Key Recommendations

Expand liquidity and fiscal space for poor countries. The Biden administration should take immediate action to avert defaults in low-income countries through large and immediate provisions of liquidity and measures to help countries manage rollover risk on sovereign bonds.

Expand official bilateral debt relief to poor countries. The administration should work with the international financial institutions, China, and the Paris Club to implement guiding principles for a COVID-19 common framework for debt treatment.

Reform the sovereign debt system. The Treasury Department should lay the groundwork for a series of updates to the international financial sovereign debt restructuring architecture.

Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, a growing number of poor countries are confronting an impossible fiscal choice between servicing greatly increased sovereign debt or spending more to protect the health, education, and livelihoods of their citizens. Today, nearly half of the world’s poorest countries are at high risk of or experiencing debt distress. Depending on the length of the health crisis and severity of the global economic downturn, many poor countries could find themselves in a full-blown debt crisis over the next few years. While the world has recently grappled with several high-profile restructurings from Greece to Argentina, the international community is now confronted with the prospect of synchronized debt crises across dozens of countries.

Swift and orderly action on international debt is a moral, political, economic, and security imperative for the United States. A series of disorderly and protracted debt crises would be catastrophic for the world’s poorest countries. It would add significantly to the damage already wrought by the pandemic, reversing decades of development gains, throwing millions into poverty, and leading to years of lost growth. It would also be costly for the international community and international financial institutions (IFIs), whose shareholders would end up footing a big portion of the bill for collapsing economies. It would amplify political instability, anti-democratic forces, and the risk of conflict in already fragile poor countries, with potential long-run security consequences for the United States.

The international community’s response to the COVID-19 challenges facing low-income countries has fallen far short, reflecting in part a lack of ambition and in part deep divisions between the leading economies. The G20’s actions to date have not been commensurate with the financing needs of poor countries; and the failure to launch sizeable liquidity programs for poor countries could exacerbate the breadth and severity of future debt crises. In some instances, the United States has stood in the way of larger, more ambitious measures—such as a large IMF Special Drawing Rights (SDR) allocation, which would bolster countries’ foreign exchange reserves at no cost to shareholders.[1] In other cases, it has been unable to reach agreement with China—the largest single creditor to many developing countries—on offering debt relief on its loans on the same terms as other official creditors.

A Biden administration can raise the G20’s ambition level to avert a global debt crisis and strive to forge a consensus around a COVID-19 debt framework. The United States can also encourage the international community to take a longer-term view of the crisis and press for deep systemic reforms to the broader architecture for sovereign debt. This will require robust consultation with the Paris Club and China; a coordinated stance toward private creditors; and close cooperation with the leadership of the IFIs, especially the IMF and World Bank.

Immediately, the Biden administration will need to take actions to enhance access to liquidity for low-income countries and lower-middle-income countries to avert a full-blown debt crisis. This could be done through some combination of an IMF SDR allocation and an extension of the Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI). For countries in need of debt relief, the US should seek to implement the G20 agreement on a debt relief common framework whereby all bilateral creditors participate in debt restructurings on comparable terms and in full transparency. In parallel, the US should seek to secure more profound reforms to sovereign debt restructuring system.

Debt relief for poor countries: What’s broken?

Low- and lower-income countries entered the COVID-19 crisis with preexisting serious external vulnerabilities that have only been exacerbated by the global economic downturn. The World Bank projects that their external financing needs stand at around of 9.2 percent of GDP ($179 billion) in 2020 and will hover around 7 percent in 2021, of which 30 percent is driven by bilateral debt due.[2]

Box 1. Debt Service Suspension Initiative Refresher

In April 2020, the World Bank’s Development Committee and the G20 Finance Ministers endorsed the Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI) to help the poorest countries manage the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Under the initiative, G20 bilateral creditors agreed to postpone debt payments from the poorest countries (73 countries eligible for IDA assistance and Angola) that request the suspension.

When the initiative ends, currently slated for June 2021, countries will have to repay the deferred principal and interest over four years following a one-year grace period.

Private creditor participation is voluntary and the G20 has encouraged them to participate in the initiative on equal terms.

To prevent a series of disorderly defaults and give countries breathing room to mount a health and economic crisis response, in April 2020 the G20 launched the DSSI, allowing eligible countries to suspend their debt service to G20 countries—and, theoretically, the private sector—through mid-2021 (see box 1). But the initiative faces several limitations. Private creditors, which constitute close to 20 percent of DSSI debt service in 2020, have declined to participate. Several countries that have requested DSSI treatment have been downgraded by the rating agencies, which they paradoxically interpreted as a step towards default. As a result, few DSSI eligible countries—and not a single sub-Saharan African country—have issued international bonds since March, at a time when they badly need financing and global interest rates hover near record lows. Finally, China—the largest single creditor to DSSI countries—has largely exempted its government-owned lenders from the initiative, claiming they are private sector entities.

