Recommended

Introduction

Financial inclusion is a fundamental pillar of development. Access to financial products and services broadens economic opportunities for individuals and firms and helps governments design and deliver transfers more effectively. For policymakers, increasing financial inclusion is a tool to accelerate growth, reduce inequality, and boost productivity for small and medium-sized enterprises.

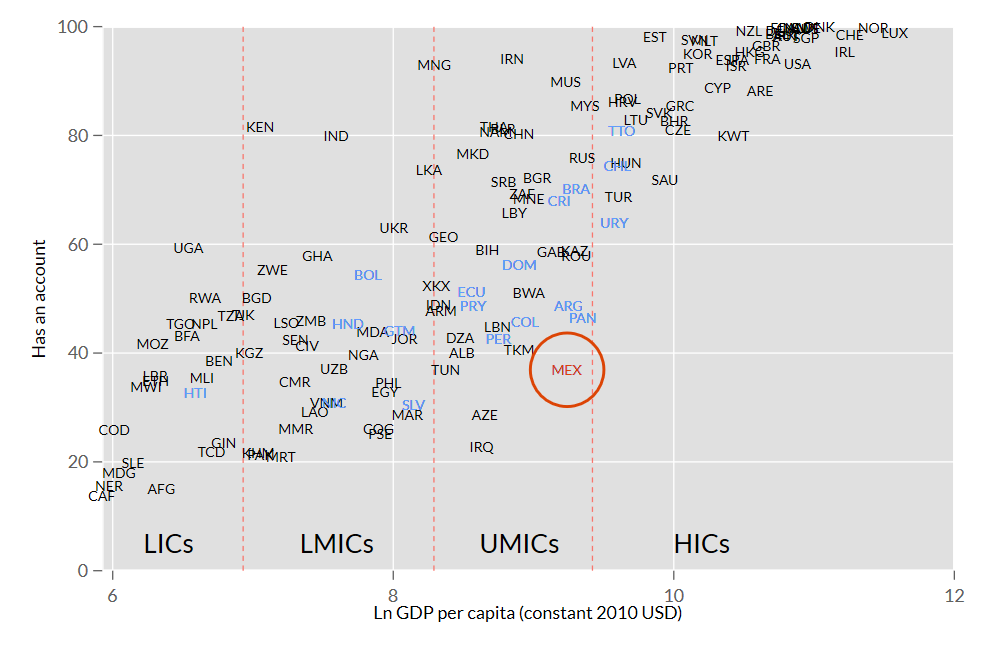

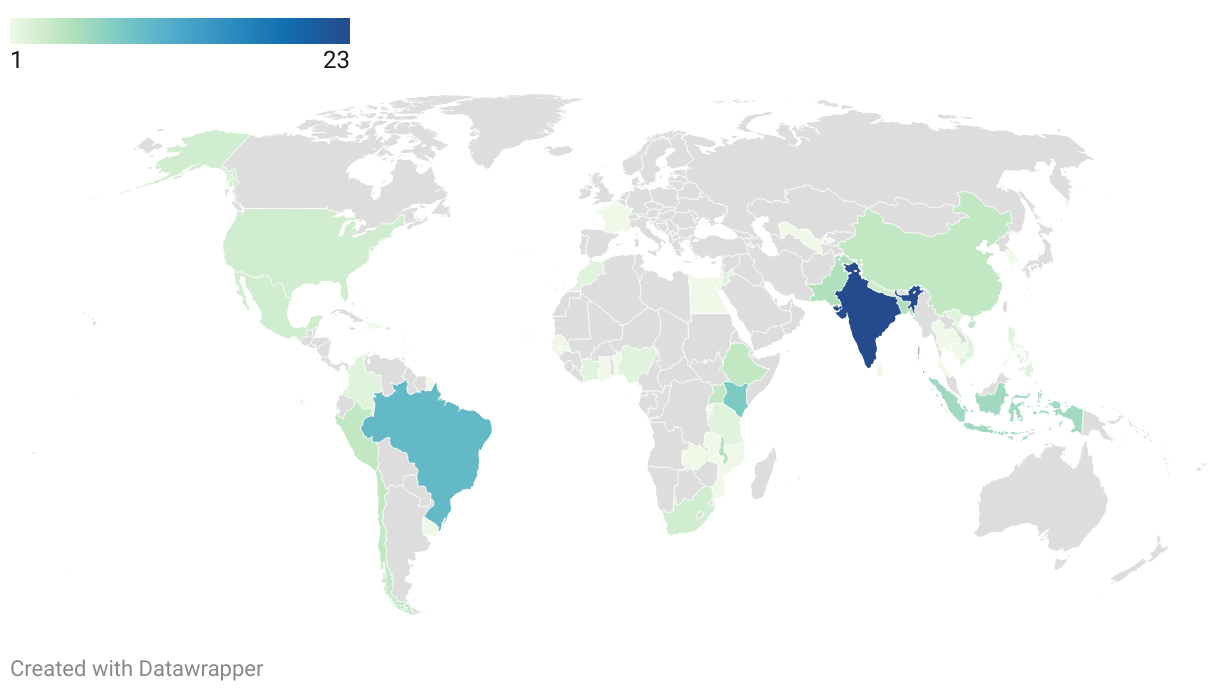

Mexico poses a conundrum. In many respects it has been successful at growing its economy and integrating with global markets. On the other hand, its level of financial inclusion, at 36.9 percent, is about 20 percentage points lower than for other countries at comparable levels of per capita income, and is far below the level in such lower-middle-income countries as Kenya and India (Figure 1). Among its peers in Latin America, Mexico is the worst-performing relative to its income; it only surpasses three other countries regionally—all with much lower per capita incomes.

Figure 1. GDP per capita and financial inclusion

Latin America and Caribbean countries in blue, Mexico in orange and circled.

Source: Findex 2017 (Demirgüç-Kunt et al., 2018) and World Development Indicators 2017.

Mobile money has been a boon for financial inclusion in many low- and lower-middle-income countries. For example, in both Kenya and Uganda, 26 percent of adults are financially included via a mobile money account alone. In Côte d’Ivoire, a low-income country, mobile money accounts for almost two-thirds of financial inclusion among adults, while in upper-middle-income Paraguay, this proportion is a little over one-third. Mobile money can clearly have a large impact on financial inclusion when policy and infrastructure conditions are right. But why is it not having an impact in bridging the inclusion gap in Mexico? In this policy note, we consider these questions, suggest answers, and propose policies to address these gaps.

Why is financial inclusion so low in Mexico?

Several factors appear to contribute to Mexico’s low financial inclusion, on both the demand and supply sides, but the overall portrait that emerges is of a banking sector that is not especially interested in or incentivized to serve the needs of poor customers.

Both international and national surveys of consumers point to insufficient or variable income as a major self-reported reason on the demand side for not opening a bank account. Two other factors—low workforce participation and poor perceptions of the banking sector—appear to contribute to low demand for financial services. Figure 2 shows how workforce participation is associated with higher levels of financial product consumption in Mexico. This is to be expected because workplaces often make payments through direct deposit and face pressure from the government to formalize their accounting practices. However, much of the labor force works in informal settings, especially in rural areas; additionally, women are less likely to have access to formal jobs.

Figure 2. Adult financial product uptake by labor force participation (percentage)

Source: Findex 2017 (Demirgüç-Kunt et al., 2018).

