Recommended

Blog Post

This blog first appeared on Barron's as an op-ed.

Every country faces the same fundamental challenge in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic. Their economies and societies cannot fully return to “normal” until we have a safe and effective vaccine. And achieving that goal quickly is not easy. We see four big problems.

First, the science is hard. Governments and foundations are investing resources into scientific research and discovery for over 100 early-stage vaccine candidates; a few promising prospects have progressed to initial human trials. Many promising vaccine candidates fail in later stage trials or offer only middling efficacy. This winter, for example, South African researchers aborted a $100 million Stage III HIV vaccine trial because new infections in the vaccinated group exceeded infections in the placebo arm. A malaria vaccine supported by about $800 million in private-sector and philanthropic funds eventually received regulatory approval—but offers only 29 percent protection against severe malaria in children, and only after four doses. Investment in vaccine R&D, critically important, is still expensive, high-risk, and uncertain to produce a highly effective product.

Second, the market is fragmented and uncertain. Without effective therapeutics, there are clear market signals now that a vaccine would be purchased in high-income countries—but even in wealthy countries, a treatment breakthrough or gradual development of herd immunity may dramatically change the market landscape over a medium-term time horizon. The market in low- and middle-income countries remains a big question mark. Uncertainty may deter some companies, even with promising candidates, from putting up funds for late-stage clinical trials.

Third, manufacturing scale-up could be slow, expensive, and vulnerable to export controls. Even if we see scientific success and clear market signals, manufacturing scale-up takes time—and billions of dollars in resources. Meeting global demand for a Covid-19 vaccine would at present mean utilization of most or all of the world’s current capacity to produce vaccines and package them, known as finish/fill. Availability of raw materials for production of a specific vaccine may generate additional bottlenecks, while extensive fill/finish capacity will be needed for any candidate. Countries like China and India control major stakes in supply chains for active pharmaceutical ingredients, glass vials, and adjuvants; without their engagement and cooperation, export controls for key materials could further slow manufacturing scale-up.

Finally, competition for scarce supply would lead to long delays in access for large, economically important middle-income countries. Assuming their demand holds, countries like the U.S. and France could afford to compete and acquire sufficient quantities of vaccine; if their taxpayers are willing to contribute, traditional donor-funding approaches can help low-income countries buy together via Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance. But populous, economically important middle-income countries like Brazil, India, and South Africa—which could help chip in for vaccine production but are also home to most of the world’s poor—might miss out on a vaccine for many years.

To address these issues we must: assure that the most efficacious and affordable vaccines make it through the pipeline; increase the predictability of market returns so that companies invest in development and manufacturing; mobilize as many suppliers and countries as possible to prepare to scale manufacturing to global demand; and engage large middle-income countries to help pay for vaccine development and deployment. In a new paper with PATH and the UK Office of Health Economics, we expand on these problems and propose solutions.

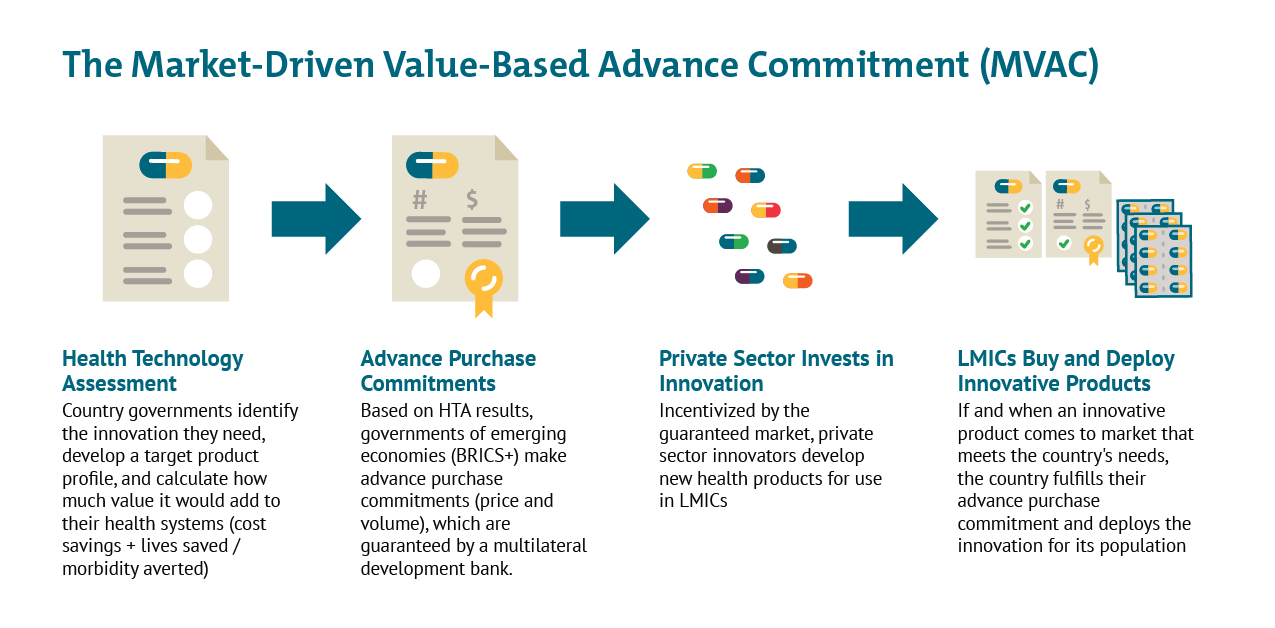

What is clear from our work is that U.S. leadership will be essential to tackle these challenges. The largest economy and market in the world, the U.S. has been instrumental in supporting global health initiatives for decades and has crucial scientific assets like the federal research agency Barda. But the U.S. will be most effective if it leads a global partnership, sharing the burden of financing and manufacturing an eventual vaccine with countries across the world and hastening a global economic recovery clearly in its interests. And using a modified version of the advance market commitment, a tool we developed to help finance other treatments, would allow the U.S. to lead the world while making sure all countries pay their fair share.

Here’s how the AMC would work. The U.S. should convene a global pledging conference where all country governments agree to a minimum and “ideal” target product profile for a coronavirus vaccine. Each country would make a binding commitment to buy enough doses to cover their entire populations in need at prices that reflect local value and affordability but would only pay if and when such a vaccine becomes available. Financial intermediaries, including government bonds, social impact bonds, national bank reserves, and multilateral development banks, could guarantee national purchase commitments; in this way commitments would be binding, but would not require up-front allocation of scarce public resources.

Countries would pay a higher price for more effective vaccines, and for vaccines that are made available more quickly, reflecting the high value of both efficacy and speed. Less-wealthy middle-income countries would pay lower prices than richer countries, reflecting their lower ability to pay but assuring that they contribute a fair share. The poorest nations would pay nothing at all; Gavi would buy the vaccine on their behalf at marginal cost, possibly through a medicines patent pool, and can support national roll-out. Countries would pay separately and up front to reserve manufacturing capacity; a successful vaccine developer would then pay to use that reserved capacity.

Given the extraordinary toll of COVID-19, the AMC should be at least in the tens of billions of dollars to create a large and robust market incentive for private-sector investment and maximize the probability of success. But since all but the poorest countries would be chipping in something, the total cost would be widely distributed. Multiple successful market entrants could share the pool, with faster entrants and more effective vaccines earning a larger slice of the pie based on their relative value.

This approach offers our best path forward to speed an effective vaccine, minimize waste, and make sure everyone chips in a fair share in this global endeavor of a lifetime.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.

Image credit for social media/web: Aisha Faquir/World Bank