Recommended

Corrective taxes on harmful products—health taxes—are a cost-effective way to save lives and generate additional tax revenue.[1] Our previous work shows that corrective tax revenue from alcohol, tobacco, and sugar-sweetened beverages remains well below the health-related costs from consumption (externalities and internalities).[2] We survey measures taken in IMF lending to 93 countries during 2017–2021. We show that health tax measures during COVID-19 have diminished in number and strength because the international community has mobilized additional, largely unconditional financing to fill budgetary gaps and because countries sought to cushion consumers’ reduced spending power by delaying new or increased taxes. But, as policymakers look to medium-term budget consolidation, international financial organizations (IFIs), especially the IMF, have an important role to play in ensuring health taxes move forward more rapidly. We reiterate an action agenda on health taxes for the IMF in coordination with other international agencies.

Consumption of harmful products during COVID-19

COVID-19 can affect harmful products consumption in different ways: lockdowns may have reduced the availability of alcohol and tobacco and/or discouraged consumption of harmful products for health reasons; in the other direction increased stress may have raised tobacco and alcohol consumption while increased leisure time could encourage greater consumption of sugary beverages and junk foods. The evidence so far suggests tobacco consumption increased, perhaps as remote working offers more opportunities for smoking than smoke-free offices, while alcohol decreased at least during lockdowns: in the United States self-reported alcohol consumption fell substantially in 2020,[3] while 2020 cigarette consumption rose for the first time in 20 years,[4]a similar pattern was observed in France for alcohol and tobacco during lockdown in 2020,[5]and in New Zealand for tobacco.[6] However, in China surveys showed that more individuals quit smoking than started after the COVID outbreak.[7] Multinational company reports suggest that the global COVID-19 impact on tobacco sales was modest and for alcohol and SSBs it was temporary: revenues of the big-four tobacco companies rose by 2.8 percent in the 12 months after the COVID-19 outbreak, while revenues of large drinks and snacks companies, e.g. Diageo, Pepsico, rebounded in 2021 after a 2020 lockdown decline.[8]

Trends in corrective health taxes in IMF programs

There is no centralized collection of data on health tax implementation,[9] so we use information on policy commitments from 93 countries with IMF financial support as a proxy for health tax measures taken during 2017–2021.[10] IMF program countries are representative of a broader group of mainly low- and middle-income countries containing countries with high alcohol or tobacco consumption (e.g. Ukraine, Pakistan), high SSB consumption (Mexico, Chile) as well as countries with relatively low harmful products consumption (e.g. low-income West African countries).

We identify program policy commitments on corrective health taxes on tobacco, alcoholic drinks, and sugar-sweetened beverages by searching for keywords “excise,” “tobacco,” “cigarettes,” “alcohol,” “beer,” “wine,” “spirits,” and “sugar” in published Staff Reports for IMF arrangements (SCF, ECF, SBA, EFF, PLL, FCL[11]) and staff-monitored programs during 2017-2021 as well as emergency financing (RCF and RFI)[12] building on our previous work in this area.[13]

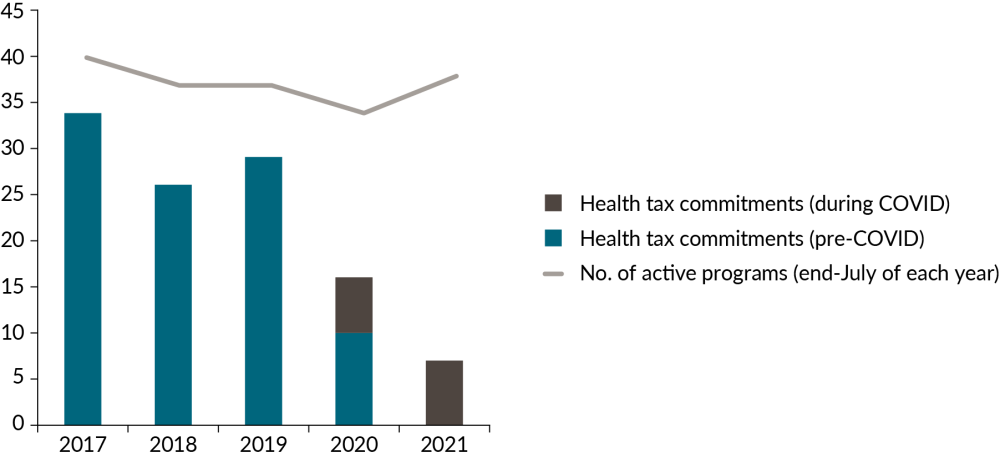

Despite drops in government revenues and the role of tobacco, alcohol, and other factors in increasing risks of severe COVID-19, we find that the frequency of higher corrective health taxes on tobacco, alcohol, and unhealthy food & drink has diminished during the COVID-19 pandemic in a large group of developing countries with IMF-supported programs. Corrective health tax commitments in countries with IMF-supported programs declined from around 30 commitments per year pre-covid-19 during 2017-2019 to 6 commitments in 2020 (April-December) and 7 commitments in 2021 (Figure 1). In addition, of the 80 countries that received IMF emergency financing during COVID-19, only three loan requests made any reference to health taxes.

