Recommended

Blog Post

IMF and World Bank 2022 growth projections for emerging markets and developing economies (EMDEs), released in January this year, were not encouraging. They found that deteriorated macroeconomic fundamentals, partly resulting from policy responses to the pandemic, deep institutional deficiencies, and social and political unrest in several countries, had combined to severely weaken the engines of growth in many economies. Moreover, inflationary pressures were on the rise—in part due to external factors, most notably important supply chain disruptions and increases in the price of energy and, in some cases, significant pass-through effects from currency depreciation. Some analysts expressed concern that many countries could be entering a period of stagflation, with slow growth and high inflation.

Enter Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. In a recent press conference, the IMF managing director alerted that the institution will likely revise downwards global growth projections during its forthcoming Spring Meetings. And the OECD has already estimated that global economic growth could be more than 1 percent lower this year than predicted before the eruption of the conflicts. For many countries, the outlook has become even bleaker.

How severely will EMDEs be impacted by the war in Ukraine?

The answer depends on the duration, spread, and intensity of the war—all highly uncertain at this time. But it also hinges on the economic policies of advanced economies, particularly monetary policy, which affects global liquidity. It is well documented that the macroeconomic effects of the Ukraine crisis flow through intertwined commercial and financial channels. In the commercial channel, the large increases in commodity prices adversely affects net importers of these products the most, with net exporters benefiting from a positive terms of trade shock. In the financial channel investors’ risk perception associated with the uncertain evolution of the conflict have increased. Capital flows to EMDEs are strongly influenced by investors’ risk perceptions, but also by the return from EMDEs’ assets. If global liquidity remains abundant and the yield offered by emerging markets’ securities relative to those offered in advanced economies remains high, the jump in risk may be partly offset by high yields, containing the potential capital outflows from EMDEs. Here is where the Fed and other central banks in advanced economies play a key role.

The stylized facts: commodity prices and global liquidity

Figure 1 shows markets’ expectations on commodity prices reflected in the prices of futures. The dashed line shows expectations at the beginning of the year (pre-conflict) and the solid line shows the corresponding expectations in the second half of March (during the conflict). Although prices are expected to decline over the medium term, futures for most commodities are now much higher than they were pre-conflict, signaling a significant and persistent adverse shock to the terms of trade of net commodity importers.

Figure 1. Commodity prices futures: pre- and during conflict expectations (Index: 100 = spot price as of March 28)

Source: Bloomberg.

Note: Pre-conflict data is for the earliest data points in January 2022 (January 3) and conflict data is the latest available (March 28).

What about strains in financial markets? There are well-known indicators to gauge the current situation, including the US Treasury OFR Financial Stress Index, which measures tension in global financial markets, and the EMBI global spread, an indicator of risk of emerging markets’ government bonds. Sharp and sustained increases in these indicators are associated with episodes of deep financial and economic troubles in emerging markets; a significant increase in investors’ risk perception triggers a move towards safe assets (such as US Treasury bonds) and a reduction in available global liquidity to meet emerging markets’ financing needs.

Figure 2 shows the recent evolution of the Financial Stress Index and the EMBI global spreads.[1] Although both indicators abruptly increased at the beginning of the war, they have, at least partially, corrected the initial jump. Furthermore, at their peaks, the increases in both indicators were well below those observed during periods where global liquidity shortages were a serious problem for emerging markets, such as during the Global Financial Crisis and at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Figure 2. OFR Financial Stress Index (FSI) and EMBI global spreads 2007-2022

Source: Dominican Republic Central Bank and US Treasury Office of Financial Research (OFR).

Despite the war, global liquidity that can be directed towards EMDEs’ assets remains ample. Although the Fed has made clear its determination to fight inflation through a series of interest rate hikes, real rates, namely, nominal rates deflated by inflation, remain quite negative across the entire yield curve. Moreover, real rates are also negative in Europe, and it is expected that the European Central Bank will not start hiking the policy rate until the last quarter of 2022 at the earliest. Negative real rates create strong incentives for investors to fund riskier assets. Thus, EMDE have not yet faced a drastic squeeze in liquidity. Risk aversion towards EMDEs may have increased but not sharply.

