Recommended

As the rest of the developing world has reaped the benefits of rapid globalisation, Africa has remained marginalised in international trade. The new European Commission has an opportunity to accelerate export-led growth on the continent by introducing a bolder, more coherent policy on trade, agriculture, and aid. To do so, the new Commission should

- work towards ending tariffs on imports from Africa and reform rules of origin to permit increased cumulation;

- improve the effectiveness and impact of EU “Aid for Trade” in Africa by piloting “payment by results”;

- reduce subsidies to Europe’s agricultural sector to help even the playing field with African producers;

- reform the European Globalisation Adjustment Fund to ensure the EU can manage structural adjustment resulting from increased intercontinental trade.

The Challenge

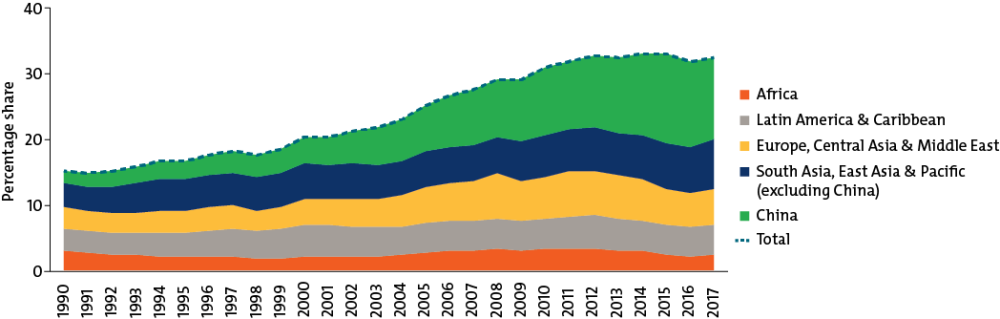

In the past 30 years, while China experienced trade-led growth that lifted some 850 million people out of poverty, Africa’s exports have remained below 3 percent of global trade (figure 1) and been dominated by low value-added commodities (figure 2).[1] The continent’s poor trade performance is both a consequence and a cause of its persistent underdevelopment. Growth remains volatile, quality jobs are scarce, and productivity lags far behind other regions.[2]

Worryingly, a confluence of structural trends looks likely to increase the challenge of achieving inclusive, export-led growth in Africa. “Slowbalisation”—the decline in cross-border trade and investment that followed the 2008 financial crisis—is closing off opportunities for integration in the global economy, Asia’s continuing dominance of manufactures markets is discouraging entry by newcomers, and automation may reduce the labour-absorbing potential of manufactures trade.[3]

Figure 1. Africa’s share of global exports has remained under 3 percent since 1990

Developing economies’ share of global merchandise exports, 1990-2017

Source: UN Comtrade Database: https://comtrade.un.org.

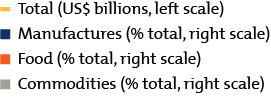

Against this bleak outlook, the recently ratified African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) has raised hopes of stimulating value-added trade in the region. The AfCFTA aims to create a single African market for goods and services, thereby paving the way for a continental customs union. Since value-added manufactures make up a much larger share of Africa’s intra-regional exports than its international ones (see figure 3), removing barriers to this trade is predicted to accelerate industrialisation, employment generation, and export-led growth.[4]

Still, if the AfCFTA is to live up to expectations, African countries must address three major challenges which resonate with those of the EU’s own single market.

The first is non-tariff barriers. The average applied tariff in Africa is 8.7 percent, but other obstacles increase the cost of Africa’s trade by an estimated 283 percent.[5] While the AfCFTA will include provisions on non-tariff measures, these have yet to be agreed and will likely prove challenging, both technically and politically, to negotiate and implement. Yet, if non-tariff barriers are not addressed, then the impacts of the AfCFTA on African countries are estimated to be small and uneven.[6]

A second issue is managing the structural adjustments that will accompany any meaningful liberalisation. The AfCFTA will result in a reallocation of capital and labour to more efficient uses, creating winners and losers within and across countries. Mitigating the costs of this adjustment is essential, since trade agreements with highly unequal benefits tend to unravel.[7] Finally, there is the challenge of finding the capacity, resources, and political will to make progress. The experience of Africa’s Regional Economic Communities, which aim to facilitate integration at the sub-regional level, suggests that these issues will make timely implementation of the AfCFTA difficult.[8]