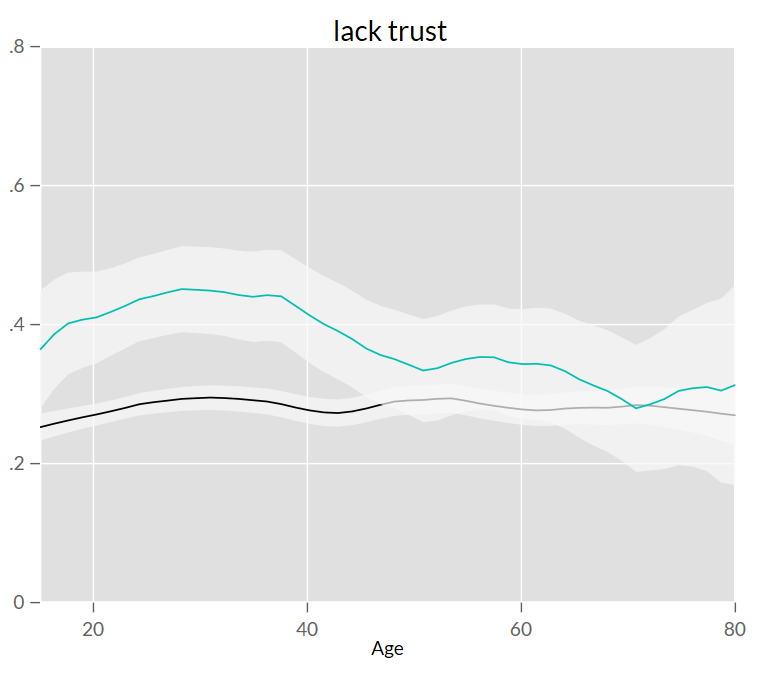

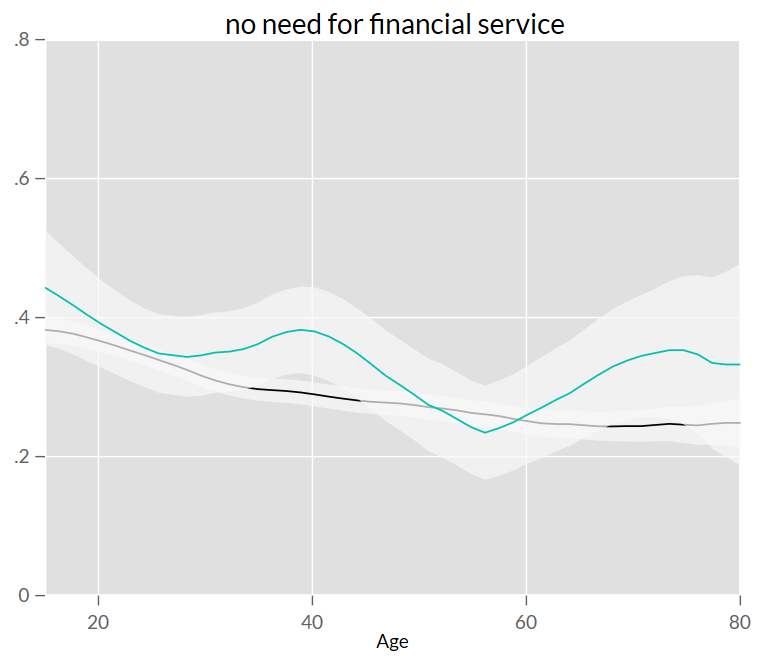

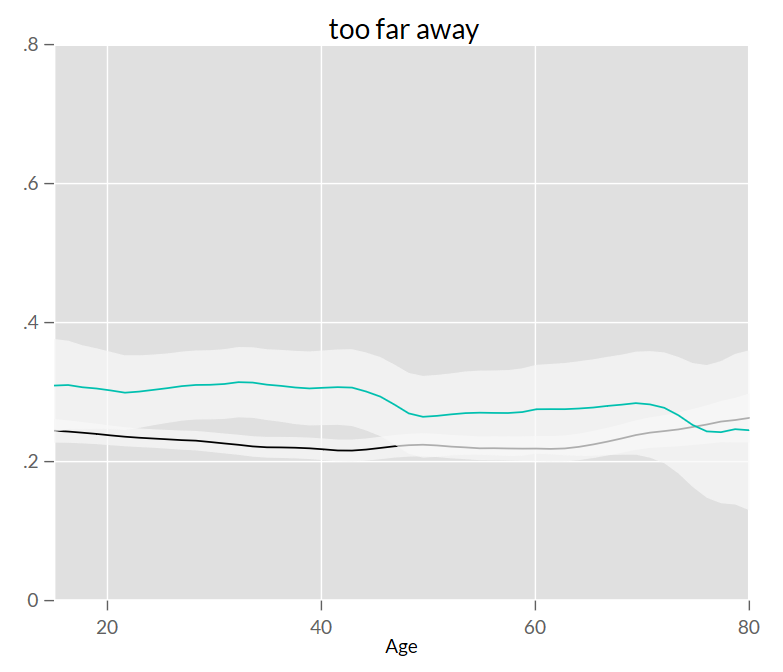

Likewise, how people perceive banks influences financial inclusion. Thirty-seven percent of Mexican adults without an account say that lack of trust in financial institutions is a factor; the same proportion report that that they do not have an account because they do not need one (Demirgüç-Kunt et al., 2018; ENIF 2018). This trust deficit could be rooted in bank failures of the recent past. Risky behavior by banks combined with weak enforcement of property rights contributed to the collapse of the financial system in 1996-7 and an estimated 1.75 million people participated in debtor relief programs (Haber, 2005). Figure 3 shows that Mexicans under the age of 45 have much less trust in the banking system in comparison to similar cohorts in the rest of Latin America. In addition, Mexicans between the ages of 37 and 43, as well as between 67 and 75, are more likely to report they do not need financial services.

Figure 3. Demand-side reasons for not having an account: Mexico (green) vs. Latin America & Caribbean (black)

Graphs show probability of citing reason calculated using locally-weight polynomial regression; error bars represent 95 percent confidence intervals.

Source: Findex 2017 (Demirgüç-Kunt et al., 2018).

Turning to the supply side, fees, commissions, and interest rates charged by banks appear to be serious barriers for many of the unbanked in Mexico, as well as severe logistical costs to access services (echoed in Fouillet and Morvant-Roux, 2018). For example, according to financial inclusion