Introduction

Policy debate over immigration has intensified amidst growing global refugee crises and a wave of nationalist electoral victories. Often that debate focuses on a narrow question. Policymakers and voters reasonably want to know what the effects of immigration are, to help them decide how much immigration there should be.

But many such debates have gone in fruitless circles. The effects of immigration are highly contingent on where, when, how, and who. The effects of Afghan refugees in Canada and Bolivian nannies in Spain are not comparable; they depend utterly on their respective contexts and are shaped fundamentally by the details of how countries regulate that mobility.

No case study or academic paper can—ever—spell out what “the” effect of “immigration” is. Asking this question has as little use as asking whether “taxes” are inherently “good” or “bad.” The answer depends on what is taxed and what the revenue is spent on. Those choices make the policy harmful or beneficial. The same is true of migration.

But the world’s wealth of experience in regulating migration can still be a useful resource for setting better policy. We must ask a more fruitful question: how can different policy choices generate positive economic effects from immigration and avoid negative ones? Immigration is not inherently “good” or “bad.” Its effects depend on the context and the policy choices that shape it.

This is the key to understanding the mixed research findings on “the” impacts of immigration. Those impacts depend crucially on who comes, where they come from, the circumstances of their departure and arrival, what local communities they arrive in, what legal barriers and obligations they face, how natives’ own mobility is regulated, and many other decisions.

For example, immigration can negatively affect employment for some groups during some periods, especially natives with similar skills, experience, and job preferences as migrants (e.g., Hunt 1992, Gindling 2009). However, it can also create more and better employment—by encouraging natives to upgrade occupations (Foged and Peri 2016), raising labor force participation by natives (Cortes and Tessada 2011), and filling labor shortages to raise productivity (Clemens 2013). Similarly, immigration can either cost taxpayers money or deliver fiscal benefits (Ruist 2015; Collado et al. 2004), or lead to either increased or decreased service quality (Pedraja-Chaparro et al. 2015; Van Damme et al. 1998). These varying findings do not reflect confusion or inconsistency. They indicate that answers in different settings can be very different.

All these effects are blunted or accentuated by choices. They depend on how policymakers choose to regulate labor markets, benefits systems, and mobility itself. These choices either reap the rewards of immigration or create negative outcomes for the citizens of host countries, migrants, and migrants’ home countries. The answer to legitimate questions about the effects of migration is this: migration is what you make it.

The need for policies that facilitate positive outcomes from migration is only going to grow: over the next few decades, migration flows will likely increase substantially. Predictions indicate by 2040 the number of working-age people in low-income countries will expand by 91 percent, or over 330 million. In middle-income countries, the number is predicted to expand by 625 million.[1] Other predictions estimate an expansion of 800 million or more in sub-Saharan Africa alone (Hanson and Mcintosh 2016; Bertoli 2017). Even if migration rates remained constant, this population growth would imply a large absolute growth in migration.

But migration rates will probably rise: as low-income countries move to middle-income status, the pressure for their working-age populations to emigrate will grow because economic development generates new opportunities and motivations for migration (Clemens 2014). Certain interventions—such as those designed to create jobs, reduce violence, or interdict migrants—can play a role in reducing migration, but likely not enough to alter broader emigration trends (Clemens and Postel 2018; Clemens 2017a; Gathman 2008). And while the number of refugees is relatively small at 22.5 million, it could grow as conflicts and crises continue to emerge and burn longer (Bennett 2016). Likewise, a growing population will likely be displaced by the effects of climate change and state fragility.

With productive policies in place, an increase in migration can create new opportunities and benefits for host countries, origin countries, and migrants—a triple win. For migrants, moving to more developed countries creates the possibility for much higher incomes (Clemens and Postel 2017; Gibson and McKenzie 2014; Mergo 2016). For origin countries, emigrants’ higher incomes abroad can translate into higher incomes for their families at home through remittances, which can create other positive effects, such as improved nutrition and education outcomes (Carletto et al. 2011; Ambler et al. 2015).

Emigrants can also benefit their origin countries by transferring knowledge and technologies that diversify and benefit the economy, and the prospect of emigration can lead to greater investment in human capital (Clemens 2017b; Dustmann and Glitz 2011). And, regardless of whether the host country is developed or developing, the potential benefits of hosting migrants and refugees include (but are not limited to) higher incomes and employment rates for natives (Foged and Peri 2016; Akgunduz et al. 2018); net positive fiscal effects (Liebig and Mo 2013; OECD/ILO 2018); increased innovation (Moser et al. 2014; Kerr and Lincoln 2010); and more efficient, productive economies (Peri 2012).

With the wrong policies in place, these benefits may be lost and some of the fears that many have about immigration may be borne out. Fortunately, there is an evidence base to inform policymakers and leaders on realizing migration’s benefits.

In this paper, we harness evidence for the idea that policies shape the effects of migration by exploring case studies related to seven topics:

- If immigrants fill labor gaps, immigration creates jobs and raises incomes. Policies that allow immigrants to fill labor shortages create jobs, increase labor force participation rates, and increase incomes for natives. When policies restrict immigrants from filling shortages, economic opportunities are lost.

- Well-designed temporary migration programs fill critical labor needs, while also minimizing the risk of overstays. Temporary migration programs are an effective means to fill labor shortages. Whether they are accompanied by visa overstays and violations of workers’ rights depends on the incentives created by the program.

- Creating legal pathways for migration can reduce irregular migration. When policymakers create new legal channels for migration, irregular migration can decrease—when other key elements are in place. When these legal channels disappear, irregular migration may reappear.

- The fiscal impact of new immigrants is a policy choice, with potential contributions that go far beyond individual-level taxes paid. Immigrants can (and often do) contribute more in taxes than they receive in government services over time—especially if policies support and enable their successful integration into labor markets.

- Immigrants contribute to the economy as entrepreneurs, investors, and innovators—if they are allowed to. When policies lower barriers to business ownership, immigrants invest in their host economy, hire natives, and boost economic growth.

- Policy decisions in migrant origin and destination countries turn skilled migration into a drain or a gain. Skilled emigration creates a range of potential economic benefits for the migrants, the destination country, and the origin country—benefits that can be turned into real harms by policies designed for an immobile world. Skill partnerships between origins and destinations offer one path toward mutual benefit.

- With well-designed policies, immigrants can have a positive impact on the quality of service delivery. Immigration can either contribute to or harm service quality. Policy choices, such as creating integrated health systems for refugees and host communities, can determine the impact.

For each topic we provide examples of how some policy choices have created positive outcomes—and how others have created negative outcomes. Where evidence exists, we discuss how these choices have similar effects for economic migrants and refugees, in both developed and developing countries. Therefore, while our case studies sometimes focus on one type of migrant or host country income level, many of the policy lessons can be extended across migrants and refugees and income levels, with the caveat that the degree of potential benefit and cost is contingent on the context.

To be clear, this paper does not provide an exhaustive list of policies for shaping migration outcomes. We provide a few examples of how to do so, but there are many more options available, and future innovations will no doubt continue to expand these options. We also do not suggest that the policies we present as positive examples are perfect; each has aspects that policymakers should seek to emulate, but they also have shortcomings. For this reason, we take care to elaborate on how the policies could be improved.

Moreover, human mobility cannot be managed fully through migration policies alone. There are broader economic and other policies that have a significant effect on migrants, refugees, and their potential contributions, such as those related to social safety nets and investment climate. We also do not suggest that the positive examples can be applied in all contexts. Because different policies will work in different settings, the policies presented here should not be regarded as guides but as illustrations of the power that policymakers have to shape outcomes.

Finally, it should be noted that the current political climate around migration presents serious challenges. The bulk of new policies are meant to stop migration, not shape it. The discussion on what works and what does not must come with robust engagement with policymakers and citizens on the potential benefits of addressing migration in pragmatic, realistic ways, along with the potential costs and adjustments for certain groups. This includes a recognition that migrants and refugees will continue to move, likely in increasing numbers, and whether a person moves on regular or irregular terms in and of itself has serious policy and practical implications.

