Recommended

How can we help teachers to upgrade their pedagogical skills? Teacher coaching is a promising and increasingly popular candidate. Teacher coaching means teachers receive feedback in their place of work on specific things they can do better, not some general theory of pedagogy that’s completely disconnected from their day-to-day practice. A meta-analysis of 60 studies in high-income countries found big impacts on both teacher practices and student learning. In South Africa, a comparison of teacher coaching with traditional teacher professional development (think: all the teachers go to a centralized location and receive instruction) showed that student learning impacts were twice as large for teachers who received coaching. In Peru, teacher coaching improved teachers’ pedagogical skills and student learning outcomes.

But bringing coaching programs to scale effectively has proven challenging even in high-income countries, with large programs only about one-third as effective in raising student learning as small programs. One oft-proposed way to bring coaching to scale is by doing it virtually. That way, systems can identify a few, excellent coaches who can reach more schools. Indeed, comparisons of virtual coaching programs and in-person coaching programs in high-income settings don’t suggest large differences (although the number of studies is few enough that one should take those results with a grain of salt).

A study published last year reported on a randomized controlled trial comparing virtual to in-person teacher coaching in government-run primary schools in South Africa. (I blogged about it!) Teachers with virtual coaches communicated with those coaches via messaging and phone calls. They received tablets with teaching materials and tips loaded up. They were encouraged to share videos of themselves in a group with the coach and other teachers. In-person coaches observed lessons and provided direct feedback. After a year, English listening comprehension rose in both groups relative to a control group. Virtual coaching and in-person coaching both improved student performance by roughly equal amounts. Exciting news for virtual coaching!

But wait, a new study follows up those students after three years, and the results are not so promising. In “Can Virtual Replace In-person Coaching? Experimental Evidence on Teacher Professional Development and Student Learning in South Africa” (by Cilliers et al., including CGD non-resident fellow Nompumelelo Mohohlwane), researchers show that after three years, students of teachers with virtual coaching still had gains in their English listening comprehension, but the gains for students of teachers with in-person coaching were about 2.5 times as high. Furthermore, the in-person coaching group also showed gains in English reading proficiency; the virtual coaching group did not. So virtual coaching worked for simpler skills (listening comprehension), but less so for more complicated skills (reading proficiency). The virtual coaching group actually performed worse than the control group in one area: home language literacy.

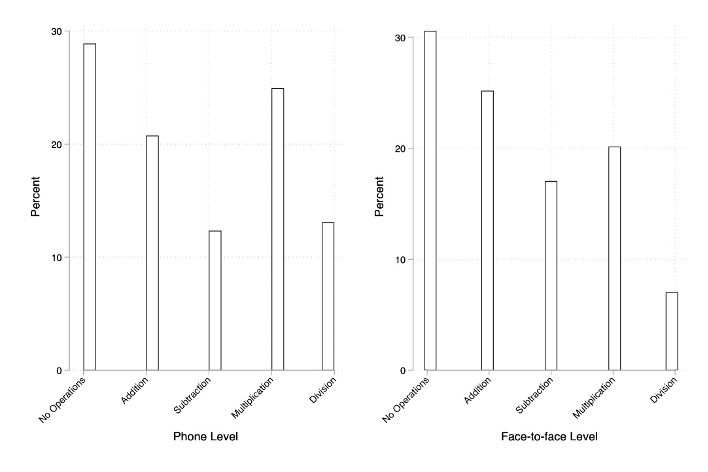

Both teachers who participated in virtual coaching and those that received in-person coaching drew on a wider range of pedagogical activities (including having the students do writing exercises or working individually with students), but only teachers who received in-person coaching increased their use of certain activities, like having pupils read individually or group-guided reading. Over time, teachers receiving the virtual coaching arm used the tablets assigned to them less and less, except in the week when student assessments were due (see the figure below). The follow-up data shows that few teachers consistently submitted videos of themselves to their coaches. The poorer performance in the virtual coaching group for home language literacy was likely driven by teachers in that group dedicating less time to home language instruction. The teachers with on-site coaching also spent less time on home language instruction than control teachers, but the reduction was smaller.

How many slides did the teachers receiving virtual coaching access in their tablets, week by week?

Source: Cilliers et al. 2020

The costs were roughly comparable across the two interventions. (Virtual coaching was a little cheaper.) Even though virtual coaching required fewer coaches and less transport, it required a much larger technology investment. Tablet costs (including maintenance) were nearly nine times as much as providing printed lesson plans. Because of the larger learning gains, on-site coaching proved more cost-effective.

A challenge with virtual coaching in this case may include that teachers neither built the trust nor felt the accountability with virtual coaches that can be engendered in face-to-face encounters. Teachers with face-to-face coaches likely received clearer feedback on fundamental skills (like time use), that it would be hard for a virtual coach to observe.

The authors offer suggestions on how to make virtual coaching more effective, such as introducing initial face-to-face coaching to establish a stronger relationship and mandating regular sharing of self-made videos for the coach to give feedback. But these changes shrink potential cost gains from virtual coaching, making the value of the trade-off less obvious.

Teacher coaching is still promising, but these findings should temper the hope that education systems can do it on the cheap or that tablets will solve problems like a magic wand. That’s consistent with the study in Kenya that found that distributing tablets boosted literacy, but it did not boost literacy any higher than a non-technological alternative.

These studies also point to the importance of gathering longer-term data, both during the intervention for interventions that endure for multiple years (like this one) and after the interventions end. Out of one sample of 77 randomized controlled trials of school-based interventions in low- and middle-income countries, only two gathered data more than a year after the intervention ended. This new study out of South Africa shows that the results after the first year may be poor predictors of how educational investments will play out over time: In this case, the short-run impacts.

Ultimately, few teacher policies will be effective without buy-in from teachers. Education technology interventions will only be effective if teachers use them (as we’ve seen in Colombia and elsewhere), and in this case, it seems like teachers used the technology less and less over time. The problem was not—as the figure above shows—that teachers couldn’t access the technology. They just engaged it less and less. Technology interventions need to think about how to engage teachers effectively if they hope to improve education systems.

This post benefitted from feedback provided by the authors of the study. Any persistent errors are, of course, my own.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.

Image credit for social media/web: Cilliers et al 2020