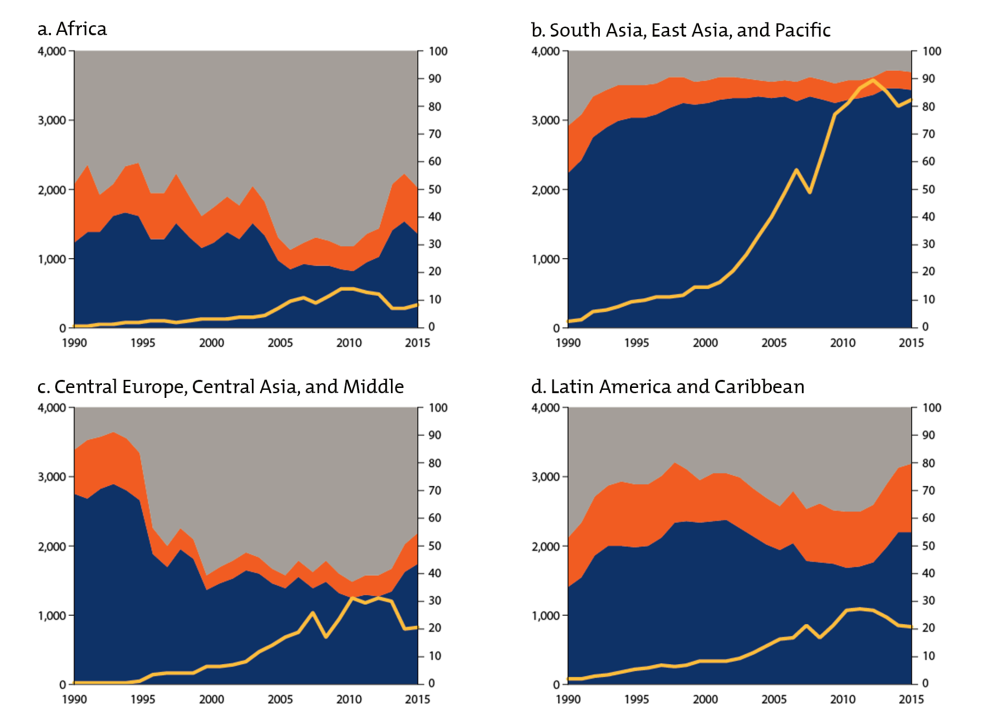

Figure 2. Commodities continue to dominate Africa’s global merchandise exports

Level and composition of global merchandise exports for selected regions (excluding high-income countries)

Source: UN Comtrade Database: https://comtrade.un.org.

Note: Manufactures comprise commodities in Standard International Trade Classification (SITC) sections 5 (chemicals); 6 (basic manufactures); 7 (machinery and transport equipment); and 8 (miscellaneous manufactured goods), excluding division 68 (non-ferrous metals). Food comprises the commodities in SITC sections 0 (food and live animals); 1 (beverages and tobacco); and 4 (animal and vegetable oils and fats) and SITC division 22 (oil seeds, oil nuts, and oil kernels). Commodities comprise SITC section 3 (mineral fuels, lubricants, and related materials); divisions 27 (crude fertiliser, minerals); 28 (metalliferous ores, scrap); and 68 (non-ferrous metals).

The European Union’s Added Value and its Progress to Date

The EU has a key role to play in stimulating export-led industrialisation and growth in Africa. The size of the European market and its relative proximity to Africa mean it should remain an important source of demand for African countries’ value-added trade, particularly if it continues to make progress on liberalising tariff and non-tariff barriers. As the largest providers of investment and Aid-for-Trade (AfT) on the continent, the EU and its Member States should also be key financiers of the AfCFTA and other initiatives to boost intra-African trade.[9] And as the most advanced integration project in the world, the EU should provide a model for Africa as it pursues closer economic union, particularly by demonstrating how market liberalisation can be made compatible with distributional objectives. Below, we assess the EU’s progress in each of these areas.