A note on terminology: throughout this paper we discuss migrants and refugees. For the sake of brevity, the term “migrants” is sometimes used to reference both refugees and immigrants. We recognize the international protections and frameworks, as well as national protections and legislation, that govern refugees and migrants are distinct and have different implications. This paper seeks to highlight common economic policy lessons, and to do so, draws on case studies of refugees and migrants, some of whom move by choice and others who move due to a complex mix of factors (including violence and threats to personal safety and dignity). This is neither intended to equate the protections, policy frameworks, circumstances, or needs of refugees and migrants, nor to presume that policy choices are equally relevant to both populations. For example, labor market gaps are not relevant criteria for accepting refugees in countries of first asylum, but lessons on effects on service delivery may be relevant to both refugees and immigrants.

This initial framing paper for Migration Is What You Make It lays out an approach for a broader research initiative to highlight the impact of different policy choices on migration’s outcomes. Our goal is not to draw blanket conclusions, but rather to draw attention to what policy choices have worked better than others in real world contexts. As we further develop the project, we welcome input and feedback on its goals, approach, and selection of case studies and key policy issues.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Marta Foresti, Jeremy Konyndyk, Kathleen Newland, and Erol Yayboke for their thoughtful comments and feedback. All errors remain our own.

1. If immigrants fill labor gaps, immigration creates jobs and raises incomes

One of the most common concerns about immigration is that it lowers wages and employment rates among natives (Nowrasteh 2018). The vast majority of research finds that the average labor market effect of immigration and refugee inflows to both developed and developing countries is small or null. However, it is true that immigration often has more adverse impacts (though still relatively small) on certain groups in the native population—particularly those that are most similar to the immigrants in terms of education and abilities.[2] When this occurs, policies that support the ability of natives to upgrade to new positions are important. But these negative effects do not always occur: even in the case of massive refugee inflows, the impact on employment and wages for natives can be negligible (Clemens and Hunt 2017).

The question for researchers and policymakers is therefore not what is the effect of immigration on labor markets, but how to create policy environments that generate positive labor market effects from immigration.

A case from Hong Kong shows that visas used to fill labor shortages can improve labor market outcomes for natives, and a case from the United States shows that placing too many application requirements on these types of visas can backfire and create negative labor market outcomes for natives.

In Hong Kong in 1986, about 2 percent of households benefited from the support of at least one foreign domestic worker (FDW). Around that time, the government introduced the foreign domestic helper program, which allows an unlimited number of immigrants to enter the country as domestic workers, providing there is demand. This led to a steady increase in the numbers of FDWs in the territory over the next two decades. By 2006, 8 percent of households—over one-third of all households with young children—had at least one FDW. Thanks to this additional domestic support, more women with young children were able to enter the labor force. Researchers estimated that, compared to women with older children, the labor force participation rate of women with children aged 0-5 increased by 10 percentage points over this period as a result of the program (Cortes and Pan 2013).

Outcomes similar to those in Hong Kong have been recorded elsewhere. In the United States, several studies have found that immigration, by increasing the supply of affordable domestic workers, caused more women with young children to be able to stay in the workforce and work longer hours (Cortes and Tessada 2011; Furtado and Hock 2010). A similar effect was found in Italy, with the additional outcome that the entrance of more women into the labor force had no effect on overall labor force participation (Barone and Mocetti 2011). In Malaysia, the effect was even larger: at one point in time, having a maid caused a woman to be 18 percentage points more likely to participate in the labor force (Tan and Gibson 2013). These studies illustrate the complementary effect of immigration, wherein immigrants, by bringing different sets of skills and motivations than natives, allow for task specialization and help natives upgrade to different forms of employment, thus creating a more efficient, productive economy and raising the income and employment rate of natives (Peri 2012).

A case from the United States illustrates the negative effect that placing restrictions can have on the labor market. US farmers can hire foreign workers to work on their farms through the H-2A visa program. As the section of this paper on legal pathways shows, this program has been instrumental in reducing unauthorized migration and helping meet farmers’ demand for labor—but it could be improved. Unlike the FDW program in Hong Kong, farm owners face a series of administrative barriers that reduce the appeal and effectiveness of the program. As a result of the barriers, the average farm pays $2,500 to receive an H-2A worker, and 72 percent of farmers received workers later in the season than they wanted due to the lengthy application process (New American Economy 2018).

Because the supply of native farm workers in some areas is virtually nonexistent, the result of these H-2A difficulties has been a labor shortage, with negative consequences rippling across the American economy (Clemens 2013; Bronars 2015).[3] From 2002 to 2014 the number of full-time crop workers fell by 20 percent, resulting in an estimated annual loss of $3.1 billion in crop production and $2.8 billion in downstream and upstream industries like transportation and irrigation. These losses imply lost job opportunities for natives (Bronars 2015). Meanwhile, it is estimated that one job is created for an American citizen for every 3 to 4.6 H-2A workers coming to North Carolina (Clemens 2013). And because so few Americans are interested in the crop working jobs, immigrants that fill them are very unlikely to displace natives. If the H-2A process were streamlined to make it easier and cheaper for American farmers to fill labor shortages, immigrants could play a complementary role to natives by boosting crop production and thus creating higher-skilled agricultural jobs and jobs in surrounding industries—all without displacing natives.

In addition to designing programs like the FDW program in Hong Kong that generate positive effects and limit or prevent negative ones for native workers, policymakers also need to implement policies and programs that support native workers who are adversely affected. As mentioned above, although average labor market effects are typically small or null, it is not uncommon for some groups in the population to be substantially harmed even while others benefit. At the same time, it is also not uncommon for natives that are displaced from employment in the short run to upgrade to better positions later (Foged and Peri 2016).

The question is how to create policies that facilitate these upgrading effects. For example, flexible labor markets have been found to minimize displacement effects (Angrist and Kugler 2003). However, for a variety of important reasons, governments may not want or be able to enact polices that improve the flexibility of labor markets, because doing so could entail lowering the minimum wage, making it easier to fire workers, and so on. Another possible approach is to institute active labor market policies, which help unemployed individuals find work. However, literature reviews have found such policies to be variably effective in both developed and developing countries (Betcherman et al. 2004; McKenzie 2017). Building on the more effective policies, more work and research is needed to determine the best ways to support native workers that experience displacement.

The cases from Hong Kong and the United States show that, instead of focusing solely on the average effects of immigration, policymakers should consider ways to enable immigration that meets labor needs, therefore enabling the complementarity of workers and encouraging upgrading among natives. In doing so, they can encourage higher wages and employment rates for the native population. But where displacement of native workers does occur, policymakers need to invest in policies and programs that support native workers as well as in building the evidence base on how best to do so.

2. Well-designed temporary migration programs fill critical labor needs, while also minimizing the risk of overstays

Temporary migration programs face suspicion on a range of issues. Common arguments against them are that their tracking measures to ensure “temporariness” are ineffective, with the result that immigrants overstay their visas and thereafter compete with natives for jobs; they deny migrants access to standard workers’ rights and protections enjoyed by citizens; and their recruitment processes are opaque and cannot be regulated by the destination country.[4] However, although each of these negative aspects has characterized some programs, a number of temporary migration programs have successfully kept visa overstay to a minimum while also bringing in migrants to fill labor shortages, offering migrant protections, and creating large economic benefits for hosts and migrants alike (Newland et al. 2008). Whether temporary migration programs create these benefits or generate negative effects depends on whether the right policies are in place.

In New Zealand, design features for a temporary migration scheme reduced overstays and created large economic benefits by introducing incentives to both employers and migrants to avoid overstays. A program in the UK, on the other hand, was unintentionally designed to encourage migrants not to return to their origin countries.

