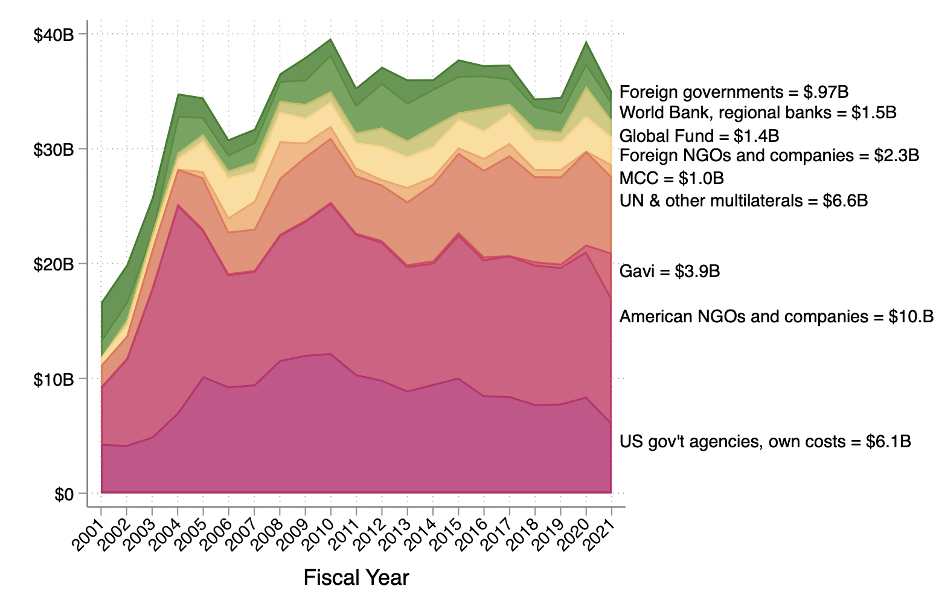

Part 1: If USAID wants to meet its targets of working with local partners, it needs to embrace the biggest ones: governments.

Foreigners don’t receive much of America’s $35 billion annual foreign aid budget, at least not directly. Less than ten percent goes to local charities, companies, or governments in developing countries. Instead, big American aid contracts tend to go to big American companies and non-governmental organizations (NGOs). The biggest beneficiaries—known in Washington as “beltway bandits”—each win hundreds of millions of dollars in federal awards every year.

While there are important cases where relying on American intermediaries makes good sense—for the purchase of large volumes of HIV/AIDS drugs for low-income countries, for instance—nobody really believes it’s a good idea to rely almost exclusively on American firms to do rural development in Kenya or public health campaigns in Bangladesh. The status quo doesn’t reflect any high-minded theory about what makes good aid. It’s just an intractable juggernaut of federal procurement rules and vested interests.

Obama tried to reform the system. USAID’s biggest implementing partners fought back and won. The Trump administration tried again, with its “journey to self-reliance,” but had no discernible impact on the actual dollars going to different destinations (see below). The Biden administration is trying a third time. But it needs to think bigger.

Figure 1. All U.S. non-military foreign assistance by channel

Source: ForeignAssistance.gov

A year ago in one of her first major policy speeches, Biden’s USAID administrator, Samantha Power, pledged that “moving forward, we are going to provide at least a quarter of all our funds directly to local partners within the course of the next four years.” She also announced a “50 percent local voices target,” whose metrics are a bit squishier, but focuses on local partners choosing and designing projects rather than just implementing them.

This is a great agenda. Local ownership is obviously not the only thing that matters in development. We also care about stuff like cost effectiveness. And critics of the localization agenda will, no doubt, make sure USAID remains highly attuned to any possible tradeoffs between localization and other goals. I’ll try to bring some data to that debate in future posts. But let’s just assume for now that all else equal, we’d rather have Tanzanians leading Tanzania’s development.

The question is how to get there. So far much of the public discussion has focused on making more grants to foreign charities and giving more contracts to foreign firms. That’s a great start, but it’s unlikely to deliver on the Biden administration's goals for two reasons:

-

Staff shortages. USAID lacks the staff required to oversee tens of thousands of small grants and contracts to local NGOs and firms.

-

A lack of ambition. Localization should imply more than hiring local contractors to implement American projects – replacing Deloitte, USA with Deloitte, Tanzania. The idea was supposed to be to give local communities control and discretion over how development funds are used.

Luckily, there’s a better way. Both these problems could be helped by focusing more on government-to-government aid, and working with multilateral institutions like the World Bank and regional development banks.