data[1] from the National Banking and Securities Commission (CNBV, by its Spanish acronym) bank branch coverage is especially low in rural areas, with only 0.66 ATMs per 10,000 residents in rural areas compared to 2.7 ATMs per 10,000 residents in urban and semi-urban municipalities. Even worse, rural ATMs are heavily concentrated, so that 87 percent of rural municipalities lack an ATM. Getting to a bank branch or ATM to access or deposit money is costly, in terms of both time and money, for many potential customers, and this is reflected in the 21 percent of Findex respondents who say they do not have an account because of poor financial infrastructure nearby (Demirgüç-Kunt et al., 2018).

One might expect that banks would customize products to meet demand for financial services across different segments of the population. In theory, this should be easier among lower-income segments because Mexico has implemented a tiered Know-Your-Customer (KYC) regulatory framework with less rigorous requirements for lower-value accounts. However, looking at financial inclusion by income quintile shows that the only group where a majority owns accounts is the richest 20 percent (see Figure 4). The market segmentation process carried out by many financial institutions could contribute to the status quo that effectively excludes a large segment of the population from financial services. Large banks have limited their lending activities to large established corporations, constraining access to informal and small and medium-sized firms.

Figure 4. Percentage of adults with a bank account by income quintile

Source: Findex 2017 (Demirgüç-Kunt et al., 2018).