To date, 46 out of 73 eligible countries have applied for DSSI treatment. As a result, only $5.7 billion is likely to be suspended this year compared to the $11.5 billion anticipated at the outset. These implementation flaws combined with disagreements between G20 countries around the treatment of their loans have blunted the DSSI’s effectiveness. But they also expose profound weaknesses in the underlying international architecture for resolving sovereign debt.

If exceptional financing materializes through the IMF and MDB system, alongside the DSSI treatment, many DSSI countries may be able to weather the crisis without the need for debt reduction. But if recovery stalls in 2021 or beyond, several countries could see their debt levels rise to unstainable levels that would require varying levels of debt relief to restore sustainability. Mounting a debt relief initiative where all creditors agree to the same terms is, therefore, critical. In November, the G20 agreed on a Common Framework for Debt Treatments beyond the DSSI, based on Paris Club terms that calls for debt restructuring negotiations if warranted by IMF debt sustainability analyses. But if the DSSI experience is precedent, implementing such an initiative will require more extensive levels of international cooperation, compromise, and goodwill. The G20 will need to agree on a definition of bilateral debt that does not give official creditors leeway to exclude some government entities from participating. And the G20 will need to deploy significantly more pressure on the private sector to join or they risk ignoring the initiative entirely. To date, these issues remain unresolved. The framework does not address which category of Chinese credits will be included and puts the burden on debtor countries to get their private creditors to participate.

Box 2. What is the Paris Club?

The Paris Club is an informal group of representatives from creditor nations whose objective is to find workable solutions to payment problems faced by debtor nations. The Paris Club has 19 permanent members, including most of the western European and Scandinavian nations, the United States, the United Kingdom, and Japan.

In its negotiations with debtor countries, the Paris Club operates in accordance with six principles:

Case by case: The Paris Club makes decisions on a case-by-case basis in order to tailor its action to each debtor country's individual situation.

Comparability of treatment: A debtor country that signs an agreement with the Paris Club agrees to seek comparable terms from all bilateral creditors, including non-Paris Club commercial and official creditors.

Conditionality: Agreements with debtor countries will be based on IMF reform programs that help ensure the sustainability of future debt servicing.

Consensus: Paris Club decisions cannot be taken without a consensus among the participating creditor countries.

Information sharing: Members will share views and data on their claims on a reciprocal basis.

Solidarity: All members of the Paris Club agree to act as a group in their dealings with a given debtor country.

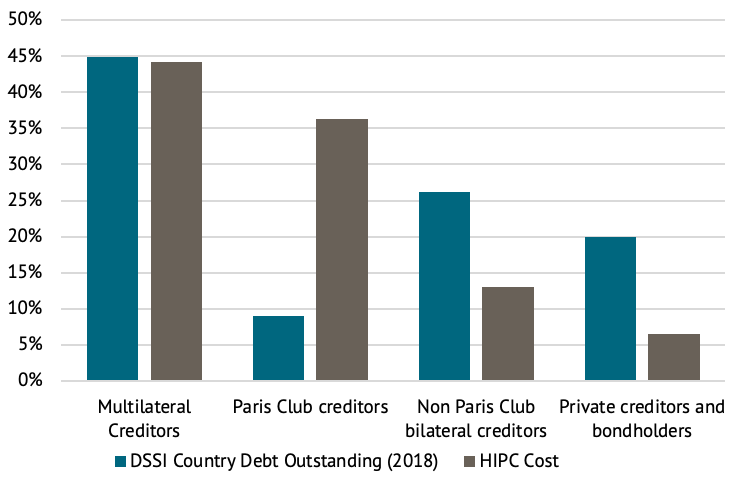

The rise in non-Paris Club creditors makes navigating today’s looming debt crises more complex. Over the last decade, low-income countries and lower-middle-income countries have diversified their sources of external finance. China has emerged as a top lender, rivaling only the World Bank. And many poor countries enjoy access to bond markets and loans from private creditors. While the Paris Club has historically been the key forum for coordinating debt restructurings, China has eschewed participation, instead preferring to renegotiate its loans bilaterally and often secretly. This approach would not be beneficial for countries in debt distress since piecemeal restructurings often kick larger sustainability issues down the road. For many decades, the Paris Club was able set norms and principles—namely comparability of treatment and transparency—for sovereign restructurings, which it was able to impose by virtue of the size of the creditors it represented. So while the international community was able to find workable solutions to the last round of low-income country debt crises with the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) and Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative (MDRI), the relative homogeneity of the low-income country creditor base made it possible to anchor HIPC in Paris Club principles without having to seek consensus across an unwieldy cast of creditors.