New Zealand’s seasonal migration program, the Recognised Seasonal Employer (RSE) scheme, reaps benefits not just for New Zealand and its employers, but for migrants and their origin countries. The program allows workers from Pacific Island states that have been granted low-skilled work permits to work for specific employers on a seasonal basis, most permitted to stay no longer than seven months within the 11-month seasonal period. Thanks to innovation in governance and partnerships, the program has defied the common refrain that there is no such thing as temporary migration: for the first six years of the program, it had an average overstay rate of less than 1 percent.

The program is designed to allow migrants to consistently return, such that employers in New Zealand have a reliable, familiar, and competent workforce. Term-limited seasonal work may also create a complementary effect (as described in the previous section) that boosts production and incomes for natives. The benefits for the migrants and their origin countries were significant: the workers’ household income rose by an average of about 35 percent per capita (Gibson and McKenzie 2014). Regarded by the International Labour Organization (ILO) as an example of best practice, the scheme also includes a wide range of provisions to ensure workers receive adequate protections and are informed about them (MBIE 2015; ILO 2015).

To achieve these outcomes, the RSE scheme introduced a number of innovative design features and incentives for migrant workers and employers. Notably, while a migrant worker’s stay in one season is limited, it is possible for that worker to return in subsequent years to work for the same or a different employer. This sense of job security gives workers an incentive not to overstay their visas, while also creating relative consistency and predictability within the circular design. Another part of circularity’s success appears to come from some onus being put on the employers, who are fined for migrant workers who overstay their visa (Gibson and McKenzie 2014). These fines, coupled with employers paying for half the flight and provision of housing, may incentivize employers to track their employees more closely along the circular timeline. When employers absorb some of the travel costs on behalf of migrant workers, a tendency to overstay the visa may be lessened because migrants are less likely to delay departure due to financial barriers—meaning they don’t have to wait to save enough money for the flight home (Basok 2002). The program also introduced quotas that change in response to demand, thus ensuring that employers are meeting their needs without admitting so many workers that they compete with natives (Nunns et al. 2010). Finally, the strong bilateral partnerships between New Zealand and the origin countries lay the foundation for opportunities for greater mutual benefits, including policies and programs designed to support the development of origin countries. New Zealand has in particular highlighted the benefits of remittances, and supported programs to increase migrants’ financial inclusion and financial literacy.

The RSE scheme shows that temporary migration programs can be an effective means for origin and destination countries to reap the rewards of migration without significant risk of overstay. Other programs, such as Canada’s Seasonal Agricultural Workers Program (SAWP) and Spain’s Unió de Pagesos program, have had similar success (Newland et al. 2008). Nevertheless, there is still room for improvement. For example, the RSE scheme could have included a Global Skill Partnership element (discussed in detail in the section on brain drain) wherein migrants are trained in the origin country, rendering mutual benefits through technology and skills transfer that can help drive development gains in the origin country.

Other initiatives have failed to build in the design features that allowed for successful circularity seen in RSE and similar programs. For example, the Seasonal Agricultural Workers Scheme (SAWS) in the UK has had overstay rates as high as 10 percent. The program, which started in 1945 and was discontinued in 2013, targeted eastern European agricultural/farming students to fill low-skilled temporary labor market needs for terms lasting up to six months.

One problem with the SAWS program was that although employers paid for accommodation, workers had to pay travel costs. As evidence from other examples illustrates, some workers may have had difficulty affording the return ticket at the end of the season. Second, because the program was available only for full-time students, the workers had no prospects for returning to the UK following graduation and were thus prone to overstay once they completed school. Finally, because the program targeted students, many were overqualified and thus able to find other work opportunities outside of agriculture. These job opportunities created an additional pull factor for staying (Consterdine and Samuk 2015; World Bank 2006a).

Experience in New Zealand belies the notion that low-skilled temporary migrants are bound to overstay their work authorization at high rates. Low rates of overstay are the result of pragmatic policy design and implementation that create sufficient legal migration channels to fill labor market needs; provide opportunities to migrants; and align incentives among migrants, employers, and host and origin countries. These outcomes were achieved while providing workers with adequate protections. Meanwhile, policy choices in the UK program had the effect of encouraging large numbers of workers to not return home. Temporary migration programs can generate substantial economic benefits. Whether they do so with or without large overstay rates depends on the incentives that policies create.

3. Creating legal pathways for migration can reduce irregular migration

Policymakers across the board are seeking ways to reduce irregular migration. Irregular migration is counterproductive and insecure for migrants themselves and for the origin, transit, and destination countries. Some countries are also expressly looking to reduce regular migration. There is a growing trend toward erecting walls and physical barricades to keep irregular migrants out, while curtailing legal migration pathways for migrants to enter regularly. Physical barriers and fewer regular migration pathways certainly make migration more difficult—but rather than curtail migration significantly, historical experience indicates migrants will still move by irregular means (Clemens et al. 2017).

Ultimately, countries want to regulate their immigration flows and gain better control over who enters, who exits, and on what terms. Policy choices will dictate how effective this national immigration governance can be—particularly when it comes to curtailing irregular migration. As the Bracero case from the United States shows, by sharply altering the incentives of migrants to avoid irregularity, regular channels can suppress some irregular migration. And when the opportunities to follow regular channels disappear, irregular migration re-emerges.

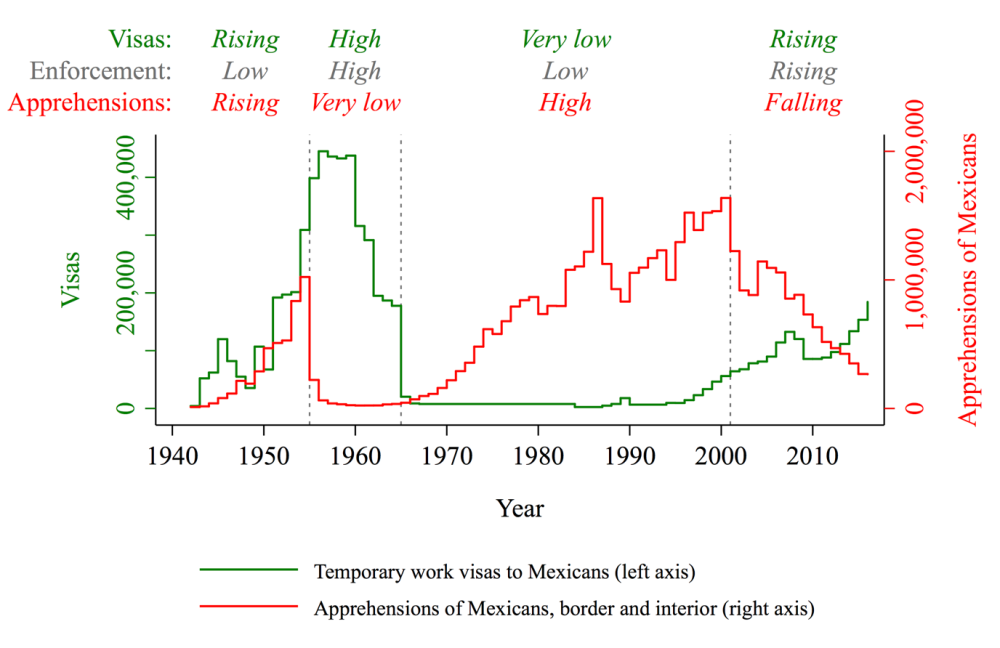

Unauthorized immigration from Mexico to the United States was nearly zero for the 10 years between 1954 and 1964 (see figure 1). This window fell between a decade of rising unauthorized immigration and the subsequent decades that saw the highest rates of unauthorized immigration to the United States of the last 80 years. What explains this anomaly? During the 10-year period, the Bracero program was at its peak, bringing in more than 400,000 seasonal workers annually between 1955 and 1965—a period when an important and practical mix of policy factors were at work (Zedillo et al. 2016).

