Recommended

This piece was also published by the Consortium for Development Policy Research (CDPR) here.

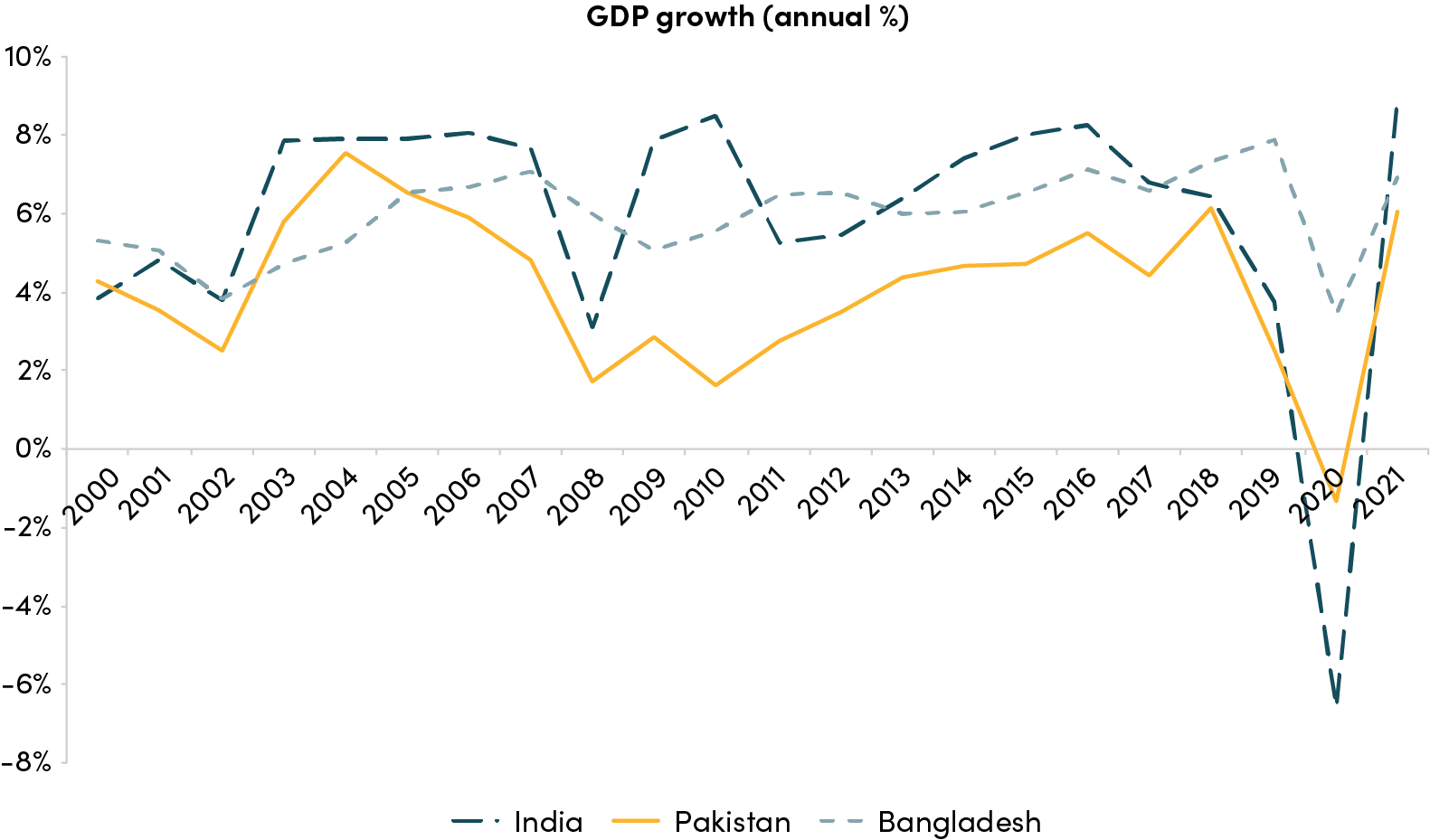

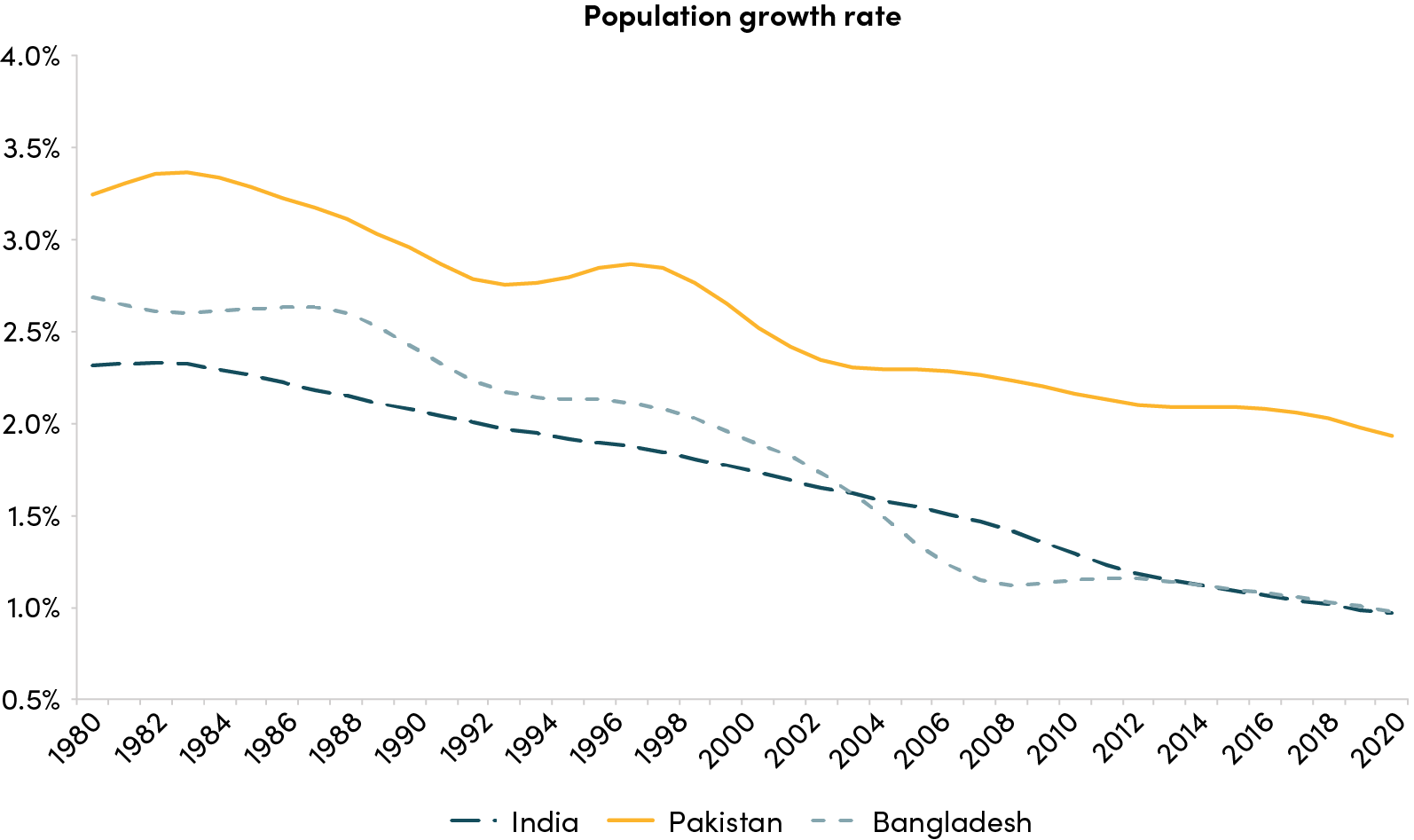

The unprecedented turnout at rallies across Pakistan protesting corruption and poor job prospects underscores the frustration among the rapidly growing middle class with governance failures. Pakistan’s economic growth exceeded India’s for over four decades after its independence in 1947, but since the 1990s, its growth rate has been consistently lower than India’s (Figure 1). And, given Pakistan’s higher population growth (Figure 2), its per capita income—a third higher than India’s in 2000—is now, 20 years later, a third lower. Pakistan has transitioned from the poster child of development to the sick man of emerging markets. For a country with a population of 220 million and on the frontlines of the fallout from global warming, this is not encouraging.

Figure 1. Pakistan’s growth rate has been consistently lower than India’s since the 1990s.

Source: World Development Indicators, World Bank

Figure 2. Decline in Pakistan’s population growth much slower than in India and Bangladesh

