The United States has an interest in a prosperous, secure Mexico—the second largest customer for American exporters. Is that interest adequately served by US policy?

The mainspring of that policy for 21 years has been the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), championed in the US by both George H. W. Bush and Bill Clinton. Pick your US interest group, and they’ll tell you that NAFTA either created or destroyed hundreds of thousands of American jobs (both are exaggerated).

But what’s going on beyond the fence? South of the border, NAFTA’s framers claimed, the agreement would mean better jobs and less poverty, lifting up Mexican opportunities toward US levels. And that was supposed to reduce migration pressure.

A new study by economists Davide Gandolfi, Timothy Halliday, and Raymond Robertson tests this idea in one of the clearest ways it could be tested. They study observably identical workers on either side of the border, who started out separated by a large gap in real wages (‘observably identical’ means the same basic tangible skills like education and years-of-experience. ‘Real’ wages means wages adjusted for price differences between the countries.) And test whether that gap has shrunk since NAFTA was signed.

And the result is…. no. It did not shrink, even a little. The gap has grown.

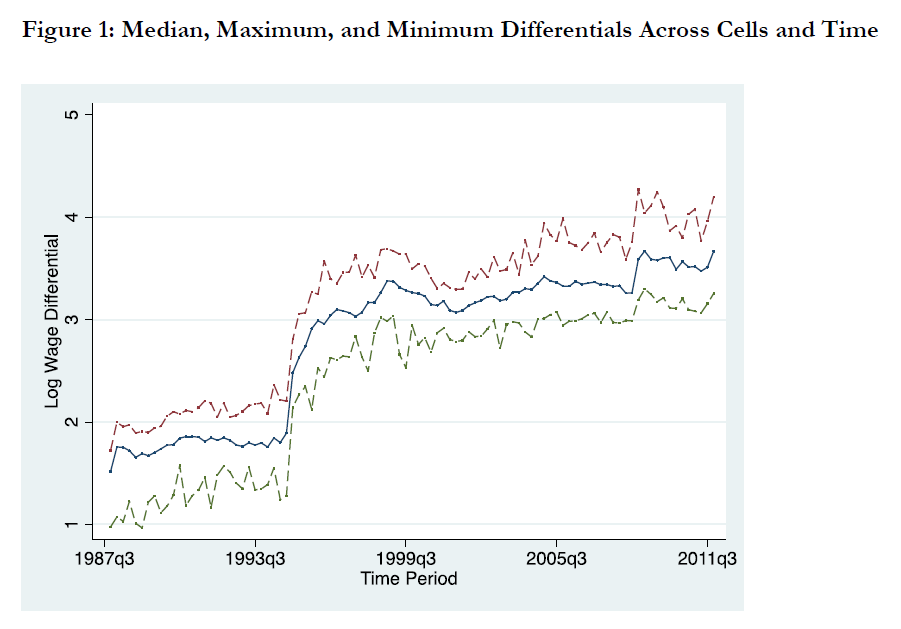

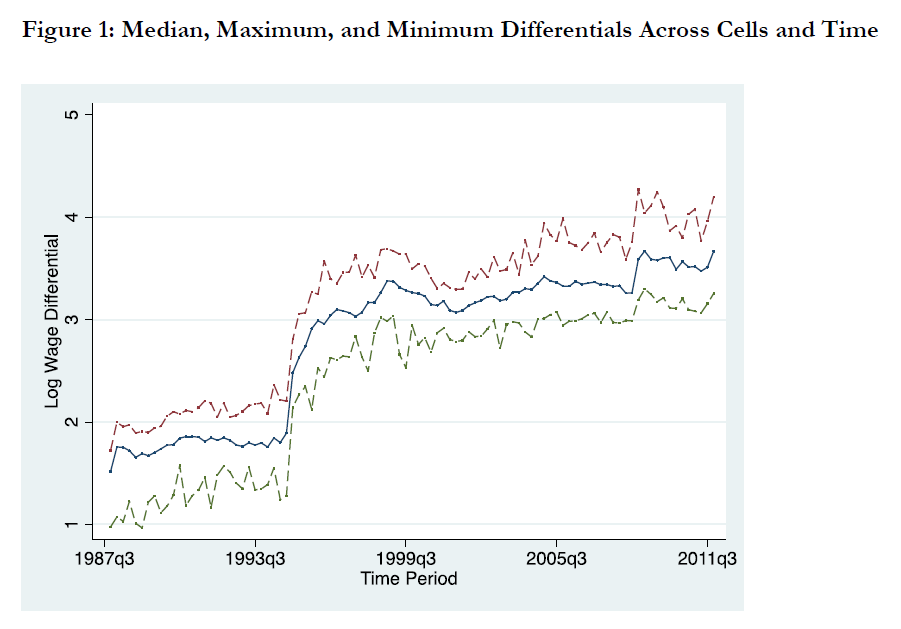

Below is the study’s estimate of the US-Mexico real wage gap over time, with NAFTA entering into force about a third of the way across the graph, in 1994. The authors measure gaps in 45 different education-experience “cells” (for example, one cell comprises people 19–23 years old with 6–8 years of education). Within each of those cells, workers have the same basic tangible traits. The blue line is the median gap between the countries across those 45 cells; the green line is the minimum, the red line the maximum.

Earlier, economist Gordon Hanson likewise found little sign of wage convergence in the first decade of NAFTA. Now, two decades in, that has not changed.

Why not? No one is sure, because so much else has happened over the same period—like the Tequila Crisis, two US recessions, and the drug cartel war. And things could still change as the years wear on. But these studies contain three clues to dig further.

- First, there was convergence within the education-experience cells that saw the greatest flow of labor from one country to another—despite tight legal restrictions on migration. NAFTA exemplifies what Lant Pritchett calls “everything-but-labor globalization”: it hoped wage convergence to arise from liberalizing trade and investment, but not migration. That hasn’t been sufficient. But migration can be sufficient to cause some measure of convergence. Labor markets can do some of what goods markets and capital markets cannot.

- Second, the study shows that even unrealistically high levels of migration would be far from sufficient to achieve full convergence in wages. No matter how freely people can trade, invest, or even migrate across a border, there may be limits on how much that alone can produce convergence in living standards between the countries. Something fundamental and immobile sticks a wedge between wages at the border. Daron Acemoglu and Jim Robinson illustrate this with the huge differences in living standards in different parts of Nogales, essentially a single town split in two by the US-Mexico border. The immobile thing sustaining the wage gap at the border, they argue, is principally the different economic and political institutions found on either side.

