Recommended

CGD NOTES

Who gets to be an “expert,” and who gets compensated for it?

At their best, experts sitting in think tanks generate rigorous research and analysis inform policies and address the world’s most pressing challenges. But who gets to be counted among these experts? Are think tanks hiring, promoting, and compensating equitably and inclusively? And who is being left out of this group of experts, and, critically, what good ideas might we be missing as a result?

Though statistics on occupational sex segregation and gender pay gaps across the United States are fairly well-documented, little is known about these issues at US-based think tanks specifically. In a new analysis, our colleagues sought to (partially) fill this gap by scraping publicly available data from IRS 990 tax forms on the highest earners and senior leaders present within an organization. They assigned genders to employees, trustees, and directors using a dataset built from the Social Security Administration’s application records in order to determine the breakdown of senior leaders and the highest earners among 71 US-based think tanks. Though evidence across sectors points to even lower representation for women of color among senior leaders and high earners, the data available here did not allow for a better understanding of intersectional gaps, like those based on race or ethnicity, at think tanks.

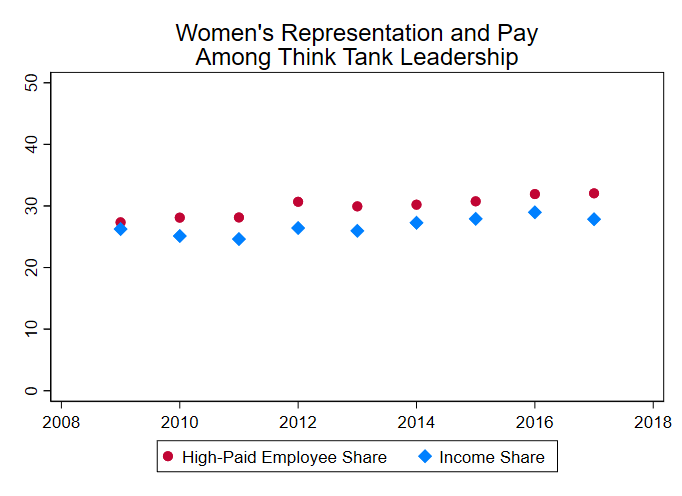

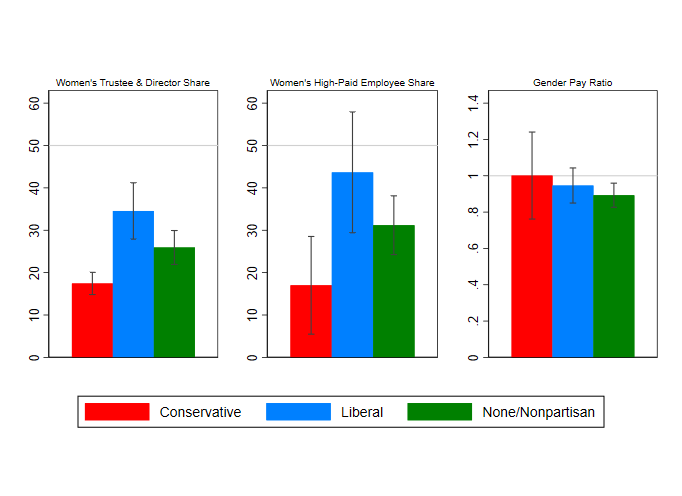

The analysis reveals large gaps in employment and some gaps in pay at the top end of think tanks. Women make up just 23 percent of trustees and directors, and 30 percent of highly compensated employees (“high-paid employee share” in the graph below). Both these rates hardly improved from 2011 to 2016. There is a wage gap between women and men working at the highest levels: highly compensated women are paid 92 percent of what highly compensated men are paid. This gap is modest in size in light of the fact that in the workforce at large (and we believe in think tanks, too), women make up a higher proportion of lower-paid employees than higher-paid employees.

Overall, out of every $100 paid to highly compensated think tank employees, less than $29 is paid to women (“income share” in the graph below). Conservative-leaning think tanks perform notably worse than the average on the share of high-paid employees who are women, as do think tanks that work on global development. Longer-established think tanks also see worse gender pay ratios.

Why do these gender gaps in leadership and compensation matter?

The first reason extends far beyond think tanks: any workforce gender gaps in leadership or pay (as well as a lack of equitable representation according to other demographic characteristics such as race, ethnicity, or sexual orientation) perpetuate unjustified inequalities in professional advancement and financial security.

The second reason is think tank-specific, given that these organizations by their nature are meant to influence policy. When think tanks’ expertise primarily reflects the viewpoints of a subsection of the population, the ideas and proposals generated risk being divorced from reality—at best, not fully reflective of the perspectives of those who will be affected by them, and at worst untenable, irrelevant, or even potentially harmful. Continuing to equate expertise with the views of mostly men reinforces discriminatory gender norms and holds back progress.

We know gaps in senior leadership and compensation stem in part from broader gender inequality in the workforce, and they are not exclusive to senior management and high earners. Instead, they manifest at that level because of gaps in advancement, success in negotiating for increased pay (when they do try to negotiate, women may not fare as well), and time out of the workforce due to disproportionate care responsibilities. These factors need to be addressed in order to eliminate gender gaps in senior leadership and pay.

Drawing attention to persistent gender gaps is only a first step towards progress; what it should allow is for organizations to self-reflect and then act to address inequalities. In our own workplace, CGD has mostly closed the wage gap, but only 43 percent of our highest paid employees were women from 2015-17, and our board of directors is about three-quarters men. Like many of our peers, we have much more work to do to truly “walk the talk” on promoting gender equality, diversity, and inclusion in leadership.

Recognizing this room for improvement, CGD has prioritized the recruitment of women as board members—and recently CGD has been fortunate to welcome women leaders Afsaneh Beschloss, Shubhi Rao, and Mary-Ann Etiebet to the board. CGD will also continue to prioritize institutional policies that promote unbiased hiring and promotion practices. To promote a more diverse and inclusive institutional culture more broadly, CGD has recently adopted a gender equality policy; aims to avoid all-male panels at events; and equips staff with diversity, equity, and inclusion training, a peer advisor network, and an external ombudsman for cases of discrimination and harassment.

There is no monopoly on good ideas and think tanks will need to include a more diverse array of perspectives to get to the best ones. We need to act to narrow the gender gaps reflected in available data, and push for better, more granular information on racial, ethnic, and other gaps. From there we can make real inroads for greater equality in the workplace and in the universe of ideas seeking to make the world a better place.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.

Image credit for social media/web: Hyejin Kang/Adobe Stock