Source: World Development Indicators, World Bank

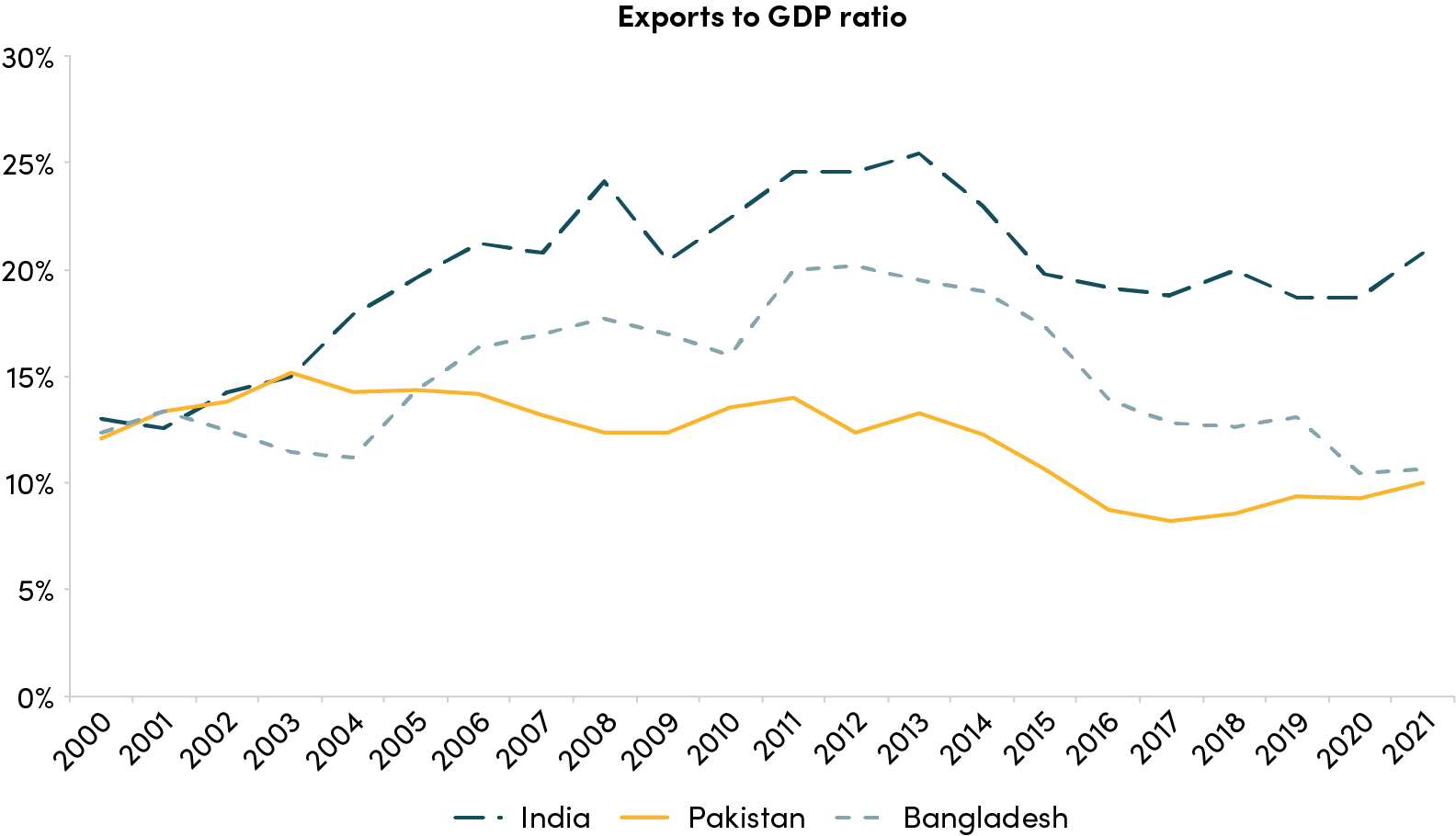

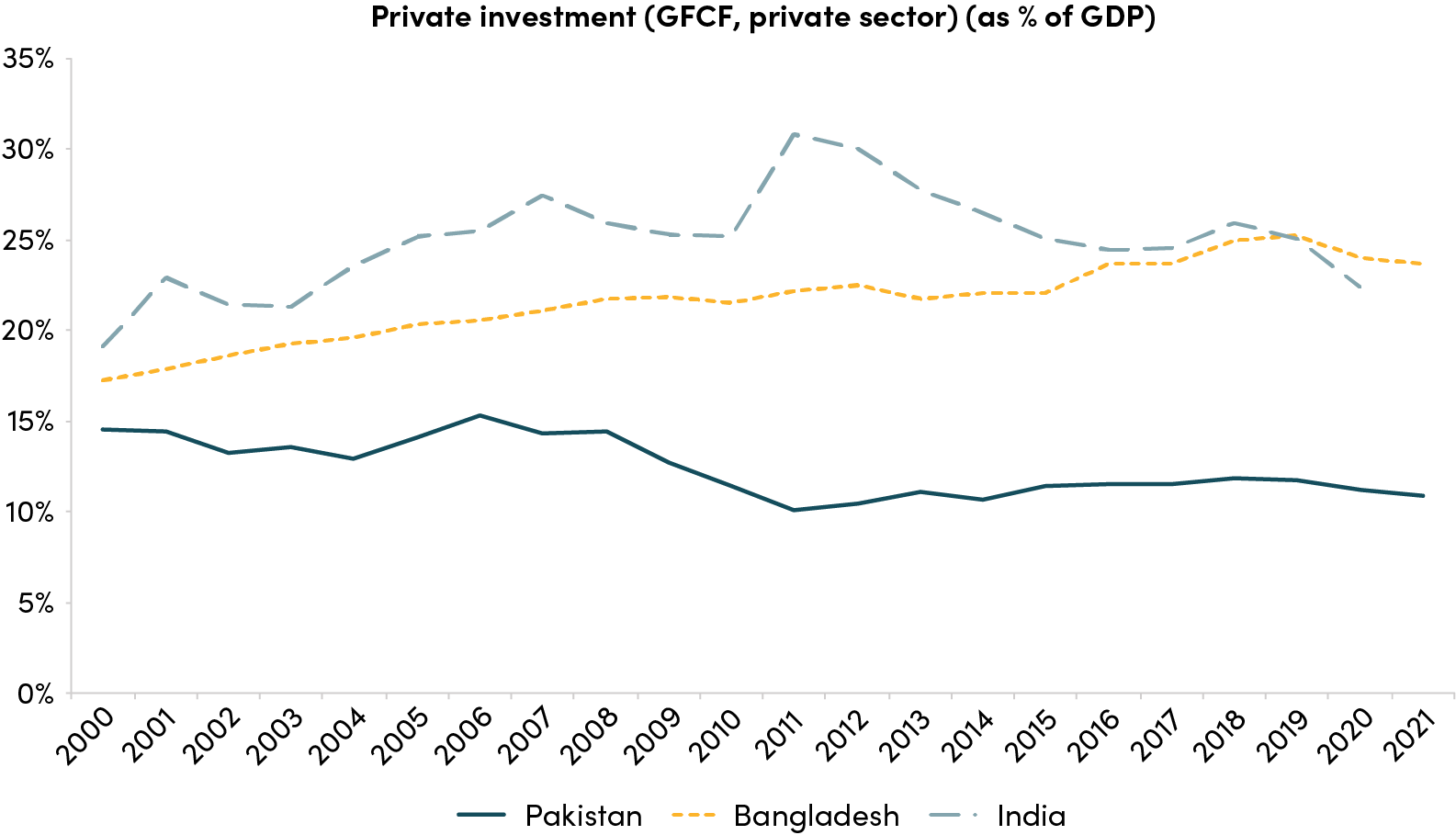

Pakistan’s downward drift is evident in its frequent balance of payments crises. Since 2000, the country has been bailed out by the IMF five times, with each intervention associated with severe belt tightening. By comparison, India’s last IMF program was in 1993. IMF programs in Pakistan helped build up reserves, moderate exchange rate volatility, and achieve price stability, but the gains were short lived. There was little progress on reforming the economic structure that causes the frequent balance of payments crises, namely weakening exports and strong imports. Between 2000 and 2022, the Pakistani rupee fell from 52 to the US dollar to 220, manufacturing and exports stagnated (Figure 3), investment fell (Figure 4), real wages remained flat, and debt (largely domestic) has spiked. A growing proportion of public resources is now needed for debt servicing, leaving little room for much-needed physical infrastructure, education and health expansion, and climate change preparedness. Pakistan’s enviable record of the steepest reduction in South Asia’s extreme poverty[1] (now in single digits) is under threat.