The Bracero program was the seasonal guest worker program, primarily used by Mexican labor migrants in agriculture, that came into effect in 1942 through a series of bilateral agreements between the United States and Mexico. The first 11 years of the program had no effect on unauthorized immigration, which continued to rise. This is due to several factors, including too few visas available to match the demand for and supply of workers, and certain restrictions, such as employers not being able to select their workers or rehire previous employees (Clemens et al. 2017).

By 1954, the number of visas had risen significantly, and employers could select and rehire trusted employees from previous seasons. Simultaneously, the United States was engaged in a concerted enforcement effort, officially titled Operation Wetback. While not a series of enforcement practices that should necessarily be replicated, the overall effect of intensified enforcement coupled with sufficient legal pathways was a sharp decline in unauthorized immigration. As figure 1 shows, there was a clear correspondence between periods of high numbers of visas, high rates of enforcement, and almost zero migrant apprehensions.

Figure 1. Regular migration channels have curbed irregular migration at the US-Mexico border—when paired with robust enforcement (Clemens and Gough (2018))

With the abrupt cancellation of the Bracero program, there were essentially no low-skill work visas available to Mexicans. The job market needs remained, and grew with US demographic change in the 1980s and 1990s, creating a demand for Mexican labor migrants even on unauthorized terms. Enforcement also lessened, and unauthorized migration spiked.

At the start of the new millennium, visas available gradually began rising with the expansion of the H-2A seasonal farm worker visa—again coinciding with gradually increasing enforcement efforts (USCIS 2018). In turn, unauthorized apprehensions have been falling. Even with surges in apprehensions appearing over the past few years, these rates (with apprehensions generally in the 300,000-500,000 range annually) are still a far cry from the 1–1.5 million annual apprehensions seen in the second half of the twentieth century.

This history suggests that creating new and ample legal migration pathways, paired with incentives against unauthorized migration through enhanced enforcement, substantially substituted for previous unauthorized flows. Naturally, a variety of other factors contributed to the significant unauthorized immigration to the United States in the 1970s and 1980s, including increased development in Mexico that led to an initial boost in fertility and economic means for people to migrate—as well as a sudden economic downturn in 1982 that pushed people to look for opportunities in the United States. The end of nearly all regular migration opportunities for Mexicans into the United States made it so those migration pressures could only push people into irregular pathways.

In considering the role regular pathways may play in incentivizing or disincentivizing irregular migration, a study of asylum and short-term visa applicants in Europe in the 2000s found a corresponding relationship between rejected asylum applications and increased irregular migrants, and rejection of short-term entry visas and increased irregular migrants. The study suggests that lower asylum and visa approval rates—presumably fewer regular migration pathways—had the unintended consequence of raising the rates of irregular migration efforts (Czaika and Hobolth 2016).

Several factors beyond the number of visas available and the levels of immigration enforcement impact the unauthorized migration rates. These include demographic pressures, economic factors, and other push and pull factors that might rebalance the incentives for an unauthorized immigrant to risk a border crossing. Overall, however, a clear pattern emerges from historical experience at the US-Mexico border: efforts to curb irregular migration can be effective when made up of new regular pathways coupled with enhanced enforcement.[5]

4. The fiscal impact of new immigrants is a policy choice, with potential contributions that go far beyond individual-level taxes paid

In a 2017 speech to Congress, President Trump stoked many Americans’ fears by claiming that “our current immigration system costs American taxpayers many billions of dollars a year” (Whitehouse.gov 2017). In support of this idea, various studies have found that immigrants receive much more in benefits than they pay in taxes (e.g., Kim and Rector 2007). However, cross-country studies that consider more than immigrants’ individual tax contributions in the short-term reach much different conclusions. They almost always find that the fiscal effects of immigration are relatively minor—regardless of the income level of the host country or type of migration—and that there is variation across countries in whether the effects are mildly negative or positive (Rowthorn 2008; OECD/ILO 2018; Liebig and Mo 2013; Aiyar et al. 2016).[6] Regardless of the model or timeframe, most studies find that the fiscal impact of immigration is within 1 percent of GDP. This is a relatively small amount but in absolute terms can be quite large.

Cross-country studies also highlight that there is no single fiscal effect associated with immigration—the effect depends in large part on the policy environment. Thus, in addition to calculating the existing fiscal impact of immigration, policymakers and researchers should focus on how policy can generate more positive fiscal outcomes from immigration. The case of refugees resettled in the United States shows that policies facilitating and incentivizing labor market integration can promote refugees’ net positive fiscal contributions, and a case from Germany shows that restricting asylum seekers’ access to labor markets limits their fiscal contributions.

From 2009 to 2011, working-age refugee men in the United States were significantly more likely to be employed than native men (67 percent versus 60 percent), and refugee women were as likely to be employed as native women (Capps and Newland 2015). These rates stand out compared to many European countries, where refugees are often employed at significantly lower rates than natives. In the Netherlands, refugee men and women are over 11 and 17 percentage points less likely to be employed than their native counterparts, respectively (Joyce 2018). Partially as a result of their high rates of employment, refugees in the United States become positive net fiscal contributors relatively quickly.[7] After an average of eight years in country, refugees in the United States no longer receive more in benefits than they pay in taxes; after 20 years in country, the average refugee has paid $21,000 more in taxes than they have received in benefits (Evans and Fitzgerald 2017).

Because refugee policies affecting labor market integration in the United States differ from those in other countries in a number of ways, it is difficult to isolate a single reason why the United States has relatively high employment rates (and thus fiscal contributions) among refugees. But one of the main reasons is that the United States has policies to encourage refugees to enter the labor market quickly. For example, like many countries, the United States offers refugees a range of services to help them integrate into society. But unlike many countries, these services are designed to not disincentivize refugees from entering the labor market. Support agencies in the United States provide services to help refugees meet their basic needs for only their first 30 days in country. Afterwards, support can be extended for up to 120 days as long as refugees agree to take the first job they are offered; otherwise they have to use mainstream social benefits systems (Evans and Fitzgerald 2017; Capps and Newland 2015). In contrast, refugees in the Netherlands are given free housing and other subsidies, but they lose these benefits upon gaining employment (Economist 2015).

Another important factor less amenable to policy change is that the United States receives more resettled refugees compared to asylum seekers (Legrain 2016; Evans and Fitzgerald 2017), relative to many European countries. Before accepting refugees into the country, the United States Refugee Admission Program verifies refugee status, such that refugees do not have to go through the asylum process upon arrival and are thus able to work almost immediately (Evans and Fitzgerald 2017). This is significant because early access to labor markets is a major factor determining long-term labor market outcomes (Marbach et al. 2017; Legrain 2016).

The case of refugee integration in the United States illustrates that policies can encourage high rates of refugee employment, and that these rates can translate into net positive fiscal contributions from refugees. These lessons also apply to immigrants: one of the strongest determinants of the net fiscal contributions of immigrants (and refugees) is whether they are integrated into the labor market (Liebig and Mo 2013; Aiyar et al. 2016; Bach et al. 2017; Hanson 2009; Matthiessen 2009; Ruist 2015; Kerr and Kerr 2011). When immigrants are employed and earning more money, they will be less in need of welfare services. They will also contribute more by paying more income taxes and consuming more and thus paying more in sales taxes. Similarly, they have the potential to contribute to the productivity and output of businesses that would in turn pay more in taxes, and complement native workers, allowing them to earn more and thus pay more in taxes (Nowrasteh 2015b). And if immigrants integrate into the labor market as business owners, they may contribute to revenues by paying business tax, importing goods on which there are tariffs, or by employing others, who will in turn pay more in taxes.[8] In other words, there are many ways that working immigrants contribute to government revenues.