Figure 1. Corrective health tax commitments in IMF programs, 2017–2021 (count)

Source: Text search of IMF Staff Reports and IMF Financial Reports.

Note: IMF programs are SCF, ECF, SMP, SBA, EFF, PLL, and FCL. Does not include emergency financing under RCF and RFI.

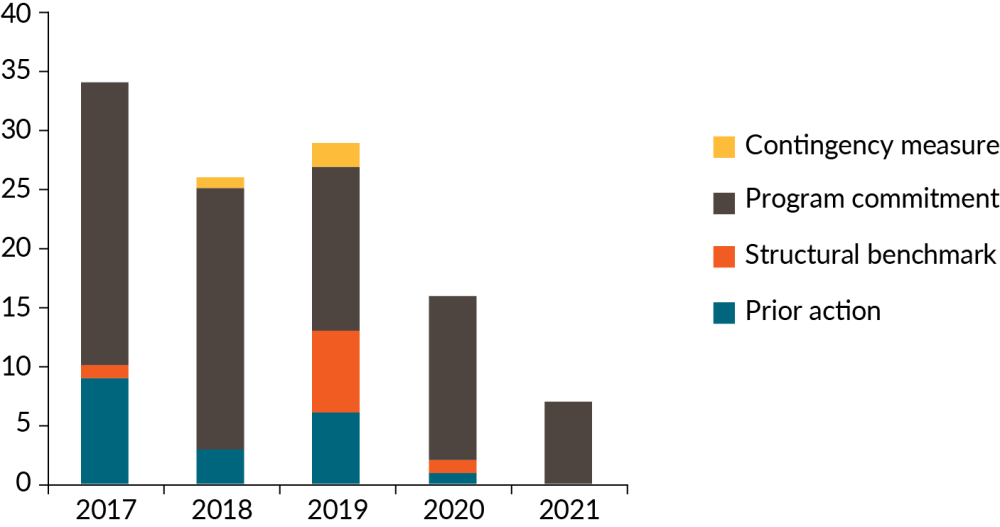

We also measure the strength of policy commitments under IMF arrangements: (i) the strongest commitment is a prior action, or a part of a prior action, that countries agree to implement prior to the approval of a program request or program review for release of IMF financing; (ii) the second-strongest commitment is a structural benchmark that sets a time-bound date for implementation of the action with country authorities responsible for reporting implementation (or not, as the case may be); and, (iii) third, is a statement of intent expressed in the program Memorandum of Economic and Financial Policies or in the accompanying staff report; or, (iv) fourth-strongest as a contingency measure.

We find that the strength of health tax commitments has diminished during the COVID-19 pandemic with one prior action and no structural benchmarks during April 2020 to November 2021 (Figure 2).

Looking in more detail at the COVID-19 health tax measures in IMF lending only 4 of 18 total measures have estimated revenue yields ranging from 0.13 to 0.20 percent of GDP (See Appendix Table 1).

Of the 13 measures in regular program financing; one is a part of a prior action—implementation in Ukraine of a previously announced increase of tobacco taxes as part of a revenue package and harmonizing taxation of heated and traditional tobacco products; of the other measures, 5 increase tobacco excises (Burkina Faso, Egypt, Gambia, Sudan, and Ukraine (additional to the prior action), one increases sugar taxes (Sudan), 4 operationalize an excise stamp duty regime for alcohol and tobacco (Liberia and Sierra Leone) and 2 others consider reforms to alcohol and tobacco excises in line with regional guidelines (Mali).

Of the 5 measures in emergency financing, 4 are temporary or tentative in nature (for alcohol and tobacco taxes in Bahamas and Lesotho) and at least 2 of these were not implemented (Bahamas). The remaining measure resumes a stepwise increase of tobacco taxes that was initiated in 2017 (Tunisia).

Figure 2. Health taxes commitments in IMF programs by type, 2017–21 (count of actions)

Source: Text search of IMF staff reports.