Assessing EMDEs’ vulnerability to the war

As long as global liquidity remains abundant it is hard to expect generalized distress in EMDEs from the war. The moderate increase in risk aversion likely signals additional investors’ differentiation between countries when allocating resources, rather than broad capital outflows. But this could change if, motivated by persistent inflationary pressures, the Fed and other central banks in advanced economies increase interest rates more abruptly and quickly. As of now, however, we expect that the most affected countries will be those where the war is sharply increasing their external financing needs and where large stocks of outstanding debt pressure their external financing costs. If the conflict continues over a prolonged period, those countries may face severe difficulties in refinancing external obligations, with significant adverse consequences for economic growth.

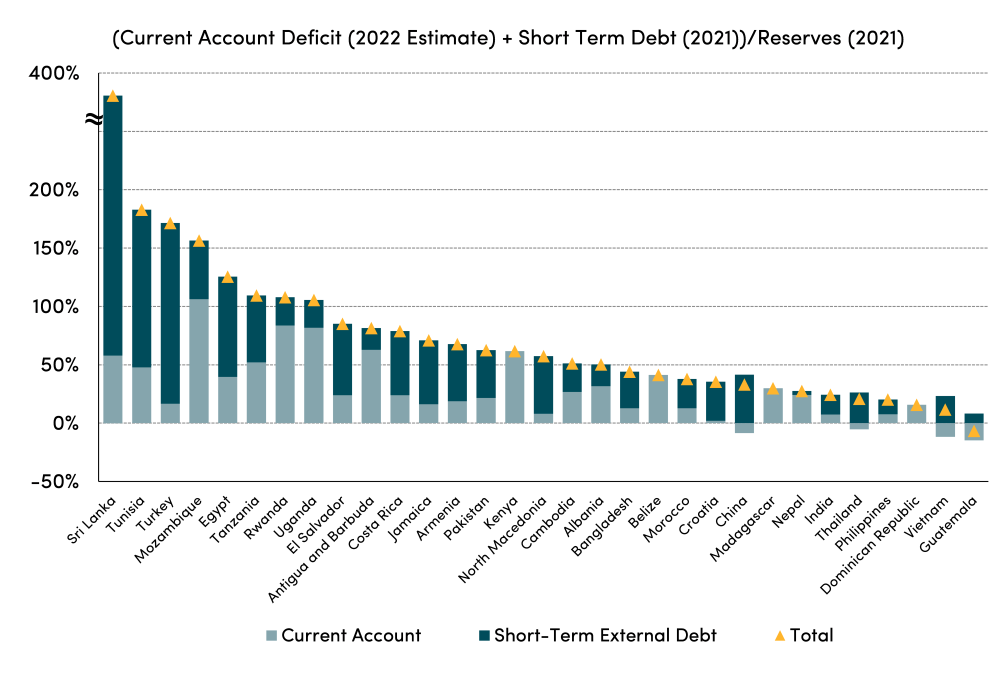

Who would be most affected? A common indicator of external financing needs is the ratio of current account deficits plus short-term debt to international reserves. The higher this ratio, the lower the capacity of a country to show that it has sufficient resources in hard currency (currencies that are internationally tradable and highly liquid, such as the US dollar) to meet its external obligations. In times of increased global uncertainty, large accumulations of international reserves become especially handy.

Thus, countries whose financing needs would be most affected are the net importers of commodities who have high ratios of short-term debt to international reserves. To identify net commodity importers, we subtract the total value of commodity exports from the total value of commodity imports for each country, using United Nations data.[2]

Consider first how the external financing needs of net commodity importers looked before the onset of the war. A good approximation can be obtained by first adding the October 2021 IMF’s World Economic Outlook projections for current account balances for 2022 to the existing stock of short-term debt by end-2021. This value can then be divided by the stock of international reserves at the end of 2021.

Figure 3 shows these ratios for a selected group of net commodity importers. Most Eastern European countries are not included in the graph because their proximity to Russia makes them subject to many more risks than a deterioration in the terms of trade, including the potential for further involvement in the conflict, that could jeopardize their financing needs in unpredictable ways.

Figure 3. External financing needs in selected net commodity importers

Source: IMF (October 2021 World Economic Outlook, International Financial Statistics and countries’ Article IV) and World Bank (Quarterly External Debt Statistics and International Debt Statistics).

For the set of countries in Figure 3, a persistent increase in commodity prices represents a substantial adverse terms of trade shock and would, most likely, increase their financing needs for 2022.

