Recommended

As the global trade powerhouses lurch towards protectionism, CGD’s Commitment to Development Index, released today, reveals which advanced economies have trade policies that support—or fail to support—lower-income countries.

The Netherlands comes out on top, with overall trade policies that do the most for development, while Australia and New Zealand have the lowest tariffs against low-income countries, with the EU close behind. But some countries can do much more to remove tariffs against their poorest trade partners, and almost all countries have room for improvement.

Here we look at the results, and at how countries can encourage development in the face of a global trade slowdown.

Trade matters to development

Almost no country has developed successfully without increasing trade, and exports as share of the global economy have risen steeply alongside dramatic falls in the number and percentage of the extreme poor. China lifted 800 million people out of extreme poverty in the last quarter century with little or no aid, thanks largely to market reforms, succession to the WTO, and trade growth.

The global trading environment is dominated by advanced economies, with the G7 alone accounting for over a third of global trade. And, alongside the rules of the WTO, domestic policies are also important. The CDI, which ranks 27 of the world’s richest countries across seven areas on how well their policies promote global prosperity, considers four elements of trade policy: tariffs, agricultural subsidies, restrictions on trade in services, and logistic costs.

New approach to tariffs in the CDI

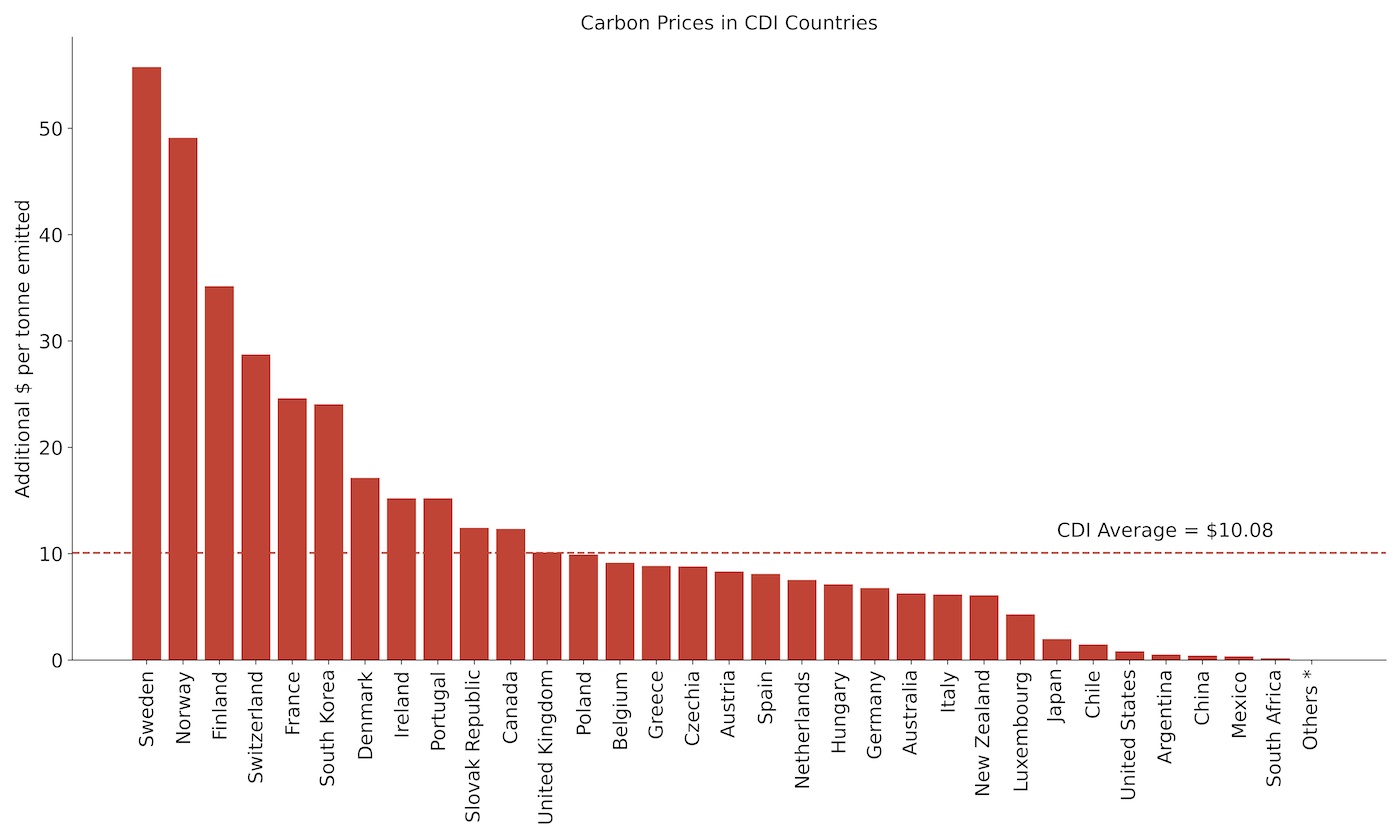

The CDI has always included tariffs because they are often in sectors that matter most to development, like agriculture and textiles. But this year, we’ve introduce a new ranking method which penalises countries more for tariffs against lower-income countries.

In particular, for each of the 27 CDI countries, we look at the average applied tariff for every bilateral trade relationship, with a higher weight for those levied against lower-income partners. Using the average applied tariff across products might seem like a major simplification, but it correlates strongly with more sophisticated measures that give a higher weight to tariffs in certain (developmentally relevant) sectors. Importantly, it also avoids the problems with “trade-weighted” tariffs, which tend to put very little weight on the highest and most damaging tariffs.

To weight tariffs, we use the logarithm of the trade partner’s per capita gross domestic product. The logarithm gives extra emphasis to tariff improvements at the lower-income end of the spectrum.