Diminished appetite for health taxes?

Why has the appetite for corrective taxes diminished during COVID-19 in IMF programs, despite evidence that non-communicable diseases associated with tobacco and alcohol use, and unhealthy diets increase the risk of severe illness from COVID-19,[14] and corrective taxes could mobilize additional revenues including to support hard-pressed health sectors?

At least four factors are relevant to answer this question:

First, it is not because the incidence of IMF-supported programs (excluding emergency support) has diminished. The number of active programs remained broadly stable during the 2017-21 period (34-40 countries with active programs at mid-year as shown in Figure 1).

Second, the IMF emergency financial support to 80 member countries during COVID-19[15] has no ex-post conditionality as it is designed to meet urgent balance of payments or budgetary needs providing a country is taking steps to address its economic difficulties. Given the nature of emergency financing, the emphasis is on closing financing gaps rapidly rather than supporting medium-term revenue mobilization, including through health taxes.

Third, the allocation of Special Drawing Rights equivalent to about US$ 650 billion to IMF members in August 2021, also without conditions attached, may also have lessened the need to take revenue measures, including corrective health tax increases, at least temporarily.

Fourth, the pandemic is viewed to have worsened income inequality with job and income losses likely to have hit lower-skilled and uneducated workers the hardest.[16] Accordingly, policymakers may view higher corrective taxes weighing on already hard-pressed low-income groups in the short term, for whom the affordability of these products has already decreased due to income losses as shown in recent work on tobacco affordability around the world.[17]

Nonetheless, those countries that implemented health taxes during COVID-19 with non-negligible revenue increases, such as Egypt and Ukraine, were able to mitigate the fall in total tax revenues and decrease health-related expenditures in the long run assuming permanent reductions in consumption levels.

The road ahead for corrective health taxes

While progress in IMF program support to health taxes has diminished during the pandemic, there are indications that policymakers are readying for more ambitious corrective taxes and other measures to improve population health and support revenues as or when COVID-related disruption diminishes.

In some countries “post-pandemic” health tax measures are taking shape. For example, from 2023, Kazakhstan will introduce an excise tax on sugar-sweetened beverages within the framework of the Healthy Nation project prepared by the Ministry of Health with excises starting at 20 percent and rising to 45 percent over time.[18] In New Zealand, which already has amongst the highest levels of tobacco taxes in the world, legislation is planned in 2022 to progressively ban the sale of tobacco products from 2027 following other efforts to reduce points of sale and lower tobacco nicotine levels.[19]

Yet overall health taxes remain low including in countries with high non-communicable disease burdens arising from harmful product consumption. During the pandemic unhealthy products have in some cases become more affordable over time. There is more to to be done, and quickly to save lives and money.

Next steps for the IMF and health taxes

International financial institutions, including the IMF, World Bank, and multilateral development banks as well as the World Health Organization, can play an important role in helping countries strengthen their health taxes as COVID-19 wanes through policy-based lending, surveillance, and technical assistance.

At the IMF some progress was made on health tax policies during COVID-19. The IMF published a note on “How to Apply Excise Taxes to Fight Obesity” in December 2021 which makes a cautious case to tax sugar-sweetened beverages in both low-income and advanced economies.[20]

The IMF also has provided guidance to “Exploit excises on alcohol, tobacco, and unhealthy foods” as a part of tax policies for inclusive growth “after the pandemic”.[21] In order to realize this goal, recommendations that we set out in an action agenda for IFIs and health taxes remain relevant today.

Specifically for the IMF the key actions we propose are:

-

acknowledge the macro-criticality of health taxes on tobacco, alcoholic and sugary beverages in many countries, in light of the potential for increased revenue alongside reduced healthcare costs, for example in the context of a policy paper approved by the IMF Executive Board;[22]

-

expand use of health taxes in financial programs given short-term revenue potential and corrective efficiency (in reducing externalities);

-

expand and publish technical assistance on health taxes, while also using World Bank and WHO expertise to help design health tax reforms and assess their impact on health, poverty, and society, systematizing lessons learned that can be shared across countries;

-

use medium-term revenue strategies as a vehicle for promoting health taxes where countries express an interest. This could also include neglected areas such as tax expenditures (tax breaks) for tobacco and alcohol producers and duty-free sales.

-

realize the opportunity for the IMF, World Bank, United Nations, and the OECD to work together on health tax issues in the Platform for Collaboration on Tax (PCT)[23] to jointly promote health taxes in their work and to develop PCT guidance on health tax implementation bringing together complementary work in each of the four institutions.

