Recommended

Several aspects of Pakistan’s recent economic history show why it has been so difficult to service the external debt and why this will continue to be a challenge in the future. First, external debt has not been used to expand public investment for many years now; instead, it has largely supported government consumption. Second, the ability to service the debt has been weakened by poor export performance. And while maintaining external balance has been helped by the growth of remittances, this very growth has also generated pressure on the exchange rate to appreciate, thereby undermining the incentive to export. Third, the pro-consumption bias of the external debt has been exacerbated by the increasing reliance on quick-disbursing funds provided by international financial institutions to promote policy reforms and rebuild international reserves. Fourth, debt terms have been deteriorating for a while as interest rates applicable to Pakistan have risen. These four points are elaborated below.

External debt has been used primarily to support government consumption

The underlying logic of borrowing from external sources is that it enables a country constrained by low domestic savings to use foreign savings to finance productive investments. Such investments, in turn, are expected to generate resources, over time, with which the debt can be serviced and repaid. Several observations suggest, however, that the borrowing, investment, and repayment process has not worked along these lines in Pakistan.

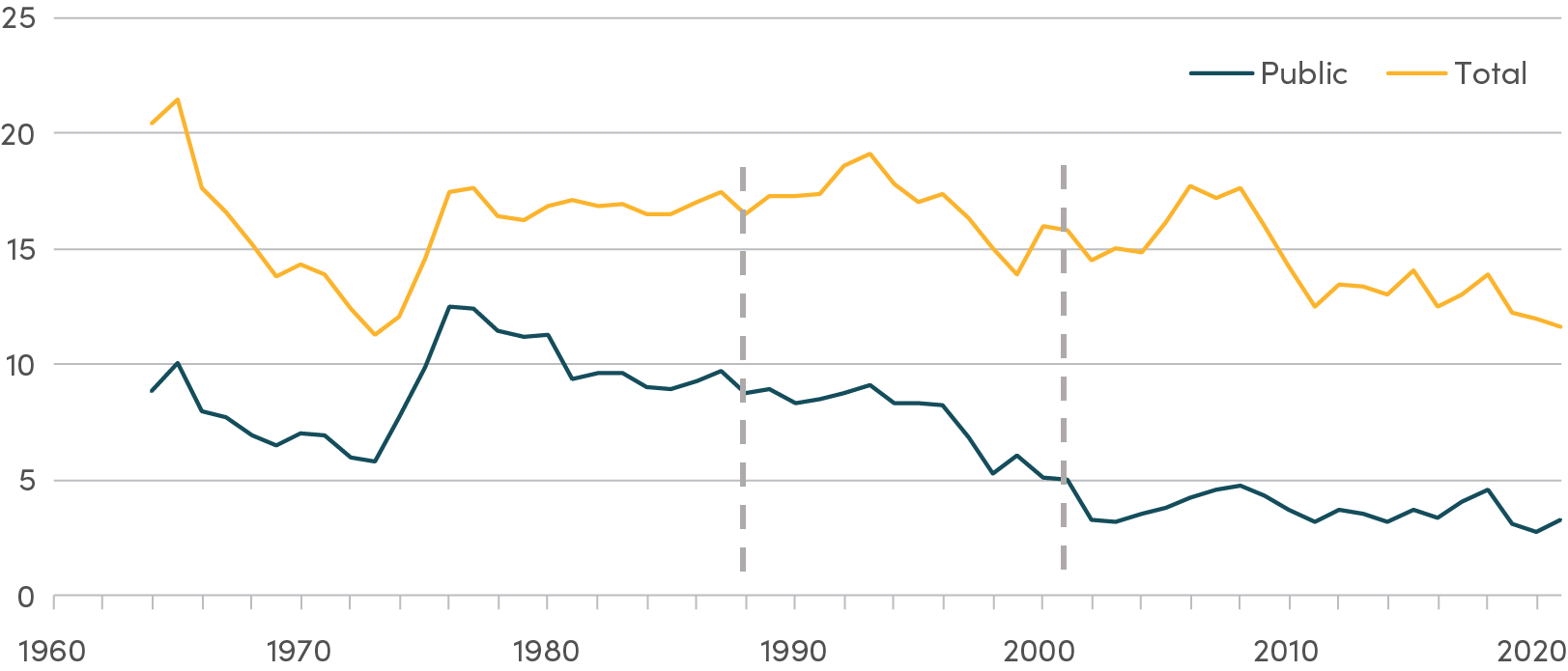

One relevant observation is the fact that public (and total) investment rates have fallen rather than risen since the mid-1970s. This can be seen from Figure 1. Public investment rates have fallen from a level of 12 percent of GDP in the mid-1970s to under 5 percent for the past two decades. This means that even where external debt was specifically assigned to investment projects, as is the case for many loans from the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank, the government of Pakistan reduced its own domestic-currency investment efforts by so much that overall public investment declined.

Figure 1. Stagnating investment rates

Source: World Development Indicators

So, what has external debt financed in Pakistan? Looked at from an aggregate macroeconomic perspective, it has largely financed public consumption. Figure 2 shows how government spending has behaved in the last two decades. It has risen by 5 percentage points of GDP during 2001-2022, from 15 percent to 20 percent of GDP. The ratio declines a little every time Pakistan is under an IMF program (as after 2008, 2013 and 2019) but it quickly returns to an elevated level one or two years before an election is due as the government of the day seeks to use fiscal largesse to retain important party members and influence voters. [1]

Figure 2. Government expenditure to GDP (%)