However, immigrants do not always have the effect of complementing workers and boosting productivity.[9] And if immigrants substitute rather than complement native workers, they may earn lower wages and thus pay less in taxes than the natives they displace, resulting in a net loss. A similar effect may occur in displacing native firms. As discussed in the labor market effects section, these displacements should be taken seriously. But given that the labor market effects of immigration are typically small or even positive in both developed and developing countries, any lost fiscal revenues from displacement are likely to be minor.[10] Thus, immigration typically has a positive fiscal effect—if a large portion of the immigrants find employment (Liebig and Mo 2013).

To help more immigrants find employment, countries can offer a variety of programs, such as language training, vocational training, or personalized plans for finding work. Many OECD countries have some form of program that helps immigrants integrate, and even more have them for refugees (OECD 2017a; OECD 2017b). However, various reviews have shown that while these programs can be a powerful tool for improving labor market outcomes for immigrants, they are sometimes ineffective and their costs are not always worth their benefits (Butschek and Walter 2014; Rinne 2012; McKenzie and Yang 2015). These reviews also acknowledge that there is a lack of evidence on the most cost-effective ways to help immigrants integrate into the labor market. We know that policies can improve labor market outcomes for immigrants, but more work is needed to determine the best ways to do so while also improving their net fiscal contribution.

Another way to improve fiscal outcomes is to simply lower restrictions that immigrants face. For example, asylum seekers in many countries are either not allowed to legally work until refugee status has been granted, or they must wait a certain period before doing so. Recent research has found that these employment bans, by deterring refugees from searching for work long after the ban has been lifted, can be detrimental to long-term employment outcomes.

A case study from Germany illustrates this point. Prior to 2000, asylum seekers in Germany were not allowed to work until being granted refugee status, and often waited in country for status determination for two years or more. Following a 2000 court ruling, asylum seekers were granted permission to work after a period of 12 months, regardless of whether they received refugee status. Both before and after this ruling, thousands of Kosovar Albanians were fleeing the war in Serbia and seeking asylum in Germany. Researchers compared two groups of Kosovar refugees: those that waited an average of 19 months before being allowed to work and those that waited 12 months. What they found was striking. Five years after being granted labor market access, the group that waited longer had an employment rate of 29 percent, compared to a rate of 49 percent for the other group—a difference of 20 percentage points. Ten years after access was granted, these rates began to merge, but the fiscal effects (not to mention the effects on the lives of the refugees) had already taken their toll. The cost of the additional seven-month ban for 40,500 refugees over a nine-year period—calculated in terms of lost tax revenue and additional welfare spending—was estimated to be 370 million Euros (Marbach et al. 2017).

Other studies have reached similar conclusions: whether by reducing asylum processing time or granting citizenship, approaches to helping refugees and other immigrants access labor markets and integrate more fully lead to higher employment rates and thus greater fiscal contributions (Hainmueller et al. 2017; Bakker et al. 2014; Gathmann and Keller 2014). That being said, there is a risk that allowing asylum seekers to access labor markets will encourage unfounded applications for asylum—particularly when combined with long asylum processing times. Thus, policies that allow asylum seekers to access labor markets should be designed considering these risks and be accompanied by efforts to mitigate them, for example through measures that reduce the processing time of asylum cases without compromising standards.

The German case shows that governments can encourage positive fiscal impacts from immigration not only by making investments, but also simply by lowering restrictions—at no cost to the government. And, as the case of refugees in the United States highlights, policies that incentivize quick integration into the labor market can be investments that pay off for refugees, immigrants, and the broader economy. These policy options are only two among many, but they illustrate that the fiscal impact of immigration is not predetermined. By creating an enabling environment for immigrants and providing integration support that makes sense for the context, governments have the power to shape the fiscal outcomes of immigration and create net gains.

5. Immigrants contribute to the economy as entrepreneurs, investors, and innovators—if they are allowed to

The contribution that immigrants make to their host economies as entrepreneurs and investors is highly variable. Immigrants in many countries tend to own businesses at higher rates than natives but, due to factors including lower levels of education, weaker language abilities, and less access to financial capital, their businesses also tend to earn less.[11] Furthermore, rather than add to economies as investors, immigrants can reduce the capital stock per worker (Dolado et al. 1994). On the other hand, they can boost entrepreneurial activity more broadly by innovating and transferring technologies (Niebuhr 2010; Markusen and Trofimenko 2009). In terms of investment, they can bring enough new capital to their host countries to offset dilution, and also increase foreign direct investment by lowering transaction costs (Javorcik et al. 2011).

Immigrants can be productive entrepreneurs and investors, but they may also make below-average contributions as entrepreneurs and investors. The question is how to encourage the former and prevent the latter. Policy differences in Turkey and Zambia show that simply lowering restrictions to business ownership for refugees can make a huge difference in the entrepreneurial contribution they make.

In contrast to the situations in many refugee-hosting developing countries, the Turkish government allows refugees to formally own business. The result is that Syrian refugees can contribute to the economy and become self-reliant. From 2011 to 2016, Syrian entrepreneurs in Turkey invested $334 million into over 6,000 formal companies. By 2016, although most Syrian firms had been operating for a short period (the average length of operation was 2.5 years), the average Syrian firm employed 9.4 people—a total of nearly 57,000 employees. And they intended to grow: the majority of small and medium enterprises (SMEs), which accounted for over a quarter of all Syrian businesses, planned to hire an additional 8.2 employees on average in 2017. These businesses were also typically run by highly educated entrepreneurs: 67 percent of Syrian business owners had a university degree or higher (Ucak 2017).

These firms benefit Turkey’s economy and citizens in many ways. Perhaps most obviously, they created employment and thus raised incomes. Of the nearly 57,000 jobs they created, most were occupied by Turkish citizens because the law requires businesses to hire Turkish citizens and refugees on a 10:1 ratio, unless they obtain a waiver (Ucak 2017). There is also evidence that the entry of Syrian firms did not displace or prevent the entry of domestic firms. In provinces with large refugee populations, there has been a large increase in the number of foreign-owned firms and no indication of a corresponding decrease in domestic firms. Rather, gross profits per capita and net sales, likely thanks to an increased demand for goods and supply of labor, have increased (Akgunduz et al. 2018). Thus, the jobs and productivity created by Syrian firms have apparently occurred without domestic firms being displaced or losing profits. The Syrian firms also have a positive fiscal impact. Since they are formally registered, they are likely to pay more in taxes than they would if they were operating informal businesses or if these Syrians were unemployed. Likewise, their employees likely consume more and thus pay more in taxes than they would without a job or with a lower-paying job. Finally, Syrian entrepreneurs have invested a great deal of capital into the country, as evidenced by large capital flows into Turkish border cities (Orhan and Gundogar 2015).

To create an environment that enabled Syrian refugees to contribute in these ways, the Turkish government enacted a simple policy: it allowed refugees to formally register their businesses. In many other refugee-hosting countries, refugees are either prohibited altogether from owning businesses or are given tacit permission to own businesses informally. However, there is a limit to how productive informal firms can be, as they cannot take advantage of formal financial services and must remain small to avoid detection (Farrell 2004). Having laws to allow formal ownership does not mean that firms will in fact formalize and increase productivity (in Turkey, as of 2016, there was at least another 4,000 informal firms in addition to the 6,000 formal)—but it provides the opportunity for them to do so (Karasapan 2017). And the potential benefits of this opportunity are evident in Turkey among Syrian entrepreneurs.

At the same time, Turkish policies toward refugee business ownership could be further improved. By limiting freedom of movement for refugees—both within and outside of the country—opportunities for some businesses, particularly those that are export-oriented and require meeting with potential clients in distant areas, are restricted. Refugee business owners also report difficulty accessing certain financial services, such as business credit cards or money transfers—problems that government intervention could potentially remedy by clarifying refugees’ rights (Ucak 2017).