[1] Task Force on Fiscal Policy for Health, Health Taxes to Save Lives: Employing Effective Excise Taxes on Tobacco, Alcohol, and Sugary Beverages (New York: Bloomberg Philanthropies, 2019).

[2] Chris Lane and Vinayak Bhardwaj, Meeting the Global Health Challenge to Reduce Death and Disability from Alcohol, Tobacco, and Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Consumption with Corrective Taxes, CGD Policy Paper 240 (Washington, DC: Center for Global Development, 2021).

[3] Adult respondents reporting alcohol consumption fell from 65 percent in 2018 to 60 percent in 2020, https://news.gallup.com/poll/353858/alcohol-consumption-low-end-recent-readings.aspx.

[4] See Federal Trade Commission, Cigarette Report for 2020 (2021), https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/reports/federal-trade-commission-cigarette-report-2020-smokeless-tobacco-report-2020/p114508fy20cigarettereport.pdf.

[5] Romain Guignard et al., Changes in smoking and alcohol consumption during COVID-19-related lockdown: a cross-sectional study in France, European Journal of Public Health 31, no. 5 (October 26, 2021): 1076-1083, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckab054.

[6] Philip Gendall et al., Changes in Tobacco Use During the 2020 COVID-19 Lockdown in New Zealand, Nicotine & Tobacco Research 23, no. 5 (May 4, 2021): 866-871, https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntaa257.

[7]Haiyang Yang and Jingjing Ma, How the COVID-19 pandemic impacts tobacco addiction: Changes in smoking behavior and associations with well-being, Addictive Behaviors 119 (August 2021): 106917, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2021.106917.

[8] Data on tobacco company revenues from Ford Equity Research accessed at www.fidelity.com. Revenues of Japan Tobacco, Philip Morris International, British American Tobacco, and Imperial Tobacco increased from US$ 123.3 billion in the year to March 2020 to US$ 126.8 billion in the following 12 months.

[9] The Tobacconomics Cigarette Tax Scorecard provides information on tax share and structure on cigarettes for most countries based on data from a World Health Organization biannual survey. However, the 2021 scorecard covers the period 2018-2020 which covers both COVID-19 and pre-COVID-19 time periods.

[10] Of the 93 countries receiving IMF financial support during COVID-19 through December 2021, 41 received emergency financing only, 39 received emergency and regular program financing or precautionary support, 13 received only regular program financing or precautionary support.

[11] IMF arrangements or programs are stand-by credit facility (SCF), extended credit facility (ECF), stand-by arrangement (SBA), extended fund facility (EFF), precautionary and liquidity line (PLL), flexible credit line (FCL).

[12]Emergency financing comprises of the rapid credit facility (RCF) and rapid financing instrument (RFI).

[13] Chris Lane, Amanda Glassman, and Eleni Smitham, Using Health Taxes to Support Revenue: An Action Agenda for the IMF and World Bank, CGD Policy Paper 203 (Washington, DC: Center for Global Development, 2021).

[14] Zlatko Nikoloski et al., Covid-19 and non-communicable diseases: evidence from a systematic literature review, BMC Public Health 21, no. 1068 (2021): 1-9, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11116-w.

[15] Emergency support through the Rapid Financing Instrument and Rapid Credit Facility with temporarily higher levels of support available than prior to COVID-19.

[16] Francisco H. G. Ferreira, Inequality in the Time of COVID-19, Finance & Development (June 2021): 20-23, https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2021/06/inequality-and-covid-19-ferreira.htm.

[17]Frank J. Chaloupka et al., Tobacconomics Cigarette Tax Scorecard (2nd Edition) (Chicago: University of Illinois Chicago, 2021).

[19] https://www.reuters.com/business/healthcare-pharmaceuticals/new-zealand-plans-lifetime-ban-cigarette-sales-stamp-out-smoking-2021-12-09/.

[20] Patrick Petit, Mario Mansour, and Philippe Wingender, How to Apply Excise Taxes to Fight Obesity (Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund, 2021).

[21] Ruud de Mooij, Ricardo Fenochietto, Shafik Hebous, Sébastien Leduc, and Carolina Osorio-Buitron, Tax Policy for Inclusive Growth after the Pandemic, IMF Fiscal Affairs Department Special Series on COVID-19 (Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund, 2020).

[22]The IMF has published a technical note on tobacco taxation: Patrick Petit and Janos Nagy, How to design and enforce tobacco excises?, IMF Fiscal Affairs Department How-To Note (Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund, 2016).

Rights & Permissions

You may use and disseminate CGD’s publications under these conditions.