Recommended

China has emerged over the past decade as the world’s second-largest economy and its policies and development approach have a major bearing on global development. That’s why, alongside other G20 countries that hadn’t previously been included like Brazil and Turkey, we have assessed China in this year’s Commitment to Development Index (CDI).

We find that, taking into account its size, China’s policy commitment to development ranks 35th of the 40 countries in the index. In the seven components assessed in the CDI, China scores well on technology; below average on environment, migration, and trade; and poorly on investment and security. In development finance, where you might imagine China would score strongly, our measures ranked it last.

Some of those results may seem counterintuitive: Most people know that China provides major levels of finance to Africa, and that it’s a big producer of greenhouse gases. However, after we take account of country size to enable comparisons between countries, our index ranks China last on development finance but well above the US and in the top ten on limiting greenhouse gas emissions.

Why these unexpected results? How much do China’s other policies do for international development?

Isn’t development finance China’s strength?

China is a major lender to developing countries, with a total stock of lending estimated to exceed $400 billion and annual lending that could be as high as $40 billion. This is a similar level of lending to the World Bank, yet China comes solidly last on our development finance component, which assesses the financial assistance provided to poorer countries. What explains the apparent discrepancy between its low score and large financing flows?

The first reason is that we assess both quantity and quality, and on the latter, China is lacking. The details of China’s lending are highly opaque—trying to assess the extent of its activities has spawned an entire field of research—which limits scrutiny and challenge. China is also penalised for requiring that its finance projects must be performed by Chinese firms. Its poverty and fragility focus are above average, but few countries responded to the Global Partnership for Effective Development Cooperation survey to confirm China’s commitment to providing finance in line with their national priorities, even if China prides itself on respecting “the right of the recipient country to independently choose the path and mode of development.”

But even on quantity, China ranks 38th, as the large reported flows are only partly concessional, and small compared to China’s vast economy. Although hampered by a lack of official information, the best estimates of China’s loans suggest that the subsidy element (or “grant-equivalent”) is relatively small. So, from a face value potentially as high as $40 billion a year, we estimate the grant-equivalent value, along with direct grants, to be “just” $5 billion. That’s just 0.04 percent of China’s GNI, compared to an average over the 40 CDI countries of 0.3 percent of GNI.

This finding, although immediately counterintuitive, actually fits with wider work on this subject. China’s official lending is very large and near-commercial, which make it affordable to provide but also a concern in terms of affordability and indebtedness.

Is it fair to compare China against OECD and other standards?

We have strived to use measures and data that are applicable to each of the 40 countries in the CDI (indeed, we altered many of our measures to achieve this). Still, China and some other G20 countries do not subscribe to several of the standards we assess. This is most obvious in our investment component: on commitments against standards from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) on anti-corruption; the United Nations (UN) on business and human rights; and measures of financial secrecy compiled by a UK think tank. It’s not only new additions: Switzerland and the US have not signed up to the UN target on aid—but we still assess them against it. The bottom line is if China (or indeed any of the countries that do not meet them) did meet these standards, the world would get better more quickly, so we think it’s right to include them.

For China, we could not identify data for three of our (52) indicators. China was given the average on these measures as we felt it could not be expected to report on some indicators (like those of the OECD) so did not unduly hold back China’s score. Still, for other countries added, notably Saudi Arabia and UAE, there were penalties for missing data for several indicators that they should be reporting. Still, if more information was available—for example on China’s loan portfolio—it may show that its development effort was higher than we were able to demonstrate.

Finally, to recognise that development responsibility rises with income, we produce income-adjusted scores. These look at what CDI score we’d expect based on income level, and then look at how far above or below that score countries come. China’s position is essentially unchanged—it rises one place to 34th, suggesting that it is below what might be expected of it based on its relatively low income level.