The EU Market and African Trade

The EU is the largest market for Africa’s trade, accounting for $116 billion (34 percent) of the region’s total exports in 2017 (figure 3). It has also posted the greatest increase in demand for Africa’s higher value-added manufactures: these comprised $42 billion or 37 percent of its total imports from the region in 2017, up from $11 billion or 29 percent in 1997. By contrast, 27 percent of North America’s imports from Africa and just 15 percent of Asia’s are manufactured goods.

There is evidence that the EU’s tariff policies have positively contributed to Africa’s export growth. The EU’s tariff regime for developing countries compares favourably to other advanced economies: when duties are weighted by the income-level of trade partners, only Australia and New Zealand are more open among OECD members.[10] In fact, 52 out of 54 African countries pay low or no tariffs in Europe, either as beneficiaries of the EU’s Generalised Scheme of Preferences (GSP) or under a free trade agreement. Econometric evaluations of the GSP suggest that tariff preferences have increased beneficiaries’ exports to the EU.[11] The impact has been greatest for least developed countries (LDCs), of which 31 are African economies that enjoy full duty- and quota-free access to European markets under the “Everything But Arms” sub-scheme.

Figure 3. The EU is the largest market for African exports

Level and composition of African exports by destination

Source: UN Comtrade Database: https://comtrade.un.org.

Still, the evidence base for EU–Africa free trade agreements is weaker. Since 1997, the EU has concluded agreements with 17 countries in the region, including four Association Agreements with North African countries and five Economic Partnership Agreements with regional groupings of sub-Saharan countries. Ex-post evaluations of these agreements are limited because they have yet to be effectively implemented, however, the ex-ante analysis is concerning. Free trade agreements are expected to have limited impact on African countries’ European exports since most already enjoyed near-full access to the EU under GSP prior to the agreement.[12] Critics further argue that they may hold back the continent’s structural transformation by undermining intra-regional trade and integration.[13] Lowering tariffs on EU imports in African markets is predicted to divert the region’s trade in favour of European producers and away from local or more efficient suppliers. Moreover, because EU free trade agreements have been negotiated with regional blocs rather than the continent as a whole, they have increased the heterogeneity of African countries’ liberalisation commitments, adding to the challenge of rationalising the continent’s trade regimes under AfCFTA. The limited anticipated benefits of free trade agreements explain why many African countries, particularly LDCs, have refused to join them.

Non-tariff barriers may also have dampened the impact of lower duties on African countries’ exports to the EU. The EU’s rules of origin, despite reforms in 2011, are widely critiqued for being overly complex and restrictive,[14] especially rules on minimum domestic content and “cumulation.” To be eligible for reduced tariffs, a developing country export must have a minimum domestic content of 30 percent—a higher threshold than the 25 percent minimum recommended by LDC members of the World Trade Organization (WTO).[15] Moreover, exporters cannot easily “cumulate” inputs from other countries. For example, the 34 African exporters trading under GSP cannot count inputs from elsewhere in the region as domestic content (although they can cumulate with EU members), while the 13 trading under Economic Partnership Agreements, a type of free trade agreement, can only count those from other EPA partners. There is evidence that these restrictions have limited African exporters’ use of tariff preferences and may also have undermined regional value chain creation.[16]

Agricultural subsidies are another non-tariff barrier to African exports. The EU spends around 40 percent of its budget subsidising its agriculture sector.[17] In effect, these subsidies increase EU agricultural supply and, alongside reducing EU demand for imports, lower prices on world markets at the cost of other nations. The EU’s support levels were 18.3 percent of its agricultural farm income in 2017, well above those of Brazil, Canada, China, Russia, and the United States. African agriculture subsidies are much lower: even in South Africa, the wealthiest African country, the figure is just 1.9 percent of output.[18] Moreover, subsidies vary significantly across Member States: while the Netherlands subsidises just 4 percent of its agricultural output, in Ireland this figure is nearly 30 percent.[19] This disparity undermines the Single Market, does little for the environment, and causes damage to development.[20]

EU Aid-for-Trade in Africa

The EU provides substantial amounts of aid to stimulate trade in Africa. While there is evidence that AfT can enhance trade performance, its effectiveness varies considerably across geographies, sectors, and intervention types, and there is a question mark over how well the EU’s scheme is designed.[21] The United Nations Economic Commission for Africa and the African Union have identified three priorities for AfT in Africa: (1) improve the targeting of AfT, particularly by increasing funding to regional programmes with specific integration objectives and to Africa’s poorest countries; (2) ensure coherence and ownership by aligning AfT programmes with African policy frameworks, including AfCFTA and its sister initiatives; and (3) increase the effectiveness and impact of AfT through improved monitoring and reporting.[22]

