Recommended

POLICY PAPERS

Blog Post

Historically, social assistance payments were often distributed in cash at designated payment points—government offices, community meetings, or schools. More recently, payments have increasingly been distributed digitally, through bank accounts or mobile wallets. As well as increasing flexibility and convenience for beneficiaries, advocates for this process argue that two development spillovers are possible. First, that this can stimulate financial inclusion and use among poor recipients. Second, that paying stipends digitally can empower female recipients by increasing their agency over the use of funds. Can digital payments live up to such promises? To understand more, we conducted surveys of beneficiaries of one of the largest programs directed to women, Bangladesh’s Primary Education Stipend Program (PESP), which reaches some 10 million mothers and 13 million children.

PESP originally paid stipends to mothers in cash at schools, but in 2017 it shifted to making payments through mobile wallets provided by SureCash, a new digital payments company. In 2019 payments were changed again to another provider, Nagad, a brand-new joint venture between investors and the Bangladesh Post Office. The most established mobile wallet provider, bKash, was not used for this transfer. An early study we conducted in 2019 had suggested that most mothers indeed welcomed the new payments arrangements relative to cash at schools, but it was not able to go more deeply into development spillovers. So, in 2021 we conducted a follow up study in partnership with Microsave Consulting (MSC). MSC administered a survey to 1,215 mothers across Bangladesh, including 979 who had previously, or were currently, benefiting from mobile money payments from PESP, and a control group of 236 who had never received digital payments under the program.

We hoped to assess if beneficiaries could:

- Access the tools required, whether a SIM card, phone, agent or ID card?

- Adapt to successfully navigate the payment process?

- Adopt new digital facilities, such as mobile financial services, beyond cashing-out their grants?

- Did the mothers feel that the payments modality had increased their agency and autonomy?

What did we find?

Much as in our previous study, the PESP recipients we surveyed reported that they had reliable access to the necessary resources and were adapting well to digital payments under the program. Roughly 95 had their own cell phone, and respondents consistently cited the proximity to agents and ease of cashing-out as a strength of the payment system. Moreover, about 93 percent who had received cash payments preferred digital delivery, a higher percentage than in the earlier study (80 percent).

Almost three-quarters of mothers receiving transfers digitally felt a greater sense of control over the use of the PESP funds than if they had been paid in cash. These included many mothers who were accompanied by other (usually male) household members when they cashed out, and many who did not feel comfortable using digital tools themselves. At least in this area, the new payment mechanism appears to increase the agency of women, and more so if they receive the payment on their own mobile phone.

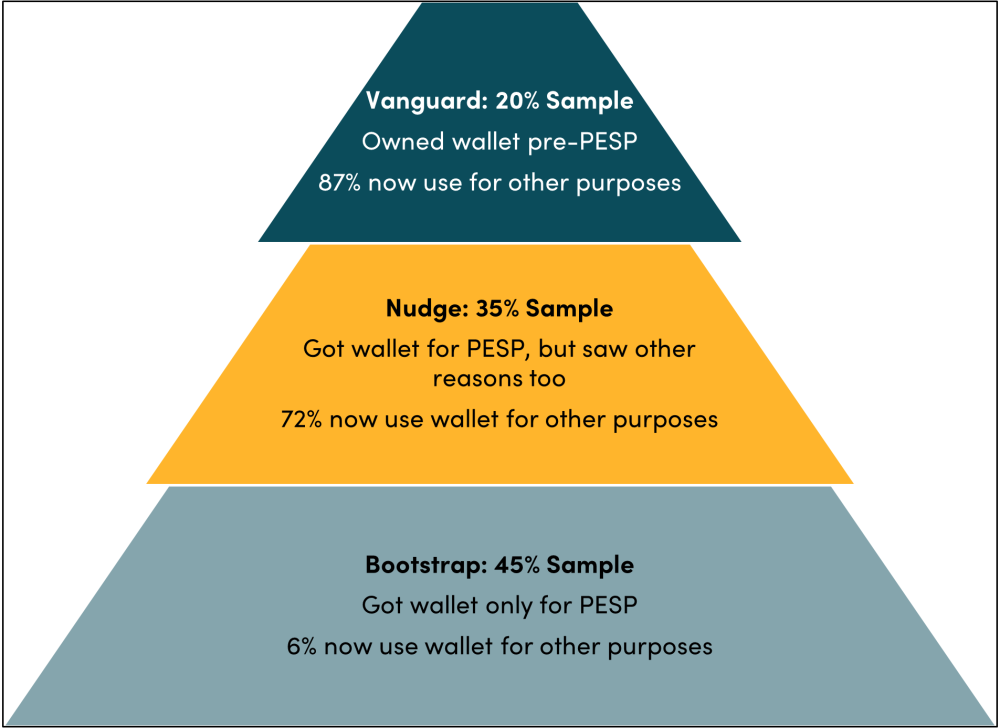

On adoption of digital payments, however, the study revealed more nuanced findings, with outcomes greatly influenced by the digital capacity and economic standing of recipients. Almost all mothers who owned a mobile wallet before benefiting from PESP (the “Vanguard” group) reported using it for other purposes. Of mothers who did not own a mobile wallet prior to PESP, almost half said that they had been considering getting a wallet for other uses (the “Nudge” group). Among this group, nearly three-quarters reported using their wallets for purposes other than cashing out stipends. Few of the remaining recipients, who said that they had opened wallets only to receive PESP stipends (the “Bootstrap” group) reported using them for anything beyond cashing out.

Further analysis showed that these groups are distinctive, with a clear statistical progression in their levels of education, quality of housing, location in an urban or semi-urban area, ownership of a bank account and a smartphone, and ability to read SMS. Overall, 28 percent of all PESP beneficiaries had transitioned from not having wallets before receiving the digital transfers to using their mobile wallets for purposes beyond cashing out. The effect was greatest, however, among those with more favorable socioeconomic indicators, who had been ”nudged” by PESP into getting mobile wallets. Digital capacity and literacy remain serious constraints, with only 28 percent being able to read and 18 percent able to write SMS in Bangla.

This before-and-after comparison does not, however, take into account the fact that Bangladesh has been making notable strides towards digital payments beyond PESP. To understand more, we can compare our PESP sample to the control. Of this group, 34 percent held neither bank accounts nor mobile wallets, suggesting that many PESP beneficiaries might not have held any financial account in the absence of the digital transfer. But in addition, 13 percent of the control were financially included only because they held a wallet with Nagad, the new and rapidly growing provider, promoted by its role in PESP but with a customer base that had expanded far beyond beneficiaries. The strategy may therefore have had a positive general impact on market competition for mobile financial services and inclusion, at least in the short and medium run.

Where does this leave us?

Many countries can learn from Bangladesh, including the various ways in which it has followed a beneficiary-centric approach. Overall, the digital payment system for PESP appears to be working well, and has had positive spillovers onto financial inclusion and (at least in this area) women’s empowerment. The strategy may also have increased competition in financial markets with wider benefits. But the study also shows that moving on from digital transfers towards universal adoption of digital payments and services is a slower process, heavily conditioned by the capacity of beneficiaries to use digital systems.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.

Image credit for social media/web: Adobe Stock