Source: International Monetary Fund

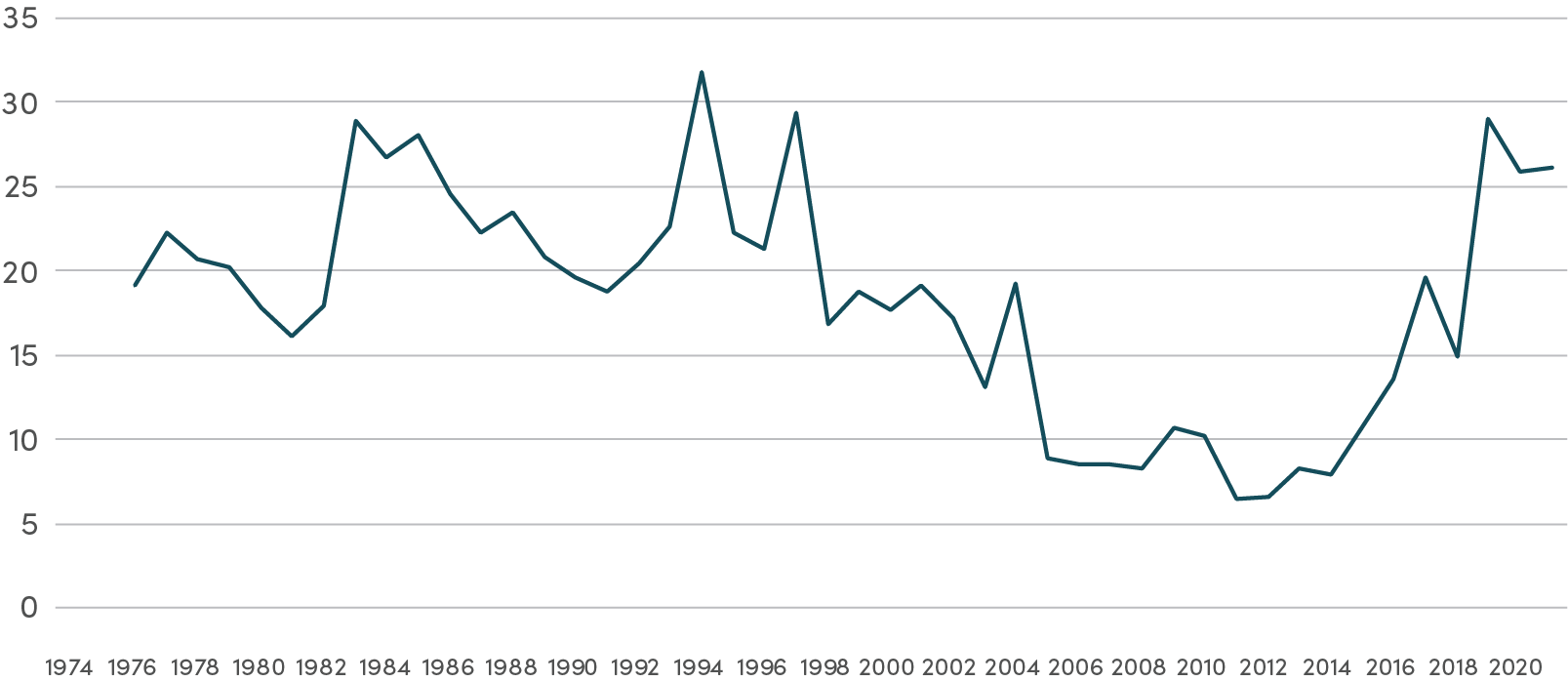

Since consumption does not generate returns from which to repay the debt, one should expect Pakistan to have run into repayment problems over this period. As indeed it did. Figure 3 shows how the ratio of debt servicing claims to export earnings has moved over the relevant period. It shows several peaks when the ratio rose to 30 percent of exports, one in the early 1980s, then twice in the 1990s and finally one more recently in 2018. Each peak was associated with repayment crises. The crisis of 1998-2001 led to a default followed by a debt restructuring arranged with external creditors. This gave the country some breathing room to reorient its economic policy priorities. Despite the improved debt servicing profile thus achieved, Pakistan has gone back to the IMF for emergency financing four times since 2001. Pakistan is currently under an IMF program which will expire by mid-2024. Meanwhile, the debt servicing ratio and other macro trends suggest that another IMF program will be required soon thereafter. The debt servicing ratio is close to 30 percent of export earnings, the same peak at which a default occurred in 1999 and the debt was restructured.[2]

Figure 3. Public and publicly guaranteed debt service (% of exports of goods, services, and primary income)

Source: World Development Indicators

Debt servicing has been hampered by poor export performance

The low investment rate is one reason for the country’s lack of resources with which to repay its debt. Another is the stagnation in export earnings experienced over the past twenty-five years. As shown in Figure 4, export earnings peaked at around 15 percent of GDP in the early 1990s and have since declined to around 8 percent of GDP. Meanwhile, the consumption orientation of the Pakistani economy has kept the import ratio much higher, at around 22 percent of GDP. Financing the trade gap in addition to foreign debt servicing has proved difficult for Pakistan for close to three decades now.

Figure 4. Trade performance: Imports and exports (% GDP)

Source: World Development Indicators

Help towards financing the external deficit has come from rising remittances from an extensive diaspora, especially in the GCC countries. But this has not been enough to cover the total foreign exchange needed to finance imports and service external debt. Annual shortfalls have been met in large part through new loans from bilateral lenders (especially China) and multilateral sources (such as the ADB, the World Bank and the IMF). Grants have also helped but their path has been dominated by political factors such as the extent to which Pakistan was involved in the US-led war in Afghanistan since 2001.

Remittances have helped improve living conditions (especially for low-income families) and have stimulated economic activity in home construction, transportation, and retail, but have also had the undesirable effect of putting upward pressure on the real effective exchange rate.[3] Poor management of such pressure by the Pakistani authorities led to the path of exchange rate appreciation shown in Figure 5. As can be seen, the exchange rate has been overvalued for many years during the past twenty years. Periodic devaluations have occurred to relieve the pressure on exports and to constrain imports, especially when the country has been under an IMF program. But there has been no sustained commitment among Pakistan’s political or bureaucratic managers to a competitive exchange rate management policy. This, combined with insufficient public investment to strengthen the competitiveness of firms, has adversely affected export performance. [4]