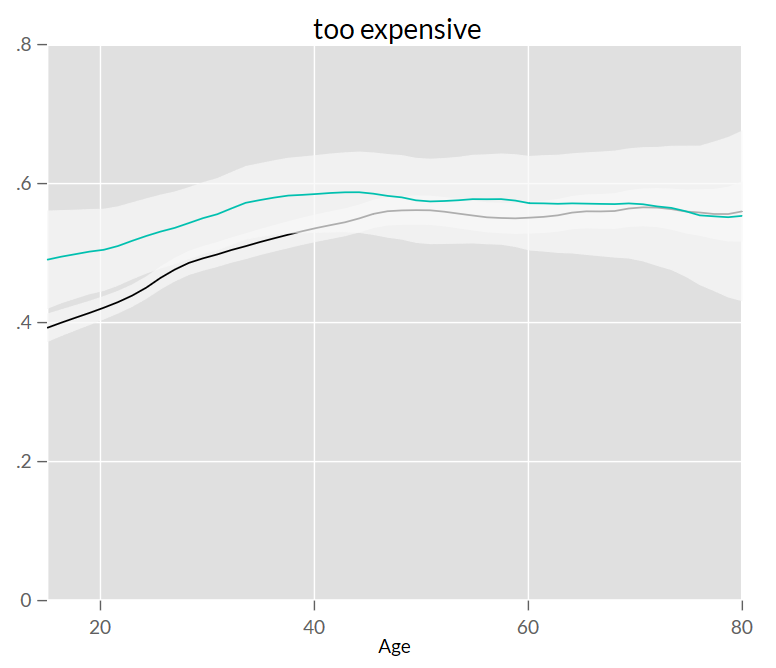

Comparing Mexico to the rest of Latin America provides further evidence of the importance of supply-side barriers. Figure 5 shows how Mexicans from ages 15 to 38 are more likely to say that bank account expenses are too high compared to the rest of Latin America. Potential Mexican customers from age 25 to 45 are also more likely than their Latin American peers to cite distance, as well as cost, as an impediment to account uptake. Retail banking marketing practices at Mexico’s largest banks are geared towards middle- and higher-income segments that represent the most significant profit pools for those banks. Sparse rural bank branch and ATM coverage represent choices made by banks, and the imbalances provide an observable indicator of where banks believe their desirable customers are located.

Figure 5. Supply-side reasons for not having an account: Mexico (green) vs. Latin America & Caribbean (black)

Graphs show probability of citing reason calculated using locally-weight polynomial regression; error bars represent 95 percent confidence intervals.

Source: Findex 2017 (Demirgüç-Kunt et al., 2018).

Discrimination on the basis of ethnicity may be a further factor. A recent experiment by Martínez Gutiérrez (2018) provides evidence of discrimination by banks based on skin color, which impacted offers of credit lines to customers, supporting the notion of bias against the low-end market segments which tend to include proportionately more people who are indigenous or mixed race. And, while a range of research suggests that government transfers that target the poor can be a potent force to increase financial inclusion, Fouillet and Morvant-Roux (2018) note that for Mexico, steep eligibility cliffs at the edges of targeted populations lead to substantial coverage gaps for people in fragile situations.

Even with all these explanations on both demand and supply sides, we would expect that latent demand for financial services would drive customers towards mobile money options, particularly because of the geographical access barriers to banking. In the next section, we explore why this is not occurring and the suboptimal substitutes that may be filling some of the gaps.

Why isn’t mobile money making up the gaps?

As an upper-middle-income country where 90 percent of adults have an ID, 60 percent own a mobile phone (Demirgüç-Kunt et al., 2018), and 95 percent of the population is covered by at least a 3G signal (GSMA, 2019), Mexico appears to have the foundational components in place to make mobile money a viable alternative to conventional banking. Instead, only 4.1 percent of adults reported having used a mobile money account in the previous year. We find two likely drivers behind this dynamic: regulatory capture by banks and the presence of financial products that provide partial substitutes.