Nonetheless, Turkey’s policy environment for refugee business ownership is relatively enabling. In Zambia, by contrast, policies allow refugees to formally own businesses, but the requirements are highly prohibitive. The capital investment requirement is $25,000—an exorbitant amount for refugees; they are prohibited from working in the commerce sector; and they require a letter of support from the government to register. Not surprisingly, the result is that most refugees, including business owners, work in the informal sector. This includes those refugees that are highly skilled and educated, a large portion of the refugees in Zambia (Zetter and Ruaudel 2016). This is a major missed opportunity. When allowed to work and own businesses, skilled immigrants tend to be fiscal contributors (Aiyar et al. 2016; Alden and Hammarstedt 2016; Gustafsson and Osterberg 2001; Storesletten 2004; Kerr and Kerr 2011). And, as discussed above, formal business ownership implies greater potential for tax revenue and productivity.

An enabling policy environment also makes a difference for immigrants, not only refugees. As mentioned above, immigrant businesses tend to be less productive than those of their native counterparts (Fairlie and Lofstrom 2015; Fairlie and Woodruff 2008). There is evidence that the average immigrant’s business income eventually converges with that of their average native counterpart, but also that it takes many years to do so (Lofstrom 2002). Fortunately, there are many available policy options for addressing these barriers and shortening the time of convergence: language training, engagement with financial institutions, and skills trainings are all potential ways to help immigrants reach their entrepreneurial potential sooner (European Commission 2016). Finding the right policies for a given context can make a major difference in how productive immigrant businesses are, and thus how much they contribute to host economies.

The cases of Turkey and Zambia show that if the policy environment allows and facilitates formal business ownership, refugees and immigrants will be more capable of becoming self-reliant and/or contributing as producers, employers, innovators, and taxpayers. If it does not, they will likely be less capable of employing locals, reaching their economic potential, and adding meaningfully to the economy.

6. Policy decisions in migrant origin and destination countries turn skilled migration into a drain or a gain

There is a central contradiction between the types of migration wealthy countries often say they want—skilled migrants—and the types of migration developing countries want to avoid—skilled migrants leaving. Many in origin countries view skilled migration as a drain on human capital and fiscal resources at home. By definition, if worker training is designed and planned as if workers will never move, then the emigration of even a single trained worker deprives the origin country of human capital and training expenditures from which it would otherwise have benefited.

But that is not how skilled migration always happens or must happen. Different policy choices can make skilled migration an engine of human capital creation and fiscal revenue for both migrant origin and migrant destination countries. The key is to design training systems for a world that moves.

Systems of this kind have been called Global Skill Partnerships (Clemens 2015). The Global Skill Partnership model proposes an agreement between two countries that begins by training migrants in their home countries. Not all trainees migrate, and those who remain then contribute to the local origin community with more advanced skills, capacity, and teaching potential. More broadly, the destination country and/or employer in the destination country can be directly involved in shaping the skillsets of potential migrants, while establishing training facilities and programs in the origin country. This renders a transfer of technology and capacity to the origin country that can support greater development, while ensuring the destination country and employer(s) receive migrants trained (at a lower cost than training in the destination country) for precisely the skill sets needed.

The German government has been a leading innovator in this area. It has built a series of partnerships with migrant origin countries, including Vietnam and Sri Lanka, to structure the migration of skilled nurses from those countries to Germany. In these partnerships, potential migrant nurses receive extensive training in their home countries—before they migrate—with finance and technology provided by German employers and taxpayers. Agreements of this kind strike at the heart of the global conflict over skilled migration. They ensure that Germany gets needed workers with the skills to integrate and contribute right away, while building in concrete and visible benefits for home-country training institutions. When such agreements are done right, there is skilled migration, but no drain; only shared gains. The world has only begun to explore the potential for partnerships of this kind.

Another innovation of global importance is the Australia-Pacific Training Coalition, or APTC (Clemens et al. 2015).[12] The APTC is a network of five technical training centers across the South Pacific, including in low-income countries like Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands, created by Australian aid in 2007. It has trained about 12,000 people in vocational subjects like hospitality, construction, and automobile maintenance. It was built from the ground up to grant qualifications recognized uniformly across the region, including in Australia, and to focus on skills that are needed both in migrant origin and migrant destination countries.

The APTC is part of Australia’s proactive, long-term planning for greater mobility in the South Pacific. It recognizes that climate change and other forces will create vast pressures for greater migration in the future. For migrant destination countries like Australia, that means that future migrants will either arrive with needed, recognized skills, or without those skills. For migrant origin countries like Papua New Guinea, that means that future skilled emigrants will either have their training paid for by home-country taxpayers, or by the people who will benefit most directly from emigrants’ skills.

The APTC is an innovative mechanism that both countries can use in the future to get what they want from skilled migration: shared gains rather than a drain from one to the other. What appear to be their conflicting interests do not reveal a conflict inherent to skilled migration, but the lack of creative institutional arrangements needed to resolve those conflicts in favor of mutual, tangible benefits. No mechanism like the APTC exists in any of the major migration corridors across the rest of the world.

The potential for Global Skill Partnerships extends beyond these existing successes. A key area of innovation is that of bundling together training for migrants and non-migrants in the same institutions. For example, a Global Skill Partnership between a European destination country and a nursing school in Ethiopia could create two tracks. The “home” track could train nurses for domestic service, without providing language training, employer placement, or other features critical to emigration. The “away” track could train nurses expressly for service at the European destination. Students could join either track according to their goals, while officials and employers in the destination country would provide technical and financial support to both tracks—strengthening the entire institution. This can be highly cost-effective for destination countries: training a nurse in Europe is an order of magnitude more expensive than training both a home-track nurse and an away-track nurse in parts of Africa. This bundling of the two tracks means that the program visibly, tangibly creates human capital for the origin country, rather than being seen to drain it away.[13]

None of this is to say that skilled migration is a force for harm in the absence of Global Skill Partnerships. Skilled migration generates massive inflows of remittances, new technologies, trade, investment, and entrepreneurship for many countries of migrant origin around the world. Countries with more skilled emigrants create greater demand for skill at home, develop the capacity to manufacture and export a broader range of goods, and become more democratic over time (Clemens 2016). In other words, ideas and economic exchange flow through people, and the movement of skilled people is therefore part of the process of economic development. These extensive and diffuse benefits intermingle with the obvious and direct absence of a skilled person from the place they leave. Such complexity is why there is no evidence of any kind that restrictions on skilled emigration have caused improved development outcomes in any low-income country.

Global Skill Partnerships can make shared gains obvious and visible to the people who live with the consequences. Drains and gains are bound up in complex ways when skilled people migrate. Neither is inherent to the movement of a person with skill. But policy has shaped the degree and distribution of benefits, turning apparent drains into concrete and mutual gains. Innovation in this area has only begun, and the coming century needs enormously more of it.

7. With well-designed policies, immigrants can have a positive impact on the quality of service delivery

It is commonly believed that immigrants reduce the quality of public services in host countries by overusing these services and burdening service providers. Embodying this belief, critics of immigration often claim that immigrants rely heavily on welfare and strain the public health system (Whitehouse.gov 2017). In reality, these criticisms are largely overblown. For example, immigrants in some countries use welfare services at only slightly higher rates than natives, and in other countries they use them at lower rates (Barret and McCarthy 2008). And, as mentioned in a previous section, their fiscal contributions often more than offset their use of welfare.

That being said, the concern that immigration can decrease the quality of services should be taken seriously: as we show, immigration and refugee inflows have been found to harm the quality of or access to health and education services. At the same time, inflows have also been found to improve the health and education outcomes. As seen in Zaire and Guinea—where governments and donors responded very differently to refugee inflows—the impact of immigration on service quality depends on policy. In Guinea, the government and donors cooperated to create an integrated health system that led to improved health outcomes for all. In Zaire, an uncoordinated response led to a deterioration of the local health system.