- Third, studies like this one don’t capture all the ways that wages can converge. Such studies are comparing people in education-experience cells on either side of the border, which is useful. But they’re not designed to capture convergence between living standards that arises when there are fewer people in low-wage cells. Take the cell of people age 19–23 with 6–8 years of education in Mexico. That cell can shrink in size in three ways: Demographic change can mean there are fewer 19–23 year-olds, and that is happening as fertility rates continue falling in Mexico. Education expansion can mean there are fewer people who leave school with 8 years or less, and that is happening in Mexico too. Finally, people in that cell can leave Mexico, and most of the wage gap with their American counterparts quickly disappears. The average wage of any given Mexican can rise even if wages within cells aren’t changing, as long as people are leaving low-wage cells in Mexico for higher-wage cells inside or outside Mexico.

The emerging lesson is that everything-but-labor globalization has been completely insufficient to foster US-Mexico wage convergence for observably identical workers. And everything-including-labor globalization would likely produce some convergence where a trade-and-investment-only deal failed, but far from full convergence. Full convergence requires institutional change, one of the most exciting and important areas of recent economic research. If you want an entry point, look to Acemoglu and Robinson, or to Avner Greif, or to Douglas North.

A EE.UU le interesa que México-el segundo mayor comprador de las exportaciones de EE.UU-sea un país más próspero y seguro. ¿Este interés se encuentra adecuadamente abordado por las políticas americanas?

El distintivo de esta política ha sido, por 21 años, el Tratado de Libre Comercio de América del Norte (NAFTA, por sus siglas en inglés), instaurado en EE.UU por George H. W. Bush y Bill Clinton. Elige tu afiliación política de interés en EE.UU y en esta te dirá que NAFTA ha creado o destruido cientos de miles de puestos de puestos de trabajo en EE.UU (ambos grupos exageran).

Pero, ¿qué está sucediendo Más Allá del Muro? Al sur de la frontera, los diseñadores de NAFTA argumentaron que este acuerdo generaría mejores empleos y menor pobreza, aumentando las oportunidades en México para converger hacia los niveles de EE.UU. Esto supuestamente reduciría la presión migratoria.

Un nuevo estudio de los economistas Davide Gandolfi, Timothy Halliday y Raymond Robertson pone a prueba esta idea de manera clara. Ellos estudian trabajadores equivalentes en ambos lados de la frontera, los cuales se encuentran diferenciados por una brecha amplia en salarios reales (‘equivalentes’ significa que los trabajadores poseen las mismas habilidades tangibles básicas como educación y años de experiencia. Salarios ‘reales’ son los salarios ajustados por la diferencia de precios entre ambos países) y prueban si esta brecha se ha reducido desde que NAFTA inició.

