift dramatically toward more coordinated action, and instead we are likely to see ad hoc solutions to debt problems on the part of bilateral and private creditors. In this environment, the position of the World Bank and IMF together could be stronger if these institutions are willing to act strategically.

Namely, the World Bank, working with the IMF, should seek to organize a standing meeting of IDA creditors, prioritizing creditors according to the concentric circles in Figure 4. Something like this may in fact emerge from the crisis itself, but a formalization of the convening should be adopted explicitly as an element of SDFP Pillar 2. Absent such a forum, it remains unclear how key creditor groups—bilateral creditors and even MDBs as a group—will self-organize in order to identify SDFP-like practices and standards that bind across institutions. The agenda of such convenings should be concrete and action oriented, focused on translating SDFP objectives as well as high level commitments reflected in the G20 sustainable lending principles into operational policies among all creditors at the table. In driving this convening and agenda, the World Bank and IMF could seek to bring creditor policies in line with their own core frameworks. For example, the mooted position at such a forum could be for the DSA traffic light system to be a binding constraint on other creditors’ lending policies.

Conclusion

The World Bank’s new sustainable development finance policy represents a well-considered and serious effort to better engage IDA client countries and their broader community of creditors to promote debt sustainability. The need for a new policy was already clear before the COVID-19 pandemic, as a growing number of IDA countries were facing significant debt vulnerabilities.

A fundamental challenge for the new policy rests in the question of whether the World Bank has sufficient leverage to affect change among its IDA clients and across the creditor community when it is no longer a dominant, or in some cases, even a leading creditor. The performance of the NCBP is discouraging in this regard. And while many of the features of the new policy are sensible, they do not fundamentally alter this basic challenge.

In one sense, the current crisis presents an opportunity. IDA financing itself will become more important for countries effected by the crisis, particularly as other sources of financing (and particularly sources of non-concessional financing) become scarcer. As a result, the World Bank will be in a stronger position to promote the objectives of the SDFP. Of course, it is also a difficult period in which to pursue the SDFP, recognizing that some features of the policy may run at cross purposes with effective crisis response, at least in the near term.

Nonetheless, it remains the case that, as with the NCBP, the SDFP faces significant risk that key debt dynamics may remain beyond the reach of the World Bank itself. As the SDFP indicates, the primary responsibility for sustainable borrowing practices lies with the borrowing countries themselves. However, in a critical sense, the success of the SDFP is subject to a set of risks that the policy itself does not acknowledge.[19] Namely, will the Bank marshal the internal resources necessary to support its IDA clients? For the World Bank board, it will be critical to probe the various dimensions of this question, as outlined throughout this review.

[1] “IDA’s Non-Concessional Borrowing Policy 2019 Review,” Board Paper, World Bank, October 8, 2019.

[2] “IDA19: Ten Years to 2030: Growth, People, Resilience,” Annex 9, Board Paper, World Bank, February 11, 2020; “Sustainable Development Finance Policy (SDFP) of the International Development Association,” Board Paper, World Bank, April 23, 2020.

[3] See Annex II of G20 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors Communique, April 15, 2020.

[4] See “The Evolution of Public Debt Vulnerabilities in Low Income Economies,” Joint Paper prepared by World Bank and IMF, January 10, 2020.

[5] IDA19, Annex 9, February 11, 2020; Board Paper, April 23, 2020.

[6] “IDA’s Non-Concessional Borrowing Policy 2019 Review,” IDA Board Paper, September 26, 2019.

[7] Ibid., p. 19.

[8] Ibid., p. 14.

[9] Ibid., p. 23.

[10] Masood Ahmed, “Spend What It Takes to Fight COVID-19 in Poor Countries, Too,” Devex, March 25, 2020.

[11] Board Paper, April 23, 2020.

[12] IDA’s Non-Concessional Borrowing Policy Review, 2019, paragraph 38.

[13] IDA’s Non-Concessional Borrowing Policy 2019 Review, Paragraph 32.

[15]https://ftalphaville.ft.com/2020/03/25/1585171627000/From-coronavirus-crisis-to--sovereign-debt-crisis/

[16] “Collateralized Transactions: Key Considerations for Public Lenders and Borrowers,” World Bank and IMF staff paper, January 23, 2020.

[17] “Program for Results: An Early Stage Assessment of the Process and Effects of a New Lending Instrument,” IEG, World Bank, 2016.

[19] The articulation of risks in the April 23rd Board paper (pp. 18-19) focus exclusively on external factors and do not address any aspect of institutional failure on the part of the World Bank itself.

Rights & Permissions

You may use and disseminate CGD’s publications under these conditions.