Against this backdrop, the lack of debt transparency—both on the creditor and debtor side—has become a major issue. Much officials bilateral, including China, and private creditor lending has often been opaque, failing to disclose amounts, terms, and conditions. And the rise in state-owned enterprise borrowing combined with poor debt management capacity means that many governments do not systematically track, report, or even entirely know the full gamut of their external liabilities.

Figure 1. The changing sovereign debt landscape: Comparing DSSI country debt stock with HIPC costs by creditor category (%)

Source: IMF HIPC Statistical Update 2019, World Bank International Debt Statistics, CGD staff calculations.

Looking beyond the current crisis, deeper reforms to the international sovereign debt architecture are needed. The IMF’s proposal in 2003 for a Sovereign Debt Restructuring Mechanism was the closest the international community has come to developing a governance solution for sovereign debt restructurings.[3] The proposal included a plan to establish an international Dispute Resolution Forum with jurisdiction over all disputes between parties. Under the mechanism, a sovereign facing an unsustainable debt burden could request a stay on creditor enforcement that would last throughout the duration of a restructuring agreement. The Sovereign Debt Restructuring Mechanism would allow a majority of creditors—across asset classes—to agree on the terms of a restructuring framework that would be binding.

Ultimately this proposal was jettisoned because key shareholders, especially the US, under pressure from private financial actors, were reluctant to appear to abdicate sovereignty to the IMF. Instead, the IMF and international community opted to pursue a contractual route and launched the Collective Action Clauses (CACs). CACs are legal provisions in bonds, requiring that a majority of bondholders agree to the terms of a restructuring. Where bonds include CACs, they have largely been successful in prohibiting holdouts from blocking a restructuring. And they have made recent sovereign debt restructurings more preemptive, shorter, and achieve higher creditor participation.[4] It is important to note, however, that a substantial portion of poor country sovereign debt is in the form of direct loans from private creditors and that these loan contracts have no such provision to encourage collective action across creditors.

But the contractual approach has its limitations and increasingly countries are seeking to implement legal limits on actions that holdout creditors can take on defaulting countries. In 2010, the UK Parliament passed the Debt Relief (Developing Countries) Act, which imposed a cap on the amount a litigious creditor could recover from claims on a HIPC country debt or the execution of a foreign judgment within the UK.[5] France and Belgium have more recently passed similar legislation.

Policy Recommendations

The Biden administration should take immediate action to avert defaults in low-income countries through large and immediate provisions of liquidity and measures to help countries manage rollover risk on sovereign bonds. In parallel, the administration should work with the IFIs, China, and the Paris Club to agree on broad principles for an eventual COVID-19 debt relief initiative. At the same time, the Treasury Department should lay the groundwork for a series of updates to the international financial sovereign debt restructuring architecture.

Expanding liquidity and fiscal space for poor countries

As a first step, the US Treasury Department should approve a 500 billion IMF SDR allocation. This can be done immediately and does not require congressional authorization. The Treasury Department should also work with Congress to authorize at least an additional 500 billion SDR allocation depending on global liquidity conditions. Neither of these moves would have a cost for the US taxpayer.

In addition, the Treasury Department should request funding to help cover the cost of IMF debt service relief and a scale-up in funding for poor countries. Treasury should request at least $1 billion in appropriations for the IMF Catastrophe Containment and Relief Trust and Poverty Reduction and Growth Trust.

The Treasury Department should work with G20 counterparts to reach agreement on a collective call for MDBs to double their pre-COVID-19 outstanding exposures to over $1 trillion over the next five years, with a particular focus on poor countries. Meeting this commitment will involve adjusting overly conservative lending policies that undercount MDB callable capital. It will require concerted transparency on MDB commitments and disbursements to make it possible to track implementation of the agreement. It will require early consideration of the capital adequacy of the MDBs with a view toward assessing whether additional capital is needed to extend higher levels of lending over time. For IDA concessional resources and other concessional windows of the MDBs, donors should launch early consultations or supplemental replenishments.

Finally, in coordination with the MDBs, the Treasury should advocate for an MDB green sovereign debt guarantee scheme to help countries maintain market access and set the stage for a green recovery. Under this initiative, one or several MDBs could guarantee sovereign bond issuances to help countries manage rollover risk on existing external private sector debt and maintain market access over the longer term. To ensure that these publicly funded guarantees offer benefits to poor and vulnerable populations, they could be earmarked for green or SDG bond issuances.

COVID-19 official bilateral debt relief

The Treasury Department and the White House should press for a further extension of the DSSI at least through the end of 2021. This will require Treasury and the White House persuading G20 partner countries that a longer suspension is in their interest. An extension could be approved at the first G20 Finance Ministers meeting under the Italian presidency.