Y el resultado es… no. La brecha no se ha reducido, ni un poco. La brecha ha aumentado.

Debajo se encuentra el estimado del estudio sobre la brecha salarial real entre EE.UU y México en el tiempo, resaltando la introducción de NAFTA en 1994. Los autores miden esta brecha en 45 “celdas” de educación-experiencia (por ejemplo, una de estas celdas contiene personas con 19-23 años de edad y 6-8 años de educación). Dentro de cada una de estas celdas, los trabajadores tienen las mismas características tangibles básicas. La línea azul es la mediana de la brecha entre los países a través de las 45 celdas; la línea verde es el mínimo, la línea roja es el máximo.

Previamente, el economista Gordon Hanson también encontró poca evidencia a favor de la convergencia de salarios durante la primera década de NAFTA. Ahora, dos décadas desde su instauración, esta situación no ha cambiado.

¿Por qué no? Nadie está seguro pues muchos otros eventos han ocurrido en el mismo período de tiempo-la crisis del Tequila, dos recesiones en EE.UU y la guerra contra el narcotráfico. Más aún, la situación podría cambiar a medida que los años transcurren. Pero estos estudios contienen tres mensajes principales:

- Primero, sí existió convergencia dentro de las celdas de educación-experiencia que registraron los mayores flujos de trabajadores de un país al otro—pese a las leyes restrictivas de migración. NAFTA ejemplifica lo que Lant Pritchett denomina “todo-menos-globalización laboral”: se esperó que la convergencia salarial surja a partir de la liberalización del comercio y la inversión, pero no de la migración. Esto no ha sido suficiente. Pero la migración podría ser suficiente para generar cierto grado de convergencia. El mercado laboral puede lograr ciertos objetivos que el mercado de bienes y de capital no.

- Segundo, el estudio muestra que niveles irrealmente altos de migración serían insuficientes para lograr una convergencia total de salarios. Sin importar el grado de libertad en el comercio, inversión o migración, existirían límites sobre el grado de convergencia en estándares de vida entre países que estos podrían causar. Algún factor fundamental e inamovible estaría produciendo esta brecha en la frontera. Daron Acemoglu y Jim Robinson ilustran este fenómeno mediante diferencias sustantivas en estándares de vida en diferentes partes de Nogales, una ciudad dividida en dos partes por la frontera entre EE.UU y México. Los autores argumentan que el factor inamovible que sostiene la brecha salarial en la frontera es, principalmente, la diferencia en las instituciones económicas y políticas en cada lado.

- Tercero, estudios como este no ilustran todas las maneras por las cuales los salarios podrían converger. Tales estudios comparan a personas contenidas en las celdas de educación-experiencia en cada lado de la frontera, lo cual es útil. Pero estos no están diseñados para capturar la convergencia entre estándares de vida que surge cuando hay menos gente en celdas de bajos salarios. Por ejemplo, considere la celda de personas entre 19-23 años de edad con 6-8 años de educación en México. Esta celda se podría reducir en tamaño de tres maneras: un cambio demográfico podría significar una menor cantidad de personas entre 19-23 años de edad, lo cual está ocurriendo a medida que las tasas de fertilidad en México continúan cayendo. La expansión de la educación podría significar menos gente que abandona la escuela con 8 años o menos, lo cual está ocurriendo en México también. Finalmente, las personas en esta celda pueden salir de México, de manera que la mayoría de la brecha salarial respecto a sus contrapartes en EE.UU desaparecerían rápidamente. El salario promedio de un mexicano cualquiera podría aumentar incluso si los salarios dentro de una celda no están cambiando, siempre y cuando las personas transiten de celdas de bajos salarios en México a celdas de salarios más altos dentro o fuera de México.

La lección aprendida es que el concepto de “todo-menos-globalización laboral” ha sido insuficiente para promover la convergencia salarial entre EE.UU y México para trabajadores equivalentes. Además, la implementación de “todo-incluyendo-globalización laboral” podría producir cierto grado de convergencia, pero aun así estaría lejos de una convergencia total. Una convergencia total requeriría una reforma institucional, una de las áreas más emocionantes e importantes en investigaciones recientes. Si deseas una introducción al tema, dale un vistazo a Acemoglu y Robinson, Avner Greif o Douglas North.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.