Regulatory factors. Mexico’s very low rates of mobile money usage is in sharp contrast to Kenya, where 84.8 percent of adults are financially included and 76.9 percent report having used a mobile money account. Suarez (2016) compares the two countries and asserts that the Mexican government’s regulatory approach to mobile money has been a byproduct of regulatory capture that favors the status quo preferred by banks. Mobile network operators (MNO) requested the government to develop mobile money-specific regulations, but the government required them to be licensed as banks. In contrast, the Kenyan regulators permitted the emergence of payments services operated by MNOs, subject to arrangements to hold counterparts to deposits in trust with the banking system. As a result, the Mexican MNOs have not been able to extend similar low-margin/high-volume services to the unbanked population.

Recent regulatory changes may help to address the current barriers to entry. The FinTech Law of 2018 was passed to promote innovation and define capital requirements and transaction limits, as well as to create regulatory sandboxes—limited testing grounds that allow fintechs to innovate new approaches without having to comply with, or be supervised by, all regulatory institutions (Perez, 2018; Harris and Barr, 2019). Early signs from a survey of fintech firms suggest that over half of their customers are unbanked/underbanked consumers and small- and medium-sized enterprises (Perez, 2018). Simultaneously, the central bank recently launched the Cobro Digital System (CoDi), an interoperable payment switch, although this requires users to have an account with a formal bank and a smartphone to scan QR codes (Eschenbacher and Irreratest, 2019; Mexicanist, 2019). While the long-term goal is to facilitate competition with the banks by fintech platforms, the initial rollout may still face some of the existing bottlenecks.

Kenya provides an interesting comparison case. Ndung’u (2019) describes four stages of digitization of financial services. Stage one involved the emergence of a widespread mobile platform for person-to-person transfers built on 2G technology and a nationwide MNO agent network for cash-in-cash-out services. The second stage saw the mobile platform integrated with commercial banks, which benefited from easy deposit-making through the mobile payments platform. Stage three added virtual savings accounts and credit facilities to the mobile payments platform, while the fourth stage incorporated cross-border payments. Mexico’s FinTech Law of 2018 appears to extend through the third stage, but two key differences stand out as potentially exclusionary. First, requiring a bank account to access a payments platform limits the potential fintech market to people who can already access finance. Second, the technical requirements of the CoDi switch suggest that a smartphone will be the minimum level of technology required to access its functionality—which excludes cheaper 2G mobile phones. While there are some encouraging signs that the regulatory context is loosening in a way that will allow for mobile-driven platforms to contribute more substantially to financial inclusion, there still seem to be some bottlenecks to be resolved.

Substitute financial products. Financial inclusion, as generally defined, involves ownership of a transacting account where a consumer can deposit, withdraw money, make payments, and potentially be able to access credit facilities. In Mexico, however, 62 percent of adults access credit without a transacting account via retailer-issued credit cards (an increase from 49 percent in 2006), almost twice as many as those who use bank credit cards—see Figure 6 (Caskey, Ruiz Duran, and Maria Solo, 2006). Credit is used to finance purchases at the retailer who issues the line of credit. The cards come with lower minimum income and ID requirements than bank-issued credit cards.

These retailer credit cards are important because they are designed specifically to meet the credit constraints of middle- and lower-income segments of the population who have been otherwise ignored by the banks. Marambio-Tapia (2017) describes how they function in the Chilean household context, where department stores, supermarkets, and other retailers tap into unbanked populations and offer them what is often their first formal financial product. Beyond simply targeting lower-income strata, retail stores offer a more convenient option than banks because they carry a wide variety of items that customers need and offer longer working hours. Marambio-Tapia additionally notes that when banks did begin to provide competing financial products to these customer segments, they did so via separate brands that differentiated high-status customers from previously unbanked customers. He suggests that “[t]his brand stretching helped banks increase their scope without affecting their brand. It avoided mixing new customers with old customers, as the former could alienate the latter.” These dynamics resemble many of those observed in Mexico and the experience is suggestive of a similar pattern.

Figure 6. Formal credit products used by adult population (percentage)

Source: ENIF 2018.