Figure 5. Real effective exchange rate movements

Pro-consumption bias has been promoted by quick-disbursing policy reform loans

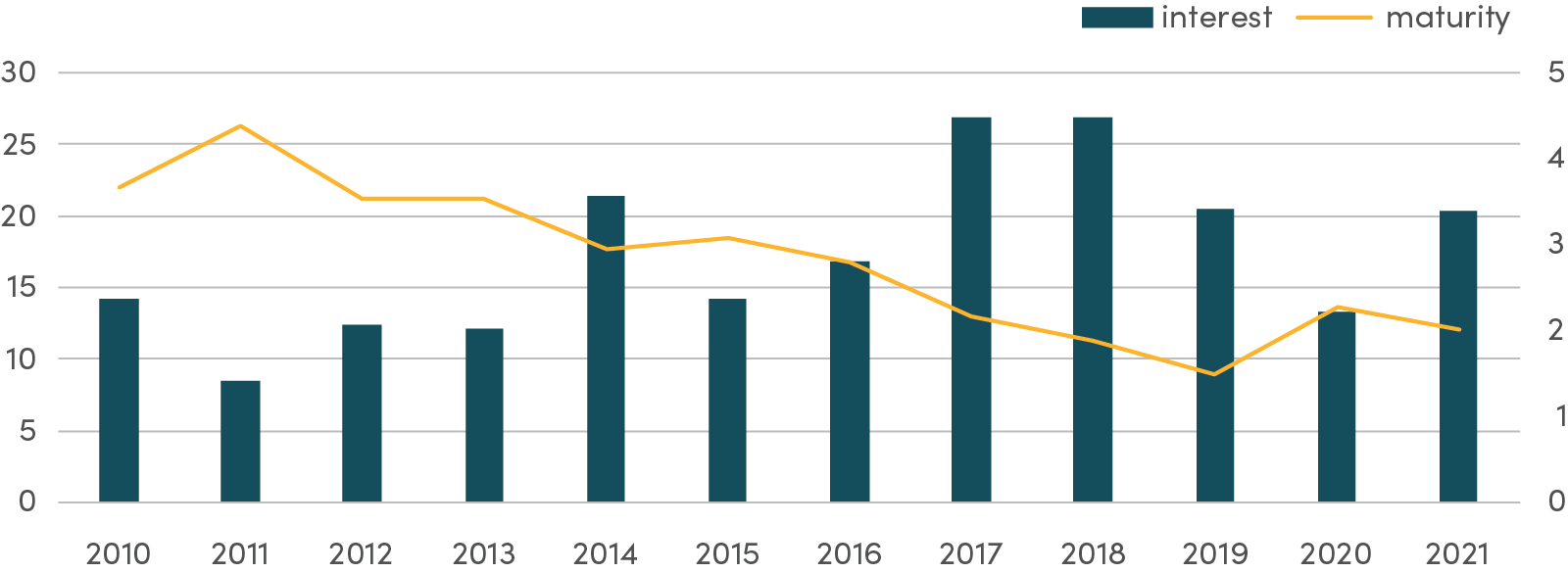

The trend towards using external debt for consumption rather than investment was supported by a shift in the portfolios of multilateral development agencies towards quick-disbursing loans. Figure 6 shows how the portfolio of the World Bank has evolved over the last four decades. It shows a clear uptick in budget support loans since 2010. Budget support loans are relatively large loans that are disbursed quickly in two or three instalments in support of policy reforms promised by the authorities. Since they are not related to any project investments, they do not directly generate resources with which to meet the associated debt servicing. Those resources are expected to come instead from the impact of policy reforms on national economic productivity. Unfortunately, this has not happened in Pakistan. The quick disbursing funds have instead gone into public consumption and have led to exchange rate appreciation. For Pakistan, the correlation of trends in budget support loans and the real effective exchange rate is especially notable for the period since 2010.

Figure 6. World Bank loans to Pakistan: Budget support/annual net committed

Source: World Bank

Loan terms have been hardening

External debt may be divided into credits and loans. Credits refer to heavily concessional loans from IDA (an arm of the World Bank) and from regional development banks of which the Asian Development Bank is the most important source for Pakistan. These are offered at very long maturities (30-40 years) and do not carry interest charges, only administrative fees. All other sources of official debt carry higher interest rates and are of shorter duration. They come from a variety of multilateral sources (such as IBRD, ADB and IMF) and bilateral sources (such as China, Japan, KSA, UAE, USA, and others). The multilateral sources typically price their loans off some international benchmark such as LIBOR. Bilateral sources exercise discretion in what they charge as such loans are also considered elements of their foreign policies. Still, loans imply more of a burden than credits and any shift in the relative shares of credits and loans affects the long-term profile of debt servicing. Note that we are not considering the flow of grants here since grants are not classified as debt and do not have to be repaid. Note also that grants tend to exacerbate the pro-consumption bias of external inflows for Pakistan.