Figure 3. Pakistan’s export performance is now poorer than in India and Bangladesh

Source: World Development Indicators, World Bank

Figure 4. The share of investment in GDP is stagnant and much lower than in India and Bangladesh

Source: World Development Indicators, World Bank; Economic Survey of India

What needs fixing?

Pakistan’s macro-fiscal problem is not complex technically. The economic management challenge is at two levels. The first—reducing the current account deficit and building up reserves to stabilize the exchange rate, targets of IMF programs—is relatively easy. Because Pakistan’s deficit is government-led, the IMF program creates the enabling environment for cutting back public investment in infrastructure, education, and health, and to implement quick fixes on the revenue side. Stabilization is much harder to achieve when the private sector gets into trouble, as in East Asia in the late 1990s, because of the legal challenges to cleaning up bank balance sheets.

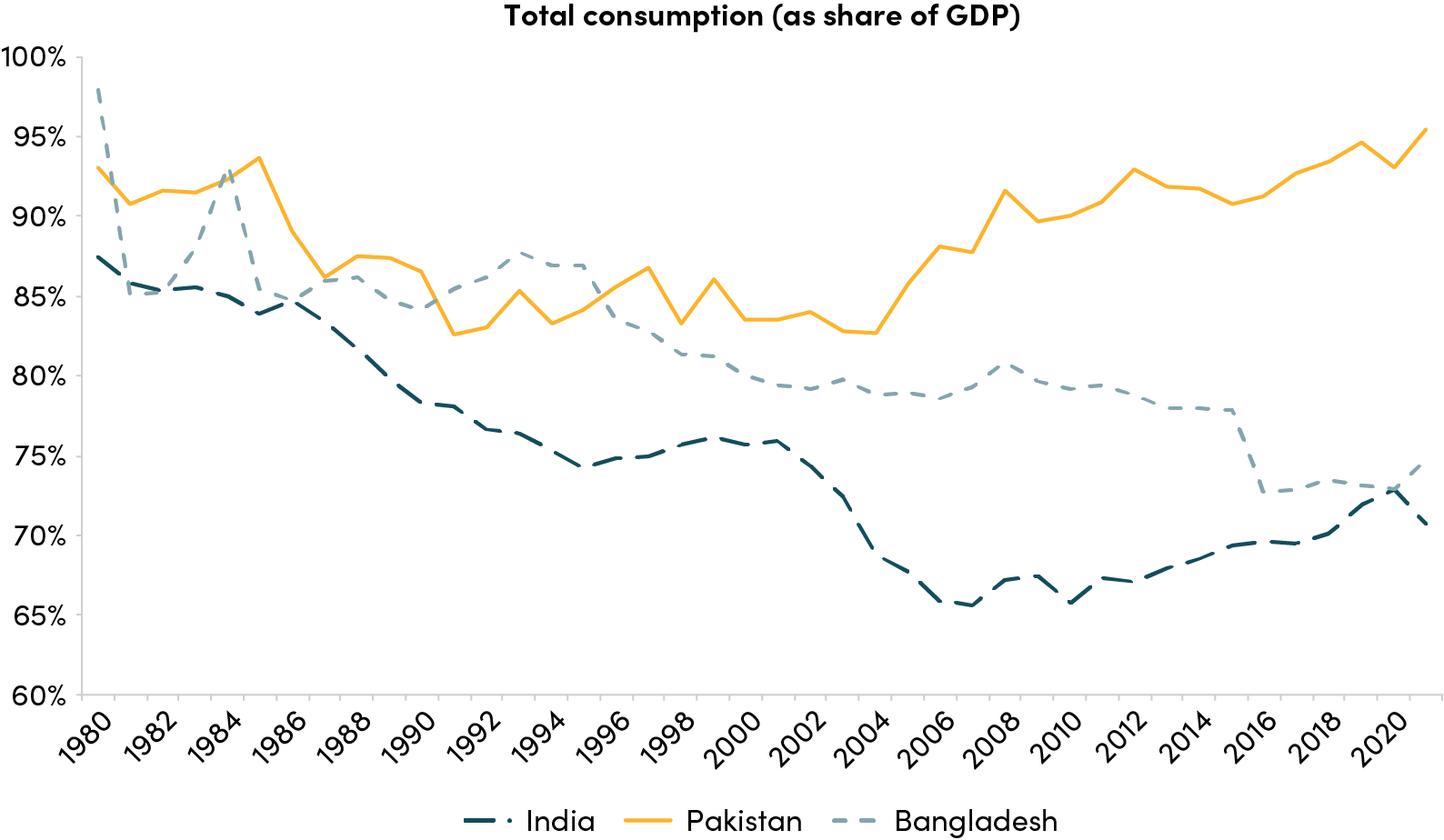

At the structural level, fixing the causes of frequent spikes in the current account deficit is more challenging. This requires addressing the twin deficits in the trade and fiscal accounts. Pakistan’s persistent trade deficit reflects stagnant manufacturing and poor export competitiveness due to low investment and modest technological innovation caused, in turn, by an unfavorable regulatory environment, frequent power outages, poor logistics, and political uncertainty. Large inflows of remittances (Pakistani workers abroad send nearly $30 billion annually—10 percent of GDP[2]), meanwhile, have sustained overvaluation of the rupee for long periods, skewing relative prices in favor of imports. This, combined with high population growth and low taxes on wholesale and retail trade, has led to a consumption boom[3] (Figure 5) and rapid growth of imports[4]. Remittances have also fueled the largely unregulated and undertaxed real estate sector, trapping savings in land speculation that promises higher return than manufacturing exports.