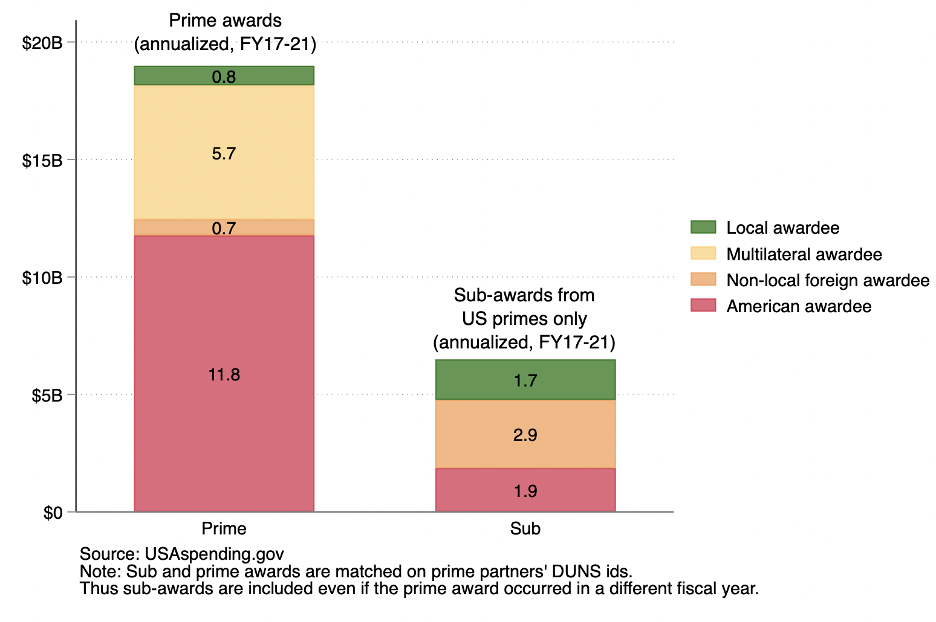

It’s just not true that USAID’s American implementing partners pass on most of their money to local organizations via subawards

Before we dive into the more interesting numbers, there is one distraction we need to put to rest. Whenever localization comes up and USAID starts talking about giving more grants or contracts to local organizations, the big American implementers respond with some version of “but we already give tons of money to local organizations as sub-awardees. And honestly, you need us to hold their hands if you’re ever going to work with them.”

Alas, there is no data to back up this assertion. (There are rumors that partners fail to report some subawards, so this picture could be incomplete. But it seems unlikely that USAID’s American implementers are giving billions of dollars to local companies and NGOs and failing to claim credit for that.)

Figure 2. How much do USAID’s American partners pass on to local organizations as sub-awardees?

Based on the data we have from the U.S. government’s procurement spending portal, USAspending.gov, Figure 2 shows the total amount of money awarded as grants or contracts by USAID per annum (FY2017-2021) broken down by who gets the prime ward. And then the second set of bars shows how much American organizations pass along in sub-awards to various types of organizations.

The short answer is that about $1.7 billion went from American primes to local sub-awardees in FY2021. That’s significant—roughly twice as much as local orgs receive in prime awards. But it doesn’t change the overall picture that the lion’s share of tenders go to American firms. Not to mention that as “subs,” local organizations may have limited agency to scope or shape the work--or feel beholden to their prime partner.

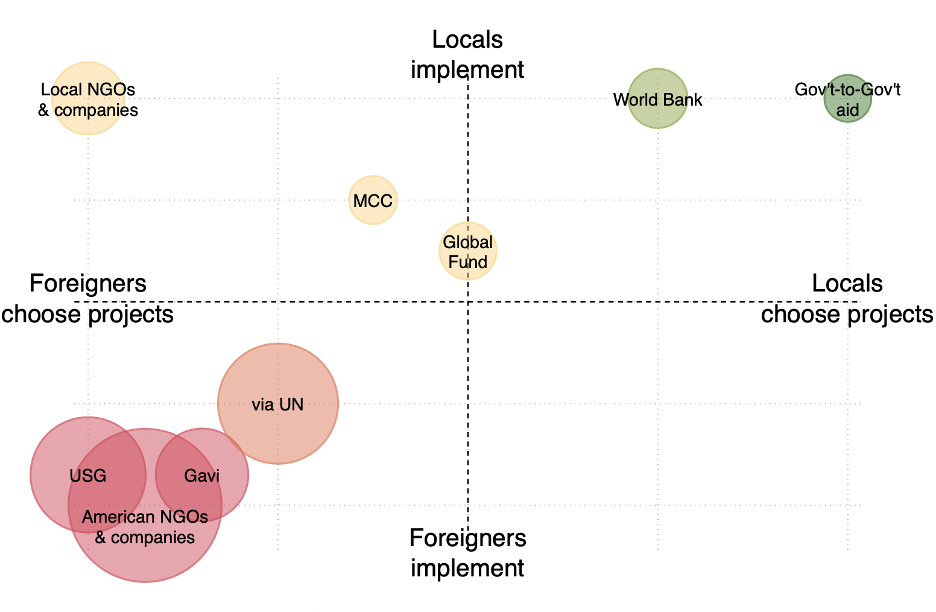

Working with governments and (some) multilaterals gives local actors more agency than USAID can give to local firms and NGOs