In the early 1990s, roughly 500,000 refugees of the Liberian and Sierra Leonean civil wars made their way into Guinea. Responding to this crisis, UNHCR worked with the Guinean government to develop an integrated, coordinated plan for assisting the refugees and ensuring equitable outcomes for the host population. In terms of health services, this meant bolstering the existing Guinean health system and providing free and equal access to health services for refugees and Guineans alike. In the district of Guéckédou, for example, international actors and the government worked together to repair the local hospital, train staff, increase the availability and quality of medical supplies, and construct a new hospital and two dozen health centers. As a result, refugees were given the care they needed, and the host community experienced an improvement relative to the pre-refugee period in access to health care, as measured by the rate of major obstetric interventions—an indicator that was chosen in part for being “sensitive to show improved access to health services.” In areas with low numbers of refugees, the rate of major obstetric interventions increased significantly, from 0.07 percent to 0.27 percent. In areas with high numbers of refugees, the rate increased even more—from 0.34 percent to 0.92 percent (Van Damme et al. 1998).

The response in Guinea provides an example of how smart policies can help maintain quality services in the face of large refugee inflows. The response in Zaire shows what can happen without these policies. Following the 1994 genocide in Rwanda, hundreds of thousands of refugees flowed into neighboring Zaire (today the Democratic Republic of the Congo). The international community responded with extensive humanitarian relief, including health services. Despite the fact that refugees were free to access local health centers, the host community was not allowed to access the refugee health centers. At the same time, since humanitarian organizations offered much larger salaries, many health workers left local hospitals or clinics for the refugee-based health centers. The result was a large increase in caseloads for local health centers that had fewer staff: in the aftermath of the influx, consultations increased by as much as 750 percent at one health center, and 25 percent of the administrative staff in one district left for humanitarian organizations. And although donors provided some financial and in-kind assistance to the local health system, it was not enough to compensate for the new challenges. The quality of and access to health services for locals decreased substantially in the aftermath of the refugee influx: hospitalization of locals at one hospital decreased by 30 percent; in one district, only 13 of 23 health centers remained functional (Goyens et al. 1996).

These Zairean and Guinean cases illustrate broader trends. In a series of broad cross-country reviews, two different studies by Hynes et al. (2002) and Hynes et al. (2012) found refugees often have superior health outcomes compared to their host counterparts (though certainly not always), and a lack of integration is a contributing factor to this disparity. Meanwhile, integration helped to either generate improved health outcomes or support burdened health systems in Cameroon, Uganda, and Lebanon (Tatah et al. 2016; Orach and De Brouwere 2006; Ammar et al. 2016). Clearly, policy choices and implementation play a major role in determining the impact that immigrants and refugees have on service quality. If systems adapt to refugee or immigrant inflows, they can provide refugees with the services they need while improving outcomes for hosts. If they do not, they may be overwhelmed.

These lessons extend beyond refugee inflows in developing countries. While parallel (as opposed to integrated) refugee health systems are not found in developed countries, there are still concerns that refugees or immigrants more broadly may burden health, welfare, or education systems and reduce service quality. Research on the impact of immigration on education systems finds that these concerns are valid and can potentially be addressed by policy: sometimes immigration has no impact on education quality and can even improve quality, (e.g., Ohinata and van Ours 2013; Geay et al. 2013; Hunt 2015), though in other cases it has harmful effects (e.g., Gould et al. 2009).

Negative effects tend to occur in situations where there is an especially large concentration of immigrants (Brunello and Rocco 2013; Pedraja-Chaparro et al. 2015). This means that policies designed to reduce the concentration of immigrants in certain schools could mitigate negative effects. That being said, it is not easy to do so, and past attempts have had limited effectiveness (Iceland 2014). Thus, where there are negative effects on service quality, designing and implementing policies that mitigate them can be challenging and may require innovative approaches. But as the cases from Zaire and Guinea show, well-designed policies—even those that are difficult to carry out, such as the integration of health systems—can help ensure that the integrity of services is maintained or improved.

Conclusion

With a growing labor force in low- and middle-income countries, rising pressures for emigration in countries transitioning to middle-income status, continued conflict and crises, and limited proven means for deterring migration in the longer term, growth in international mobility is all but inevitable. Meanwhile, there are large opportunities for mutual benefit from migration—as well as potential costs. It is therefore imperative for policymakers to consider the best ways to manage migration flows in order to capture the mutual benefits and avoid negative effects.

In this paper, we presented a preliminary overview of case studies illustrating decisions that policymakers have taken to better harness the benefits of migration. The cases also indicate that effective policies are often not easy to enact. They can be technically and politically challenging to implement and doing so requires leadership, commitment, cooperation, and investment. But they also show that when political will and resources are mobilized, policies can encourage migration that creates jobs for natives, helps migrants become net fiscal contributors, maintains or improves the quality of services during large refugee or migrant inflows, discourages illegal migration while simultaneously filling labor shortages with truly temporary visas, facilitates immigrants’ contributions as innovators and entrepreneurs, and turns skilled migration into shared gains.

The beneficial policies we have highlighted in the case studies are not perfect, and they represent only a few of the many possible approaches to generating positive effects from migration. They do illustrate the fact that the effects of migration—whether by refugees or other migrants, to developed or developing countries—are a policy choice. It is ultimately up to policymakers to determine which of the many available approaches make the most sense in a given context.

Given charged debates over migrants and refugees in Europe, the United States, and elsewhere, we do not expect research and evidence to drastically alter near-term policy discussion. But for those seeking to help realize the benefits of migration and avoid its harms in the coming decades, now is the time to chart an ambitious agenda around research, communications, and convening. These are key areas where a broad coalition of experts, practitioners, and policymakers could collaborate to promote more productive and evidence-informed dialogue:

-

Research and evidence: Although the literature on migration is substantial, there are still many unanswered questions with critical relevance to policymakers. In this paper, we have highlighted a handful of research questions, without attempting to be systematic or exhaustive. For example, policymakers would benefit from more research on policies and programs that can effectively support native workers who may face displacement and have limited opportunities for occupational upgrading. More research is also needed on what works to mitigate negative effects of migrants and refugees on service delivery systems where these effects exist; the relationship between legal pathways and irregular migration, including the effects of increased enforcement; and capturing the full fiscal impact of refugees and migrants beyond individual-level taxes. There are many other important topics. A potential way forward would be to convene a group of researchers and policymakers to map and prioritize research questions.

-

Communications: We know that research and evidence are only the first step, and many groups (not only migration experts) are struggling to adapt their outreach and communications for the social media age. There is a need to develop compelling stories, new narrative forms and platforms, and sophisticated outreach strategies in collaboration with communications professionals. Public narratives around migration have shifted sharply, and a coordinated effort to understand the landscape could help lay the groundwork for efforts to promote more evidence-informed public discourse.

-

Convening: A critical component of improved research and communications is convening across a broad spectrum of views to better understand the sticking points in migration conversations. This paper is focused on the economic aspects of migration, but the discussion must be broader to include social, political economy, and security considerations, real and perceived. While high-level convening has occurred around the Global Compact on Refugees and Global Compact for Migration, there is need for broader and deeper engagement in the years to come.

This framing paper is only the beginning of Migration Is What You Make It. By further developing and elucidating evidence and lessons from experience, we aim to support policymakers grappling with difficult choices and contribute to global and local discussions on how to help harness the benefits of migration and mitigate negative effects. In partnership with a range of research, civil society, private sector, government, multilateral, and other actors, we plan to further explore and refine potential case studies and policy lessons with the goal of making evidence more accessible and compelling to those working in policy and media. We hope Migration Is What You Make It can help shift the discussion from how much migration to how different policy choices can generate positive effects from immigration and avoid negative ones.

[1] Unless otherwise noted, population predictions are taken from the United Nations 2017 World Population Prospects Data: https://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp/.

[2] For thorough reviews of the literature on labor market effects see Bohme and Kups (2017) and Okkerse (2008).