Figure 5. The share of consumption in GDP is much higher in Pakistan than in India and Bangladesh

Source: World Development Indicators, World Bank

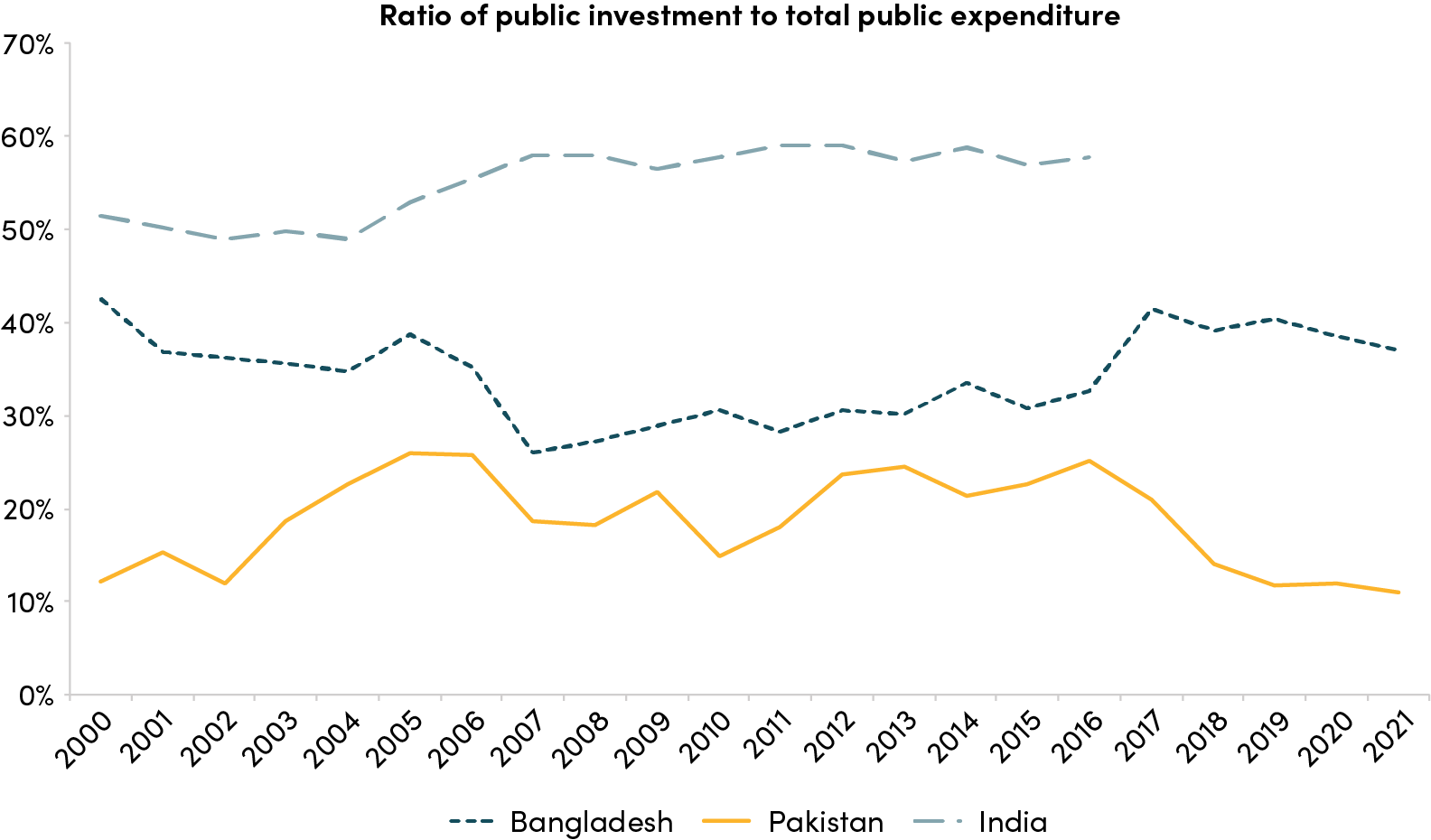

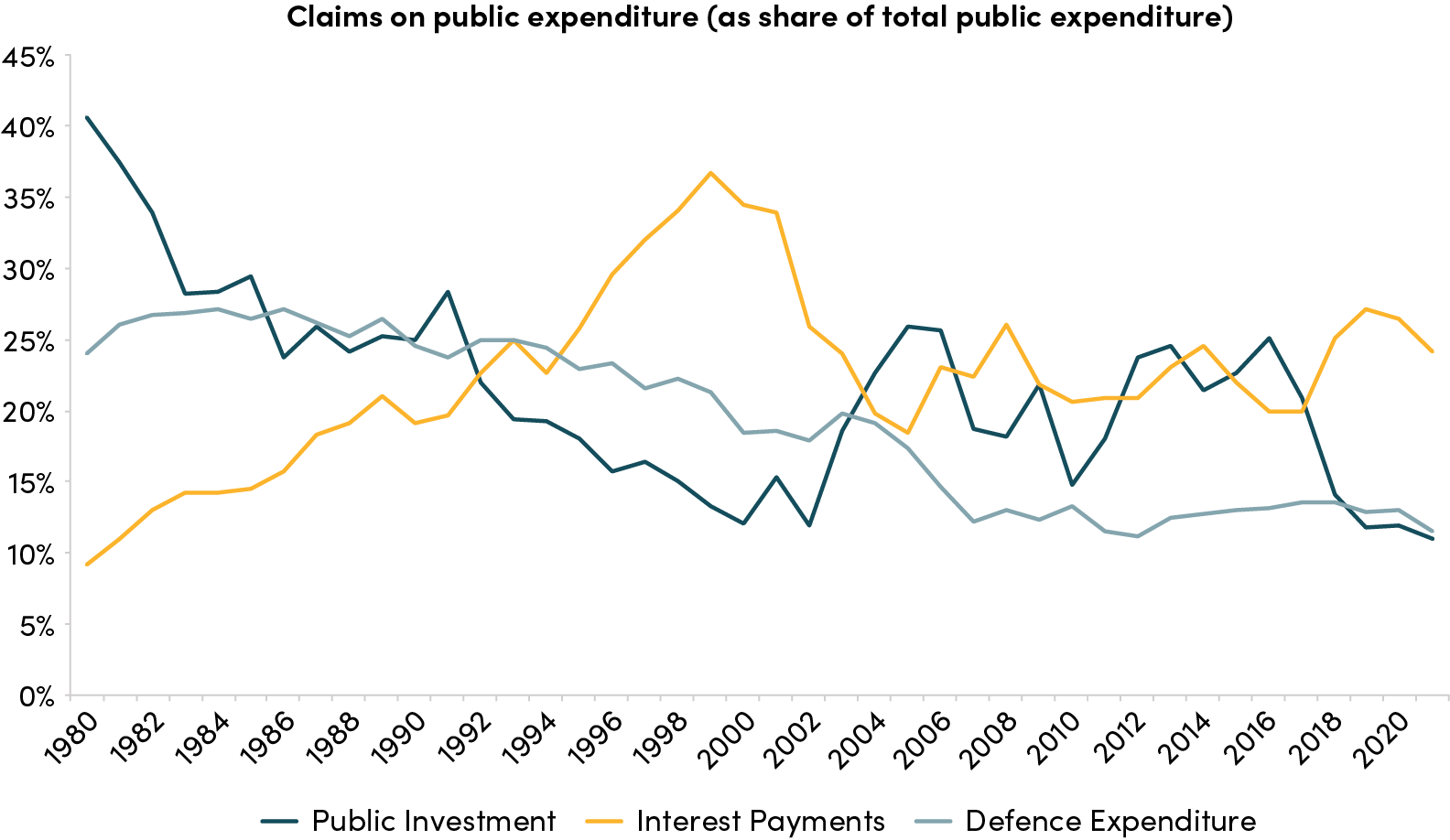

Correcting the persistent fiscal deficit requires addressing long-recognized fragilities in public expenditure management and revenue collection. On public expenditure (Figures 6 and 7), correcting the poorly targeted subsidies would be a good start. The energy subsidy is the chunkiest. As currently structured, the subsidy to residential consumers is larger than to industry. Among residential consumers, the subsidy is larger to richer consumers. In industry, a disproportionately greater subsidy goes to firms producing for domestic consumption than for exports. On the revenue side, the low taxes on agriculture and retail and wholesale trade compared to manufacturing needs to be corrected. Investors’ sectoral choices should be based on productivity growth, not tax advantage. It will also help to bring in all individuals who belong in the tax net. It is estimated that only 2 million of the 7 million eligible income tax payers file returns, and many vastly under report their incomes. This is largely because economic activities are treated differently for tax purposes.

The policy framework supporting the suboptimal structure of the economy results in chronic trade and fiscal deficits. But it generates huge rents for the country’s powerful elite, which is heavily vested in real estate, retail, and low productivity agriculture, and enjoys the lion’s share of subsidies. Sustained structural reform requires an understanding of the political underpinnings.

Figure 6. Public investment, consistently lower than India and Bangladesh’s, has declined further

Source: Pakistan Economic Survey, Bangladesh Economic Survey, Economic Survey of India

Figure 7. Interest payments are crowding out critical public expenditure needs

Source: Pakistan Economic Survey

The political challenge