In both the Mexico and Chilean cases, it is important to keep in mind that these retailer credit cards are not designed as social enterprises. They involve higher fees and interest rates than banks, as well as other, hidden costs, and occasionally they bundle services of dubious legality (Perez and Reichow, 2017; Marambio-Tapia, 2017). Likewise, the limited nature of these credit cards means that customers can only use them to purchase items at the issuing retailer—they are not general-purpose payment cards. As such, they cannot be used for business credit, to pay for education, or to cover health expenses. It appears that these retailer credit cards are meeting some of the demand for financial services in Mexico of the lower-income population; nevertheless, they should not be considered adequate for financial inclusion. The lack of even a savings product negates their flexibility for consumption smoothing or dealing with sudden shocks, which severely reduces their utility as a financial instrument. In other words, it appears that retailer credit cards are closing one narrow component of the financial gaps left by banks, but not enough to be considered financially inclusive instruments.

Policy recommendations

Mexico has several policy levers and vectors to promote financial inclusion, but first the government needs to ensure that the market fundamentals are correct.

Level the financial playing field. Mexico’s financial sector model has historically been bank-led and needs to encourage more competition and innovation to extend coverage to poorer customers. The interoperable CoDi switch ought to be a step in the right direction, but it still requires a smartphone to scan QR codes and an account with a formal bank, which leaves potential customers subject to all the constraints discussed above. The FinTech Law of 2018 could introduce more competition, although the relative lack of oversight could backfire if firms take on excess risk and expose customers to losses. Simultaneously, fintech firms are handicapped by the inability to take deposits and thereby rely on banks for this component of their services (Perez, 2018). Finally, fintechs need to also extend their services to mobile money (not just internet-enabled mobile banking), which can be built on minimal technologies like 2G mobile. Balancing regulatory priorities with enough space for innovation is always a delicate task but leveling the playing field so that small players can enter and compete should be a near-term priority.

Policy interventions. Governments have proactive policy levers at their disposal to promote financial inclusion. India boosted adult financial inclusion by almost 45 percentage points from 35.2 to 79.9 percent over six years, in part due to the government’s push to open bank accounts under the Jan Dhan Yojana program (Demirgüç-Kunt et al., 2018). Mexico appears to have a risk-based KYC regulatory framework in place to ease access to bank accounts, but there still seems to be a dearth of will on the part of the banks themselves to participate.

Absent substantial private sector buy-in, the government might have to make a push itself to see gains in financial inclusion. The Mexican government has an admirable record for delivering social transfer programs, suggesting that it has the capacity to achieve ambitious financial inclusion goals. The current administration has taken steps to route several cash transfer programs via the banking system and thereby promote bank account uptake. However, these initiatives will be constrained by all the access limitations of the incumbent bank-led model unless the FinTech Law of 2018 leverages technology to lower entry barriers and level the playing field.

Conclusion

While Mexico has a long way to go to close its enormous financial inclusion gap, we are optimistic about the direction of change in the policy environment. Understanding why the gap exists is an important first step. We argue that it comes from a combination of demand factors (lack of trust in banks, low incomes, a large informal economy) and supply factors (sparse physical infrastructure, lack of interest in poor customer segments, discrimination, and too narrowly targeted government social transfers). We find that mobile money has so far not contributed substantially to financial inclusion because it has been handicapped by bank-centric regulation and possibly also the presence of restrictive credit substitutes. Even so, we remain open to the possibility that recent legislative and regulatory moves will provide the space necessary for fintech and mobile money operators to rapidly scale up their services as we have seen elsewhere in the world.

Thanks to Alejandro Fiorito Baratas and Diego Castrillón for their comments and feedback.