The first policy documents emerging from USAID’s push toward localization raise a host of nuanced considerations the agency must weigh. But for simplicity, let’s focus just on the two main dimensions in Administrator Power’s original pledge a year ago:

-

Implementation. Investing in local institutions.

-

Design. Giving locals a choice and a role in project design.

For illustrative purposes, in Figure 3 I tried to score the major channels of US foreign aid along these dimensions: how much control do ‘locals’ have over the design and the execution, respectively? These scores are super subjective. People can reasonably quibble about specific rankings—e.g., where exactly do the Global Fund or MCC belong there in the middle—but I hope a few core points are uncontroversial:

-

If USAID contracts an American company to dig borehole wells in Tanzanian villages, that scores pretty low on both dimensions of localization (red bubbles at bottom left).

-

If USAID contracts a Tanzanian company to dig the same holes (yellow bubble, upper left), that scores better on the vertical “locals implement” axis, but no better on the horizontal “locals choose projects” axis.

-

On the other hand, if the U.S. writes a check to the government of Tanzania, to spend in a sector of Tanzania’s choosing, on projects to be administered by the Tanzanian government, that scores pretty high on both dimensions (green bubble, top right).

Figure 3. Conceptual scoring US foreign aid channels (see explanation below)

NB: The size of the bubbles is proportional to the total U.S. foreign assistance per aid channel in fiscal year 2021, based on data from foreignassistance.gov.

A lot of the energy in the localization discussion at USAID is about converting red bubbles into yellow bubbles. In that scenario, USAID’s basic modus operandi of contracting people to do development projects will be unchanged, but more local organizations will win those tenders. But there is a good case that it would be better, and also bureaucratically easier, to convert the red bubbles into green bubbles.

Thinking bigger (governments, multilaterals) also requires less paperwork

If you talk to current or former USAID people about the drive for localization, the bottleneck that always comes up is staff bandwidth to process thousands and thousands of awards to small, local organizations.

USAID is understaffed by design. In the 1990s congressional Republicans led by then Senator Jesse Helms attacked foreign aid as throwing “American taxpayers' money…down foreign ratholes to countries that constantly oppose us in the United Nations,” and Bill Clinton agreed to slash the agency’s headcount as a show of government efficiency. (John Norris’ history of USAID has a fascinating account of this saga.) Bush II boosted aid budgets with HIV/AIDS relief for Africa and Iraqi “reconstruction,” but he carefully avoided letting USAID grow in size.

Unfortunately, grants and contracts to local organizations usually need to be small. There aren’t a lot of companies in Tanzania that can absorb a $30m grant, much less the $1 billion awards USAID’s biggest American contractors get.