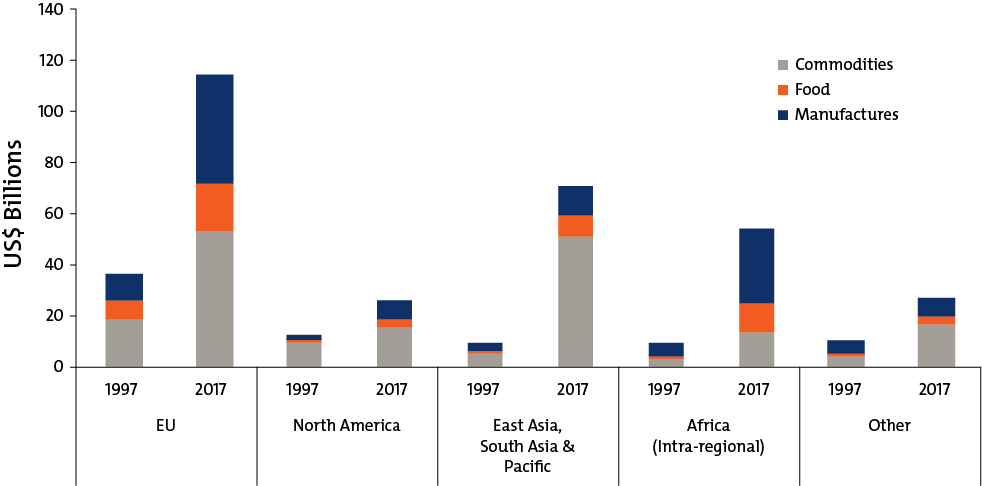

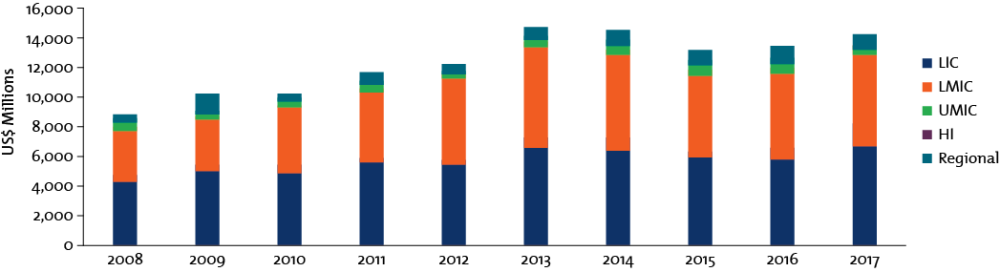

Figure 4. The share of EU Aid for Trade targeting low-income African countries has remained stagnant

Disbursement of EU Aid for Trade in Africa, 2008–2017

Source: OECD Creditor Reporting System.

Evaluating EU AfT against these objectives finds that there is room for improvement. In targeting, while EU AfT disbursements to Africa have increased over the past decade, the proportion allocated to low-income countries has remained roughly constant at 43 to 47 percent (figure 4). Moreover, flows are unevenly distributed across countries, with Morocco, Kenya, Ethiopia, Egypt, Tanzania, and Tunisia receiving nearly half of the total.[23] The share of EU AfT allocated to regional programmes has been consistently low at 10 percent or less. The EU also performs poorly against the coherence objective. A Communication from the Commission recognises AfT spending lacks a coordinating framework: “Current spending of EU’s aid for trade happens in too decentralised and fragmented manner. In 2015 … the EU’s aid for trade represented a third of EU total official development assistance (ODA) and was channelled through some 3,000 financing decisions.”[24] Finally, before 2018, the EU did not aggregate and report on the results of its AfT spending. Its annual “Aid for Trade Review” provided a statistical overview of the portfolio’s geographic and sectoral focus, but no assessment of effectiveness, impact, or lessons learned.