What to make of China’s environmental performance

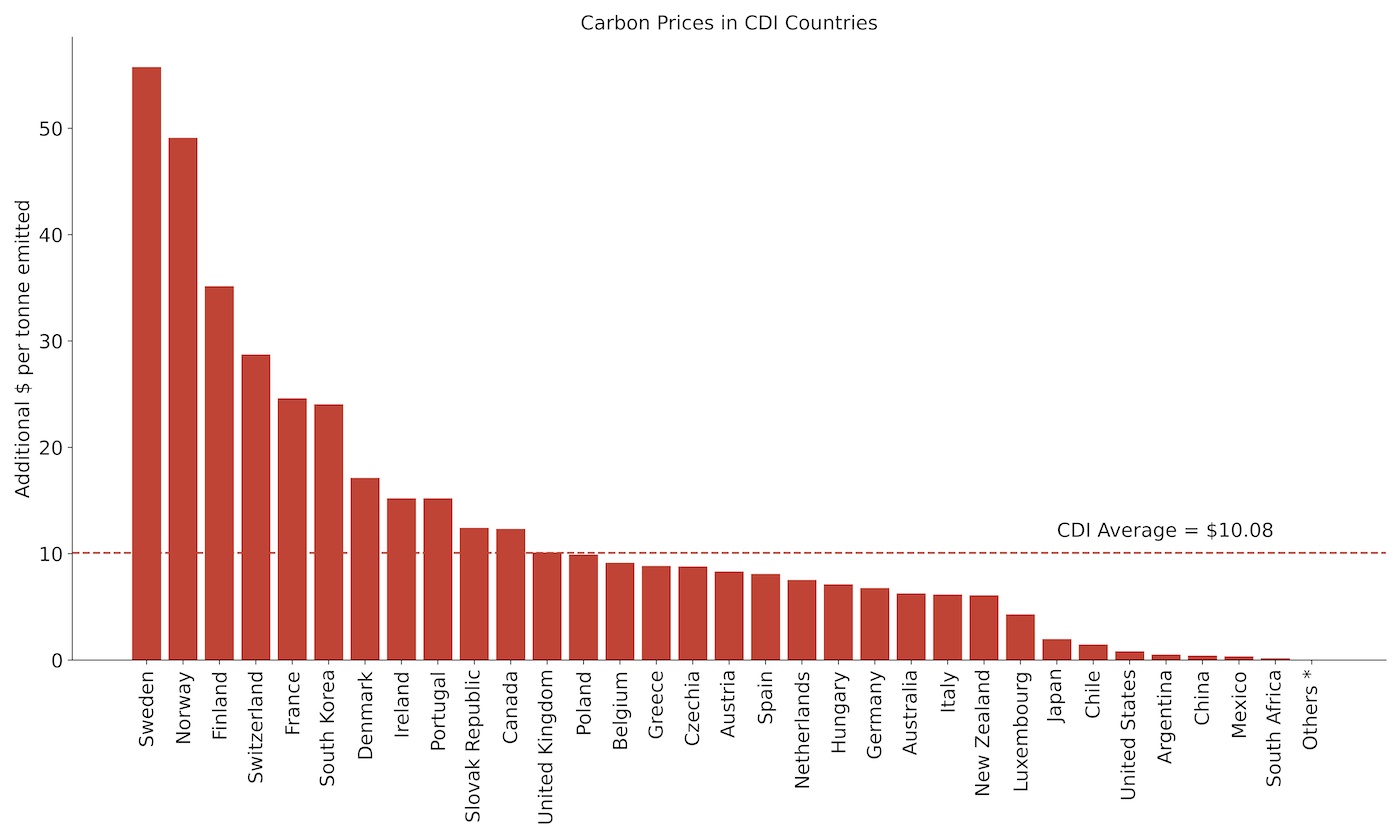

China ranks 24th on the environment component—below average, but also well above the US, which ranks 35th.

The main driver of this is climate: China’s direct per-head emissions (9 tonnes) are under half of those of the US (20 tonnes). And the gap grows when indirect emissions embedded in imports are taken into account (typically half as much again). Across both, China is currently among the top 10 in low emissions per head. This partly reflects China’s low economic output per head, though the income-adjusted results show its emissions are in line with expected levels, and still performs better than the US.

China has plenty of room for improvement on environmental issues—fossil fuel production and subsidy, subsidies to fishing, and environmental conventions—but the CDI demonstrates every country is a long way from net zero emissions.

Technology a strength

On technology, China rank 14th. Although second only to the US in absolute terms, China’s spend on public research and development (R&D) is unremarkable when measured against the size of its economy. It does offer some of the highest support for commercial R&D, though. China’s tertiary student body is also above average in reflecting the international and developing world. Still, where China scores top—perhaps surprisingly considering the value the government places on technology—is that it places few restrictions beyond World Trade Organization norms on intellectual property rights in its bilateral trade deals. And here, other countries could learn from China’s approach.

The CDI’s rankings are an opportunity for policy improvement

We’ve included the G20 countries in the CDI to consider their policies against the framework we have developed over fifteen years in supporting development, given the increasingly important role China and other new donors play. We think that this exercise has identified areas where all countries could improve their policies, very often to the benefit of their own people, and support other countries’ development, especially the poorest.

We hope our results start a dialogue around that—and look forward to discussing our results further.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.