Pakistan’s access to concessional funding has changed over time. As its income rose, terms for multilateral institutions loans hardened, shifting from IDA credits to IBRD loans with respect to the World Bank. A similar hardening of terms occurred with the Asian Development Bank. At the same time, while bilateral loans poured in during the aftermath of 9/11, they have by now significantly declined. These trends are shown in Figures 7 and 8.

Figure 7. Trends in concessional external finance

Source: International Debt Statistics, World Bank

Figure 8. Trends in loan terms

Source: International Debt Statistics, World Bank.

Concluding remarks

The four factors discussed above continue to operate in Pakistan. External finance does not enhance public or total investment. Instead, at the macro level, it supports rising public spending. This means that resources for debt servicing are not being generated by the uses to which the net additional debt is put. At the same time, export performance remains poor, an outcome attributed mostly to poor exchange rate management, low public investment, and other anti-export biases in the policy framework. Export performance is episodically improved by depreciation brought about by IMF programs, but the improvement is not sustained as political, bureaucratic, and business interests coalesce repeatedly into pro-consumption coalitions. Ongoing changes in the priorities of the multilateral development agencies continue to support a shift towards quick-disbursing loans not linked to public investments but to policy reforms. The policy reforms undertaken to date have not yet paid off in additional productivity for Pakistan for various reasons. Meanwhile, quick-disbursing loans have supported the fiscal deficit orientation of the public sector. Finally, loan terms have been hardening over the last two decades as Pakistan is no longer considered a least-developed country. Meanwhile, international interest rates have been rising since the end of the Great Moderation in the crisis of 2007-08. This trend is likely to continue for some time, affecting the terms at which multilateral development agencies lend to Pakistan.

Pakistan has just had an election and the expectation is that the government will take the needed tough decisions for fiscal consolidation (raising revenue and directing public expenditure towards productive investments) and restoration of international competitiveness – the key determinants of external debt sustainability. This will require taking on powerful interest groups who benefit from the current structure of unproductive subsidies and exchange rate management tilted towards appreciation. It will also require bringing into the tax net all those who belong there - real estate developers, retail and wholesale traders and large farmers. The army leadership, widely believed to have influence over political and bureaucratic functionaries, will have to take full ownership of reform.

The new government, provided it is committed to reform, will require fiscal headroom to strengthen productivity and take measures to counter climate change events (to which Pakistan is highly vulnerable). Restructuring of external debt will provide the needed fiscal space and thus will be essential. Pakistan’s external debt is owed largely to the IFI’s, and they bear some responsibility for geo-political lending to Pakistan, especially when there was evidence that fiscal profligacy was unchecked and the capacity to service loans with export earnings was eroding.

References

Diaz-Cassou, J., Erce, A., and Vazquez-Zamora, J., (2008). Recent Episodes of Sovereign Debt Restructurings: A Case Study Approach, Banco do Espana Occasional Paper 0804. Accessed at: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1210382.

Iqbal, F. and Nabi, I., (2024). “Pakistan’s External Debt: Trends, Outcomes, and Sustainability.” Paper prepared for Finance for Development Lab, CEPREMAP - Paris School of Economics.

Jafarey, S., Maak, A.K., Nabi, I., and Qureshi, I. (2023). “Are Overseas Remittances a Source of Dutch Disease in Pakistan?” Paper prepared for Finance for Development Lab, CEPREMAP - Paris School of Economics.

Research and analytic assistance for the paper was provided by Izza Malik, Aziz Khan and Bilal Ayaz Butt.

[1] Iqbal and Nabi (2024) show a statistically significant negative relationship between external debt and total investment in Pakistan during 1987-2022.

[2] The debt restructuring negotiated during 1999-2001 is described in Diaz-Cassou et al., (2008).

[3] See Jafarey et al., (2024). Using Local Projection techniques to generate impulse response functions, this paper finds evidence that remittances have been associated with real exchange rate appreciation in Pakistan.

[4] Iqbal and Nabi (2024) show a negative but statistically significant correlation between rising external debt and falling exports in Pakistan for the period 1987-2022.

Rights & Permissions

You may use and disseminate CGD’s publications under these conditions.