The Commission has worked to address these issues in recent years. In 2017, it released an updated “Aid for Trade Strategy” with objectives that included an increased focus on LDCs, reduced fragmentation, and improved monitoring and reporting.[25] Since 2018, the EU’s annual AfT review has included a qualitative assessment of results across different regions and sectors. Of most relevance to African regional integration, the new Africa-Europe Alliance (see below) commits €50 million in ODA to support implementation of the AfCFTA. Still, ensuring that these funds are successfully deployed to boost intra-African trade will be challenging. Evidence about which AfT interventions work is mixed, and projects that are successful in one context can prove less so in another.[26]

The EU’s Ability to Deal with Structural Adjustment

If Africa and the EU achieve their ambitions on intercontinental trade, it could substantially change the make-up of the industries and economies of both regions. The EU must deal with these disruptions more effectively than, say, the United States did with China. The EU has competence in dealing with the job loss from major trade and structural changes in the form of its European Globalisation Adjustment Fund.[27] The new Commission can reform this still nascent programme to support economic growth and redistribution within the EU, and continue to provide leadership globally on marrying a market and social model. The European Global Adjustment Fund reforms have already improved the design to focus on individuals rather than firms, as is the case in the US equivalent. That programme provides for a visible and economically valuable response to the changes facing workers from trade, economic disruption, and technology that are necessary ingredients of economic growth. Still, the budget and policy design remain unambitious. The annual ceiling on expenditures is just €150 million compared with the EU’s regional policy, which runs to approximately €50 billion per year.[28] In their evaluation, Claeys and Sapir (2018) highlight two major opportunities for the scheme: removing the arbitrary minimum number of workers (500) who need to be affected; and broadening the scope of the fund to other sources of structural adjustment, including intra-EU trade, climate, and related policies.[29] In addition, the payouts per worker averaged just €4,219 over the period 2007–16, well short of the amount needed to redirect a career cut short,[30] while the time taken to approve schemes should surely improve on the minimum six months.[31]

What Should the New Commission Do?

In September 2018, the outgoing European Commission unveiled the “Africa-Europe Alliance for Sustainable Investment and Jobs,” an ambitious statement of intent for deepening economic relations between the continents. Tapping the full potential of integration and trade is a key pillar of the Alliance, and its proposed actions include increasing and diversifying trade between the EU and Africa, lending support to the AfCFTA via more AfT, and enhancing intra- and inter-regional connectivity. These are sound objectives, but their achievement will require that the EU make ambitious changes. The new Commission should:

-

Work towards ending tariffs on imports from Africa and reform rules of origin to permit increased cumulation. The EU should continue to liberalise its remaining tariffs on imports from Africa and improve the impact of these preferences by reforming rules of origin. Offering different market access terms to different African countries under the GSP, Everything But Arms, and various free trade agreements leads to distortions and undermines regional integration. It adds to the complexity of EU rules of origin due to the need to prevent trans-shipment of African exports through countries with more favourable terms. The new Commission should work towards providing duty-free access to EU markets for all African countries, irrespective of geography or income-level. These concessions should be offered unilaterally and could be a feature of the new AfCFTA, thereby encouraging adoption.

Because WTO rules require that eligibility for GSP schemes be based on objective developmental criteria, the EU cannot easily introduce unilateral tariff preferences that discriminate in favour of African producers. Instead, it could extend tariff-free access beyond LDCs to all low- and lower-middle-income countries, replacing its current multi-tiered GSP scheme with a simplified arrangement that would apply to 51 out of 54 African economies. Though LDCs would lose some of the competitive advantage that lower relative tariffs afford them in European markets, this loss could be mitigated using the EU’s existing graduation mechanism, whereby preferences are withdrawn from country exports that are “highly competitive,” as assessed by objective criteria. This would help ensure that no single large country dominates an entire sector-market. As a second-best option, the EU could follow the precedent set by the African Growth and Opportunity Act, the US preference scheme for sub-Saharan Africa only, and seek a WTO waiver.

The EU should also reform its rules of origin in line with the WTO Ministerial Declaration for LDCs. This would involve lowering minimum domestic content requirements from 30 to 25 percent and providing for extended cumulation. At a minimum, the EU should allow African country exporters to cumulate inputs from other countries in the region. It could further permit cumulation of products that can be imported into the EU duty-free, regardless of origin.