By the end of 2021 there was a large differentiation between countries. Consider, for example, Guatemala, Vietnam, Dominican Republic, the Philippines, and Thailand on one extreme, and Sri Lanka, Tunisia, Turkey, Mozambique and Egypt on the other. Oil, gas, and minerals are among the most important imports in all these countries (with Egypt and Mozambique, Tunisia and Sri Lanka being also large importers of wheat). However, due to their substantial stock of international reserves and relatively small ratios of short-term debt, Thailand, the Philippines, and the Dominican Republic could likely withstand a large deterioration in their current account balance in 2022 in the face of persistent high prices of the commodities they import. And Guatemala, like Vietnam, entered the war period with current account surpluses. While the war will affect growth prospects, severe financial distress is unlikely given the strong initial conditions of these countries.

In contrast, Sri Lanka, Tunisia, Turkey, Mozambique, and Egypt were already quite vulnerable to external shocks before the eruption of the conflict—their stocks of reserves were not enough to cover for their financing needs. By aggravating their already compromised macrofinancial stability, sustained high commodity prices might push some of these countries over the edge. Before the current shock, Turkey was dealing with the highest inflation rates in the last 20 years, while making unorthodox policy decisions and experiencing increasing social turmoil. Egypt, further affected by the decrease in tourism revenue, is asking for IMF support, and Sri Lanka, Tunisia and Mozambique are already in talks for IMF programs.

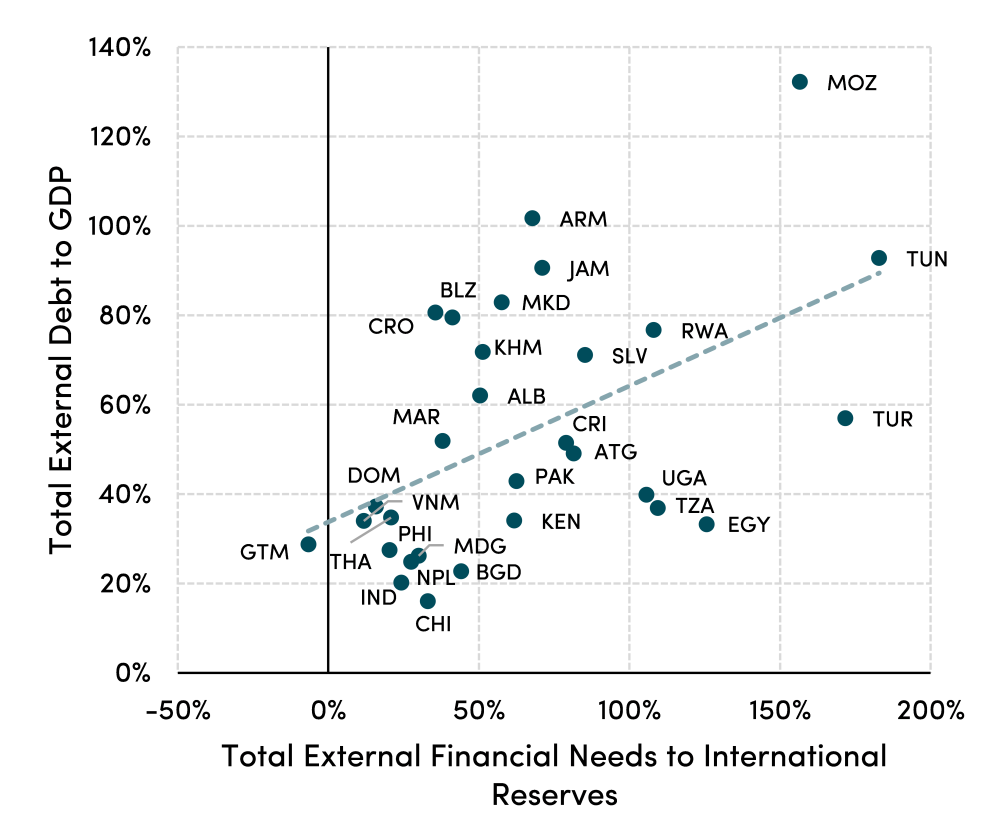

The assessment above can be complemented with data on countries’ overall external liabilities. Large stocks of debt (short- and long-term) imply large payments to service it (amortization plus interest). Figure 4 shows the relationship between total external debt to GDP (a stock aggregate) and external financial needs (a flow aggregate and as defined in Figure 3) for the same set of net commodity importer countries.

Figure 4. External debt to GDP in selected net commodity importers

Source: World Bank and IMF

Note: We exclude Sri Lanka for readability (its external financing needs exceed 350 percent of international reserves).