The suboptimal structure of the economy is lubricated by remittances but is rooted in the windfall concessionary flows associated with Pakistan’s geostrategic location. It is striking that the reversal of economic outcomes coincided with Pakistan’s deepening engagement with the war in Afghanistan. Just when India and Bangladesh were reforming, Pakistan turned into a security state struggling with public safety and other blowbacks of the war. Large volumes of concessionary capital associated with the war fueled an expansion of public expenditure but without Pakistan effectively modernizing its governance to ensure that the expenditure was accounted for and productive. Moreover, despite the conditionality associated with concessionary capital flows, Pakistan did not pursue tax evasion with vigor, paying only lip service to the abundant technical advice it received on modernizing the tax base. The poor security environment made it attractive to park rents in real estate rather than in upgrading manufacturing, never mind the plethora of technical advice by donors to improve the investment climate.

Military governments can be harbingers of economic reform, as in the 1960s in Pakistan and Korea. Indeed, Pakistan’s last military government (1999-2008) was launched with a flurry of reform. The massive inflow of concessionary capital following 9/11, however, created a big gap between the policy prescription negotiated to secure donor funds and its implementation. Thus the transition to democracy in 2008, after nearly a decade of military rule, had a price tag beyond the country’s reach. In 2006-07, international commodity prices (including the price of oil) shot up and General Musharraf, Pakistan’s leader at the time, decided not to pass on the higher prices, especially to consumers of petroleum products and electricity, in the hope of securing more time in office for his government. This disastrous move, contrary to the announced reform, resulted in a huge subsidy which was not backed by government saving. It did not secure Musharraf’s government but left a complex legacy of large fiscal deficits for the subsequent elected governments.