-

Improve the effectiveness and impact of EU Aid for Trade in Africa by piloting payment by results. Policy choices within African countries matter more for their export performance than EU tariffs and rules. AfT is the EU’s main lever for influencing these choices, but evidence of effectiveness is lacking. The EU can improve its offer by making increased use of results-based programmes which also ensure EU funds are only spent if successful. Drawing on earlier CGD work,[32] the case for employing payment by results in AfT programmes is:

Payment by results (paying for outcomes, not inputs) is most appropriate where local contextual knowledge matters, where the best combination of inputs is uncertain and local experimentation is needed, and where precise design features and implementation fidelity are most critical. All these criteria apply to AfT.

[In] a typical AfT programme… payments would typically be made for activities (for example, technical assistance for improving a certain process) that, according to a theory of change, should lead to the desired outcomes. But contracting for activities and inputs doesn’t allow for sufficient experimentation and change. A better approach is to contract for outcomes … and allow those with the required information the flexibility to determine the best way of achieving those outcomes.

In the context of the AfCFTA, the EU could condition AfT on measures of the cost of importing and exporting across African borders. These are a close proxy for the presence of non-tariff barriers, the removal of which are critical to the AfCFTA’s success.

-

Reduce agricultural subsidies to even the playing field with African producers. The new Commission should accelerate plans to eliminate harmful agricultural subsidies. While the pathway for the EU agriculture budget appears to be downward, the new Commission should ensure there is no backsliding, and should make the case for spending of greater benefit to EU citizens, and which does not undermine development in the EU’s trade partners. The pressing nature of climate change and poor value of this spending must be drivers to ensure the EU no longer has to explain why over a third of its spending is essentially wasted on agriculture.

-

Reform the European Globalisation Adjustment Fund. The European Globalisation Adjustment Fund remains unambitious in its €150 million budget, scope, and design. There is a significant opportunity to expand the workers that can benefit; to broaden the scope of the fund to other sources of structural adjustment (including intra-EU trade, climate, and related policies); and to accelerate and increase payouts from around €4,000 to an amount that genuinely funds a redirection in a career cut short. Together, this comprehensive approach to structural adjustment would demonstrate the EU’s ability to benefit from and adjust to major economic change, and help avoid the failures of the United States in response to China’s and Latin America’s rise.

[1] For example, see Subramanian, A. and Wei, S. (2003) “The WTO Promotes Trade, Strongly but Unevenly,” NBER Working Paper No. 10024, www.nber.org/papers/w10024.

[2] AUC/OECD. (2018) “Africa’s Development Dynamics 2018: Growth, Jobs and Inequalities,” Addis Ababa: AUC/Paris: OECD Publishing, pp. 42 and 46.

[3] The Economist (January 24, 2019). “Globalisation has Faltered,” www.economist.com/briefing/2019/01/24/globalisation-has-faltered.

[4] For example, Karingi and Mevel estimate that if African countries eliminated tariffs for intra-regional trade, the value of that trade would increase by 52 percent over 10 years, with the greatest expansion occurring for industrial exports. See Karingi, S. and Mevel, S. (2012) “Deepening Regional Integration in Africa: A Computable General Equilibrium Assessment of the Establishment of a Continent Free Trade Area followed by a Customs Union,” Paper for presentation at the 15th Global Trade Analysis Project Conference, Geneva, June 27–29.

[5] United Nations Economic Commission for Africa, African Union, and African Development Bank (2017) “Assessing Regional Integration in Africa VIII: Bringing the Continental Free Trade Area About,” Addis Ababa: ECA Printing Unit, p. 87.

[6] Ibid., p. 65.

[7] Ibid., p. 2.

[8] Woolfrey, S. and Apiko, P. (February 15, 2019). “The African Continental Free Trade Area: The Hard Work Starts Now.” https://ecdpm.org/talking-points/the-african-continental-free-trade-area-the-hard-work-starts-now.

[9] European Commission (2018, September 12). “Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council and the Council. A new Africa—Europe Alliance for Sustainable Investment and Jobs: Taking Our Partnership for Investment and Jobs to the Next Level.”

[10] Center for Global Development (2018) “The Commitment to Development Index,” www.cgdev.org/commitment-development-index-2018#CDI_TRA.