The US Treasury and the White House should press for the implementation of the Common Framework for Debt Treatments based on the principles of comparable treatment between creditors, transparency, and full creditor participation. Under this initiative, countries with unsustainable debt burdens would be eligible for reschedulings or write-offs based on an IMF-World Bank Debt Sustainability Analysis that would determine how much debt forgiveness the country needs to achieve sustainability.

For US official credits, depending on the amount of countries that need relief and how much they require, Treasury may need to work with the Office of Management and Budget, other relevant agencies such as Ex-Im, and Congress to appropriate funding for relief. The total debt stock outstanding that countries at high risk of distress owed the United States stood at $433 million in 2018. It is unlikely that all countries at high risk will require relief or that they will need full forgiveness, so the ultimate number would likely be a small fraction of the total.

Build back a better sovereign debt architecture

Treasury should develop and propose “new rules of the road” to guide lending to lower-income countries. With an eye to avoiding future unsustainable debt build-ups in poor countries, Treasury should seek to achieve consensus between G20 countries, the IFIs, and private creditors around sustainable and responsible lending practices.

A key aspect of rule-writing should be standards for transparency and disclosure that hold both debtors and creditors accountable, allow accurate debt sustainability assessments, and promote better debt management. Bilateral and private creditors should agree to make public their loans, including details about terms and conditions. In parallel, Treasury should advance a plan with the IFIs, regulators, legal authorities, and private finance representatives to link the enforceability of bond and loan contracts to formal, documented approval by the relevant public authorities of sovereign borrowing, and to public access to such documents.

The Treasury Department and the White House should also take steps to enhance private sector creditor participation in future standstills and restructurings. To do this, the White House, along with the Treasury and the Department of Justice should explore the feasibility of passing legislation to modify US sovereign immunity law so that the private sector creditors cannot initiate litigation against countries whose debt the IMF deems to be unsustainable due to global systemic crises or natural disasters, at least throughout the duration of their restructuring negotiations.

In addition, Treasury should work with G20 counterparts, the IMF, private creditors rating agencies, and regulators, to develop and adopt new bond and loan contract issuance standards that would include a provision to permit temporary suspension of debt service to both private and public creditors without triggering a default in crisis situations. Such provisions could be activated in the event of an IMF determination in the context of a global or regional crisis, unrelated to a country’s policies, that debt service to all creditors would demonstrably and materially push a country toward an unsustainable debt situation.

Finally, in cases of country insolvency, Treasury should work with other IMF shareholders to avoid bailouts of private creditors by the IMF and IFIs. Where countries’ debt situations are unsustainable based on IMF analysis, it is essential to strike a fair and equitable balance between new taxpayer money and private creditor contributions to debt resolution. Such a balance has not always been struck as the IMF has often come forward with new financing before it is clear how much private creditors will contribute to the return to debt sustainability. Going forward the United States and other IMF shareholders should work out a process of explicitly tying IMF disbursements at appropriate points and of appropriate sizes to a certain threshold of private creditor participation in negotiated restructurings. Private creditors would have to decide if their repayment prospects are made better or worse by accepting a deal supported by IMF financing.

Additional reading

Lee Buchheit and Sean Hagan, From Coronavirus to Sovereign Debt Crisis, Financial Times, March 2020.

Group of 30 Working Group on Sovereign Debt and COVID-19, 2020. Sovereign Debt and Financing for Recovery after the COVID-19 Shock: Preliminary Report and Recommendations.

International Monetary Fund, 2020. The International Architecture for Resolving Sovereign Debt Involving Private-Sector Creditors – Recent Developments, Challenges and Reform Options, IMF Policy Paper 2020/043.

Nancy Lee, 2020. Debt Relief for Poor Countries, Three Ideas Whose Time Has Come, CGD Blog, Center for Global Development.

Clemence Landers, 2020. Addressing Private Sector Debt through Sustainable Bond Guarantees, CGD Blog, Center for Global Development.

Mark Plant, 2020. Making the IMF’s Special Drawing Rights Work for COVID-19 Economic Relief, CGD Note, Center for Global Development.

[1] Nancy Birdsall, New SDRs? That Pesky 85 Percent Approval, CGD Blog, Center for Global Development.

[2] Joint IMF-WBG Staff Note: Implementation and Extension of the Debt Service Suspension Initiative, October 2020

[3] Anne Krueger, A New Approach to Sovereign Debt Restructuring, IMF, 2002

[4] IMF, The International Architecture for Resolving Sovereign Debt Involving Private-Sector Creditors – Recent Developments, Challenges and Reform Options, September 2020

[5] UK Debt Relief (Developing Countries) Act 2010, (S.I. 2011/1336).

Rights & Permissions

You may use and disseminate CGD’s publications under these conditions.