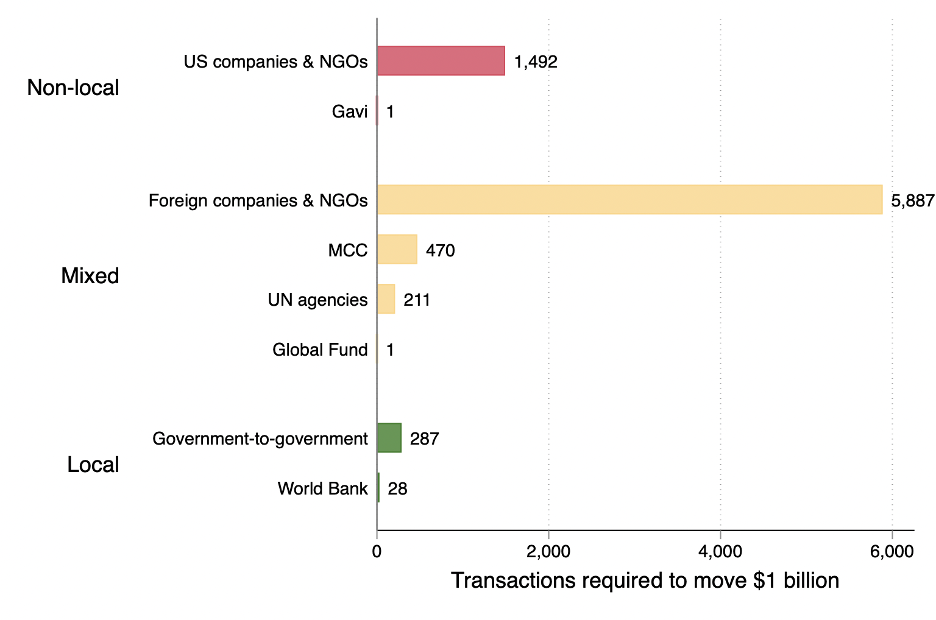

So if USAID is serious about localization it needs to look for ways to move large amounts of money with minimal transactions. As a crude guide, Figure 4 shows how many transactions it takes to move a hypothetical $1 billion in foreign aid based on data from the US foreign assistance dashboard.

Figure 4. How many transactions does it take for the U.S. government to move $1 billion in foreign aid via…

The answer is about 1,500 transactions if you’re working with American firms, and over 5,000 smaller transactions if you work with local orgs.

But again, there are other options. The U.S. writes single checks for more than $1 billion to the Global Fund to Fight Tuberculosis, AIDS, and Malaria, which doesn’t perform too badly in terms of localization. And it only takes 28 transactions to give a billion dollars to the World Bank, which performs even better—or best of all, 287 transactions to give the money straight to developing-country governments.

If USAID is serious about empowering local partners, it needs to think bigger. Go beyond contracting small local organizations as agents to implement projects designed in Washington. Engage with institutions that give local actors real discretion, and can responsibly manage big chunks of American aid—i.e., governments and multilateral organizations. That’s not only a more meaningful concept of “localization,” it’s a lot more bureaucratically realistic.

Thanks to Erin Collinson, Amanda Glassman, Charles Kenny for helpful comments on a first draft.

Postscript 1: Data and code

Download Stata code to produce all graphs in this post.

Data on prime and sub-awards is available from USAspending.gov.

Data on U.S. foreign assistance from all agencies by channel is available at ForeignAssistance.gov.

Postscript 2: Justification for the localization scores in Figure 3

| Local institutions control program design and have discretion on use of funds? | Local institutions execute budget and implement projects? | |

|---|---|---|

| The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria | 3 – Restricted to health, and to specific disease silos. But in principle, recipient governments, civil society, etc. get to shape program design via Country Coordinating Mechanisms. | 3.5 – Program implementation varies by country, and may rely on recipient-country governments, local firms and NGOs, or foreign contractors.. |

| U.S. government agencies, own costs | 1 – No local control. | 1 – No local role in implementation. |

| Gavi | 1 – Gavi provides a set menu of vaccines. There’s little scope for beneficiary control or discretion. | 1 – Vaccines are largely delivered in-kind, given cost efficiencies of bulk procurement. |

| The World Bank, regional development banks (IADB, ADB, AfDB) | 4 – In theory, recipients must sign up to take out a World Bank loan for a specific purpose. In practice, of course, World Bank staff also shape projects. | 5 – In the case of IDA and IBRD, which constitute the bulk of World Bank aid, all money flows to the Treasury of the recipient country, to be executed by the recipient government. The IFC and MIGA support private sector projects including non-LMIC firms. |

| Foreign governments | 5 – Even when earmarked for a specific purpose, aid to national treasuries tends to be highly fungible, giving governments considerable discretion over its precise use. | 5 – By definition, government-to-government aid relies on a large degree of local implementation. |

| USAID grants/contracts to US organizations | 1 – Sectors, topics, and program design are stipulated by USAID informed by Congressional earmarks. | 1 – Notably, a rather small share of prime awards to US organizations ever reach local organizations even as sub-grantees or contractors. |

| USAID grants/contracts to local organizations | 1 – Sectors, topics, and program design are stipulated by USAID informed by Congressional earmarks. | 5 – By definition, local partners implement. |

| Millennium Challenge Corporation | 2.5 – MCC doles out money via “compacts,” which are based on MCC’s own economic analysis, but negotiated with recipient governments. | 4 – Projects are executed by a unique entity called the Millennium Challenge Account created in the recipient country, generally staffed and led by recipient-country nationals, but designed and governed according to specifications laid out by the U.S. government. |

| UN agencies and other multilaterals | 2 – The bulk of US spending in this category goes to WFP and UNICEF. For the most part, these agencies decide when, where, and what to spend on, albeit in consultation with local partners. | 2 – Most WFP or UNICEF funds are spent on either the transfer of commodities or technical assistance, leaving little scope for local implementation. |

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.