References

Caskey, J. P., Ruiz Duran, C., & Maria Solo, T. (2006). The Urban Unbanked In Mexico And The United States. Policy Research Working Papers. Retrieved from https://works.swarthmore.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1355&context=fac-economics

Demirgüç-Kunt, A., Klapper, L., Singer, D., Ansar, S., & Hess, J. (2017). Global Financial Inclusion and Consumer Protection Survey, 2017 Report. https://doi.org/10.1596/28998

ENIF. (2018). Encuesta Nacional de Inclusión Financiera (ENIF) 2018 [Dataset]. Retrieved November 7, 2019, from https://www.inegi.org.mx/programas/enif/2018/default.html#Documentacion

Eschenbacher, S., & Irreratest, A. (2019, February 19). RPT-Mexico pushes mobile payments to help unbanked consumers ditch cash. Reuters. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/article/mexico-fintech-unbanked-idUSL1N20D0GZ

Fouillet, C., & Morvant-Roux, S. (2018). Financial inclusion, a driver of state building in India and Mexico? International Development Policy | Revue Internationale de Politique de Développement, 10(10.1). https://doi.org/10.4000/poldev.2519

GSMA. (2019). GSMA Mobile Connectivity Index. Retrieved October 30, 2019, from GSMA Mobile Connectivity Index website: https://www.mobileconnectivityindex.com/

Haber, S. (2005). Mexico’s experiments with bank privatization and liberalization, 1991–2003. Journal of Banking & Finance, 29(8), 2325–2353. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2005.03.017

Harris, A. A., & Barr, M. S. (2019). Central Bank of the Future (Working Paper No. 1). Retrieved from University of Michigan Center on Finance, Law & Policy website: http://financelawpolicy.umich.edu/sites/financelawpolicy.umich.edu/files/filefield_paths/cbotf_paper_1_-_07.08.19.pdf

Lambert, F., & Park, H. (2019). Income Inequality and Government Transfers in Mexico [IMF Working Paper]. Retrieved from International Monetary Fund website: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2019/07/11/Income-Inequality-and-Government-Transfers-in-Mexico-47015

Marambio-Tapia, A. (2017). Narratives of Social Mobility in the Post-Industrial Working Class and the Use of Credit in Chilean Households. Revue de La Régulation. Capitalisme, Institutions, Pouvoirs, (22). https://doi.org/10.4000/regulation.12512

Martínez Gutiérrez, A. L. (2018). ¿Quién tiene acceso al crédito en México? Discriminación por color de piel en el mercado crediticio mexicano [Doctoral Thesis]. Retrieved from Centro de Investigación y Docencia Económicas website: http://repositorio-digital.cide.edu/handle/11651/2723

Mexicanist. (2019, October 30). Banxico presents CoDi, the new mobile payments platform [News]. Retrieved November 7, 2019, from Mexicanist website: https://www.mexicanist.com/l/banxico-codi-mobile-payments-platform/

Ndung’u, N. (2019). Digital Technology and State Capacity in Kenya (Policy Paper No. 154; p. 43). Center for Global Development. Retrieved from /sites/default/files/digital-technology-and-state-capacity-kenya.pdf

Perez, M. (2018). Mexico’s Nascent Fintech Offers Promise, Faces New Rules. Southwest Economy, (Q4), 12–15. Retrieved from https://ideas.repec.org/a/fip/feddse/00143.html

Perez, M., & Reichow, K. (2017). Mexico’s ‘SOFOM’ Finance Firms Attempt to Broaden Loan Availability. Southwest Economy, (Q4), 4. Retrieved from https://www.dallasfed.org/~/media/documents/research/swe/2017/swe1704e.pdf

Suárez, S. L. (2016). Poor people׳s money: The politics of mobile money in Mexico and Kenya. Telecommunications Policy, 40(10), 945–955. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.telpol.2016.03.001

Villarreal, M. (2014). Regimes of Value in Mexican Household Financial Practices. Current Anthropology, 55(S9), S30–S39. https://doi.org/10.1086/676665

[1] CNBV’s Financial Inclusion Database from June 2019 can be accessed here: https://www.gob.mx/cnbv/acciones-y-programas/bases-de-datos-de-inclusion-financiera

Rights & Permissions

You may use and disseminate CGD’s publications under these conditions.