In short, our new approach “poverty-weights” tariffs.

The Netherlands leads overall on trade

In the overall trade results in the CDI, the Netherlands’ trade policies do the most for development, with low impediments on both services and logistics. The Netherlands also enjoys the EU’s tariff regime, which scores very well. On agricultural subsidies, its EU subsidies are lower than most, leading by example in its traditional advocacy for reform.

The Netherlands' Trade Scores

And on tariffs, Australia, New Zealand, and the EU lead

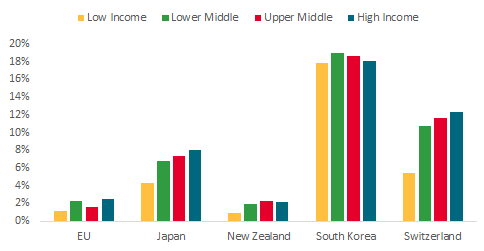

Australia and New Zealand have the lowest tariffs, both before and after income-weighting. (New Zealand’s tariff profile is shown in the graph below, and Australia’s is very similar.) Contrast this with Switzerland, which has high but progressive tariffs, and with South Korea, which has high but regressive ones—its average tariff against the income categories of its trading partners falls as the category rises. The EU has the third-best ranking on trade for development tariffs, and a clearly progressive pattern.

The major beneficiary of the CDI’s new approach to tariffs is Japan—its tariffs are high but progressive, and the new method lifted its position in the overall trade scoring by 10 places to 15th.

Tariffs and Trading Partner Income

How countries should respond to the impending trade war

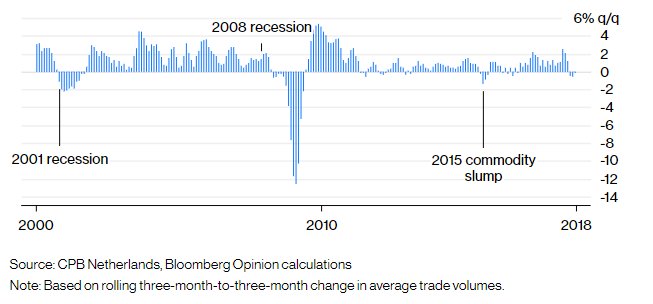

Whilst stock markets remain bullish about company prospects, the impending trade war is now visible in trade volumes, and prior episodes of falling trade have often coincided with recession.

Rolling Three-Month Trade Volumes Are Already in Decline, a Rare Situation in Recent Decades

As countries plot their retaliation, they should consider diplomacy and make every effort to sustain free global trade before succumbing to the pressure to respond with tit-for-tat protections. They should defend the global rules that are designed to limit unfair trade. But they should also look to deepen links with new trade partners in the developing world and address all the dimensions of trade, from logistics to agricultural subsidies and services. This would offset trade impacts elsewhere as well as help to diversify trade risk and build new economic ties.

Trade is arguably the most important pathway to development. Rich countries should defend the rules-based trade system that allowed them to thrive and prosper and use their trade policies to support growth in poorer countries.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.