[3] For another example of the negative effects of labor shortages, see Dance (2018).

[4] For examples of the issue of visa overstay and ineffective tracking see DHS (2016) and Nixon (2017). For an example of the critique that many temporary migrants overstay their visas and continue to work illegally see Massey (1989). For a discussion of protection and recruitment issues see Cholewinski (2005).

[5] Evidence from the US-Mexico border merits scrutiny in light of today’s related demographic and economic pressures between sub-Saharan Africa and Europe (Hanson and McIntosh 2016).

[6] These more nuanced studies use dynamic, rather than static, models to assess fiscal costs. Dynamic models are more comprehensive and realistic measures of fiscal impacts because they account for the effects of immigrants on the economy, long-term effects (i.e., their effects over a lifetime rather than their effects in one year or several years), and/or the effects of second- and third-generation immigrants (Nowrasteh 2015b). In fact, the very study that President Trump cited in his speech also found that, when applying a dynamic model that accounts for future revenues generated by immigrants, the 75-year net present value of a new immigrant to the United States is positive $259,000 (Blau and Mackie 2017).

[7] For comparison, see Alden and Hammarstedt (2016) for a calculation of the long-term fiscal cost of refugees in Sweden.

[8] Tax structures in developing countries differ from those in developed countries, such that business and income taxes represent a smaller share of revenues. However, they still usually account for a substantial share. Thus, the channels mentioned here by which immigrants can contribute are relevant in developing countries as well as developed countries (OECD/ILO 2018).

[9] For examples of substitution and displacement see Federman et al. (2006) and Calderon-Mejia and Ibanez (2016). For an example of immigrants failing to boost productivity see Ortega and Peri (2009).

[10] For a review of this literature see Bohme and Kups (2017).

[11] For examples of immigrants owning businesses at higher rates see Andersson and Wadensjö (2004) and Schuetze and Antecol (2006). For examples of their businesses earning less and reasons why, see Fairlie and Lofstrom (2015) and Fairlie and Woodruff (2008).

[12] Until a recent change, the APTC was named the Australia-Pacific Technical College.

[13] The APTC currently plans to experiment with precisely this kind of two-track system over the next five years: http://www.devpolicy.org/whats-different-aptc-next-stage-20171018

References

Aiyar, Shekar, Bergljot Barkbu, Nicoletta Batini, Helge Berger, Enrica Detragiache, Allan Dizioli, Christian Ebeke, Huidan Lin, Linda Kaltani, Sebastian Sosa, Antonio Spilimbergo, and Petia Topalova (2016), “The Refugee Surge in Europe: Economic Challenges,” IMF Staff Discussion Note. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund.

Akgunduz, Yusuf Emre, Marcel van der Berg, and Wolter Hassink (2018), “The Impact of the Syrian Refugee Crisis on Firm Entry and Performance in Turkey,” The World Bank Economic Review, 32 (1): 19-40.

Alden, Lina and Mats Hammarstedt (2016), “Refugee immigration and public sector finances: Longitudinal evidence from Sweden,” Vaxjo, Sweden: Linnaeus University Labour Market and Discrimination Studies.

Ambler, Kate, Diego Aycinena, and Dean Yang (2015), “Channeling Remittances to Education: A Field Experiment among Migrants from El Salvador,” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 7 (2): 207-232.

Ammar, Walid, Ola Kdouh, Rawan Hammoud, Randa Hamadeh, Hilda Harb, Zeina Ammar, Rifat Atun, David Christiani, and Pierre A. Zalloua (2016), “Health system resilience: Lebanon and the Syrian refugee crisis,” The Journal of Global Health, 6 (2).

Andersson, Pernilla and Eskil Wadensjö (2004), “Self-Employed Immigrants in Denmark and Sweden: A Way to Economic Self-Reliance?,” IZA Discussion Paper 1130. Bonn, Germany: Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA).

Angrist, Joshua D. and Adriana D. Kugler (2003), “Protective or Counter-Productive? Labour Market Institutions and the Effect of Immigration on EU Natives,” Economic Journal, 113.

Bach, Stefan, Herbert Brucker, Peter Haan, Agnese Romiti, Kristina van Deuverden, and Ezno Weber (2017), “Refugee integration: a worthwhile investment,” DIW Economic Bulletin, 3: 33-43.

Barone, Guglielmo and Sauro Mocetti (2011), “With a Little Help from Abroad: The Effect of Low-skilled Immigration on the Female Labour Supply,” Labour Economics, 18 (5): 664-675.

Bakker, Linda, Jaco Dagevos, and Godfried Engbersen (2014), “The Importance of Resources and Security in the Socio-Economic Integration of Refugees. A Study on the Impact of Length of Stay in Asylum Accommodation and Residence Status on Socio-Economic Integration for the Four Largest Refugee Groups in the Netherlands,” Journal of International Migration and Integration, 15 (3): 431-448.

Barret, Alan and Yvonne McCarthy (2008), “Immigrants and welfare programmes: exploring the interactions between immigrant characteristics, immigrant welfare dependence, and welfare policy,” Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 24 (3): 542-559.

Basok, Tanya (2002), “He Came, He Saw, He Stayed. Guest Worker Programmes and the Issue of Non‐Return,” International Migration, 38 (2): 215-238.

Basok, Tanya (2007), “Canada's Temporary Migration Program: A Model Despite Flaws,” Migration Policy Institute.

Bennett, Christina (2016), “Time to Let Go: A Three-Point Proposal to Change the Humanitarian System,” London, UK: ODI Humanitarian Policy Group.

Bertoli, Simone (2017), “Is the Mediterranean the New Rio Grande? A Comment,” Italian Economic Journal, 3 (2): 255-259.

Betcherman, Gordon, Karina Olivas, and Amit Dar (2004), “Impacts of Active Labor Market Programs: New Evidence from Evaluations with Particular Attention to Developing and Transition Countries,” Social Protection Discussion Paper Series, Washington, DC: World Bank.

Betts, Alexander, Louise Bloom, Josiah Kaplan, and Naohiko Omata (2014), Refugee Economies: Rethinking Popular Assumptions, University of Oxford University: Humanitarian Innovation Project.

Blau, Francine D. and Christopher Mackie (2017), The Economic and Fiscal Consequences of Immigration, Washington, DC: The National Academies of Sciences.

Bohme, Marcus H. and Sarah Kups (2017), "The economic effects of labour immigration in developing countries: A literature review", OECD Development Centre Working Paper 335, Paris, France: OECD Publishing.

Bronars, Stephen G. (2015), A Vanishing Breed: How the Decline in U.S. Farm Laborers Over the Last Decade Has Hurt the U.S. Economy and Slowed Production on American Farms, the Partnership for a New American Economy.

Brunello, Giorgio and Lorenzo Rocco (2013), “The effect of immigration on the school performance of natives: Cross country evidence using PISA test scores,” Economic of Education Review, 32: 234-246.

Butschek, Sebastian and Thomas Walter (2014), “What active labour market programmes work for immigrants in Europe? A meta-analysis of the evaluation literature,” IZA Journal of Migration, 3: 48.

Carletto, Calogero, Katia Covarrubias, and John A. Maluccio (2011), “Migration and Child Growth in Rural Guatemala,” Food Policy, 36 (1): 16-27.

Calderon-Mejia, Valentina and Ana Maria Ibanez (2016), “Labour market effects of migration-related supply shocks: evidence from internal refugees in Colombia,” Journal of Economic Geography, 16 (3): 695-713.

Capps, Randy and Kathleen Newland (2015), The Integration Outcomes of U.S. Refugees, Migration Policy Institute.

Chojnicki, Xavier (2011), “Impact budgétaire de l’immigration en France,” Revue Economique, 62: 531-543.

Cholewinski, Ryszard (2005), “Protecting Migrant Workers in a Globalized World,” Migration Policy Institute.