[11] See Thelle, M. (2015) “Assessment of Economic Benefits Generated by the EU Trade Regimes Towards Developing Countries,” https://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2015/july/tradoc_153595.pdf; Development Solutions Europe. (2018) “Mid-Term Evaluation of the EU’s Generalised Scheme of Preferences (GSP),” https://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2018/october/tradoc_157434.pdf.

[12] Hoekman, B. and Winters, A. (2016) “UK Trade with Developing Countries After Brexit,” Sussex: The UK Trade Policy Observatory. p. 17.

[13] Listen Notes (August 1, 2017) “Trade Talks: Dr. Stephen Hurt Talks Trade, Development, and Economic Partnership Agreements,” www.listennotes.com/podcasts/talking-trade-post/dr-stephen-hurt-talks-trade-OzvQMk5o_LZ.

[14] Jones, E. and Copeland, C. (2017) “Making UK Trade Work for Development Post-Brexit,” www.geg.ox.ac.uk/sites/geg.bsg.ox.ac.uk/files/Making%20UK%20trade%20work%20for%20development%20post-brexit.pdf.

[15] www.wto.org/english/thewto_e/minist_e/mc10_e/l917_e.htm.

[16] Hoekman, B. and Winters, A. (2016), p. 26.

[17] In 2017, the Two Main EU Agriculture Schemes—the European Agricultural Guarantee Fund and European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development—Spent €55.8 Billion Out of an EU Total Expenditure of €137 billion. See http://ec.europa.eu/budget/figures/interactive/index_en.cfm.

[18] OECD (2018) Producer and Consumer Support Estimates Database. Retrieved June 20, 2019, from www.oecd.org/southafrica/producerandconsumersupportestimatesdatabase.htm.

[19] Center for Global Development (2018) “The Commitment to Development Index (Trade Component),” /commitment-development-index-2018#CDI_TRA.

[20] Simulation results suggests even recent “greening” reforms deliver little environmental benefit. For example, see Gocht, A., Ciaian, P., Bielza, M., Terres, J. M., Roder, N., Himics, M. and Salputra, G. (2016). Economic and Environmental Impacts of CAP Greening: CAPRI Simulation Results. EUR 28037 EN, Joint Research Centre, European Commission. doi: 10.2788/452051.

[21] Basnett, Y., Engel, J., Kennan, J., Kingombe, C., Massa, I. and te Velde, D. M. (2012) “Increasing the Effectiveness of Aid for Trade: the Circumstances Under Which it Works Best,” Overseas Development Institute Working Paper 535, www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/odi-assets/publications-opinion-files/7793.pdf.

[22] UNECA et al. (2017), p. 113.

[23] OECD CRS database. Retrieved April 3, 2019.

[24] European Commission (November 13, 2017) “Achieving Prosperity Through Trade and Investment: Updating the 2007 Joint EU Strategy on Aid for Trade,” https://publications.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/2aea409b-c860-11e7-9b01-01aa75ed71a1/language-en/format-PDF/source-48763849.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Timmis, H. (2017) “Promoting Intra-Regional Trade in North Africa,” K4D Helpdesk Report, Institute of Development Studies, Brighton, UK, www.gov.uk/dfid-research-outputs/promoting-intra-regional-trade-in-north-africa.

[27] European Globalisation Adjustment Fund, https://ec.europa.eu/social/main.jsp?catId=326.

[28] https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/en/funding/available-budget.

[29] Claeys, G. and Sapir, A. (2018) “The European Globalisation Adjustment Fund: Easing the Pain from Trade,” http://bruegel.org/2018/03/the-european-globalisation-adjustment-fund-easing-the-pain-from-trade.

[30] Ibid.

[31] Puccio, L. (2017) “Policy Measures to Respond to Trade Adjustment Costs,” Brussels: European Parliamentary Research Service, www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2017/614597/EPRS_BRI(2017)614597_EN.pdf.

[32] Crawfurd, L., Mitchell, I., and Anderson, M. (2017) “Beyond Brexit: Four Steps to Make Britain a Global Leader on Trade for Development,” Center for Global Development Policy Paper 100, www.cgdev.org/publication/beyond-brexit-britain-global-leader-trade.

Rights & Permissions

You may use and disseminate CGD’s publications under these conditions.