The powerful beneficiaries of the suboptimal economic structure have a strong hold on the media, which chooses to ignore the trade-off between the short-term cost and long-term benefits of reform. Reform of the energy subsidy, for example, is spun by popular television anchors as hurting the poor and raising industry input cost. There is little discussion of targeting subsidies to protect low-income households and exporting firms. Thus, no political party has chosen to spend political capital pursuing deeper structural reform because each faces an election soon after IMF-assisted stabilization—and cutting the roots of rent seeking requires tackling large swaths of powerful election influencers who benefit from it. Despite the availability of rich tax and subsidy data (thanks to multilateral technical assistance), there is a surprising reluctance to use data analytics to inform the public of the winners and losers of reform.

Structural reform requires sustained effort and focused policy energy to tackle the powerful lobbies vested in the old structures. India reformed despite weak coalitions and election reversals because political parties that disagreed on many things tacitly agreed that the IMF program negotiated in 1992 would be the last one—and without economic security, India would not be taken seriously by the world. Bangladesh’s political infighting was resolved with the weakening of Khalida Zia and the emergence of Sheikh Hasina’s Awami league, which developed an economic vision and harnessed technocrats and NGOs to realize it.

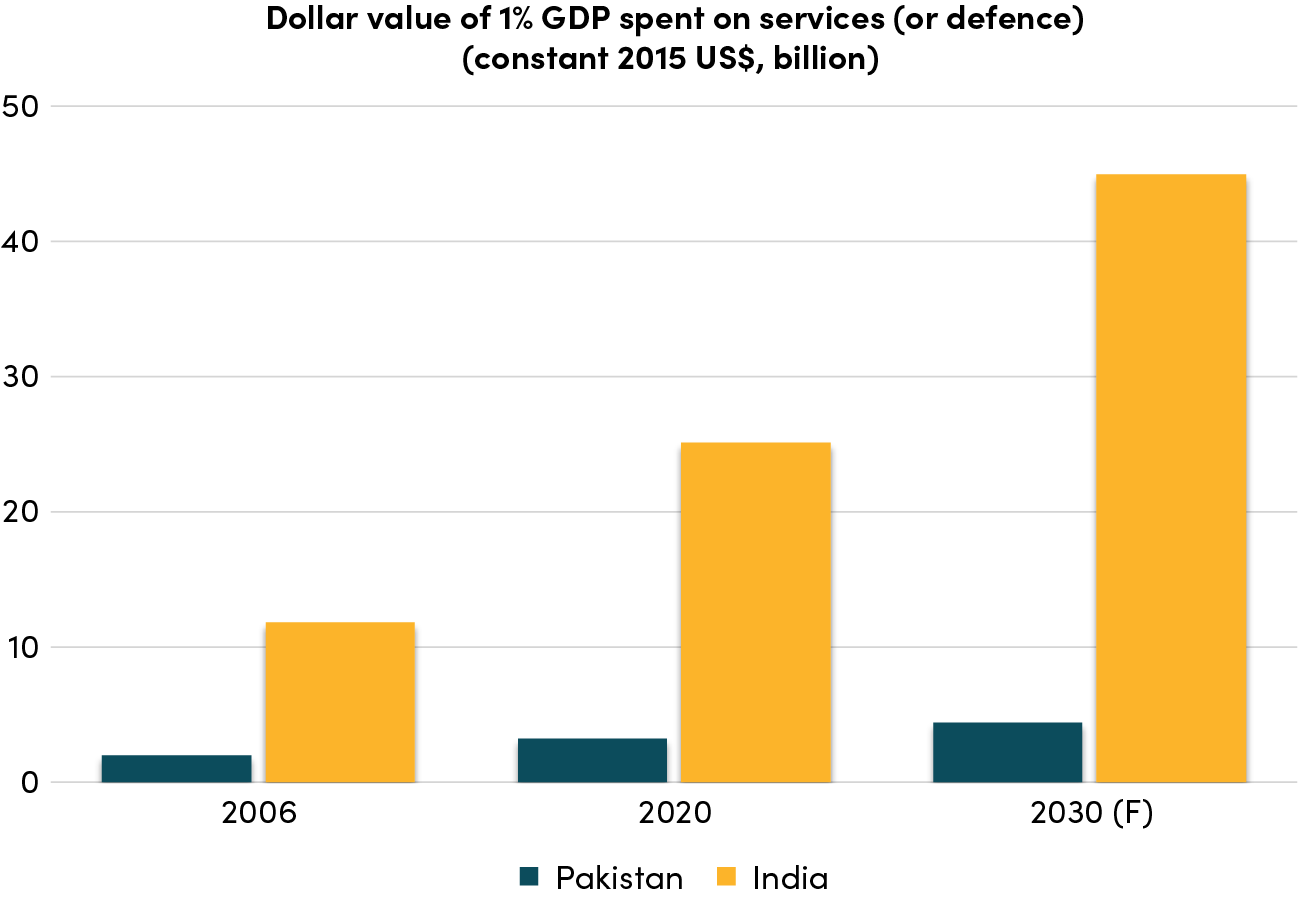

There is a widespread perception that when Pakistan transitioned from a military government in 2008, it moved to a “guided” democracy without a clear vision for economic reform. The only certainty in this dispensation is the five-year election cycle—and the heavy presence of the “guide”(a euphemism for the security establishment). Given the security establishment’s concerns about regional security, it should worry about the sustained economic downturn and commit itself to fixing the economy. In 2000, 1 percent of GDP fetched US$ 1.5 billion and $8 billion[5] (ratio of 1:5) worth of military equipment in Pakistan and India respectively. In 2021, it fetched $3.4 billion and $27 billion (a ratio of 1:8) (Figure 8). National security clearly requires that economic turnaround be a necessary condition for an elected government’s longevity. And yet, two prime ministers were dismissed on contested charges of corruption and the third via a controversial and “guided” vote of confidence despite the successful management of COVID and gathering evidence of economic recovery[6]. Poor economic management clearly was not the primary reason for the dismissal of elected prime ministers. Furthermore, aborting governments before they complete their term has resulted in a culture of horse trading of parliamentarians and a “shadow” power play. It has promoted extreme rhetoric in public discourse and bitter political infighting, making it impossible to arrive at a consensus on reform. Coping with the vulnerability to intervention by the ”guide” results in instability of democratically elected governments and the related dissipation of policy energy to carry out the needed reform.

Figure 8. Consistently lower economic growth, compared to India, contributes to increasing security expenditure disparity

Source: World Bank World Development Indicators, Author’s calculations

The way forward

To make sustained progress towards economic recovery, there is a need to:

-

Strike an agreement among major political parties on uninterrupted core structural reform of the economy. Reforms should include:

-

adopting a prudent fiscal stance by making public expenditure more productive and equitable, especially energy and public enterprise subsidies; implementing a non-discriminating tax regime across individuals and economic activity; correcting misallocation of expenditure and revenue between the federal and provincial governments following the 18th amendment; addressing the growing burden of domestic debt; and ensuring compliance with the Fiscal Restraint and Debt Limitation Act

-

ensuring a manageable trade deficit by adopting productivity-enhancing technology to make domestic production more competitive, and attracting much higher than current levels of investment in exports

-