Not surprisingly, there is a close positive relationship between countries with large financing needs for 2022 and those with large ratios of external debt.[3]

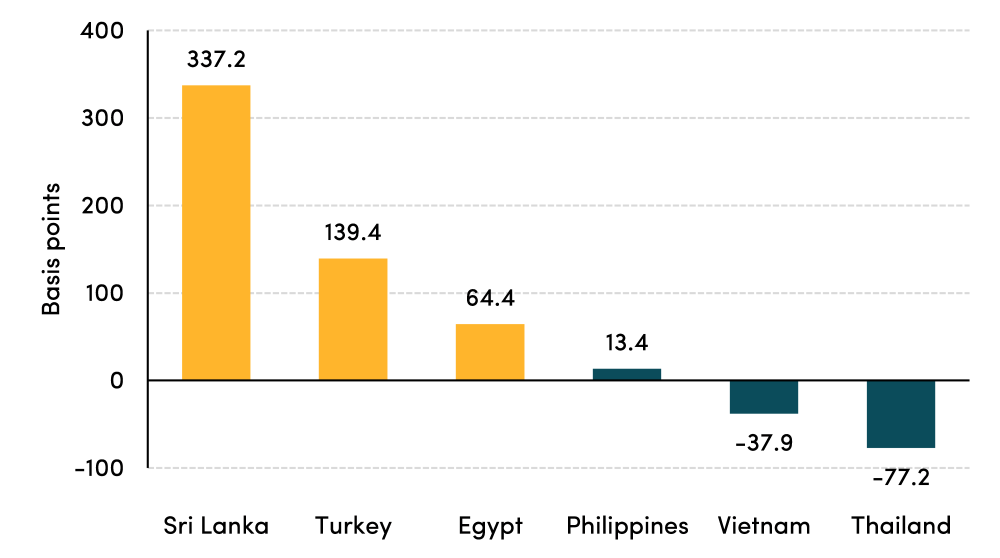

This important country differentiation is reflected in investors’ risk perceptions as reflected in the spreads between a country’s 10-year government bonds yield and the 10-year US Treasury bond. As shown in Figure 5, from the beginning of the year to March 28, and despite hikes in US interest rates, the spreads increased substantially in Sri Lanka, Turkey, and Egypt, three of the most vulnerable countries to the effects of the Ukrainian war. In contrast, during the same period, the spreads have either remained practically constant or even decreased in the Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam, three of the strongest net commodity importers in our sample.

Figure 5. Change in 10-year government bonds’ spreads (between January 3, 2022 and March 28, 2022)

Source: World Government Bonds.

Summing up

The Ukrainian war will be a hard blow to those countries that are net commodity importers and face large external financing needs, as the conflict is exacerbating their preexisting vulnerabilities. Whether the impact of the conflict spreads further throughout the EMDEs group depends on two factors. The first is, of course, the evolution of the war and the impact of sanctions on the global economy. The second lies with the reaction of central banks in advanced economies, especially the Fed, to the surge in inflation. If interest rate hikes are larger and faster than expected, global liquidity may shrink sharply, investors’ risk aversion may escalate, and capital flows to EMDEs may decrease or even reverse. If any of these external conditions worsen, they may drastically increase the severity of the impact on EMDEs and their prospects for economic recovery after COVID-19.

[1] EMBI is the JP Morgan Emerging Markets Bond Index. The EMBI Global spread is the difference between an (asset weighted) indicator of emerging markets’ yields in secondary markets and the yield on 10-year US Treasury bonds. The shaded areas correspond with the Global Financial Crisis and the beginning of the pandemic. Values of the OFR FSI above zero indicate that financial stress is above normal historical levels.

[2] Commodities are defined following the IMF classification from the October 2021 World Economic Outlook (p. 87) and include Standard International Trade Classification codes 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 68 and 97.

[3] Zooming in on the debt issue, looming (and present) debt distress has been threatening some low-income countries, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, for a while. Among economies in our sample, and according to a World Bank classification that precedes the Ukrainian war, Mozambique was in “debt distress,” which means that it was “already experiencing difficulties in servicing its debt.” Others, like Tanzania, Rwanda, and Uganda were considered to face “moderate” risk; however, the recent shock to commodity importers will likely increase pressures on these countries. Consistent with the World Bank classification, Bangladesh was in “low” risk of facing debt distress, has under 50 percent of external debt as percentage of GDP and is in the lower percentiles of our external financial needs’ distribution.

Rights & Permissions

You may use and disseminate CGD’s publications under these conditions.