enacting a supportive institutional, regulatory and monetary policy stance, including a market determined exchange rate

-

-

Step back from the ongoing highly charged political confrontation between the leading political parties to reach a cross-party agreement on the core structural reform; there are lessons to be learned from the Indian experience on scaling back political discord to allow a reform consensus to emerge.

-

Take a three-pronged stakeholder management approach:

-

incentivize the powerful elites who currently enjoy huge rents to switch to investment patterns consistent with the new structure of the economy by maintaining a consistent policy framework and eschewing any backdoor deals that slip in exemptions and thus deviate/distort from the framework; recognize achievements and give social status to exporters and large tax payers

-

engage with the judiciary so that legal challenges to the structural shift are met successfully

-

strengthen data analytics capabilities to conduct an informed public debate on the needed change

-

-

The national security framework recognizes the critical importance of putting the economy on the path of sustainable growth, and that muddling along with frequent balance of payments crises has eroded Pakistan’s standing in the world, making it harder to protect national interests. Accordingly, Pakistan should set up, as part of the national security framework, a formal review mechanism to ensure that key reform milestones are being met and that progress on these would be a necessary condition for government’s longevity.

-

Negotiate with multilateral development banks that a country committed to the first three requirements must have the fiscal space to stay the course on protecting the poor and sustaining a robust public investment program to support growth, create jobs for the rapidly growing population and prepare for the fallout of global warming.

References

Husain, Aasim: “Finding the Right Balance”, Insights for Change, Consortium for Development Policy Research (CDPR), February, 2022. https://cdpr.org.pk/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Finding-the-Right-Balance.pdf

Main, Atif: “A Conversation on Pakistan’s Economy”, Princeton University, April 15, 2022. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VXNL0VX-8eo

Nabi, Ijaz: Economic Growth and Structural Change in South Asia: Miracle or Mirage, Development Policy Research Center Monograph, Lahore University of Management Sciences. March 2010.

Nasim, Anjum and Ijaz Nabi: Addressing Pakistan’s Chronic Fiscal Deficit, CDPR and IDEAS Working Draft, April 2021.

World Bank, Pakistan Development Update: Reviving Exports, October 2021. https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/4fe3cf6ba63e2d9af67a7890d018a59b-0310062021/original/PDU-Oct-2021-Final-Public.pdf

Yusuf, Shahid, “Is Pakistan a Normal Economy”, Insights for Change, Consortium for Development Policy Research (CDPR), June, 2022. ”https://cdpr.org.pk/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Is-Pakistan-a-Normal-Economy.pdf

Comments by Masood Ahmed (president, CGD) and Shahid Yusuf (non-resident fellow, CGD) on an earlier draft are gratefully acknowledged. Bilal Ayaz Butt (CDPR) provided valuable assistance with the graphs.

[1] World Bank defines extreme poverty in terms of per capita income of US$1.90 a day in 2011 PPP terms.

[2] Low-income households are the primary beneficiaries, therefore remittances are good for income distribution and poverty reduction.

[3] At 95.5 percent, the share of consumption in GDP is the largest and the saving rate the lowest in South Asia

[4] Low agriculture productivity, high population growth and remittances fueled demand has contributed to large increase in food imports.

[5] Constant 2015 US$. World Development Indicators

[6] Since the return to democracy in 2008, no prime minister has lasted more than about 3 years, even though the two large parties (PPP; 2008-13 and PMLN; 2013-18) completed their full five-year terms. The PTI (2018-2022) prime minister and government were sent packing in 3.5 years via the first successful vote of no-confidence in the country’s recent parliamentary history. Coping with this vulnerability to intervention by the ”guide” results in instability of democratically elected governments and the related dissipation of policy energy to carry out the needed reform.

Rights & Permissions

You may use and disseminate CGD’s publications under these conditions.